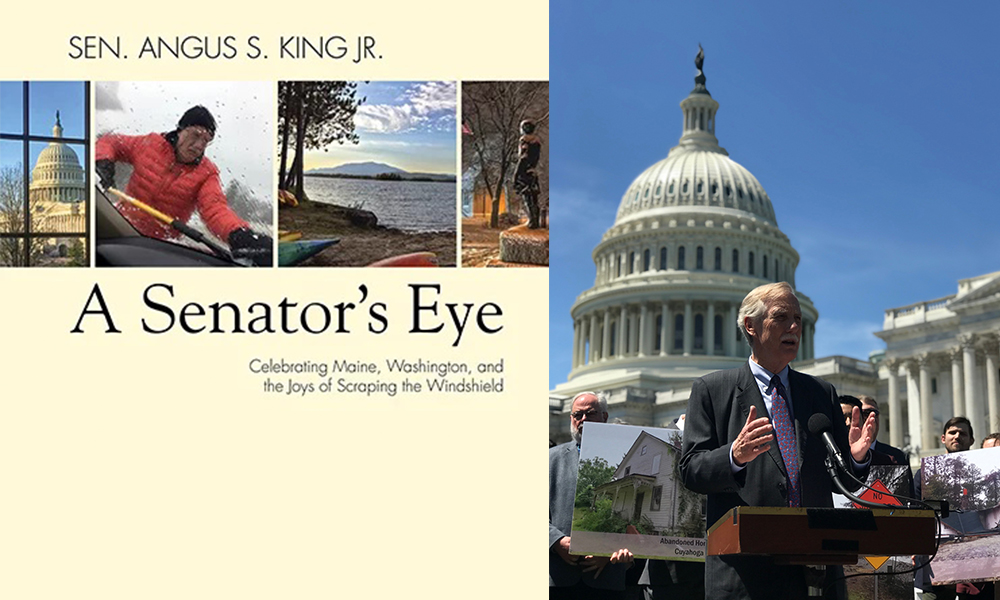

What to do when you sense your Instagram posts suddenly getting much more political? What if you already started off as a sitting US Senator? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Senator Angus King. This present conversation focuses on King’s book A Senator’s Eye: Celebrating Maine, Washington and the Joys of Scraping the Windshield, as well as on King’s Instagram account. King, Maine’s first Independent US Senator, serves on the Armed Services Committee, the Select Committee on Intelligence, the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, the Committee on the Budget, and the Committee on Rules and Administration. As a former two-term governor of Maine, King co-founded the Senate’s Former Governors Caucus (which prioritizes pragmatic policy approaches), as well as the Senate Arctic Caucus. He currently serves as Co-Chair of the Cyberspace Solarium Commission, an initiative to create America’s 21st-century cyber doctrine. Senator King also tries informally to bridge Washington’s partisan divide, by frequently bringing colleagues from both sides to his home for barbeque dinners — where political talk is banned, and the focus is getting to know one another.

¤

ANDY FITCH: The preface to A Senator’s Eye says that you didn’t know it, but you’d been waiting around your whole life for Instagram. What have you figured out about yourself, about being a Senator, and maybe about Maine or America, through posting on Instagram?

ANGUS KING: Doing the Instagrams basically combines three things I enjoy: photography, writing, and offering insights from my sort of unusual perspective. Particularly in the past year, I’d like to think that I’ve developed a new form of journalism, an op-ed with pictures. It’s not all about me. If you’ll notice, I don’t appear in most of these Instagram pictures. The pictures pick up on something bigger, and I do my best to explain how they relate to what’s happening today.

Instagram’s fairly short format demands some discipline if you want to share with people, especially when you have a lot of the work experiences I’m lucky to have right now. And these posts really do offer my personal perspective. My staff doesn’t write them, or direct the whole process. I take the pictures (except every now and then my wife sends me a good one of hers to use), and I write the essays. It took a long time to persuade my team to let me do this on my own [Laughter]. But I really appreciate that chance to share what I’m thinking and what I’m seeing.

Yeah, how do your more scripted colleagues miss out if they never get to operate as a “Senator-on-the-loose” in this way?

Maybe “unfiltered” is the best word for it. I know I can learn more and see more clearly when I don’t have to put everything in an overtly political way, but more in a kind of observer way — as someone in a pretty unique position to see certain developments close up. Sharing the insights you get from this position just feels right, and like it’s hopefully sometimes useful for people.

But the whole thing has really evolved, Andy. If you go back to the earliest pictures on my homepage, you’ll find just sort of interesting scenes, with one-sentence captions. Though in the last couple years, I’ve started to write much more in-depth about what I see happening in America and the world. Sometimes you still might get a Maine sunset. But more often now you’ll see the politicized US Postal Service, or how COVID has isolated all of us.

I also still love seeing and hearing those examples of most Senators being “pretty much ordinary Americans”: petting puppies when they can, buying laundry detergent, taking photos of the dirty dishes for their Instagram feed before getting around to wash them.

Sure, people sometimes have this perception about a Senator’s life. People often look surprised to see me in coach on a plane to Washington. But one of my most liked Instagrams came out of a flight from Washington to Maine getting canceled about a year ago. Luckily, I met up with a random group of other Maine people at the airport, and we rented a car and drove overnight to make it home. Many Americans might picture Senators flying around on their private planes and taking limos and all that kind of stuff. So I like to show Senators as just typical people like everyone else in a lot of ways — but who happen to have a job that requires a bunch of commuting back and forth to Washington.

I picture many ham-and-cheese sandwiches [Laughter].

Those all come out of the “Glamorous Life of a U.S. Senator” series. I’ve probably posted half a dozen shots.

Well part of what stands out as most distinct and endearing and instructive about this “eye” or this “I” also has to do with how it practices (and doesn’t just preach) pride of place — especially when it comes to the “great community feel” that shows up in so many of your Maine posts.

I’ll often get the question: “What makes Maine so special?” I always have the same answer: “Maine is a big small town with very long streets.” People know each other. They care about each other. You can feel a sense of community that I don’t think exists everywhere. That just becomes its own powerful presence, both back home and “away.” If you stop for gas on the New Jersey Turnpike, and the car next to you has a Maine license plate, within 30 seconds you can establish somebody you know in common.

Part of that comes from being a small state. Part comes from being the northeast corner of the country. This somewhat old-fashioned sense of community and these totally gorgeous landscapes just fit together perfectly. I mean, if you drive around Maine, it just knocks you out. I’ll often pull over, stop the car, and walk along a bridge to get a shot of a sunset over the river or something. It’s spectacular and exceptional to have these landscapes of open ocean, lakes, rivers, and mountains so close together — and with the community feel a part of all that.

For this community feel, you also frequently refer to “connections… which reach across generations.” How do these intergenerational connections shape your politics, shape your image repertoire, shape your sense of Maine, shape your sense of America itself as a place that both prioritizes diversity and constant self-reinvention — and that, at the same time, strives to maintain some sense of coherent values and collective purpose?

So for Maine we have the rototiller rule. If you borrow your neighbor’s rototiller, your obligation is to return it in as good of shape as you got it — with a full tank of gas. That summarizes my philosophy both as an individual citizen and as a public person. I have an obligation to pass down the state, the planet, and our system of government in at least as good of shape as I found them. I need to keep the next generation in mind. That’s the essence of my job. That’s why I take environmental legislation so seriously, because our generation has no right to use up the world’s resources and leave the next generations to fend for themselves. We don’t own this planet. We didn’t inherit it free of any moral or ethical obligations. We have it on loan for however many years we’re granted, maybe 70 or 80 or 90 if we get lucky. But the planet also belongs to everybody else. And if it took millions of years for fossil fuels to form, then we can’t just use those all up over a few generations.

To me, that all comes down to intergenerational ethics. Intergenerational ethics have to do with who our economy benefits. They have to do with who gets the opportunity to live a full life. They have to do with what kind of political system we hand over for the generations to come, or what kind of environment we leave for them. The whole premise of my public service comes out of these kinds of obligations. I started working on land conservation well before I became governor, or had entered public life. That’s been a consistent part of my work up through and including being one of the prime sponsors for the Great American Outdoors Act signed last month, probably the most important piece of conservation legislation we’ve had in 50 years. Again that all comes out of picking up a sense of stewardship.

Pivoting then to Washington, D.C., how do its “wide avenues, marble monuments, grand buildings and inspiring vistas” help to flesh out your sense of what the Constitution drafters might have meant by “a more perfect union”? How do those vistas, for example, keep pushing you to the thought that “Maybe, just maybe, the Senate can actually be the Senate”? Or if guides in the Capitol’s halls sometimes mistake you for a tourist — well, again, what do non-touristy senators miss out on?

If I’ve repeated any one line a few times in these Instagrams, it happens with pictures around the Capitol: “If only our work could match the magnificence of our surroundings.” The Capitol building literally inspires you. One of my favorite duties as a Senator is taking visitors into the Capitol rotunda for the first time. I still haven’t met anybody who doesn’t look up and say “Wow” or “Holy smoke” when they step into one of the world’s great indoor spaces. So I do get frustrated sometimes by how work we do in that building can seem small and petty compared with the aspirations of the Capitol’s designers and builders.

Somebody once asked how I would characterize being a Senator, in terms of academic disciplines. I told them: “Applied History, with a minor in Communications.” As a Senator, I major in applied history because that’s almost always what I read. My wife keeps telling me to try a novel sometimes [Laughter], but I just finished Ron Chernow’s amazing book on Ulysses Grant.

And then this Applied History major has a Communications minor because we’re living through history right now. I mean, I recently participated in Congress’s third ever presidential impeachment. I can’t help thinking of that experience as extraordinary. Part of my sort of wide-eyed approach to being a Senator comes from never running for public office until I’d turned 50. I had no background as a legislator, a town council member, or a Congressman. I came to all of this relatively late in life, and still get a kind of boyish “I can’t believe I’m here” feeling. I always expect someone to walk up and say: “Hey, you can’t go in there.” But as a senator, I can. It’s amazing.

Imposter syndrome, maybe?

I’ve never heard that term, but exactly [Laughter]. I walk through the Capitol and think: Holy smoke, I work here. How did this happen?

To be honest, Senator King, I sense you having those kinds of surprised and grateful reflections on life in general. Part of what I found so compelling looking back at a few years of posts, for example, has to do with tracing how the prose definitely gets more distressed more often starting in late 2016, but the world of monuments and sunsets and dramatic D.C. cityscapes, or of soothing Maine coastlines and snow, or of ordinary humble things, doesn’t change much — and still matters just as much.

Well, so let me tell you about one challenge I face. In recent months particularly, I’ll see a beautiful sunset or the mountains in Maine or the ornate buildings in Washington, but I’ll hesitate to post about it. I’ll imagine people saying: “The world’s falling down all around us. How dare you talk about sunsets?” I definitely don’t want to come across as frivolous or indifferent or immune to the fact that 170,000 Americans have died from COVID, or that our country faces tensions like we haven’t seen in decades. With so much happening that bothers me and disturbs me and offends my sense of justice and freedom and decency, I have to comment. I didn’t start off wanting to post political messages on Instagram. I don’t want to have to write: “That senator’s just pushing his ideology or his party’s advantage over the country’s best interests.” I only wanted to offer some observations.

But your question makes sense to me. Maine still has those beautiful sunsets. I still might stop the car to appreciate them. But I don’t want to send the signal that we can ignore all of the struggles in people’s lives today. I wouldn’t just post a picture of a majestic eagle I came across without thinking twice.

For sure, social media isolates everything and strips it of context. But still on the question of intergenerational connection, you do mention President Lincoln’s “funny, persuasive, and often profound writings” ringing true a century and a half later. How does a politically suspect quality like humor help to make that possible? Or what would it take today for you personally to feel comfortable offering more of those wide-eyed perspectives again?

First, here’s the typical process. The posts start with the picture. I’ll arrive someplace, and see something which strikes me. Recently, for example, I walked into the Capitol rotunda, paid my respects to John Lewis, slowly walked around his casket, and headed out. But then I turned and looked back, and this scene of the casket framed by the doorway just stunned me. John Lewis’s photo hung beside the doorway. People stood in line waiting to step in. The thought starts with an epiphany like that. The picture says it all in some ways, but still leaves space for you to add to it.

So the Instagrams show something that struck me, then offer a bit of what’s on my mind. And these days, even when you get to glimpse the sunrise or something like that, it’s hard not to think of our country. Or when President Trump used the White House as a prop last night for his convention speech, in ways so inconsistent with our history and our traditions, I don’t want my Instagrams to become yet another anti-Trump social-media campaign — but I also don’t want to hide how much this bothers me.

Certain reflections as you pass a statue of Lincoln, or of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, got me wondering if you see these Instagram posts as something like our own era’s monuments.

I think of a monument as, by definition, a symbol. A monument doesn’t just represent General Grant or Abraham Lincoln, but symbolizes what this person meant to the country, or brought to the country. So when I took a picture of General Grant’s rotunda statue recently, we had just that day in the Armed Services Committee voted to get rid of the Confederate names for US military bases. The photo and the idea came together while looking at that monument to Grant, who has no base named after him. After reading Chernow’s biography, I think of General Grant actually winning the Civil War twice, given how he as president dealt with the Ku Klux Klan, which basically threatened guerrilla war in the South. So yes, if a monument, in the best sense, reminds us of shared and fundamental principles, then I can only hope for these posts about the rotunda, or Grant, or Lincoln, or Chamberlain to offer their own modest monuments.

As your feed alternates between, say, images of “these beautiful old churches” that every Maine town has, and then of all the domes and soaring arches and vaulted ceilings in D.C. (from Reagan National Airport to Union Station to the Capitol), I also get a different sense of intergenerational connection. I think of how your illuminating shots from D.C. or Maine windows often recall stained glass. And I think of your foundational sense of our democratic self-governance as carrying something of the sacred into the largely secular present. You can call that all a total projection on my part [Laughter].

Well I’ll admit, I never thought of that. To me, the window literally gives context. It frames the scene. I don’t know if you know that I co-chair the Senate Prayer Breakfast, as a practicing Christian.

Episcopalian, right?

Exactly. My Baptist friends might call that Catholicism light [Laughter]. But part of my personality comes out of growing up with these traditions all around.

For me though, one funny thing about working in pictures is that I don’t have much artistic ability. I’ve never painted much or anything. I just know a good scene when I see one. And a window often makes those scenes for me. I’ll just stop and think: Holy smoke, look at that. I mean, for one post a couple years ago, of a bridge at night, I drove right past but thought: This is a special vision. I turned around and drove back. I parked on the road’s side, walked down to the bridge, and took the shot. Thankfully, I didn’t need to have a big, heavy SLR hanging around my neck. I don’t claim to be a good photographer. But I have a pretty good sense of picking out a good picture.

You also have a knack for describing the “faith, optimism, imagination and commitment of the local people” represented by those beautiful old Maine churches, or the “civic courage” on display with the new World Trade Center PATH station in lower Manhattan. What would you hope to see American “civic courage” look like over the next few decades?

I’ll have a hard time answering that question about the future without putting it in the context of our current situation. I’m a great believer in human nature. Human nature and human history tell us that democracy, and liberty, and respect for ordinary individuals, only happen rarely. Our democratic system is the exception, not the rule. History has many more autocrats, kings, czars, and pharaohs than elected governments. The most important sentence written in the English language says: “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” And even this radical thought was written on a desk built by a slave at Monticello. That gets to the complexities of our own American system. But I sometimes sense that all you need to know about political science comes out of the ancient Roman motto Quis custodiet Ipsos custodes: Who will guard the guardians? We give government great power over our lives, to keep us safe and serve the common good. The danger, throughout history, comes from government instead turning around and using that power to abuse us.

To me, the US Constitution offers the most sublime answer of all time to that question of Quis custodiet Ipsos custodes. So it does distress me now to see such striking failures to understand the fundamental principles of that document, which essentially divides power in effective ways so that we can both make crucial national decisions and keep out any would-be autocrat. The Federalist Papers show us that this constitutional structure gets designed explicitly to avoid concentrations of power, and the inevitable abuse that would come from those. And the Constitution Founders still feared abuses, and so adopted the Bill of Rights, which I’ve always thought of as a kind of force-field around each of us as individuals. Even if Congress passes some law which the president then signs and everything else, they still can’t take away free press, free speech, our right against self-incrimination, our right against unreasonable searches and seizures.

My biggest concerns today come from how President Trump and many Americans don’t understand or don’t respect these principles. They opt instead for: “whatever works for me right now,” or “whatever’s to my advantage.” Few developments in American politics disturb me more than a president or a powerful group attacking the free press, attacking the independence of our courts, undermining the ability of ordinary people in government to do their jobs. That erodes the underlying principles that have enabled this country to succeed like no other, and to provide unprecedented opportunities to so many different people. So that’s a pretty long lecture for an Instagram-style comment. You just got King on everything.