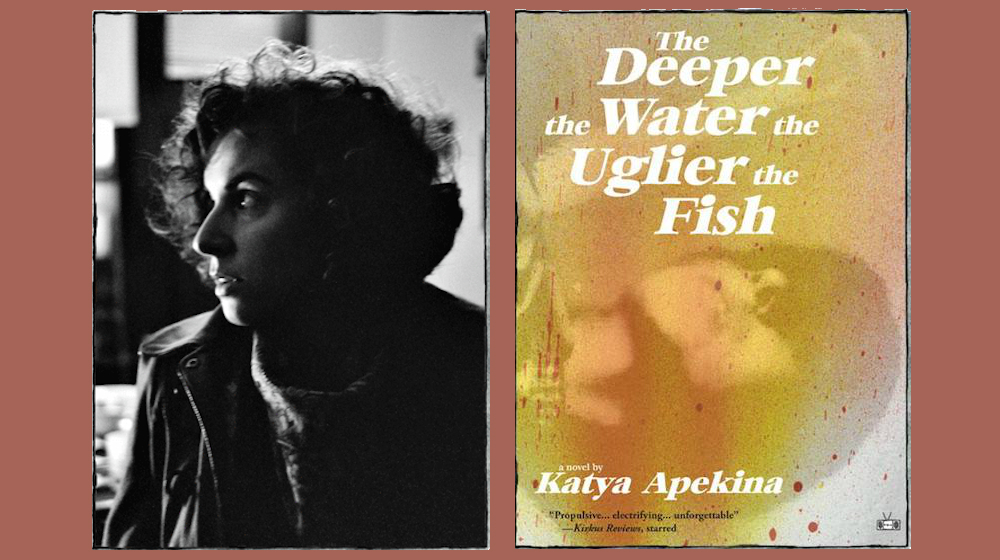

Katya Apekina’s debut novel, The Deeper the Water the Uglier the Fish, is a story about two sisters coming to terms with their mother’s attempted suicide, and the pleasures and violations of being proximal to an artist. Shuttled to their father’s New York City apartment when their mother, who was a poet and muse to their father, is checked into the hospital, Edie and Mae experience the strange repercussions of living with artists ensconced in their work. “I feel like she is reaching […] into my brain and squeezing my thoughts,” teenage Edie thinks of her mother at one point, “checking each of them for ripeness.”

Apekina’s prose has a similar effect. This is a thought-squeezing novel, a cacophonous page-turner with more surprises than I can list. It was my pleasure to interview Apekina about her work and this novel, which surely heralds a must-watch career.

¤

JOANNA NOVAK: The Deeper the Water the Uglier the Fish is family drama, historical excavation, ghost story, treatise on the parent/child relationship, portrait of mental illness, and Künstlerroman all in one — something I greatly admired about the novel. How did you conceive of the book’s genre, in a loose sense, originally, and how did that conception change as you wrote the book?

KATYA APEKINA: Years earlier I had been hired to do research for a nonfiction book about white southerners who joined the Civil Rights movement in the ’50s and ’60s. The book was killed, but this sort of rose out of the ashes. The content from my research became the backstory. I had originally thought I would try writing historical fiction, but aside from that being sort of outside the scope of my interest and abilities, I actually became more excited thinking about looking at the effects generationally.

Also, during the research I had been reading lots of oral histories, and going through documents in archives and that inspired the form. I was interested in how truth is multifaceted and contradictory and I think the form lends itself well to exploring that.

How long did you spend drafting the novel? What most surprised you about the writing process? How did the book change in revision?

The book took me about five years to write. About one or two years after I started the book, I went to an art residency and felt like I was hitting a wall. Originally, the character of the mother had died at the beginning, and the book ended up being about grief. The grief overwhelmed the novel, it wasn’t really the book I wanted to write or the thing I most wanted to explore, and it consumed everything else. So, I brought the mom back to life, put her in a mental hospital, and started over. It was hard to start over, after I had already spent so much time going down one road, but I think doing it at an art residency where I was fully “in it” really helped. I guess it took me three years to have a complete draft that I felt good enough about to show people. During that time I also had a baby, and luckily I got an Elizabeth George Grant which helped pay for childcare while I finished. I thought, I need to finish before I have a baby, but I didn’t, and it ended up being fine. I was super sick during my pregnancy and couldn’t write much, but after I had my daughter I basically wrote the whole last section. I wasn’t letting myself write the end until the rest of it was in order and complete, because I didn’t want to send it out before it was ready, and I didn’t trust myself to wait. I knew I wouldn’t be able to send it out if it was missing an ending, so until everything leading up to the ending was polished, I didn’t write it. There was a strong impulse to get outside validation and opinions, and I knew that it would be bad for the book to get that too early (with exception of a few very trusted readers who basically would say, Keep Going!). So, I sort of tricked myself by setting up a situation where it wouldn’t be possible. After that I got an agent and did many rounds of revisions — mostly expanding things. My agent was a really good editor, not overly prescriptive, and it was never about the trends of the market, but about the book becoming its best self.

Throughout the novel, I was stunned by the swiftness with which you created potent, vivid scenes — I’m thinking of, for instance, Edie and Charlie and Marianne in the jazz bar in New Orleans, or Edie and Mae tumbling down a hill of flowers in Queens. Many chapters frame moments that are perfectly self-contained, cinematic. Is this something you were conscious of in writing and editing? How do you see your work as a screenwriter and filmmaker influencing your fiction writing?

That’s interesting. I wasn’t thinking consciously about it. I actually think screenwriting maybe just made me think about structure more, but it didn’t influence that “cinematic” quality of the writing. Screenwriting is actually very bare bones and everything is about furthering the plot or theme in a very narrow way. It usually has to stick to an accepted structure. The book is not structured in that exact way, but it is very structured. I came to writing from a background in visual art (photography). I think in images. That’s almost always my starting point.

The repercussions of dependence/interdependence between parents and children is a central theme in The Deeper the Water the Uglier the Fish. The book begins with Edie and Mae having been sent to New York to live with their father after their mother’s suicide attempt. There are consequences for the choices parents make, and children live out those consequences. Are there special risks that the writer-parent runs?

I don’t know! I think that sort of lack of boundaries between parents and children was interesting to me — it’s common, I think, this closeness between moms and daughters where they are so close they don’t entirely know where one begins and the other ends, though not to the extent of the novel. I’ve felt that as a child, not so much as the parent. As far as special risks for a writer-parent — when I’m writing it’s hard to be present as a parent. I can’t disappear into the black hole of my book and not come out for as long as a I want and simultaneously take care of my kid. Those are the risks I’ve noticed. I guess some parents who write more autobiographical stuff run the risk of their kids being really embarrassed or of violating their privacy?

Do you think all children have the feelings that Edie and Mae have about their parents, with those feelings being both frustration/irritation (“He has no right to lose it,” Edie thinks of her father very early in the book) and fascination (see Mae remembering watching Marianne stare at a book, “her fingers, disconnected from the rest of her body […] tapping something out against each other”)?

I think so. That moment when you are (usually) a teenager, and start to individuate — you probably have to hate your parents a bit in order to separate from them. The separation feels very violent, especially if you were close before. Though, I think it is also generational. I am surprised that Millennials don’t seem to clash with their parents as much as Gen Xers. I don’t know if that cultural hot take is even true. It seems true! I am sort of on the border between the two generations. In the crevasse.

Until the final section of the novel, Edie’s chapters are written in a present-tense that takes place in 1997, when she’s a teenager. In other chapters, you give voice to Mae, Dennis, Marianne, in the 2000s, the 1960s, the 1980s — not to mention more secondary characters like Charlie and Amanda, or even Marianne’s father. Each of these voices felt distinct and very much grounded in a particular historical moment. The novel, in other words, spans an incredible period in time. How did you capture history in these very brief and highly personal chapters?

When I started the novel, I thought doing it from lots of different voices would be easier, because I worried I would lose interest in sustaining one voice for the duration of a novel. I love the feeling of accumulation that happens when you are reading multiple voices. I think something clicks into place when you get used to the format and then the voices bounce off of each other in unexpected and exciting ways. As for capturing history, I don’t know. I think I just spent a long time with all of the characters and had done a ton of research on the south in the ’50s and ’60s for a different project, and that became the backstory. I had been thinking about all of it for so long, the parts you get are the tops of the icebergs. I wrote and cut so much, and even though it wasn’t in there, it informed what did eventually stay. I think a reader can tell if the writer is bluffing and hadn’t thought very deeply about the stuff that is off-screen.

The novel is haunted by possessions. Tillie Holloway, an actress starring in the film adaptation of one Dennis’s novels, describes inhabiting a role and the difficulty of knowing “where you end and others begin.” Without spoiling anything, a blurring of boundaries between self and other is the central crisis for Mae, one that she explores in adulthood as a successful photographer. These inhabitations occur with art and parenting. Do you see possession as a tool, generative, dangerous?

I think when I am writing I definitely feel possessed. It is very clear to me the moment when the writing shifts from the effortful and conscious process that I am grunting through, to a process that seems outside of my control — something bursts and then gushes out with a force. I’ve always been phobic about throwing up, but I got the stomach flu a couple years ago and it was like a demon possessed me, just like this force passing through me as I was projectile vomiting. Writing, when it’s going well, feels very similar. Parenting does not really feel like that at all to me. My daughter has never felt like an extension of myself. She has always seemed very distinctly separate and independent, even as a baby. I guess it’s possible that might change, but I doubt it.

The Deeper the Water the Uglier the Fish reminded me of other stories that show the effects of mental illness on a family. What was important to capture about neuroatypicality — in a broad sense — in this book?

I don’t know. I was not really looking up clinical diagnoses in the DSM. I think I understood Marianne and how she felt and how the people around her felt, and I have a sense of what psychiatrists would call it today, but with a lot of labels, they seem not all that useful or complete. What is typical?

Very quickly, we discover Mae has grown up to be a photographer. “Looking through the viewfinder I could never get sucked in emotionally again,” she thinks. Do you see art as a barrier? A protection?

I think art is whatever you use it for. Mae used it as a barrier and protection at first. But I think good art requires vulnerability.

Of course, then Rivka gives some crucial advice to Mae, telling her: “Art is not a shield. It is a knife. You have to bleed.” Does this ideology support the notion that the artist must be vulnerable and willing to hurt?

I think they do need to be vulnerable. Do you mean hurt others? I don’t see why they would need to hurt others. Through inattention? But yeah, I think you do need to bleed. It is exhilarating and terrifying and sometimes just awful.