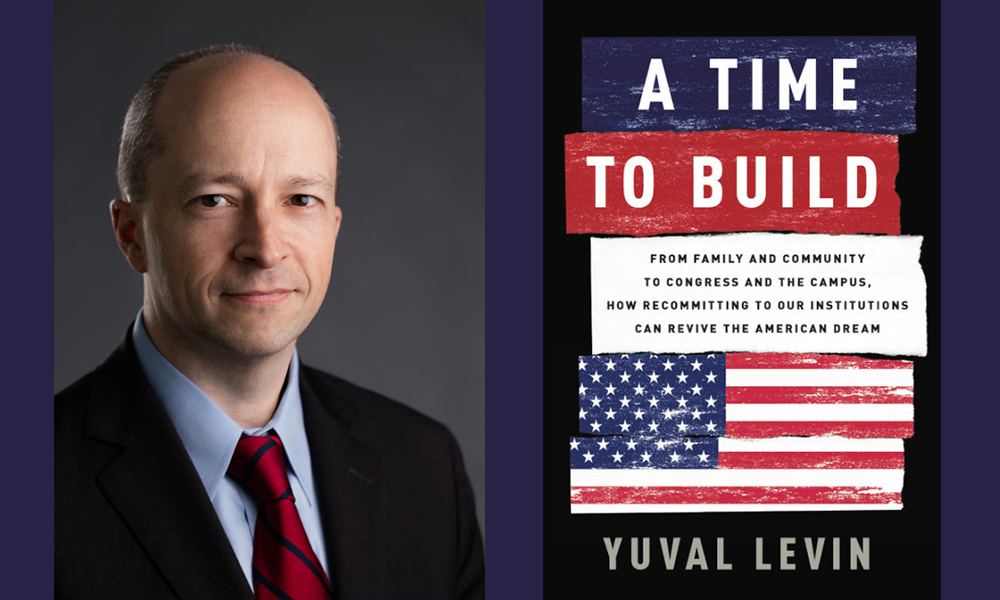

When do we lose trust in an institution (or in all institutions)? When and why do institutions stop producing trustworthy people? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Yuval Levin. This present conversation focuses on Levin’s book A Time to Build: From Family and Community to Congress and the Campus, How Recommitting to Our Institutions Can Revive the American Dream. Levin is director of social, cultural, and constitutional studies at the American Enterprise Institute, and the editor of National Affairs. A former member of the White House domestic policy staff under George W. Bush, his previous books include The Fractured Republic and The Great Debate.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could you first sketch one or two clearest indications of us living through a social crisis we haven’t yet figured out how to acknowledge or discuss? Which particular cultural trends or public events or personal reflections crystallized for you this book’s driving questions of: “What does the missing thing look like? What is the nature of the deficiency we feel? What would it take to fill the gap?”

YUVAL LEVIN: This book really does begin from that sense of us living through a collective crisis we’re having trouble recognizing or describing — a crisis expressing itself through intense polarization and dysfunction in American politics, through the kinds of hostility and cultural combat we see on college campuses, and also in parts of American religious life. But then even more, in the personal lives of individual Americans, we see this sense of isolation and alienation contributing to rising suicide rates, and to the opioid epidemic. These problems are linked, but in less than obvious ways.

Our society tends to diagnose problems like these first by asking questions about individual well-being: how’s the economy doing? How about people’s health or safety? But the problems we face now aren’t in that realm. They arise in the realm of our sociality, of how we live together. Even when we ask about sociality, though, we still incline towards a pretty individualist way of approaching these questions. We still imagine American life as this big open space full of autonomous individuals having trouble connecting, so we talk about how to build bridges, how to break down walls. But that ignores the basic need for structure in our social life, for forms and modes of organization that draw us in and bring us together.

So I argue in this book that if we want to picture American life as this big open space, we need to see that space as not just filled with individuals but also filled with structures, with institutions. And a lot of this breakdown we’re living through is a breakdown of institutions. Focusing on institutions won’t magically allow us to understand the totality of our social crisis. But it will help us to understand some important pieces that we as Americans tend to miss or ignore.

Given that some of these most potent interpersonal dynamics remain far from obvious, and perhaps especially difficult for contemporary social-science metrics to track, how can we begin to clarify which felt absences of belonging, of cooperative sociality, of legitimate authority, to consider symptoms, and which to consider causes, of the broader malaise you describe? For example, in your account, where might populist political tendencies today provide the explicit expression of a galvanized electorate, and where an unrecognized plea for something this electorate itself never names — something less like the abolishment of prevailing norms and institutions, and more like a restored sense of their earned integrity?

First I don’t want to claim to understand anybody better than they understand themselves. I definitely don’t. But I do think that when we ask these questions about the state of our society, we have to think a bit like a physician. When someone suffering from fatigue comes to a doctor, the doctor doesn’t just say: “Well, you need to sleep more.” That might factor into the doctor’s recommendation. But he or she also will try to determine, for example, if this patient has an iron deficiency. Of course this patient will never complain about lacking iron. But based on some knowledge of how the human creature works, the physician might have an idea of deeper causes for this kind of problem. Similarly, when we hear ourselves complaining about our politics, we need to ask ourselves what else we might be missing, beyond what we are calling for.

In this populist moment, we might hear calls for liberation from the corrupt and oppressive elites. But we should wonder whether this particular call also suggests a desire for more legitimate social and political institutions — institutions we can respect, and trust, and align ourselves with, and which deserve our loyalty. Once you consider that possibility, you start to hear in certain populist claims less a concern about our elites being too strong, and more about them being pathetic. You start to hear less a demand to tear down corrupt establishments, and more a call to build up legitimate establishments. I titled this book A Time To Build because I do sense, just beneath this political rhetoric about tearing everything down, a strong public desire, and in any case a need, to try to solve many of today’s most pressing social problems by constructing and reconstructing institutions.

Here we probably should introduce this book’s working definition for institutions, prioritizing durable structures (whether legal or normative, bureaucratic or interpersonal) operating as crucial intermediaries between our inner experience and our public lives — molding identities to fit within a designated group’s task-oriented constraints, and enabling a broader flourishing by cultivating capacities both for individual and collective action. Especially within a contemporary US culture believing itself to esteem immediacy, informality, authenticity above all other civic virtues, why did it seem salient to foreground thinking about institutions in terms of this enabling/constraining dynamic? Where do we (both on the political right and left) most conspicuously undervalue our ongoing reliance on institutions, particularly on these grounds?

Right, I define institutions as “the durable forms of our common life.” They’re the structures for what we do together — consisting of individuals, but shaped by common aims, and in turn shaping common efforts toward those aims. That formative character, that way institutions shape us, is really crucial to what they are and do. But that’s something we tend to miss, or to dismiss, because of this longstanding tendency in our culture to undervalue institutional mediation. Because we tend to emphasize directness and a sense of authenticity, we sometimes need reminding of the crucial role that institutions play not just in shaping society, but in shaping us.

In one sense Americans, both on the left and right, always have been great institution-builders. Particularly outside of our politics, we tend to respond to social problems by building institutions. But we almost can’t help undervaluing our institutions, and understating (especially when they’re functioning properly) what these institutions do. Successful social institutions basically become the air we breathe. We see right through them, except when something goes wrong. When that does happen, we need help to step back and consider what went wrong — because again we tend to overlook the supportive role that institutions play in our public life.

So in this book I really try to bring to the surface how our institutions should work, and where they need fixing right now. I also try to stress that prioritizing social institutions always remains a matter of degree. Institutions certainly can become an oppressive force in our national life. That happens. I consider, for example, mid-20th-century Americans to have been, in some important ways, overly trusting of their institutions. Coming out of World War Two and the Depression, we just thought we needed these massive institutional forces (big government, big labor, big business) to run the country. We had amazing trust in them. I’d say too much trust. But now we’ve reached a point of having far too little trust in social institutions so important to our basic functioning. We need reminders of what these institutions do for us, and of how they work. And as you suggested, we especially need a better sense of how institutions form us and empower us through constraints — again even in a society that we tend to think of as very free and very liberal.

When we do think about institutions now, we tend to think in terms of our loss of trust in them. That decline in trust is very easy to show in public-opinion data. But again, this should cause us to ask ourselves: “What does it mean to trust an institution?” And the answer has a lot to do with the formative work of institutions. I’d say we ultimately trust an institution when we believe that it tends to form trustworthy people. Every properly functioning institution coaxes its members to participate in a reliable and responsible way, which helps the rest of us to trust this institution and the people within it and its expertise and its products.

When we lose trust in an institution, this often starts with us sensing that the institution no longer produces trustworthy people. This could just come from familiar forms of corruption, with people using institutional power to advance their own will or interest over others. But that doesn’t quite explain the distinct loss of trust that defines our own time. The distinct loss of trust you see today suggests that our institutions have started failing (or have stopped trying) to be formative. In one institution after another, you find people using institutions performatively instead — using them as stages to perform on, to build their own brand.

Yeah here I’d start from your point that we don’t just see increased distrust in any single institution at present, but in all institutions — suggesting not just some individualized corruption or incompetence, but broader cultural confusions over how and why institutions operate. I’d bring in your incisive characterizations of insiders abusing institutional authority, of supposed outsiders preferring to present themselves as “above the fray,” of personal celebrity overshadowing professional integrity, and of pervasive polarization distracting institutional players from fulfilling their distinct social functions. So for one concrete comparative example of how two prominent federal institutions have fared in preserving capacities to mold participants’ behavior, and to engender a sense of public legitimacy, could we contrast the trajectories of Congress and of the federal judiciary?

Congress in many ways has become a performative institution. Members now tend to think of Congress as a platform for building their own personal brands, for becoming more prominent in popular culture, for getting a better time slot on cable news or talk radio, for gaining a bigger social-media following. Rather than seek a microphone to acquire power in order to advance social change, they seek power to get a microphone and then to call for social change. That shift in emphasis makes for a big difference. It means that Congressional members (and increasingly the rest of us) now think of this institution as a stage for some kind of performance art channeling public frustration — rather than as a governing body designed to negotiate differences, find accommodations, pass laws. Of course we see something similar in the Trump presidency. Donald Trump has almost exclusively been a performative president. He has very little sense of the executive branch’s actual role in our system of government. He basically just sees a big stage for a reality-television show of the type he has starred in his entire adult life.

But in terms of a broader loss of trust in our governing institutions, Congress certainly has the least trust of all. Polls tend to put public confidence in Congress down as far as a single digit, or very low double digits. The courts, as you suggest, have retained somewhat more public trust, I suspect thanks to their resistance to some of these corrosive institutional trends. The courts have not turned themselves into performative spaces. They still staunchly resist putting cameras, for example, in most federal proceedings. The Supreme Court has always resisted oral arguments becoming TV shows. They’ve reserved some private spaces for real deliberation. Federal court decisions also still get made in closed conferences of judges — who can talk to each other, negotiate sometimes, help each other understand the various points of view. As a result, the public still finds it easier to trust our judiciary. A judge still appears to us as a certain kind of human type (and not just as another actor in our political or culture wars).

And among our most trusted federal institutions, we also could consider the military. We trust the military not only because it tends to do well protecting our country (though it does), but because of its unabashedly formative institutional culture. The military takes men and women and turns them into soldiers, sailors, or Marines in ways that clearly change these people and that subject them to an exacting code of integrity. So I also do still see gradations in public perceptions of our institutions, and I’d put the military at the more successful end of the spectrum.

Now for one less codified, yet equally vital civic institution, could we consider how journalism likewise has suffered a significant loss in public credibility: again in no small part, your book claims, due to its transformation from a mold institution to a platform institution, here exacerbating a generational divide in behavioral norms within the industry itself, blurring distinctions between professional and highly personalized engagements — all in ways that confuse and/or alienate many audiences? And how does the inner life of such a complex civic/commercial/technological institution also get shaped by external forces (in this case, for example, tech-driven market concentration)?

Right, in this book journalism appears as an example of a profession. The professions themselves are distinctly formative institutions. “Accountants” and “doctors” and “journalists” exist as professional types in the world, because institutions have formed these people by subjecting them to certain norms and rules and practices that make them more trustworthy. We trust what scientists tell us (though, of course, less today than in preceding generations) because they operate through a method that allows them to root out error, and to recognize the limits of their own knowledge. Journalism in many ways tries to follow a similar model, and to say: “Before we state or write something, we put it through an exacting process and verify it to the best of our abilities. What we say differs from what just anybody says. We’ve checked our sources and performed our due diligence.”

For all of these reasons, journalism can claim a certain authority and public trust. But journalism nonetheless has gone through this same process of its institutional inner life getting corroded by a more performative ethic: with many members neglecting the institution’s formative aspects, stepping out from their newsrooms and layers of editing, operating as individuals on Twitter and other social media especially, or on cable news, blurring their reporting and the expression of their personal views in ways hard to tell apart, making it difficult as you said for many people to see the distinct added value of what journalism provides. If you look at Twitter, you find a bunch of reporters basically de-professionalizing themselves, building their own brand, leveraging the authority that the institution gives them — just to promote their own personal profile.

Now, journalists do all of this today for reasons very easy to understand. Enormous economic and career pressures push them to build up their personal profiles. And similarly, even while journalistic enterprises face these institutional dilemmas, even though Twitter de-professionalizes the New York Times, it also drives a huge amount of traffic to the Times. So these journalistic institutions, likewise operating under intense market pressures, see huge value in encouraging a reporter to circulate widely. This book aims in part to make the costs of that approach a little more apparent.

Again in terms of what institutions do, it also seems crucial to bring in your admittedly partisan orientation as a conservative, a conservative perhaps disappointed by certain aspects of present-day Republican Party politics, but nonetheless compelled by a conception of humans as flawed, crooked creatures forever requiring the kinds of moral and social formation that institutions provide. So where might you see it as inevitable that the burden for calling on us to re-fortify our institutions falls on the avowedly conservative party, say in a Burkeian vein? Where do you see a post-Reagan Republican Party (often emphatically skeptical of government intervention) as protecting and preserving threatened private institutions, and where as contributing to the problematic devaluation of our public institutions’ authority and expertise?

I understand conservatism as inherently protective of core institutions. Conservativism begins from this premise that human beings start out imperfect (fallen, you might say), and need to be formed before they can become free. We have institutions because we need this kind of formation. Our family and community and religious and educational and political institutions do just that. So I see conservatives as striving to protect our core institutions — with progressives, at least those who would emphasize a politics of liberation, more naturally hostile to certain kinds of institutions (while also, of course, relying on and building on others).

But in our politics today, those divisions have become much less clear. We now have an anti-institutional right in American politics, not just a populist right. In the age of Trump, we have an even more explicit hostility directed at our institutions — treating them all as rigged against the public. So again as a conservative, many of these attacks from the right on our institutions really do concern me. Another main purpose for this book involves trying to remind conservatives why we start from this premise that society needs to perpetually build and rebuild institutional forms that can in fact liberate people, both by molding and constraining them.

I also do hope that certain elements of this argument can resonate among people on the left, since we all believe in a free society, we all believe in basic rights, we all believe in protecting vulnerable people — and ultimately you do need institutions for all of that. Populists both on the left and right find it easy to assert that institutions just protect the powerful and reinforce the status quo. Certainly institutions can do that. But our society’s most vulnerable members often have the biggest need for strong and vibrant institutions. People who already possess an abundance of economic and social and human capital can make their way, even when our institutions break down. But we need functional institutions to help disadvantaged people build up this capital, especially social capital. We need institutions to protect their rights and to help them build the networks and habits and skills to thrive in our society.

A lot of the complaints our culture makes against institutions are justified. And yet we still need strong, functional institutions. That’s why complaining can’t be the end of the story.

Progressing through your book, it did become much easier to conceive of proper institutional functioning producing a virtuous normative cycle — with refocused institutions, appropriately shaping their participants’ behavior, in turn reviving public faith in these institutions. Here I can begin to unpack your quite useful conception of what it might look like for our politics to conceive of genuine social reform as ultimately stemming from personal formation. But, of course as with the virtuous cycles of public and private flourishing sketched in Plato’s Republic, how do we present imperfect beings, finding ourselves amid flawed social structures, first break out from such compromised circumstances? Returning to the topic of tech concentration, for example, what role does regulating market concentration (and any corresponding institutional capture) play during a time to build? Or who specifically should rebuild our institutions? What kind of robust public (presumably governmental) presence might we also need right now if we ever hope for a virtuous institutional cycle to establish itself?

Well again, institutions exist at every level of our lives, from the family and the community all the way up to national government. Everybody participates in institutions at some level, right? So you could consider that both good news and bad news. It’s bad news in the sense that when we reach a point of broad-based corruption or deformation of our institutions, we face what can feel like an all-encompassing and insurmountable problem. But it’s good news in the sense that each of us has an important role to play, and an important contribution to make. By thinking about what institutions do, we also can recognize what we each individually might do. We can begin (though only begin) by asking ourselves: “Given the institutional role I have, what should I do in this situation?” When you face a choice or judgment, you can ask yourself (as a parent or teacher or vice principal of the school, or CEO or worker, or member of Congress or voter): “What institutional responsibilities do I have?” Asking this question a little more emphatically in our everyday lives can make a much bigger difference than we imagine.

The people who most anger us today tend to be those who fail to ask themselves these questions in situations where they obviously should. The people we tend to respect probably do ask these questions. So I would consider that a necessary beginning, because in order for institutional reform and rebuilding to happen, people within our existing institutions need to want it to happen. People already serving in (or at least served well by) our institutions will need to change, and to want to change.

But I also do see room for systemic institutional reform, some of which clearly would have to start with political and governmental interventions. We need to reform how Congress works. We need to rethink how to regulate our economy. Current concentrations of power in some of our key markets prevent the proper formation and function of institutions. Today, if you find fault with the character of our social-media giants, for example, you can’t just start a rival model with a realistic chance of competing — in large part because of concentrated economic power. So I do see combating certain kinds of concentrations as one significant way to stimulate institution-building and -rebuilding.

But I wouldn’t focus solely on that approach. One basic argument in this book is that none of us can just think about institution-building as somebody else’s work. Each of us has some work to do. Each of us, no matter where we are in our lives, has the potential to make a positive difference. And then we also do need to push for broader changes that can harness these positive contributions on a society-wide scale.

Many progressive LARB readers might bring a deep skepticism to any call for shoring up institutions that seek to mold us and to facilitate some supposed consensus-based unity — not necessarily because such readers prefer to promote the liberated individual above all else, but because they recognize both normative and legal institutions as complicit in countless unjust social outcomes past and present. So in what ways does re-strengthening today’s institutions overlap with critiquing past limitations and hypocrisies (again not to categorically deny the value of institution-building, but to foreground an ever-present need to keep refining the conceptual foundations and the concrete implementation of even our best institutional frameworks)?

That question makes a lot of sense to me. Institutional reform has to include, at some level, a critical process, where we hold up our institutions to their own standards, and force them to see their own failings and hypocrisies. We can’t just cynically set aside these ideals, and assume everybody simply serves their own interests. We should maintain institutional standards, in ways that really make each of us feel ashamed when we fail to live up to our own professed ideals. That powerful form of social change only happens when we take our institutional ideals seriously. Genuine institutional reform does involve us saying, for example: “Okay, if we believe in equality, then we need to make big changes.”

Similarly, rather than just treat our politics as a battlefield, where we tend to presume the moral failings of people we disagree with, and to feel justified in trying to destroy them, we need to respect each other’s ideals and to hold each other to them. We need to approach each other by sometimes pointing out: “You said you believed in this, yet your actions suggest the opposite.” We shouldn’t just assume that no one really believes what they say. One thing I’ve learned working in and around politics for some time (working for a president, for a Speaker of the House, and others) is that basically everyone in our politics believes they are acting morally and advancing the good. There are very few genuine cynics. I know that’s hard for people outside Washington to accept, but it is undeniable. So although cynicism can sometimes seem sophisticated and worldly, it’s actually quite naive.

Codes of professional conduct likewise play a critical role in this book. So how to apply that model of professional decorum to a broader democratic context in which by far the majority of workers do not operate as professionals? What equivalent normative codes stand out for their potential to keep constructively molding us throughout our adult lives? When, for instance, should progressives recognize military and religious institutions as providing crucial, morally grounding channels for civic flourishing? When should conservatives see union-busting policies as culturally (and ultimately economically) corrosive, in terms of further depleting social capital, often among those who need it most?

Thanks for that question. Arguing in institutional terms can seem like arguing on morally neutral grounds. But I do want to advocate here for the legitimacy of acting on our deepest moral priorities, and for giving each other the room to do that.

Our society has always had to contend with this basic fact of its own moral diversity. Not everybody agrees on fundamental questions. Historically, we’ve dealt with these differences by trying to establish some basic ground rules, rooted in ideals which hopefully we do all share. These defining ideals of our democracy (federalism, the insistence on everybody having equal rights, equal treatment under the law, free speech and expression and association) suggest that, in order for me to live a moral life as I understand it, I also need to make room for other people to live moral lives as they understand them — even when we don’t entirely share the same understandings. One of our biggest and most enduring challenges living in a free society comes from this basic need to recognize our disagreements (sometimes reflected in our different institutional affiliations), without therefore trying to win the argument by destroying each other’s institutions. Civility in a free society like ours hinges on the shared premise that the people we disagree with are not going away. We thankfully have no process to make them just disappear. So the question becomes: how do we establish some basic rules and structures that allow all of us to lead good lives and help our children flourish?

Obviously, even asking the question that way requires a certain kind of democratic sophistication. And I believe that our institutions exist in part to instill in us this kind of sophistication. When we lose this sense, when we assume our politics can only function as some struggle to the death requiring us to assault other people’s institutions, when we decide that the best way to fight the left is to destroy the university, or that the best way to fight the right is to destroy religious freedom, we start abandoning the basic, necessary underpinnings of life in a free society.

So I hope for this book to make the point that most of our institutions exist to advance some idea of the good. Of course we can’t say that about every institution. The mob is an institution, with a strongly formative ethic. And our society should try to destroy that particular institution. So we do have to make some very basic distinctions, after all. But generally speaking, to provide conditions by which many different people can live worthy lives as they understand them, we do need a broader shared respect for properly functioning institutions. And this does include, as you suggested, appreciating the role of institutions operating from economic or political or cultural premises with which we might strongly disagree.

I consider unions, for example, enormously important in helping working people (who often don’t have much economic power or cultural leverage in our society) to build up social capital. I might differ from union leaders on certain economic analyses or political priorities, but I can fundamentally respect what unions do, and can see how they contribute to an institutional framework allowing for robust economic competition. Similarly, I’d love for Americans skeptical of religious institutions nonetheless to recognize the value in all of us building institutions around our own most closely held priorities. Attacks on religious liberty are assaults on the ability of your fellow citizens to pursue the deepest truths about our world, and to live moral, upright lives. We all should reject such assaults.

Turning then to academic institutions, I will acknowledge that, even as a progressive professor, I don’t have much to disagree with in your account of a distressingly constrictive academic monoculture: as manifest not just through sensational stories of students shouting down certain invited speakers, but in everyday professional workplace dynamics — and as perhaps driven by blanket moralizing administrative agendas even more than by particularly vocal students or teachers. I likewise can appreciate your accounts of a moral-activist strain in American academic life misidentifying itself as iconoclastic and emancipatory long after it has become quite dominant. Within that contemporary context, could you flesh out why you might consider it crucial for educational institutions to rekindle an emphasis upon character-molding (stressing both an ethic of interpersonal responsibility, and of disciplinary restraint), in part to help shore up their own credibility among a broader public?

Yeah, I’ll start with the university’s distinct institutional function in a society like ours. The university has a huge role to play in forming the elite of American society (with “the elite” broadly understood: not the top one percent, but say the top 35 percent). The university always has played a somewhat controversial role, and has long had its own competing subcultures: with some focused on building skills, and some on social activism, and some on more fundamental critical reflection. I actually consider social activism one of the oldest and most consistent forces in American academic culture. Harvard and Yale were founded to help provide a moral framework for American society.

The tensions among these subcultures (under an overarching academic culture devoted to teaching and learning) are not new. But we do now see a new kind of disorder in that overarching culture, especially as the result of changes in universities’ administrative culture. Many universities have lost sight of the importance of teaching and learning as their institutional mission. When you turn social activism into an administrative language and a mode of institutional operation, you close off some spaces necessary for pursuing truth. And ultimately, the way to push back against this kind of institutional deformation, I believe, is for academics on all sides of our so-called culture wars to insist on the case for the university as a place of teaching and learning.

The right, I think, misses this sometimes when we argue for free speech as the defining principle of academic freedom. Academic freedom sometimes differs from free speech. The university does not just offer yet another stage on which to stand and yell. Its purpose is to pursue the truth through teaching and learning.

The left, I believe, oversteps when it argues that it ought to own university culture, as a space to advance its culture-war agenda. Again, that just doesn’t leave enough room for teaching and learning. And here I don’t mean to focus on those extreme and very rare examples of speakers shut down in some violent way. I mean to focus on a deeper problem evident in hiring and promotion practices, where a particular echo chamber reinforces itself along with an understanding that being a proper academic means holding certain political and cultural views — rather than having particular areas of expertise as a researcher or teacher. So I do point to the need for some serious soul-searching within the university, specifically about how to expose students to a broader range of ideas: not simply for the sake of diversity, but for the sake of active and ongoing truth-seeking.

Protecting that overarching academic ethic requires there to be, within the academy, a party of the university that isn’t just another participant in our broader culture wars, and that cuts across those divides and makes the integrity of the institution itself the priority.

Well finally then, what could our civic culture look like today if operating from the basic principle of devotion, with each of us unabashedly committing ourselves to a higher ordering principle — as harnessed through an institution to which we belong, an institution shaping us into being its own proper builders?

Right, I close the book by thinking about institutional commitments through this lens of devotion, because I sense us searching for objects of devotion in contemporary American life. As we live through this moment that can feel quite cynical, that can feel like a constant bath in acid, I think a lot of Americans are seeking out ways to become less cynical, and to have less emotional distance from the things we care most about. So everybody now might feel the temptation to present themselves as an outsider. But I believe we still hunger to operate as insiders (at least somewhere). I think a civic culture encouraging that kind of institutional commitment could help us to be a bit less cynical, a bit less prone to emphasizing our differences and expressing our disagreements, a bit more inclined towards collectively solving problems.

I say “a bit” in each of these instances, because I’m talking about changes that are a matter of degree. I’m not talking about a dramatic social revolution. But I think a degree of added institutional devotion could bring about an enormously important and influential difference. To think of ourselves a bit more as insiders, to try to act a bit more through these institutions where we feel like insiders, could make a huge difference in how we conceive of our collective potential to address big social problems. Too often now we tend to despair of that potential. Our society has accomplished so much, and its institutions deserve better than this. They deserve a bit more of our devotion.