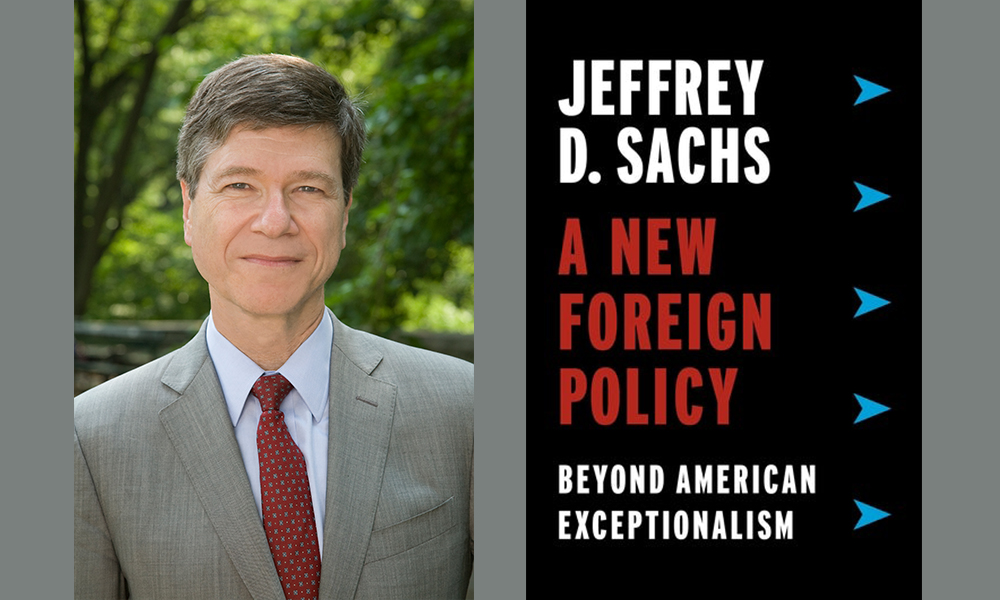

How might a sustainable-development approach to our domestic politics help foster sustainable-development goals in a global context? How might American-exceptionalist thinking get in the way of both projects? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Jeffrey D. Sachs. This present conversation focuses on Sachs’s A New Foreign Policy: Beyond American Exceptionalism. Sachs is a world-renowned leader in sustainable development, widely recognized for his bold and effective strategies to address complex challenges such as debt crises, hyperinflation, the transition from central planning to a market economy, disease control, the escape from extreme poverty, and the battle against human-induced climate change. Sachs’s books and edited collections include The End of Poverty (2005), Common Wealth: Economics for a Crowded Planet (2008), The Price of Civilization (2011), The Age of Sustainable Development (2015), and Building the New American Economy: Smart, Fair & Sustainable (2017). Sachs directs the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University, where he is a University Professor. He directs the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network, and is a commissioner of the UN Broadband Commission for Development. He has been an advisor to three United Nations Secretaries-General: Kofi Annan, Ban Ki-moon, and Antonio Guterres. In 2015, Sachs was named co-recipient of the prestigious Blue Planet Prize for environmental leadership. Time magazine has named Sachs among its one hundred most influential world leaders. The New York Times has called Sachs “probably the most important economist in the world,” and a survey by The Economist has ranked Sachs among the three most influential living economists.

¤

ANDY FITCH: A New Foreign Policy takes the sustainable-development framework (prioritizing smart-infrastructure investments, significantly expanded renewable-energy production, more equitable income distribution, tech-fostering education) that you have outlined for various domestic contexts, and applies this to a broader international arena. Could you introduce that sustainable-development approach here by sketching how its basic principles might overlap whether one adopts a domestic- or global-policy vantage — and also by pointing to where this new book might need to provide a slightly different emphasis, argument, agenda? Specifically picking up this book’s subtitle, could you start to sketch how the follies of American-exceptionalist approaches (both at present, and amid a longer arc of US history) might contribute both to the necessity and to the difficulty of adopting this sustainable-development model as a guiding frame for today’s foreign policy?

JEFFREY D. SACHS: Sustainable development applies to each individual country, and also applies globally. In our economic, social, and political life, it aims for prosperous, fair, and environmentally minded societies. Within a United Nations context, most of the world already has accepted these basic principles — dating back to the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, and then with the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015, and the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015. Of course we haven’t yet fulfilled those goals within our own country, much less globally. So this book (and my writing more generally in recent years) emphasizes the danger we have put ourselves in by not heading in a more sustainable direction. In fact, we seem to have displayed a collective tendency to head away from these goals, towards increased inequality and self-destructive habits ruining the planet.

In the international context, a US foreign policy which keeps drifting further and further from cooperation only has aggravated these negative and quite frightening outcomes. And of course the US by itself cannot control the US climate. The US by itself cannot ensure global biodiversity, or even biodiversity in its own territory. The US cannot secure the safety of the planet, but it does need to participate in that shared effort.

If we don’t increase global cooperation significantly, not only will the world become much more dangerous, but the United States itself will become a much less happy, much less successful, much more unstable place. The storms, the heat waves, the emerging diseases will not stop at our national border. So we need to foster sustainable development in a foreign-policy as well as a domestic-policy context. And with Trump, our domestic and foreign policy have become just bizarre, and certainly antithetical to any sustainable approach. US foreign policy always has had a powerful exceptionalist streak (not just taking pride in the distinctive nature of our American story, but in a much more practical sense believing that the rules don’t quite apply to us), though now that all seems even more extreme.

Here my book suggests that this sense of America’s exceptional purpose has, from the start, led to such brutality on our own continent. Then since we became the world’s most powerful country (following the second World War, and our actions then), this exceptionalism has complemented (strangely enough) our multilateralism. You can see that in the unending-seeming stream of wars, in the unending decisions to ignore international agreements, in the consistent refusal to sign global treaties, and in this more general sense that these rules and regulatory bodies just don’t apply when it comes to the United States.

Today, this basic tension between our exceptionalism and our multilateralism looks more obvious than ever. Our leaders claim that joining treaties could only weaken our will, and deny our prerogatives. Today we actually have ended up with the most anti-multilateralist government in US history, and certainly in our history as a leading power. As a foreign-policy matter, not only does the Trump administration oppose this idea of multilateralism — it actually seems to consider the very idea of sustainable development somehow bad for us. The Trump agenda does not concern itself with social inclusion, economic justice, or environmental sustainability. That puts us, I believe, at profound risk.

Just to linger for a second on this foundational-seeming contradiction between exceptionalism and multilateralism: when could and should we parse something like a quantitative / competitive American exceptionalism (we have the most profitable companies, the strongest military) from a qualitative / categorical American exceptionalism (our political project remains unique, morally grounded in ways no other nation can claim)? And let’s say we acknowledge that this latter drive towards qualitative exceptionalism always has had delusional aspects (prompting powerful sectors of US society to overlook the basic hypocrisies of our self-declared democratic republic conducting genocidal campaigns against Native Americans, enslaving Africans, reinforcing racist patriarchy throughout most of our existence, aggressively pursuing colonial and then Cold War dominance throughout the 20th century). Nonetheless, when should we still parse a qualitative American exceptionalism that prioritizes exemplary global leadership from an isolationist or unitary or hegemonic exceptionalism? Given your own ongoing identification with the aspirational appeals by which FDR and JFK inspired so many Americans, for example, where might you still find room for a perhaps more nuanced exceptionalist rhetoric — or which historical developments convinced you to abandon for good even that more high-minded exceptionalism?

I’m all for high-mindedness, but not a high-mindedness that depends on one indispensable country. I consider the view that “Only the US can get it done” both wrong and dangerous. And as Reinhold Niebuhr said, this belief in American omniscience and omnipotence leads to a kind of arrogance that is not just factually false, but behaviorally dangerous — because it constantly reinforces the tendency to demand that everything go your own way.

We saw this even in some of President Obama’s finest moments. For example, when signing the Paris Climate Agreement, President Obama made statements suggesting that US leadership had made this agreement possible. In fact, the US only had contributed its own foot-dragging for the entire period from 1992 to 2015. For 23 years, we did nothing to implement the existing environmental frameworks and conventions. Then, in 2015, we finally pledged to follow up on what we first had signed and ratified in 1992. And America recast this as an exceptional contribution. But many dozens of countries had long ago moved way ahead of the US in their commitments, in their forward-thinking policies. Maybe the US helped to bring some of the stragglers along, though not very many — because even most of them already had pushed far ahead of the US.

And of course the US also has done many good things, but again sometimes without much self-awareness. When the Ebola epidemic first broke out in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, a long period of inaction set in. Then finally the US government stepped up and provided help. That assistance no doubt contributed to bringing this epidemic under control, though this whole effort ended up taking much longer than it should have. We lost many lives along the way. And I know (from traveling to those countries for years beforehand, and trying to get the US and others to do much more in disease prevention, in disease surveillance, and in supporting community-health workers) how meager our response had been for such a long time. Well, in the end, President Obama did say: “We need to stop this Ebola epidemic.” Okay (and of course we also relied on many other countries’ contributions). But to me the real story came from how we had left those West African countries in a place of extreme vulnerability and duress for so long.

Then once we saw no new infections, the whole broader ongoing problem again just dropped out of sight and out of mind. Rather than asking: “How can we now proactively build up the health systems in the poorest countries?” we just moved on. We certainly never made it to thinking about these countries for their own sake. We just stopped the epidemic’s spread in the short term, then dropped it — and again always while boasting about all the great things we did, and how America had saved the day. We then continued to neglect to think about how extreme poverty, and inadequate or entirely absent healthcare systems, and a lack of health workers, could lead to future disasters. And again, all of that happened even within the Obama administration’s foreign policy, and even with very positive outcomes.

Of course during the Obama administration we also had the folly of the war in Syria, which I consider a US-led war of regime change, definitely with the CIA empowered and instructed to overthrow the Syrian government. We had a similar regime-change operation in Libya, and so on. So even under our most multilateralist president in recent times, we saw disturbing examples of American exceptionalism. Even with a president who I certainly supported, and who in many ways did a very fine job, we saw this tendency to ignore international law — in fact to violate international law, to overthrow governments. This happens in both of our major political parties, from one administration to the next. And this leads, in my reading, to consistent failure.

Today this whole approach that we’ve pursued since 1945, and especially since 1947, plays out in vulgar ways, for example with our current Cold War-like operation in Venezuela. Thank goodness the US so far has not (and hopefully never will) put troops on the ground. But we already see an overt attempt, with a lot of behind-the-scenes efforts, to overthrow a foreign government, again justified in this exceptionalist (and, in my view, illegal) manner — and with much of the mainstream media not doing much to counter that narrative.

Returning then to your book, and to the global stakes it sketches, could we consider what A New Foreign Policy describes as “the world’s biggest geopolitical trend today,” the economic integration of the Eurasian landmass, principally through increased exchange and coordination among EU countries and China? How might an oblivious American exceptionalism diminish our capacities to recognize and respond to such trends in the first place? Or how might exceptionalist approaches push us towards zero-sum thinking, and defensive posturing, before an increasingly multipolar world: preventing us from sharing in wide-ranging potential for accelerated technological advance, enhanced ecological sustainability, unprecedented peace — particularly as various regions and individual nations converge in terms of their relative strength?

At the core of this contemporary exceptionalist approach, you see these efforts to replay the Cold War, this time focusing on China instead of the Soviet Union. The Cold War itself would need a long and complicated analysis I won’t go into here. But in my view, though the Soviet Union had many horrible aspects, we still fundamentally misunderstood it. And so we participated in a massively exaggerated nuclear-arms race that nearly destroyed the world on several occasions — again thanks directly to our exceptionalist mindset. We weren’t the only bad actor, to be sure. But our American mindset too often means treating the other side as an implacable enemy, and demanding US supremacy, and interpreting any move made by this other side (however defensive in nature) as an offensive provocation requiring a swift response, and justifying our break from international norms and regulations.

Today, we (at least our hardliners) have placed China in this role of existential enemy. China’s size (four times larger than the US population, though with per-capita income still roughly at one-third of US levels, or one-sixth when measured according to international market prices) absolutely runs against the core of exceptionalist thinking. If I could paraphrase what I sense in the minds of certain American strategists: How dare they? Who the heck do they think they are, trying to equal the stature of the United States? Of course, as I just noted, the Chinese remain much poorer than us, and it doesn’t seem so especially arrogant or surprising that they would like to have a normal life, thank you — a life that offers the benefits of technology and of a prosperity not so different from our own.

But in the minds of people like presidential advisor Peter Navarro, and the diplomat Robert Blackwill, we have to contain this aggressive China. We have to stop their rise, and keep them from surpassing us numerically. Well, that does seem pretty tough, because it would mean forcing them back (permanently) to a position of less than one-fourth our own per-capita prosperity. But you can see playing out before our eyes right now this broader shift of mindset, politics, terminology — all to make China an enemy, when just a few years ago US punditry and official rhetoric tended to frame China basically as a large trading partner of the United States.

Nothing has changed between then and now to merit this kind of response. And I found it fascinating recently that when Trump seemed to move closer towards signing a trade agreement with China, Chuck Schumer wrote to him basically saying: “Don’t get soft now.” Again that just shows how this exceptionalist foolishness plays out beyond any partisan politics. And of course Trump’s own version includes an extra dose of protectionism. But neither side has shown much interest in establishing a normal, reasonable, fair-minded relationship. Both sides seem to be sliding in the opposite direction.

Sure in terms of US relations with particular countries, A New Foreign Policy traces classic security-dilemma dynamics shaping present-day US standoffs both with China and with Russia. You persuasively point to basic hypocrisies of a US that violated its late-20th-century pledge to limit NATO expansion now castigating Russia as the sole destabilizer in Eastern Europe, or of a US maintaining hundreds of military bases worldwide overreacting to China’s establishment of a single such base in Djibouti. But you also argue that, even as we should pursue constructive international cooperation, we never should adopt a naive or unconditional commitment, always retaining the option to resort to more “realist” calculations when circumstances demand. So when does accommodating a potential adversary’s bad behavior itself become unsustainable? Specifically for Russia, when does its understandably defensive response to NATO encroachment push back too far by violating its neighbors’ sovereignty and eventually compromising our own democratic process? Or for China, when you call on us to abandon a negative-sum economic outlook, when does the double-punch of American firms facing forced technology-transfer plus subsidized state-owned competitors produce its own negative-sum scenario that must be directly opposed?

The first rule of engagement comes from Jesus: we shouldn’t point out the mote in the other’s eye without recognizing the beam in our own. If we deal with counterparts honestly and transparently, calling out our own sins along with theirs, we’ll get a lot farther. But we’ve tended only to see the wrong in our counterparts. This leads to no end of posturing, finger-pointing, and escalating conflicts.

The second rule of engagement focuses on honest appraisal. Consider what the 1950 National Security Council policy paper NSC 68, which set the terms for the Cold War, claimed about the Soviet Union: “The design [of the Soviet Union], therefore, calls for the complete subversion or forcible destruction of the machinery of government and structure of society in the countries of the non-Soviet world and their replacement by an apparatus and structure subservient to and controlled from the Kremlin.” This works well as heated rhetoric for a political potboiler, but it offered utter nonsense in practice, and contributed markedly to the ensuing nuclear-arms race. Recently though we’ve returned to that rhetoric, claiming in the 2018 National Security Strategy: “China and Russia want to shape a world antithetical to U.S. values and interests.” Antithetical, really? And how easily the pundits again fall into place, calling China an enemy and so forth.

Could we also consider, by contrast, the significant role that regional cooperation plays in your own sustainable vision, particularly on crucial questions regarding renewable-energy distribution, fresh-water access, disease vectors, violence prevention? You point, in fact, to the specific example of longstanding political tensions among China, Japan, and South Korea obscuring their dramatically accelerating economic integration — with an exceptionalist / oblivious US increasingly squeezed out of this region soon to emerge as a “world-leading technological colossus.” Again, rather than responding to such developments with either isolationist or belligerent exceptionalism, could you describe how and why the US should welcome such regional integration around the world, and should itself participate actively on a hemispheric or transatlantic or transpacific scale?

Absolutely. And I would start not just from some mere US obliviousness, but from an active US desire to keep South Korea and Japan on our side against China. Those countries have their own reasons to watch China warily. Having such a huge neighbor definitely offers its own complications, as does the last two thousand years of interactions among these cultures. South Korea and Japan worry about their own sovereignty, their own future, but they also do want to cooperate. And in my opinion, the increasing economic integration among these countries does show one way towards a new type of cooperation the whole world needs. And yet, alongside all of that, you again see this self-serving US exceptionalism, this effort not to let Japan and Korea cooperate too much with China, this desire basically to keep China contained — with the US opposing all Chinese regional initiatives, especially the Belt and Road.

The Belt and Road Initiative, broadly speaking, amounts to a very sensible, very useful plan first to integrate China and its nearest neighbors, but then ultimately to design an integrated infrastructure for the entire Eurasian landmass. We absolutely need this done in a sustainable way. A poorly designed project of this scale could tilt the planet in an irrevocably hazardous direction. But if designed well, if implemented smartly, and if in fact promoting peace, the BRI ultimately could become the largest single sustainable-development infrastructure project in our planet’s history.

But the US sounds just dead-set against that outcome right now. We keep warning other countries: “Don’t join. Don’t cooperate with China. You’re getting suckered. Don’t fall into this trap.” Of course that hasn’t succeeded in most cases, because many countries see the need and the benefit for this kind of infrastructure integration. When Italy recently joined the Belt and Road Initiative, they received a harsh response from the United States. Here again we’ve resorted to our Cold War mentality. Rather than recognizing the global benefits of such a project, and figuring out how to make American companies a part of it, and helping to figure out how the BRI can assist the world in implementing the Paris Climate Agreement and Sustainable Development Goals, we’ve adopted an antithetical position, apparently because we can’t even imagine how that kind of cooperation could happen. Instead, we seem stuck in a classic leading-power divide-and-conquer mindset. We actually want to reinforce these divisions in every region: say India versus Pakistan, or China versus South Korea and Japan, or Saudi Arabia versus Iran. We (or some of our leaders) actually seek to play up these divisions, rather than promoting the kinds of regional integration that might get some allies to say: “Well, thanks for offering your input, but we don’t really need you so much anymore anyway.”

And here specifically in terms of making such regionally integrated growth sustainable, could we also consider the lamentable dynamics by which praiseworthy economic gains in the developing world over the past 30 years have at the same time contributed significantly to environmental degradation and to global climate change? In the past, for instance, I’ve seen you present regulated capitalist enterprise as the most dramatic driver of individual well-being that humanity ever has devised. So today, given the sustainable-development model you pursue, how might you simultaneously address demands from an eco-conscious left that we fight rapacious capitalism as a whole (whether private markets or state capitalism), and dismissals from the right that advocates for redistribution just cannot grasp how real-life economic growth happens in the first place?

The solution to this dilemma is a kind of Aristotelian golden mean between an all-powerful state and an all-powerful market. Both extremes are disasters. A mixed economy, in which private business operates alongside (and ultimately under the control of) national politics, offers the right balance. Today you find the best exemplars of this arrangement in Northern Europe: the Scandinavian economies (Denmark, Norway, Sweden), the other Nordics (Finland, Iceland), and Germany and the Netherlands. While all economies have major structural challenges, while all societies constantly must battle against greed, cheating, and corruption, these Northern European countries have succeeded at sustaining true regulation of business together with a vibrant private economy. They exemplify the social-democratic model that I espouse, known in Germany as the social market economy. Alas, in the United States, the concept (and even the notion) of social democracy remains little known. I’m hoping against hope that Bernie Sanders can usher in a new social-democratic ethos and politics in the US.

Given that social-democratic perspective (as well as your search for an Aristotelian golden mean), could you also address how and why your new foreign policy would incorporate a doctrine of subsidiarity, solving problems of sustainability at “the lowest feasible level of governance”? Could you sketch how such a principle might play out, say, in terms of localized toxicities, regional pollution, global climate change? And could you describe how subsidiarity might manifest specifically in a forthcoming century that is not a “Chinese century” or an “Indian century,” but a “world century”?

Subsidiarity means addressing problems at the most local level possible. Consider climate change. To succeed, we need to end greenhouse-gas emissions. Individuals need to change personal behaviors (walking rather than driving, eating more plant proteins in place of beef). Communities need to recycle and close down methane-emitting waste dumps. Cities need to introduce charging points for battery-powered electric vehicles, and to implement building codes for zero-emission construction. States need Renewable Portfolio Standards to push their utilities towards zero-carbon energy. National governments need to invest in transmission grids to tap high-quality renewable energy. Regional groups (such as the European Union, the African Union, ASEAN, and others) need to coordinate trans-boundary infrastructure. And globally, we need the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Paris Climate Agreement, and the World Trade Organization, among other regimes and institutions, to create a more rigorous framework for global diplomacy — so that individual countries don’t shirk their responsibilities. The essence of this challenge, and of many other challenges in sustainable development, is to find the most appropriate solutions at multiple scales and levels of political organization.

Returning then to your deft triangulations of classic “right” and “left” rhetoric, does it ever make sense for globally minded institutionalists to call for something like “sustainable competition” among the world’s regions (further binding us to our neighbors, at the very least), rather than appealing more broadly to “international cooperation”? Or where might regional competition defang some of nationalism’s more destructive aspects, while also disarming skeptics of global approaches (and while somehow evading ethno-chauvinist fault lines)? Or when should we welcome, for instance, East Asian industrial / distribution models surpassing our own capacities to provide affordable electric cars to developing-world consumers, even as our own firms strive to pioneer next-generation engineering efficiencies?

In general, we should welcome a race to the top — to bring new technologies to market, new business models that honor sustainable development, lower production costs for goods and services (again as long as these outcomes still uphold our environmental, social, and labor standards). Competition within reason is fine. Again, I’ll turn to Aristotle: complete competition is ruinous, and complete cooperation is hopelessly naive. We need to find a middle path, especially one where both our competition and our cooperation get strategically directed to our ultimate goals.

Here still in terms of finding the right competition / cooperation vector for a given diplomatic context, and here pivoting back to how a narcissistic American exceptionalism might prevent us from making truly world-historical contributions to enhanced peace and prosperity, I found the account of your personal engagements with Poland and the Soviet Union at the Cold War’s end especially poignant. Could you sketch the long-term potential you saw then for the US to extend the type of stabilizing assistance provided to Poland to a reform-minded Soviet Union or its Russian successor — and the bipartisan failings of the US to prove its exceptionality in that missed moment?

That’s right. I’ve described many times how the US and IMF help that I successfully advocated for Poland (including debt relief, debt cancellation, a currency-stabilization fund, emergency funds, and the like) was bluntly denied for the Soviet Union in the last year of Gorbachev’s rule, and for an independent Russia in the first years of Yeltsin’s presidency. Gorbachev was intent on democratizing the Soviet Union, and sought Western financial help to pull this off. Yeltsin aimed to make Russia a “normal” democratic country, as hard as that would have been. In both cases, the US said “Nyet!” The White House (and no doubt much of the country) viewed Russia as an enemy, not as an aspirant to normalcy. And worse, the neocons remained intent on “winning” the Cold War, not just ending it. In retrospect that all does stand out as a truly historic, sadly squandered opportunity.

And still on this topic of constructive opportunities, one other forecasted regional dynamic I found especially interesting in your book involves the African continent seeing the biggest population increase (by far) over the next century, taking on a socio-economic significance for global trends more like China’s demographic footprint does today. How should the US most proactively cultivate our relationship with this (obviously quite expansive and diverse) region of the world as these trends start manifesting?

Africa’s future is still highly uncertain. It could enjoy a dramatic growth in educational attainment and job skills, and set the path to eliminating extreme poverty. Or it could get caught in a downward spiral of poverty, instability, and environmental stress — with its population soaring to more than four billion people by 2100. Obviously, Africa’s own well-being and our global well-being depend very much on achieving that first trajectory. The most important single step would involve ensuring that every child in Africa can complete at least a secondary education. Yet to accomplish this, Africa will need significant financial help. Once upon a time, such help would have come willingly and even eagerly from the US. Now the US is cutting aid in a fit of ignorance and petulance. Again I find it profoundly sad that Washington has abandoned the language of international decency and partnership. I can only hope that Europe, China, and others will fill the massive gap in financing left by the US government’s neglect and disdain.

Your book likewise laments an insular, self-deluding, exceptionalist approach that has taken hold of the American electorate, precisely when ecological disaster and escalating social disparities make the need for global cooperation greater than ever — and, simultaneously, when the world’s constructive efforts to combat global scourges (such as AIDS, malaria, TB), and to pursue sustainable development (say in Agenda 2030 objectives, and Paris Climate Accord pledges), never have been stronger. Could we pause on the Paris Accord, and could you describe what its long-term implications look like today, particularly from a less America-centric perspective? To what extent, for example, do doubts among a demoralized eco-minded constituency in the US (as almost every nation so far fails to meet its Paris targets, and as scientists’ projections increasingly suggest these targets themselves will be nowhere near sufficient) say more about our guilty gloomy position from the sidelines? Or to what extent does that skepticism reflect your own concerns even as an ecologically minded institutionalist advocating for sustainable growth?

Most of the world is keen to save the planet from human-induced climate change. The few outliers are the fossil-fuel lobbies in the main producing countries, including the US, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Australia. China and India are on the borderline: each ready to do far more, but also demanding more action by the US and other rich countries, and feeling pressure from their own large domestic coal industries.

Most Americans want action. Most US states have started taking action. The problems primarily come from our federal government (where the oil lobby still holds sway), and from a few states with significant fossil-fuel production. In other words, we can win this battle — indeed we likely will win this battle at some point soon. But first we need to face down not society-wide obstacles or denial, so much as individualized and localized challenges posed by greed, corruption, and short-sighted self-interest.

To close then, I appreciate the brevity by which A New Foreign Policy dispenses with basic contradictions in Donald Trump’s worldview (by outlining, for instance, why bringing back industrial production to an automation-infused US economy doesn’t create many jobs; or why recent corporate tax cuts won’t make the US more competitive in the long term, so much as they will accelerate an international race to the bottom; or why the penny-wise pound-foolish gutting of international aid generates much more destructive and expensive militarized outcomes). So rather than dwell much on Trump’s ill-timed “exceptionalist foreign policy in a post-exceptionalist era,” could we address the extent to which Trump’s inept approach symptomizes a few broader failings of foreign-policy imagination (among populists, conservatives, Republicans, perhaps both parties) which a post-Trump US will quickly need to correct? And could you articulate the governing spirit and logic behind your concluding “10 priorities for a New American Foreign Policy,” and why these particular policies would prove most effective at “achieving true national security and well-being for the American people”?

Though Trump is clearly the worst president (with the possible exception of James Buchanan) in American history, the problems with US foreign policy definitely transcend Trump. I do consider that this book’s main point — to trace the longstanding patterns of and problems with American exceptionalism: the belief in providential support for our endless wars against Native Americans, for our 20th-century imperialism, for our 21st-century wars of choice. With America’s remarkable power in the 20th century’s second half, this claim to exceptionalism seemed obvious and proved. American hubris grew, giving us Vietnam, the Contra Wars, the Iraq War, and military bases in more than 70 countries and territories around the world. Along the way, certain Americans claimed the Cold War’s end as yet another triumph of American exceptionalism (not as the massive failure of the Soviet model).

Today, however, the global spread of technology and economic growth (most notably to China, but not only to China) means that we must revisit these past assumptions. If the neocons hold sway, they once again will claim that a new arms buildup, and perhaps some wars (for instance with Iran), will do the job of restoring US preeminence. But if better-informed and more balanced minds prevail, then we gradually can move to a cooperative world of dispersed power. The US would remain very powerful, indeed invulnerable to attack from outside — but one of several major powers in a world guided by common rules and shared objectives, rather than by US dominance. Here most of my 10 points in fact focus on us getting along with the rest of the world: living within the UN Charter, and addressing common challenges such as climate change.

The 10th recommendation, however, calls on us to celebrate one area of true American exceptionalism, the current in American history that champions diversity in all its forms: racial, ethnic, linguistic, in terms of religion, in terms of sexual orientation, and other important aspects of our lives. Here America still has something important to say to a diverse world, about the beauty and strength and grace in a society of so many histories and cultures.

So our dyspeptic president might rail against precisely that which had made America decent. But of course American history long has been a battle between exclusion and diversity. That battle continues today. And we only can secure our strength as a nation by cherishing that diversity, by promoting our historical, cultural, and familial connections with the entire world.