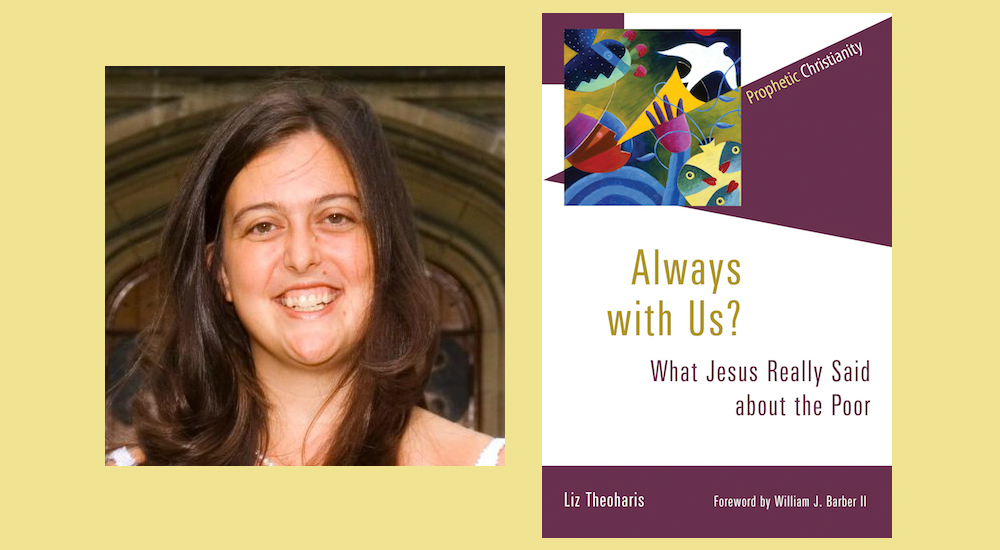

Did you, like me, have a well-rehearsed escape route when dropped off for church (or some equivalent), striding through the front door then sneaking out the back, stopping in Walgreens to peruse wrestling magazines, then picking up a quick Burger King croissanwich (or some equivalent)? Did you ever wonder, in the intervening years, how you now might relate to the smartest, most idealistic, most impressive of your spiritual school classmates? And if that classmate later emerged as a respected minister and internationally prominent advocate for poor people, where might the conversation move then? When I myself wanted answers to such questions, I called up the Reverend Dr. Liz Theoharis. This present talk (transcribed by Phoebe Kaufman) focuses on Theoharis’s book Always with Us?: What Jesus Really Said about the Poor. Theoharis, an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA), co-chairs (with the Reverend Dr. William J. Barber II) the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival. She co-directs the Kairos Center for Religions, Rights, and Social Justice, and is the founding coordinator of the Poverty Initiative at Union Theological Seminary. The Poor People’s Campaign will begin 40 days of coordinated action this Mother’s Day.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Your preface prioritizes the development “of a liberation theology for the United States in the twenty-first century.” Your book articulates the scriptural development, promotes the activist development, and charts the lived experiential developments of such a present-day liberation theology. And this liberation theology prioritizes a “reading the Bible with the poor” approach, an approach that situates poor people as “epistemological, political, and moral agents of change in our society.” I’ll want to get to working with poor people, but first could you offer several perhaps overlapping conceptions of what it might mean to “read with the poor” (for instance: reading with poor people in mind, reading from a political perspective aligned to poor people, reading in participatory social communities that include poor people)? And could you outline how such “reading with the poor” approaches depart from previously prevailing mainstream Christian conceptions of poverty, as associated with Matthew’s pronouncement that “the poor you will always have with you” — the interpretive legacy of which your book describes as the “primary roadblock” preventing Christians from demanding (and helping to bring about) poverty’s immediate end?

LIZ THEOHARIS: Reading with the poor happens on a number of levels. I and many folks I organize with have a practice of doing Bible studies within the context of social-movement organizing. We’ll actually pull out a Bible, study it with a community, and connect our readings to the conditions we see people living under. We’ll discuss the organizing strategies that poor people employ to try to end the poverty in their lives, in their families’ lives, in their communities, and in the world at large.

And then to develop this methodology further, I and others teach a variety of classes, both in seminary settings and community settings, where folks think about how the Bible approaches certain social issues, and how to use the Bible as a tool for their and their community’s liberation. Here we specifically think through what it means to read the Bible with organized poor people, and what types of responses can come from that. We also explore reading with the poor as a philosophical position, in terms of the perspectives that Biblical stories place before us.

Karl Barth has this idea that you have the Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other. You need to stay attuned to struggles for justice that poor people wage in their communities, in this country, in the world. You also need to ask: “What does the Bible have to say about these struggles poor people are waging?” In the organizing work I do, we often talk about the plight, the fight, and the insight of poor people. We ask: “What does the Bible have to say about all those things?” I read the Bible as describing the conditions people experience during various imperial regimes. It describes injustice, struggle, and movement building. Sometimes people don’t talk about the Bible this way, but the stories of Jesus, of the prophets, or of the Deuteronomic Code teach us how people banded together to right wrongs in their communities, and built movements for justice and liberation.

I sense significant conceptual overlap here to contemporary critiques of unrepresentative, or patronizing, or top-down leadership amid any number of avowedly progressive causes. First though, could you offer some additional historical/theological/scholarly context for both longstanding and then more recent emphases upon this reading-with-the-poor approach among Christian progressives? Could you maybe introduce the Union Theological Seminary here by describing its own ongoing efforts (perhaps a core mission) to clarify the proposition that: “although the Bible may be the product of the powerful trying to acculturate lessons, traditions, and practices of the poor, the fact that societies erupt when they read it and those in power try to control oppressed people’s access to it sheds light on the reality that it is also a revolutionary document”? And how does your work specifically at the Kairos Center fit among these broader efforts?

Union Theological Seminary is a very special place. I was introduced to Union Seminary as an activist, not as someone seeking to do graduate school. I came to Union’s campus in 1999 at the culmination of a month-long march by poor and homeless families, including people from more than 20 countries across the Americas and Europe. The one place willing to welcome all of us was Union, the birthplace of liberation theology in the United States. A lot of Black theology, feminist theology, queer theology has come out of Union over the years. If you look at social-justice struggles across the country and world today, many with people of faith involved have some connection to Union.

I decided to study at Union, and to start the Poverty Initiative, and Kairos: The Center of Religions, Rights, and Social Justice, because of that history. Union helped me and many others see the role that theology and Biblical study can play in contemporary social-justice movements. Union poses to its students and alums the primary question of: “What role can and does public theology play in our hurting world today?” My own work at Union tries to raise up generations of religious and community leaders committed to building a movement to end poverty and racism, and to promote social justice in our country and world. A lot of this work, including the Biblical scholarship components, has its roots in Union’s long history of social-justice prophetic Christianity. And this work also has roots in poor people organizing and finding their voice and developing their own theologies. At Union, I found professors and scholars who saw that theological insight comes from lots of places — including and especially struggle, including and especially leaders from the ranks of the poor. So I think of Union as a place where you go to combine rigorous scholarship, theology, and historical analysis with an equally rigorous and active concern for social justice.

And then how has your more recent activist work renewed your own reading practice as modeled in Always with Us?

The Kairos Center has explored relationships among theology, religion, and social-justice work as it has prepared for and organized the launch of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival. This Poor People’s Campaign has learned many lessons from history, including from the Poor People’s Campaign that Dr. King launched in the last year of his life. It also has roots in Biblical and theological social-justice movements throughout history, including the Jesus movement as described in New Testament stories.

As I’ve traveled around the country these past few years, I’ve often discussed Biblical stories within this context of trying to launch a Poor People’s Campaign. I’ll ask myself and others: “What theological obstacles exist that get in the way of us ending poverty?” This whole book comes directly out of that type of questioning. For the past 25 years, basically not a week has gone by when somebody (both people who do not consider themselves Christians, and very devout folks) hasn’t quoted that Matthew passage “the poor will be with you always” (often taken out of context) when I raise the goal of ending poverty. They’ll paraphrase Jesus’s statement, made at one of the last meals with his disciples, as a justification for poverty’s inevitable and eternal presence. They themselves might consider poverty unfortunate, but they’ll argue that if God wanted to end poverty, God would do so.

Over time, I have found that if you don’t address this reflexive, hegemonic assumption of what the Bible says about poverty, then you can’t do substantial work to end poverty. If people believe that our faith traditions condone poverty, that these traditions consider poverty inevitable and acceptable, then these people can’t see the contradiction between some of their deepest core beliefs and the work of social justice. But if instead you contextualize for them certain Biblical passages and offer fresh interpretations of those passages (which have been used as real obstacles to social-justice work), then they can agree that when Jesus says “The poor will be with you always,” he means something quite opposite from that hegemonic interpretation. He means that if you all stand up for justice and try to end poverty in your lives, then something different can happen.

Here, doing Bible studies and information sessions in relation to the Poor People’s Campaign really has shaped my interpretations of these texts. These interactions have allowed me to see the Bible as a living document, a document that changes when people interpret it. And these interactions also have helped me to recognize that, within its own historical setting and context, the Bible focuses on a group of poor people who have come together to organize for a more just society, and who believe they have God on their side. Borrowing their core values from the prophets, they have pulled together some kind of liberation campaign. So when you think about the Bible that way (with its emphasis, for example, on providing health care and living wages), you can compare it to our present and call for a similar revival of values.

I’ll admit your claim that “God hates poverty” left me wondering why, then, most species, humans included, probably have faced conditions of scarcity akin to poverty throughout life’s history. But I get that your book also makes theological moves I don’t fully grasp — here, for instance, in terms of reframing poverty not as some supposed individual sin or problem, but as society’s systemic sin or problem. Or “God hates poverty” makes perhaps a much stronger social-justice case then “God loves the poor.” And amid such parsings and argumentative implications, could you also provide interpretive context for your critique of tendencies to “spiritualize poverty”? How does spiritualizing poverty sit alongside, say, Always with Us characterizing poor people as virtuous, as in assertions such as “God is present in the poor”? Does this type of assumption take away a poor person’s freedom to depart from virtue? Or more broadly: does the very concept of “poor people” stem from a privileged person’s perspective (would poor people tend to think of themselves as “ordinary people” more often than as “poor people”)? If so, then could you sketch the extent to which those of us embracing an elective affinity through processes of reading with the poor, of ministering to the poor (or I even think of a divinity’s son taking on the embodied existence of a poor person) might need to confront prospects for our own privileged status to confound these efforts at dispelling poverty? And/or when can assigning virtue to the poor come awkwardly close to assigning sin to the poor — with both moralistic designations obscuring the crucial fact that poverty plays out at a macro-structural level, independent of individual vice or virtue? And/or much more concretely: as your book gradually details its own focus on “the organized poor,” I’ll wonder: who gets to determine which poor people’s perspectives we consider exemplary, or authentic, or self-aware enough to read with? Would you frame organized poor white conservatives as equally virtuous? And I know you Liz as someone who would have thought through this tangled complex of concerns much earlier and in much greater depth than I ever could. So could you describe your own personal experience grappling with related questions and/or engaging in a social practice that ultimately made such questions feel moot.

First, when I describe someone spiritualizing poverty, I mean when they overlook the material elements of life, as if the Bible doesn’t address material poverty, only spiritual poverty, only people who don’t have enough faith in God or who don’t count their blessings enough. The relationship between your material body and God somehow doesn’t come into play in all of that.

Okay, then I think of critiquing spiritualized poverty as somewhat similar to Susan Sontag critiquing an idiom of disease, of cancer — treating these terms as metaphors separate from the lived pain people suffer.

Exactly. And then for your broader question, I have thoughts in lots of different directions. On the idea that God hates poverty, and how that point informs all of these other Biblical passages, starting in Genesis and continuing through Revelations, I always come back to stories where people’s humanity and material conditions matter to God. In Deuteronomy, how you honor God comes out of how you treat people’s material needs in the here and now. Throughout the Hebrew scriptures, the prophets’ anger comes from them seeing poor people oppressed, denied their rights, losing their homes, denied healthcare, denied living wages. Over and over in the Bible, God too gets angry because of these material injustices. The Bible keeps developing further this strong grounding in humanity’s need to live fruitful, abundant lives in the world, in the present moment. In Exodus, when people complain, they get manna. In Isaiah, when people lose their homes, they get the streets restored. In the feeding of the five thousand, when people gather to hear Jesus but find themselves hungry, they get food.

And like you mentioned, to say that God hates poverty makes a pretty strong statement against the assumption that God accepts poverty. But I do also agree that once you start talking about finding God in the poor, about the poor being God’s chosen people, then that can seem like its own form of moralizing. Here I find it especially helpful to say that the Bible takes the very strong position that people deserve to live abundant lives whether they’re good people or not. The Bible doesn’t present God as thinking that we should deprive anybody because they act wrong or their parents act wrong. Over and over again, Biblical stories address this topic. And even Jesus in the New Testament doesn’t really come across as the nice, friendly, humble, easygoing figure some people would like to make him. Jesus in these stories keeps company with the rabble rousers, the marginalized, the drunks. The Bible makes clear that whether you deserve something or not according to moral conventions, you deserve it in God’s eyes. Whether you’ve lived the life of a great person or a miserable person, whether you’ve been generous or selfish, you deserve it because God created enough for everyone to have.

So on some level, the moralizing question becomes a bit irrelevant. No matter what, people deserve to live abundant lives. As for why I say that God is in the poor, again that’s in part because the dominant view in society would say the opposite. You have to counteract that dominant assumption by going back and looking historically and Biblically. The Hebrew people, historically, were most likely this band of marginalized people thrown out of society, because they were not needed anymore. So again, socio-historically, the Bible tells stories of poor and marginalized people’s movements, with God on their side, forming and coming to right the wrongs of society.

Today one dominant assumption might tell us that people are poor because they sin, or because they did something to deserve being poor and got out of their right relationship with God. But the Bible reverses that, and presents poverty itself as a sin and affront against God. God stands with people in their struggles. God doesn’t stand for poverty.

The book of James, a very radical text, says that rich people who fail to pay their workers should weep because of what will come to them. The workers they have failed to pay have cried out against them, and those cries have reached the ears of God. Again that common theme echoes throughout Biblical texts, that injustice reaches God’s ears. God hears people’s cries, and God intervenes. Now, we might have lots of different ideas of what it looks like for God to intervene. This could mean that a community bands together and says “Enough is enough.” It doesn’t have to involve some supernatural event. But God plays a role in poor people’s struggle to say: “We deserve to thrive in this society.” This point doesn’t deny that people have flaws, mess up, act undeserving. But we’ve already established that people are deserving, just for being people, just because we’re all created by God.

Here could we pivot to “working with the poor,” especially given the material emphases you find throughout these Biblical narratives? I value for instance, in your transcript of a Bible-study session, your emphasis upon posing questions rather than providing answers. And while I encounter many arguments at present that poor people should lead progressive movements, I particularly appreciate your accounts of how poor people already in fact do lead a burgeoning array of anti-poverty campaigns, projects, initiatives. So I would love to hear how you might situate poor people’s leadership of social-justice movements amid contemporary calls, say, for leaderless social-justice movements, and/or for movements in which so-called leaders really serve a more modest role as tacticians and tireless coordinators — rather than as charismatic prescriptive prima donnas. How has poor people’s agency shaped the efforts in which you take part, and how then would you characterize your own role as, nonetheless, a leader within such movements?

I consider this question of leadership of and by the poor central to the work I do. Back in the early 1990s, I got introduced to a movement of homeless people called the National Union of the Homeless. In the late 80s and throughout the 90s, in 25 cities across the country, poor and homeless families launched this organizing drive which, at its height, had upwards of 30,000 people engaged on a regular basis. Folks coordinated simultaneous actions in 73 cities one winter. Folks won the right for people to vote whether or not they had a fixed address. I saw that people with little or nothing to lose could organize, unite, and develop urgent, creative, and inspiring ways to bring about real change.

Ever since then, I have seen poor people (farm workers, low-wage workers, homeless folks, people without healthcare) form their own organizations, put together impressive campaigns, do deep and rigorous research to figure out real solutions to problems they face, and win some real victories. Often this story doesn’t get told. But historically, initiatives led by people directly impacted by pressing problems have brought about successful efforts for change. The abolitionist movement had the strong leadership of Harriet “Moses” Tubman, Frederick Douglass, slaves and ex-slaves. The suffrage movement had powerful women leaders. The Civil Rights movement, the American Indian movement, and the Chicano movement had strong people of color leading. The list goes on. So major change has never happened in this country without those who faced the most serious problems taking the lead. Now, other folks have had to play leadership roles, too. There’s no exclusive leadership. Everybody, both in organized groups and as individuals, needs to play a leadership role.

Frederick Douglass got famous for saying: “Those who would be free must strike the first blow.” That idea shapes this whole approach I come out of. Those most impacted need to play significant, urgent, vibrant leadership roles. And they are. And I do still believe that you need leaders. You need folks from all walks of life with diverse talents, skills, and experiences. With leaderless movements, those already in power will get to maintain their power, because that power is definitely not leaderless. Those trying to uphold the status quo come up with slogans like “Power corrupts” but they don’t give up their power. So we can have shared leadership. We can have cooperative leadership. But we need leadership, because that’s how societies take care of and organize themselves.

Again, I’ve learned all of this through movement work. I did a bunch of work down in Immokalee Florida in the late 90s and early 2000s. Folks have made some real changes for farm workers in Southwest Florida and across the U.S. These farm workers, many undocumented, have been paid poverty wages for 30 to 40 years, and actually had to train the Justice Department on how to identify and break up modern-day debt-slave rings in the American South in the 20th and 21st centuries. Or I learned from working with the Welfare Rights movement in Detroit, where people have had their water shut off not only for the last couple of years, but really for the past decade. The Michigan Welfare Rights Organization came together with a powerful team of lawyers, scholars, and poor folks to develop a water-affordability plan that could have entirely eliminated these water cutoffs. Because the city has not implemented it, now we instead see upwards of 100,000 households without water in Detroit. But the solution for water affordability and ailing infrastructure exists and came from poor people themselves. I’ve seen example after example of poor people leading social-justice efforts and coming up with solutions — not just for problems disproportionately impacting them, but also for broader problems within society at large. Poor people are leading a budding moral movement in this country.

For the Poor People’s Campaign, we’ve taken a lot of leadership lessons from someone like Dr. King. Dr. King himself was not a poor person, but he did help cultivate leadership by poor people, and he became a leader of this poor people’s movement. I’ve always loved his statement that “I choose to identify with the underprivileged. I choose to identify with the poor. If they’re going that way, I’m going that way, too.” Here you see the individual leadership of someone who has decided to side with, to throw his lot in life in with, a whole grouping of oppressed and marginalized communities. He presents this powerful leadership of the Poor People’s Campaign in ‘67 and ‘68, but then when he get assassinated, the real vision and implementation of that vision get stopped in their tracks — on some level, because we don’t have enough Martin Luther Kings, enough people clear and committed to uniting and organizing poor people across racial and geographical lines.

From that history I’ve learned that we don’t just need another person like Martin Luther King — we need a lot of people like Martin Luther King. And my experiences across this country suggest that we do have a lot of those heroes and heroines organizing in our communities, changing things for the better, developing the vision of something big that could be. We now need for those leaders to come together and figure out how we’ll reach the promised land. We need their leadership. Of course sometimes these types of leaders get overlooked by TV, by press coverage, when the media does focus on social-justice movements and leaders. So sometimes we miss out on seeing the powerful efforts of poor people already leading the way to greater justice for all.

Within that context, I wonder if we could address what I at least see as avowedly Christian and avowedly secular progressive communities failing to come together as much as they could. First though, just to clarify: are you a practicing minister with a congregation?

I don’t have a congregation. I was ordained to do this work at the Kairos Center and the Poverty Initiative. My ministry takes place in the traveling I do with Reverend William Barber to build this Poor People’s Campaign, and I consider building this freedom church of the poor my ministry. I preach, but I preach in lots of churches. I lead Bible studies, but I do so in lots of settings. I do minister to leaders in this movement work.

So I hope here to put together a question that combines liberation theology and everyday ministry. When I read your book, I sense its primary aspiration as one of empowering socially marginalized and/or oppressed people to shape their own destinies (and to help shape our collective destiny). When I think about the role of a minister, I picture ministers providing crucial nurturing, therapeutic, protective resources to some of the people who need these most. But as a nonbeliever, I find it difficult to understand precisely how these empowering and these restorative efforts come together. Throughout this book, I rest assured that you remain acutely aware of paternalistic and patriarchal legacies of the religious (and of course, basically all other) institutions that shape our present social circumstances. But when you describe a great need, following the Jewish Wars of 66-70 CE, “to locate leaders who would intervene on behalf of the majority poor and dispossessed,” when you describe Jesus as “such a leader and so much more…a popularly acclaimed king who comes to address the social-economic crises of the late Second Temple period…a savior, 2000 years later, whose redemptive laws and prophetic witness still hold great power for millions worldwide,” I still look for guidance on how to square notions of charismatic, redemptive, messianic leadership with present-day calls for fostering poor people’s agency. So again, acknowledging that my own questions derive from a place of comfort and privilege: does Christianity feel less empowering than it could, due to the presence of divine and/or otherwise charismatic intermediaries? Or could you begin to dissolve this binary I clumsily have set up, and discuss how one goes about both ministering to a flock and empowering citizens — perhaps in relation to your intriguing reading of the Matthew narrative’s anointment scene, in which an unnamed woman “is able to see that Jesus is in need rather than being someone who himself is always helping the needy…. So, this act of anointing by the unnamed woman is an act of care and love for a poor person”?

When you bring up that Biblical anointing scene and these questions of messianic leadership, I sense that you’ve basically found where the next book, coming out of this one, will need to go. The Bible’s challenging concept of the messiah actually can help to answer this question of: “How do you both minister to and empower people, and set them out to change the world?” Jesus has become how we think about the messiah, but this obscures the larger archetype and the many roles that messiahs and Christs are to play in society. We might think that, since Jesus plays this role, nobody else has to. But this idea of Jesus as the sole messiah just isn’t historically or Biblically true.

Jesus’s time brought forth lots of messiahs, lots of prophetic leaders organizing in lots of different ways: some more violently, some more radically, some more ascetically. And if you look today at all the different strands of organizing, you’ll find anarchistic folks, folks particularly concerned with racial justice, folks taking up the Fight for Fifteen and other labor struggles, folks demanding pro-environmental policies. This diversity brings debates about tactics, strategy, and movement-building, echoing our historical understanding of Jesus’s time — with Jesus as just one of many leaders all debating: “What would it look like to try to change society? How should we go about it? How do we resist Rome?” Here you can start to see why the different Gospels present such different perspectives, why some stories don’t make it into the official canon, why it can get hard to tell which writers actually participated in the Jesus movement. The Jesus movement has this robust organizing and social-justice culture happening all around it. Jesus emerges as a key leader, but not the only leader. Jesus doesn’t just right society’s wrongs once and for all, but instead shows that to follow his lead in this faith tradition, you yourself have to do that work. So the dichotomy between doing justice work and ministering to people’s day-to-day needs starts to seem less stark.

The word “Christian” only appears once in the Bible, specifically to describe this particular social-justice movement. Jesus himself was born a Jew and died a Jew. He was never a Christian. The interreligious Jesus movement united Jews, gentiles, folks who had all types of worshipping practices. So when we try to define what it means to be a Christian, we should follow the way established by Jesus — this way of having faith so that the oppressive empire doesn’t get the last word, so that poor and marginalized people can come together to change things.

It becomes impossible then to conceive of a church that doesn’t fully involve itself in the work of social justice. Folks say you can find between two thousand and twenty-five hundred Biblical passages about justice for the poor — so many that, if you cut out these passages, the whole Bible falls apart. So just ministering to people and just having them get by in life means maintaining, which I don’t think of as a Christian project. Fostering Christian justice means by necessity that you follow the prophetic leaders who have come before (which isn’t to make people not doing justice work feel bad, but to reframe how we understand Christianity, the church, religion). According to the Bible, you can’t really follow this religion without placing justice and movement-making at the center.

To do that, you have to take care of people’s (especially poor people’s) needs. William Coffin, the former Riverside Church pastor (and one of the fathers of the Peace and Justice movement, of nuclear-free zones, and related projects), was a friend and early supporter of a bunch of the work I was doing. He always said that if you want folks to move forward on a justice cause, you have to minister to their day-to-day needs twice as much. This doesn’t mean that you fail to take care of the sick, or to make sure people’s spiritual questions get answered, but that you do such work within the broader context of needing to right society’s wrongs. You can’t really answer people’s spiritual questions so long as society still creates these injustices.

Here could you outline the distinction Always with Us makes between performing acts of charity and fighting for social justice? I appreciate, for example, your book’s point that individuals with the means for performing acts of charity often have arrived at this privileged position through direct and/or indirect operations of systemic economic exploitation within more marginalized communities. But I also wonder: let’s say somebody believes in capitalism as a necessary means for generating wealth in the first place, before anyone could even worry about distributing it across society. Let’s say such a person then proactively pursues an expansive conception of charity as a means of alleviating disparities produced by capitalist production. I might disagree with this person’s theory of economics, but must I fundamentally disagree with and reject this person’s practice of charity? Must I characterize this approach to charity as a form of comfortable, complicit, social “hypocrisy”? And/or more broadly, how might you characterize your relationship with the many Christians who have adopted a more quietest, non-systemic means of addressing poverty, but who nonetheless do good work? To what extent do you see your book seeking to address and to persuade such Christians to adopt a more progressive agenda, and to what extent do you see your book as judging them and/or simply speaking to a different audience?

I consider this question of charity, or this tension between charity versus justice, particularly important among Christians and other folks motivated to do good by their faith. Charity remains such a dominant response to injustice. Charity comes out of a good place, especially when it comes from individual people just wanting to alleviate others’ suffering. But this book does take on charity in pretty harsh terms, because the thought that one can do charity instead of doing justice, or that the Bible promotes charity and not justice, is a dangerous, hurting, and damning idea. If you don’t understand how charity upholds the status quo, if you conceive of charity as the only appropriate response to poverty and want, if you consider ending injustice impossible, then you’ve stopped your creative response to this situation a little too soon. You’ve missed out on the model Jesus gives us. I don’t think that Jesus says we can address inequality and rampant deprivation by redistributing a little bit.

Of course almsgiving remains an important and useful practice in many different faith traditions, including Christianity. I respect people who give, out of their poverty or out of their wealth, so that others might have some. So I don’t mean to judge anybody, but I do mean to put out a very strong critique, because I believe Jesus lays out that critique in the Bible. If you can’t call out the problematic role that charity plays in this society, then you can’t seriously present any real solutions to poverty. We do need charity, and I’ve always questioned church programs and other anti-poverty efforts that don’t focus on meeting the immediate needs of poor people. I think that progressives often feel quite proud of themselves for doing something other than charity work, even as they fail to assist the people with the most desperate needs. I don’t consider that a solution, or a right response. We must meet people’s immediate needs. We must show compassion and care every step of the way on the justice path. But to leave it at “If we just redistribute a bit, if we just show our generosity a bit…” is to sell ourselves short, and actually to warp what the Bible tells us we should do. The Bible insists that something bigger is possible.

Here I also should point out that much of what our society calls “social-justice work” really just means building bigger charities. But other solutions exist. Slavery did not end in this country through acts of charity. Each individual slave owner did not free their individual slaves. A national movement had to fight to end slavery as an institution, and we see the same situation with poverty today. We can’t get ourselves out of poverty through charity, though to get ourselves out of poverty we need charitable acts along the way, to support this work we do — since of course people need food, of course people need housing. But believers can’t sell the Bible and God short by assuming that doing acts of charity gets you off the hook.

You said you don’t want to judge people, but this book does judge, doesn’t it? Or what might it have meant for Always with Us to present itself as providing the elusive social/economic agenda that a broad range of Christians long have been searching for, rather than as arguing that certain present-day Christian approaches are right and certain present-day Christian approaches are wrong? And I don’t mean now to assert my own moral judgment regarding your tone. I truly just want to know what in your lived experience makes such moral judgements valuable.

First, you’re right that my lived experience has produced this tone I write and speak in. That lived experience involves seeing people in the world’s richest country, at the richest moment in history, dying all the time from preventable causes — or seeing people living in raw sewage, seeing people go without water, seeing cities knowingly poisoning their people. We have to call all of that unacceptable. Over these years doing grassroots anti-poverty organization, it has become increasingly clear that we have to come out adamantly and say that we cannot accept people dying from exposure when we have the capacity to build pre-fab houses in 45 minutes, or dying from starvation when we throw away more food than it would ever take to feed the entire world. We cannot accept certain groups profiting off of someone else’s homelessness, or how corporations can end people’s livelihoods, or dig up ancestral burial grounds with no ramifications, with no judgement. I don’t mean to emphasize the judgement of an individual’s moral character, but the judgment of a society that accepts these circumstances. We have to call that wrong.

For years progressives and liberals, especially in the religious world, have tried to avoid addressing concepts of judgment. But I’d rather distinguish between judging individuals and judging society. I don’t read Biblical stories as emphasizing individuals. I read these stories as emphasizing social groups. The Bible doesn’t teach us how one person should act, compared to another. It teaches us how we should organize society as a whole. That all comes out of who wrote these stories, and why. These stories don’t call for punishment. They call for a proper account of social wrongs. And they do draw a line in the sand where it says: “If you trample on people, if you degrade the dignity of human beings and of life, then that cannot stand.”

Progressives and liberals often seem willing to say: “We stand against this — this is not OK. ”But when it comes to this question about how to hold institutions and society to account, people start getting nervous. Still, my lived experience suggests that this kind of hesitation doesn’t work. We contradict ourselves when we call some specific actions wrong but then refuse to judge the broader social situation. And making individuals feel guilty actually doesn’t accomplish anything. In my experience, if you organize people based on their guilt, you don’t get anywhere and don’t win anything. So we don’t want individuals begging for forgiveness. We want people to recognize right and wrong, to see when institutions or ideas degrade and dehumanize, to call out what is not OK. Those cries will reach the ear of God. And then it’s not always for us as humans or for me as an individual to say: “Watch me fix this.” But first we need some calling to account. And then people coming together to fix it together.

This calling to account might sound quite unsettling to some. But given your ongoing work amid one of the world’s longest-surviving social institutions, what most positive aspects of preserving established institutions have you also come to recognize? Where in your practice, your theology, your aspirations do movements and institutions meet? Could we ever truly enact the revolution your book sometimes calls for and bring Christianity along with it? Or given your conception of Jesus as a messiah among messiahs, would you in fact potentially embrace “a complete disruption of the economic order” that ended up destroying Christianity as we know it?

Maybe it’s just a question of semantics, but I do still identify as a Christian. I’m ordained to the ministry. I have a PhD in the Bible. I teach the Bible everywhere I go. So I wouldn’t say that I embrace destroying Christianity as we know it, but instead bringing Christianity back to its proper goals — which means changing and challenging a lot of who and what gets heard, which means showing what’s at the moral center of Christianity. I have no problem with radical changes and ruptures. But I’d place these in a broader ongoing theological battle. People in power always have used religion to say slaves must obey their masters, the poor will always be with you, if you do not work you shall not eat. So on one side this theological battle has justified inequality, inequity, deprivation.

But on the other side, throughout history people have taken up their faith, in this case Christianity, to fight for justice. Harriet “Moses” Tubman understood the Underground Railroad as a theological, Christian project. Frederick Douglass participated in all of these public debates about religion. So to throw out all of Christianity would mean to throw out these stories of struggle among liberationists. Those struggles always have existed, just as much as this slaveholder religion always has existed. We need to tap that prophetic tradition in Christian culture and worldwide in other religious traditions, because that’s where we can stand on the shoulders of those who came before us and see what right way they have paved.

So I wouldn’t call for throwing everything out and starting anew, but for building on what other people have built before. I have no problem with challenging the so-called Christianity of Christian nationalists that is dominant today in our politics, our country, our world. But I also don’t want to give them the power to define Christianity. The Greek word evangelia, out of which “evangelical” comes, means bringing good news (evangelian) to those (the ptochos) made poor by systems of exploitation. I’m not willing to give that up. I’m not willing to cede that territory because, again, the Bible’s good news, its Gospels, talk about folks, including Jesus, freeing the captives, releasing the slaves, letting the oppressed go free. The Gospels proclaim a year of economic abundance for all. We need to get back to that prophetic tradition and that moral center of our faith traditions. By doing so, we can and will change the way we live right now.