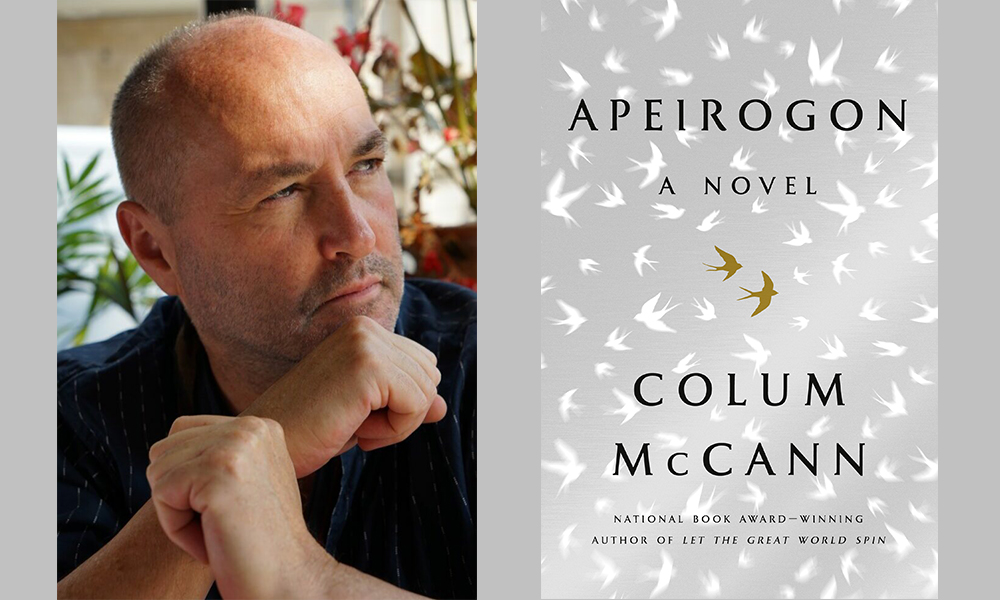

Colum McCann is the kind of person who establishes instant rapport with others. When we spoke on Skype in July, he immediately leaned forward, trying to read the titles of the books stacked on the shelf behind me, as if figuring out what makes me tick. He did, in fact, spend five years figuring out what makes Palestinians and Israelis tick. The result, a staggering book named Apeirogon: A Novel (Random House, 2020), details the parallel worlds of Bassam Aramin and Rami Elhanan, a Palestinian and an Israeli who both lost daughters in the ongoing conflict. McCann, who teaches creative writing at Hunter College, won the National Book Award for Let the Great World Spin, (Random House, 2009) and is the recipient of numerous other literary accolades.

Many of his books have been translated into foreign languages. As co-founder of Narrative 4, a non-profit global story exchange organization, McCann is particularly interested in having Israelis and Palestinians read Apeirogon in their mother tongues. To date, he has been pretty much met by a brick wall — so far, no publisher has agreed to translate and distribute Apeirogon in either Arabic or Hebrew.

¤

JOANNA CHEN: Even your own publisher in Israel, Am Oved, ultimately turned the book down.

COLUM MCCANN: I was shocked, to be honest. I want people to read the book. I want to extend the conversation to the innate nature of the book itself and its themes. I worked really hard to get it to a place where I felt I could stand behind everything that was being said, whether that be emotionally or factually, I probably worked harder on this book in terms of fact-checking and everything else than any other book I’ve worked on in my life. A lot of people gave me some really profound and serious feedback; I was hoping it would open up a debate. Apeirogon is appearing in Lithuanian, Catalonian, French, Spanish, German, Polish, and even in some less widely used languages, such as Croatian. It will be translated into 30+ languages — I really hope that Hebrew and Arabic will eventually be among them.

Am Oved said a stranger wouldn’t understand.

I respect the fact that they said no, but I don’t respect the fact that they say a stranger wouldn’t understand this. It seems to me a stranger can come in and do precisely what they’re talking about.

Literary translation, to my mind, provides an essential bridge into other cultures and beliefs, and opinions. Perhaps Israelis and Palestinians aren’t ready to cross this bridge.

There was more positive interest, I have to say, coming from the Arabic language world… Just last week I had someone get in touch with me saying — “I want to translate this into Arabic. Is there anything I can do to translate this?”

But Arabic and Hebrew language publishers feel the book is too hot to handle.

Is it something that’s a little bit uncomfortable? Yes. But literature should be uncomfortable. Literature should sort of rock people back on their toes. It should be something that knocks people off their comfortable balance and confronts some of the heartbreak but also confronts some of the multitudinous aspects of this. I think the brave artist, or the brave reader, or the brave publisher, is one who says, “I am going to scuff this up a little bit — I am going to throw a little spanner in the works so we can begin to look at ourselves a little differently.” The job of the artist is to complicate things and to talk about the multitudinous aspect of our character.

Rami and Bassam are longtime members of the Parents’ Circle Family Forum, an organization that advocates acknowledging the narrative of others.

I like Walt Whitman’s idea: “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself. I am large, I contain multitudes.” Rami and Bassam do this. They’re complicated people with complicated emotions. But in the end their fundamental duty is toward each other’s humanity, recognizing you can maybe turn grief into a weapon for dialogue and for peace. This is what they call for. They say, “If I don’t know you above ground, I will end up knowing you six feet below ground.” And I think that’s a powerful argument.

Did your own experiences growing up in Ireland impact your treatment of the Middle East conflict?

Yes, I’m from Dublin but my mother’s from Derry. Every summer we’d get on a bus and go to Derry for at least two weeks. On that bus, we’d get stopped at the checkpoint, on the border, where immediately things changed, the postboxes became red, the roads changed and widened, and soldiers would come on the bus and we would have to step off, or change buses.

I had extended family in Northern Ireland who were — I suppose it’s safe to say — peripherally involved in what was going on, so I grew up in a time when we were not at peace. I also managed to see what shape peace might possibly take, even though it’s shaky right now. But what was done by the Women’s Coalition, for example, in Northern Ireland, reminds me very much of what the women in black, Machsom Watch, are doing today in Israel. You know, people on the ground, making a difference.

Apeirogon risks having people roll their eyes and say, “I’ve already read that a thousand times.” The thought crossed my own mind, to be honest.

I knew I had to tell this one differently and I knew I had to gamble. There are lots of powerful narratives out there. I thought if I can shake up form, shake up the literary form, I can perhaps disrupt in the way that I want to disrupt. Yes, it’s a conventional enough story. Oh yeah, I’ve seen that before. But my belief in these men and in the fact it had to be told in a different way was paramount to me.

The great writer John Burger, who died a few years ago said: “Never again will a single story be told as if it were the only one.” And he also suggested that in order for stories to live they have to be told over and over and over again. Even in the face of adversity. Even if they feel like they’re being flung into the void. Because eventually someone is going to hear it. and I think that what the women did in Northern Ireland and what these women are doing in Israel and in Palestine, what these young people who are going out and protesting are doing, and it seems like they’re throwing their voices into the void, but they’re actually keeping the voice alive — and someday it’ll twirl up like some whirlwind and this will be important.

How did this impact the crafting of the narrative?

When I started it, to be honest with you, I thought I’d do it in maybe 100 sections, and the more I got into it the more I realized how hard it was. It began to be symphonic for me — and I thought, 365 sections — and then it became so alarmingly clear to me when I realized that Rami and Bassam were telling their stories in order to keep their daughters alive — which is like Scheherazade. I thought, That’s what it is, it’s One Thousand and One Nights, and I have got to echo it.

Symphonic is a good way to describe it.

It’s a conventional narrative that takes place over 24 hours — and it also becomes a compendium of experiences. I am so proud of my publishers for allowing me to call it Apeirogon, which means “multifaceted”, and it really changed things straight away.

Yes, who can even pronounce that word.

I only ever met two people who know what this word means! I discovered it accidentally, and for the publishers to have the bravery to call it that — they’re even calling it Apeirogon in Germany and France — is quite something. I wanted to be brave with this one. It felt like a certain amount of culmination.

The book is multifaceted, not just in its opinions but also in structure. It flits around from subject to subject, crossing physical and temporal boundaries, zigzagging through people’s lives.

Do you know who my best readers are? The young kids, 15 to 16 years old. They are used to jumping around from subject to subject, they do it online all the time. So we can jump from migratory birds to tightropes and the kids get it. I’ve never had as many letters from 15- and 16- year-olds for any other book of mine.

This leads me on to the work you do with youth at Narrative 4 and the global story exchange that you facilitate there.

We have a number of projects going on now in Nablus, South Africa, the South Bronx, and Kentucky, where we turn empathy for each other into action. It’s driven by young people and teachers, and inspired a little by artists. It’s good work. We’ve worked in 12 countries now, to my mind the only way we’re going to get through this is by getting to know one another in more profound ways.

Telling stories.

Because stories are dangerous things, stories are tough, it’s not some airy-fairy pie-in-the-sky notion, you know. So we find that when these kids step into someone else’s shoes, something extraordinary happens.