“I wish to live because life has within it that which is good, that which is beautiful, and that which is love. Therefore, since I have known all of these things, I have found them to be reason enough and — I wish to live. Moreover, because this is so, I wish others to live for generations and generations and generations.” –Lorraine Hansberry

Six years after her critically-lauded, award-winning A Raisin in the Sun made history on Broadway, playwright Lorraine Hansberry died at the age of 34 from cancer. For many, this is the beginning and end of Hansberry’s storied life — who, in 1959, became the youngest American playwright, the fifth woman and the only black writer to win the New York Drama Critics Circle Award for “The Best Play of the Year.” Notable, but certainly not a life of much consequence to rate a cinematic biography.

Filmmaker Tracy Heather Strain, however, was interested in telling a different story about Hansberry; a champion of the human spirit — a woman born on the Southside of Chicago during the depression after the first World War, who grew up privileged and yet was not spared the scars of the racial and political hysteria of her times; an artist-activist whose life and work were influential to civil rights, feminism, and the gay and lesbian movements.

“I always saw sparks of that fire in her — it scared me from time to time because this was in the ’50s,” recalls actor Louis Gossett, Jr. who was among the original Broadway cast of A Raisin in the Sun, which starred Sidney Poitier and Ruby Dee. “There was some kind of something like a TNT Turner Classic Movie mystery the way she behaved. She was Stella Dallas. Something was going on with her, and I didn’t know what was inside.”

Weaning down a four-hour rough cut of Hansberry’s story, Strain chronicles the extraordinary life of a rebel and champion of the human spirit in the two-hour AMERICAN MASTERS Lorraine Hansberry: Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart, premiering Friday, January 19 at 9:00 p.m. ET/PT, coinciding with the 53rd anniversary of Hansberry’s death.

¤

In the past few years, we’ve seen documentaries of artists such as Maya Angelou, Nina Simone, and James Baldwin — all contemporaries of Lorraine Hansberry. With each of these documentaries, including this one, I’m struck by this sense that the work and the words of our artistic ancestors are speaking to us now. Having worked on this film, what is it that Lorraine is saying to us?

I think Lorraine Hansberry is saying to us now what she’s always been saying, that it is our responsibility to make our country live up to its ideals. She felt very strongly about that, and it started in her childhood…That was ingrained in her, and kind of the driving force in her life, and she used art in the end — she sees what happens to her father and tries journalism – and decides to use art and theater.

I think of her as someone, sure like every other African American who waivers between hope and despair, she was ultimately hopeful. She had faith in the human race, with that quote, “I think the human race can command its own destiny and that destiny can embrace the stars,” and the idea it seemed to us that this was somehow convey through her father and that she did really believe that it was possible to make change.

I have given you this account so that you know that what I write is not based on the assumption of idyllic possibilities or innocent assessment of the true nature of life—but, rather, my own personal view that, posing one against the other, I think that the human race does command its own destiny and that destiny can eventually embrace the stars…

There’s an underlying theme in the film of “embracing the stars” that begins with a reenactment of Hansberry laying on the grass with her father looking up at the stars (“I never did learn to believe that anything could be as far away as that. Especially the stars…”) In re-reading Robert Nemiroff’s To Be Young, Gifted and Black: Lorraine Hansberry in Her Own Words, stars are also a prevalent theme throughout Hansberry’s plays, poems and personal narratives. How then did you come to Hansberry’s quote “sighted eyes / feeling heart” for the title of the film?

At one point our collaborator, Sue Schultz, was really interested in Embrace the Stars, and the current Lorraine Hansberry estate’s current trustee is Joy Gresham, but I met her mother (Jewell Handy Gresham Nemiroff, who took over the estate following the death of her husband Robert Nemiroff – Lorraine Hansberry’s ex-husband and literary executor) fortunately before she died, and I believe that was something she was thinking about.

What I tried to do was to think about what, fundamentally, was the story we were telling, and it was the story of an artist-activist. So “embrace the stars” wasn’t incorporating that artist-activist journey, it was just kind of reaching for greatness. And so, “one cannot live with sighted eyes and feeling heart and not know or react to the miseries which afflict this world,” to me was the thing she got from her family.

We have Shauneille (Perry), her cousin, and her sister (Mamie Hansberry) both reinforcing these ideas in their interviews saying that if you were given a lot you were supposed to do things to uplift the race. That, to me, connected better with the narrative that we were telling, and that narrative was decided upon because I felt frustrated that people didn’t know about Lorraine Hansberry, in general. But if they did know Lorraine Hansberry they thought of her as this kind of bougie integrationist person that wrote this play promoting integration — you know how people like to diminish people to stereotypes.

So if you are one to think [Martin Luther] King and Malcolm X were in two separate places while most of us realize they were more closely on the same page — let’s go with that scenario — people would say, “Oh, she was a King person,” as opposed to being this radical who was probably closer to the side of Malcolm X. When we get to the town hall and someone’s coming in to get you, you have every right to gett’em and kill them, and people have told me that they’re very surprised because they didn’t know Lorraine Hansberry thought like that.

It isn’t as if we got up today and said, ‘What can we do to irritate America?’ It is because that since 1619 Negroes have tried every method of communication, of transformation of their situation from petition to the vote — everything. We’ve tried it all. There isn’t anything that hasn’t been exhausted and now the charge of impatience is simply unbearable. The whole idea of debating whether or not Negroes should be able to defend themselves is an insult. If anybody does ill in your home or community, obviously you do your best to try and kill’m!

Besides the rebellious side of Hansberry, there was a playful side. Robert Nemiroff, Hansberry’s former husband, wrote that she considered herself one of “the odd-balls, the hapless funny ones” who likened herself to “Dinny Dimwit of the comic strips.” There are glimpses of this in the documentary, but not a strong sense of her whimsy. Was that something that was incongruent with the narrative you were wanting to establish?

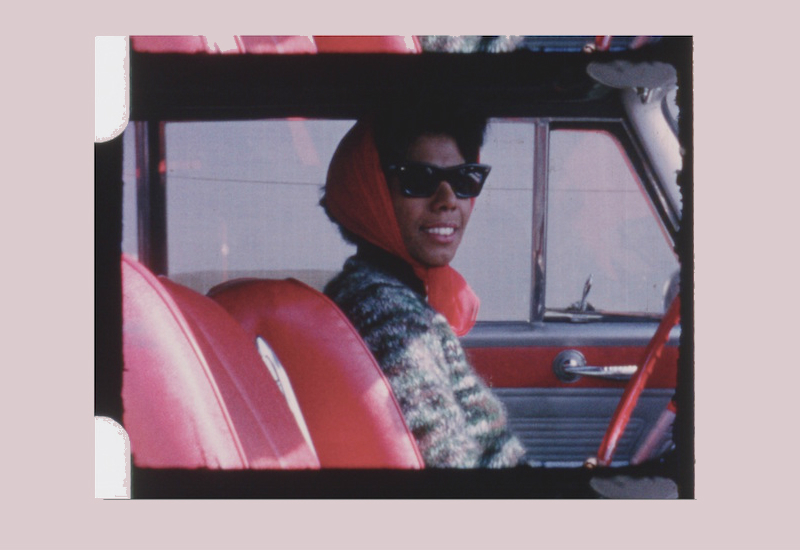

I was really aware that she was playful, she liked to make fun of herself; that she had all these clowns around her place. But all the things you see in the documentary, we didn’t have access to those when we started. We gradually got access to things or found things, and so we didn’t see the home movies until late [in the production]. So I did try to incorporate that playful side at least through the home movies because you could see her personality.

But there is other work coming out. Margaret Wilkerson’s book should be coming out soon. Imani Perry’s coming out with a book (Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry on September 18, 2018, Beacon Press); Soyica Colbert’s coming out with a book. Tricia Rose has written about Hansberry, so this is just the beginning and I hope this inspires a lot more research because she’s so complicated and she’s integrally part of the major movements during her lifetime: the Great Migration, the Great Depression, World War II, post-war, civil rights, feminism, gay and lesbian, anti-colonialism — that’s a lot to try to take on.

In exploring your own work as a storyteller, it seems as if are some thematic threads between projects like I’ll Make Me a World, on which you were a producer, or Unnatural Causes that led you to Hansberry’s story. Would you say that’s accurate?

Lorraine Hansberry, of all the things that I’ve worked on, is one of two stories that I personally wanted to tell. The second one, which is part of I’ll Make Me a World, about the black ballet dancers of the ‘50s and ‘60s — that was my idea. It’s interesting because I don’t think I’ve really thought about it, but I’m really drawn to stories about African Americans in situations that are allegedly new and unusual or outside of where we’re supposed to be. That’s representative of situations I’ve been in myself and sometimes my parents. I was a competitive gymnast — and completely too tall for it — in the 70s when I was a teenager. My parents met at Howard, and my mother was one of two women in her class who were studying architecture. She ended up leaving college to get married, like a lot of women did in the ‘50s and go with my dad to Japan where I was born. My dad is a retired civil engineer and he was an officer in the Navy in Japan.

I’ve been encountering people and thinking about the alleged fish out of water, because I don’t think there’s place that’s off-limits for African Americans. I think that if you’re drawn to the classical arts then you should do it if you’re talented, like Raven Wilkerson in I’ll Make Me a World. Most of the things that I’ve worked on have been pieces where someone has said, ‘Would you like to work on this?’ I didn’t generate the ideas.

But I’ve been blessed to work on a variety of documentaries that have actually laid the groundwork for the Lorraine Hansberry project. I worked on The Great Depression series as an associate producer. The first American Experience that I directed, Building the Alaska Highway was set during World War II, so I got to research about African Americans during that period and this idea of the “double victory” and then Unnatural Causes on infant mortality; there was a piece Lorraine published in The Village Voice about low birth weight babies even back then. We’re talking about it again because of Serena Williams sharing what happened with her, and Lorraine was talking about it in the ‘60s as an issue.

Which makes this film — and the others I mentioned earlier — so timely. These were artists were not only speaking to the times in which they lived but were very prophetic about the times we’re living in now.

The fact that those films came around finally made people hear what we were trying to do and understand, “Hey look at how successful these were, and how popular these were…” And the interesting thing, Lorraine Hansberry is credited, according to Nina Simone, for politicizing her. Nina Simone wasn’t so much a political person until she encountered Lorraine Hansberry. She and James Baldwin had these great conversations about things and, even in our film, Amiri Baraka is talking about how Lorraine already had a kind of analysis about society, that economic piece, that he didn’t have at that time. A lot of people really looked up to her.

Sadly, Maya Angelou died when we were in the middle of our Kickstarter campaign because we were looking for connections and I found something that Maya Angelou has written in one of her books about how she was performing at some club in The Village one night — and I don’t know which one it was — but Lorraine Hansberry was in the audience and she was so nervous, and I found that so interesting!

But you’re right, there is something between these people, and it’s why I think history is so important; it’s important, in particular, for African Americans to know their history and realize we come from people who have been interested in all sorts of things: intellectuals, artists, thinkers…I really love that period and the people who came of age in the aftermath of World War II. I find them so interesting, and so full of hope about our society. They were groundbreakers. And I look at how heartbroken some must be now. I’m sure they never would have imagined that certain things that are going on, namely in our society overall, but specifically for African Americans.

Bob and I have been getting divorced for many years now, meanwhile still remain the best friends either of us has. I know what I’ve always known, before consciousness even, that it will always be her; I mean, the woman. It is never the man for me.

Speaking of groundbreaking, in her personal life, Lorraine fell in love with and married Bob Nemiroff, a white, Jewish man, in 1953 when interracial marriage was illegal in half the states in country; and, later, albeit privately, began identifying herself as a lesbian even though love, ultimately alluded her for much of her life. And it seemed to be that way, too, with Maya Angelous, Nina Simone…

…and James Baldwin.

Yes. And Baldwin even wrote following her death: “Her going did not so much make me lonely as make me realize how lonely we were. We had that respect for each other which perhaps is only felt by people on the same side of the barricades, listen to the accumulating thunder o the hooves of horses and tread of tanks.” Hansberry, as you’ve depicted in the film, also writes of her loneliness, which has made me wonder if love was ultimately the sacrifice she and her contemporaries had to make for their art and their activism in the Movement at that time.

Well there was a woman that she dearly, dearly loved and I don’t know why that relationship didn’t work out; that person is known for being really smart and I think that the reason she and Nemiroff stayed connected on a sort of intellectual level — and I won’t say just intellectual, he helped take care of her even after they separated, and helped manage her financial things and he, of course, produced The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window — but I think she was looking for someone who was challenging intellectually as well as someone she just loved as well, that’s the sense I get from her papers. But she did seem to be lonely a lot. But I like to provide this caveat that these are her private journals, and I’m sure we’ve all had pity party weeks where if you were to write it down it might seem like, ‘Oh my gosh!’

Watching this documentary and thinking about, say, having read Octavia Butler’s personal journals — which were exhibited last summer at the Huntington Library — that, here again is a great writer, but love — or at least romantic love — alludes her.

I think it’s very challenging to be an African American writer. There’s a quote at the end of the film with James Baldwin saying: “Every artist, every writer under the hammer, but the black writer lives under something much worse — the strain can kill you.” Because there are people who are good at words, they’re called upon to be spokespeople. To write, as you know, you have to sit there; you have to be by yourself and be productive. The phone rings—and nowadays we have email and other things to interrupt us — with: “Can you do this? Can you do that?” And I think there’s this tug between knowing you can eventually convince people or sway an audience or rally the troops with your words and sitting down and trying to get what’s in your head out. I think it’s a challenge, and love — it’s hard to fit in everything in a life.

And speaking of sway, Baldwin once said that Lorraine Hansberry could get through to anyone except for Bobby Kennedy, who was attorney general to JFK. You highlight that critical meeting in 1963 in your film, and it really is one of the more tugging, dramatic scenes of the documentary.

I’m so glad you felt that way because we really did try to make that moment that way. Without saying it explicitly, that’s part of our story. Here she was, a chance to speak as close to the president as it can get, and here’s this hyper-verbal lady and she can’t get through. Can you imagine — and Margaret Wilkerson said this in one of the two interviews we did with her, but it’s not in the film — thinking you’re going to climb a hill, but it’s a mountain?