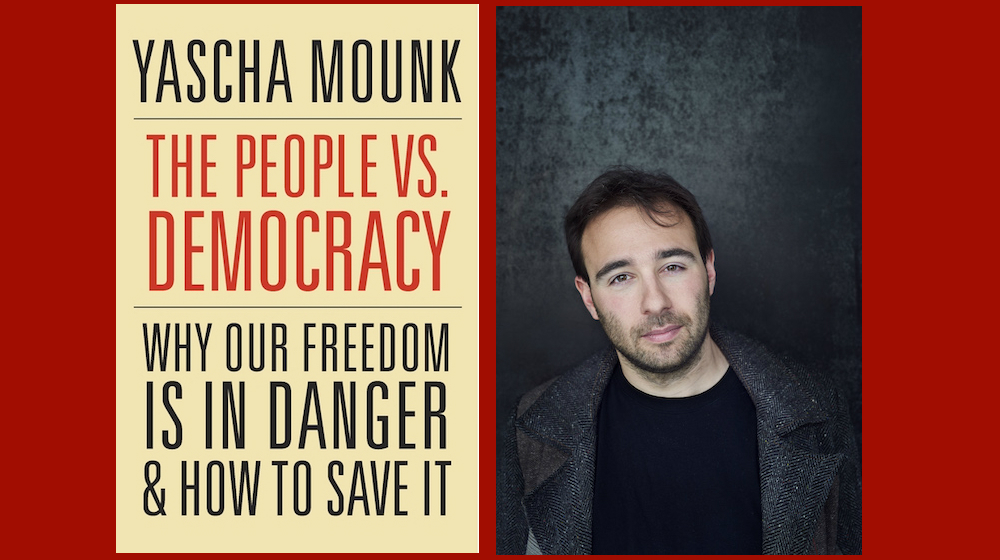

When do progressives fail to recognize populists’ most democratic tendencies? When do progressives themselves drift towards undemocratic and / or illiberal indifference to their fellow citizens’ views? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Yascha Mounk. This present conversation (transcribed by Christopher Raguz) focuses on Mounk’s book The People Vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save It. Mounk lectures on Government at Harvard University, and is a senior fellow in the Political Reform Program at New America. He is also author of The Age of Responsibility: Luck, Choice, and the Welfare State and of Stranger in My Own Country: A Jewish Family in Modern Germany, host of The Good Fight podcast, a columnist for Slate, and a regularly contributor to the New York Times, The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic, and Foreign Affairs.

¤

ANDY FITCH: I could read this book and wonder why, apart from your marketing team wanting a catchier title, you didn’t call it “The People Vs. Liberalism” — since that seems like the most perennial and also the most pressing current tension you address. I do appreciate, though, your book’s broader point that, over time, the erosion of liberal norms and institutions most likely eclipses prospects for democratic decision-making as well. So to start, could you outline some of the most basic complaints appearing on a global basis right now against undemocratic liberalism (in which rising social inequalities and increasingly technocratic regulatory mechanisms crowd out possibilities for ordinary citizens to help shape our collective fate), and some of the most ominous threats posed by democratic illiberalism (particularly when populist leaders, failing to deliver on extravagant promises, feel compelled to cast liberal institutions as roadblocks impeding the will of “the people”)?

YASCHA MOUNK: That clash between “the people” and liberal ideals and institutions definitely is central to this book. Populist uprisings across the world right now tend to direct themselves against the liberal parts of political systems: minority rights, the rule of law, and so on. We definitely see that in the United States at present. And we also see in present examples of consolidated populist power, whether in Turkey or Hungary or Venezuela, that once you’ve captured independent institutions (like the courts, the media), once you’ve cowed the opposition, then you’ve truly started to turn against democracy itself. That’s what makes illiberal democracy such a significant and such a troubling regime form right now. In most cases, it ends up opening the door to more straightforward dictatorship. So while voters supporting someone like Donald Trump might not see themselves as attacking democracy, supposed champions of “the people” ultimately end up doing just that.

In order to make sense of populism, we have to remember that our political system ties itself to certain key values, such as individual freedoms — the right to expression, the right to worship, the freedom to choose how to lead our private lives. In order to sustain that freedom, we need to protect the liberties even of those individuals who belong to unpopular minorities. We need to preserve the rule of law, and the separation of powers. And then we also at the same time need democracy run by the people. We need collective self-governance, in which we decide together on our shared fate, rather than having a dictator or monarch or priest or expert class make the important decisions for us.

But when I look around the world today, I see two elements of many liberal-democratic systems seeming to split apart. Countries in North America and Western Europe have, for the past 50 years, been comparatively good at protecting individual liberties and at sustaining the rule of law. At the same time, though, they’ve suffered from the pervasive influence of political spending on our legislatures. You see institutions like Congress with little concern for what “the people” actually want. Congress clearly backs what big donors want, and conservatives seem quite happy with this arrangement. So that’s a form of undemocratic liberalism.

You might approve or disapprove of decisions these institutions make, but in any case these institutions end up taking decision-making power away from the people they supposedly represent. Again, when properly coordinated, these institutions play a crucial role in our liberal democracy. But when that overall liberal-democratic balance starts breaking down in certain places, then voters begin to feel that their voices don’t matter. And that widespread feeling easily can give rise to what I call illiberal democracy, or democracy without rights. Populists then can blame all of our problems on an out-of-touch political elite. They can tell voters that we need to get rid of this elite, to restore a bit more power to the people. But once these populists start to erode liberal elements of the political system (again: minority rights, the rule of law, and so on), this easily can degenerate into straightforward dictatorship.

Here in terms of addressing present-day U.S. scenarios, I’ll try to sketch one concrete analogy to some broader populist trends you just traced. Let’s say I were to call a white middle-class person from my parents’ generation a “racist.” Let’s say this person defines a “racist” as most middle-class white people did a generation prior: as an overt, often impassioned advocate for white supremacy. This person I just called a racist knows, quite intimately and quite accurately, that he / she doesn’t fit that definition. So regardless of whatever deeper, systemic, institutional critique I had meant to imply, my accusation doesn’t stick. Semantic snags keep us from engaging in constructive conversation. We just end up further polarized, now fueled by overly personal frustration. And here, by comparison, let’s say I call a Trump-supporting populist “anti-democratic.” Let’s say this person does a relatively sincere scan of his / her internal motivations and, again, my accusation doesn’t stick. This person can feel, quite palpably, his / her own commitment to democratic self-governance — particularly in the face of intrusive overreach (my ungrounded accusation, for example). Here your book seems to make one of its most pointed interventions, by suggesting that we need to engage with populists, we need to hold populists accountable, not by criticizing their supposedly retrograde personal character and internal motivations, but by responding: “If you are the democrat you say you are, then consider these likely anti-democratic consequences to your populist approach.”

That’s a helpful way of putting it. One big problem with how we talk about politics at present, especially on social media, comes from trying to describe somebody else’s behavior in terms of an “-ism,” and inevitably assuming evil motives. If someone disagrees with us on some cultural controversy of the moment, then they might be a white supremacist or they must at least have bad intentions. But once you’ve impugned people and their motives this way, you can’t expect them to remain open to persuasion. The conversation ends, and you just begin shouting at each other — either through Facebook posts or, in your family example, across the dinner table.

But if you can keep this discussion focused on the effects that certain types of political behavior will bring, then you don’t need to impugn anybody’s intentions, and people will be more likely to listen. You could ask: “Hey dad, why was everybody at that gathering white? Does that happen because you went to certain schools, or because you’ve made certain types of friends or found certain types of business partners? Does it seem unfair that other people didn’t make it into your circle? Does that feel limiting to you in any way?” And maybe your dad can listen to that, and think about that, and can answer in ways that challenge your own assumptions as well.

So I do wonder a lot about how to talk to people who embrace populist politics. I sense that we still actually support many of the same ideals. I don’t want to disrespect them or undermine them, but I also don’t want to understate the fact that racialized coalitions quite often have bad intentions, and produce noxious and truly harmful effects. At the same time, I can understand why voters attracted to populism might believe that nobody listens to them, and that power needs to be returned to the people. And I do think that we provide the best counterargument to illiberal democracy when we point to the numerous countries who elected populist leaders and ended up with dictators. Those examples can help to make the persuasive case that if you really do care about democracy, if you really don’t want to swap one semi-unresponsive political class for some strongman who doesn’t respond at all, then you should think through the consequences of populist politics.

In the end, in a democracy, we all have to remain open to persuasion in this way. We all have to recognize that just because we voted for somebody in the last election doesn’t mean we need to vote for this same person in the next election. And specifically with Trump voters, I would ask them to consider how he has violated so many of our shared principles, and how his economic policies have hurt many of his supporters much more than they have helped.

Have you found traction with this approach among right-leaning, conservative, even populist readers? Of course many books about populism have come out recently. Has yours appealed to certain audiences potentially sympathetic to (or at least opportunistically aligned with) Trump?

I can’t tell. I did do an extensive book tour, in part because it felt very important to me to take this message not just to New York, Boston, and Washington, but to Ohio, Indiana, and Utah. But of course it turns out that, wherever you go in the U.S., when you show up at a lovely bookstore, the people you tend to talk to are just as politically informed and left-leaning as readers in San Francisco. So hopefully I have reached some Trump supporters along the way, but I do feel quite skeptical that I’ve convinced them I’m right [Laughter]. At least I can help to orient people who do want to stop populism, and help them to understand how we might also need to change our own thinking in order to better protect our democracy.

Well here to take a step back, and to consider some of this book’s orientational (at times convention-flouting) assumptions, could we start with your claim that liberal democracy’s consolidation does not guarantee perpetual social progress along some one-way street? Your book instead suggests that liberalism and democracy might both be necessary to help secure and stabilize each other, but that their combination does not in itself sufficiently and inevitably ward off any destructive threat (internal as much as external) that might come along. And let’s say we perceive in Trump’s election a rhetorical swing away from certain forms of undemocratic liberalism, and let’s say we can imagine a subsequent swing away from Trump’s populist illiberalism then going too far in the opposite direction — perhaps reassuring us with its claims to pursue equality for all, but posing new dangers to democratic rule as it disregards concerns for individual liberty. Could you provide some of the closest, most instructive historical comparisons in which this type of increasingly polarized oscillation does in fact devolve into seemingly existential conflict, or any examples of societies successfully de-escalating this downward spiral towards destructive partisan clash and / or authoritarian rule?

Historical analogies do work best here to show us the long-term consequences. We can look at self-governing republics that remained relatively stable for centuries, and then started to polarize more deeply until they suffered slow, painful deaths — like the Roman Republic. Or for a shorter timeline, we can look at populists around the world right now who sound strikingly similar to Trump. In many cases, these populists have managed to consolidate power quite quickly.

For either type of comparison, though, I wanted to avoid the classic foreign-policy pattern of the generals who always end up fighting the previous war. And you never can make a simple, straightforward comparison between one time and place or another. So here we should think of the United States as the oldest and most affluent modern democracy ever to experience a populist uprising. Even as certain striking comparisons to other populist uprisings do stand out, we need to factor in that the U.S. has a strong liberal-democratic tradition. We have a vibrant civil society. We have significant independence for corporations and public institutions.

Of course you still can find plenty examples of a society that starts with a certain degree of consensus over the most fundamental questions, but also some basic disagreements over how the political system should function. Many societies like that eventually do break down, like in ancient Athens and ancient Rome. And some younger democratic European states failed in the 1920s, and some newly independent African states broke down quickly after decolonization. So we easily can offer historical examples of collapse, but finding examples where countries came back together again is a lot harder. Extreme polarization tends to lead to civil war, rather than to de-escalation. In the wake of catastrophe, a new stronger consensus might emerge, as in the U.S. after its Civil War, or Germany after World War II. But we do have to recognize right now the need to form a new consensus, a new way of overcoming deep partisanship and polarization, a way that doesn’t necessitate going through catastrophe — even if we don’t have many historical examples to draw upon.

In terms of present-day polarities, and in terms of the most likely causal sequence by which democratic illiberalism transforms into undemocratic illiberalism, your book demonstrates how populists attack those liberal institutions that seem to deny “the people” their right to exert a moral monopoly, with “the people” perhaps first defined in majoritarian distinction to various minority groups, but with “the people” then defined increasingly narrowly, until we really just mean the whims of a tyrannical ruler. Where along that trajectory (or more broadly, where alongside this book’s primary topics of democracy and liberalism) might you place present-day tribalism? When we critique “populism,” when do we mean to focus on negative aspects of exclusionary tribalism? And perhaps in distinction to tribalism’s more corrosive aspects, what might an “inclusive patriotism,” still affirming the nation state, but in much more multicultural terms, look like?

First I’d point out that you can have distinct political tribes which nevertheless recognize each other as legitimate. In many postwar societies, for example, you had socio-cultural divisions between left and right, with the left rooted in working-class culture and the right advocating bourgeois interests. These cultural divisions ran very deep — with say a worker who was part of a trade union and voting social democrat in 1960s Stockholm having relatively little in common with a small-town lawyer who was quite religious and voting conservative. But you didn’t see these different camps publicly try to delegitimate the other side. They might have competed and clashed with great intensity, but they both still recognized each other as a legitimate alternative to their own position.

Political conflict becomes much more problematic when one side says: “I just can’t take the other side seriously. I just can’t trust them. I actually loathe them and what they stand for.” In order for this kind of loathing to become a common public feeling, you typically need a demagogue who weaponizes dislike of the opposition into a powerful political force. And again it does seem to me that these circumstances have come about rather quickly in the contemporary United States. The actual degree of ideological partisanship probably hasn’t increased much over the past few years, but the ability to acknowledge the presence of legitimate citizens on the other side has dropped drastically.

And look, I grew up as the child of a Polish Jew who had left for Germany. I studied in England, and lived for stretches in Italy and France before coming to the United States, so the idea of leaving behind nationalism, the idea that we should move beyond those types of local allegiances, has obvious appeal. But when I look back at the last 20 or so years, I also can’t help noticing that nationalism has remained the most powerful political force in the world today. I also can’t help noticing that well-meaning people on the left have grown increasingly afraid to invoke that kind of collective sentiment. And when they leave this nationalist or patriotic space vacant, the worst kinds of people come to fill it. In the past I’ve described nationalism as a half-domesticated animal, which still can be stoked and provoked and still can run wild. It still can become incredibly destructive. But a half-domesticated animal also can be useful. Historically, patriotism and nationalism also have expanded the circle of human sympathy (including in terms of religious or secular or ethnic or gender identity, and so on). Nationalism can enable us to connect with people who live far away, and with whom we have little else in common.

Many countries, even with deep nationalist traditions, have figured out ways to be inclusive. There has always been an American tradition in which to be a citizen should have less to do with blood or religious creed than with the democratic ideals to which you subscribe. So with this phrase “inclusive nationalism” I want to suggest a higher form of solidarity with one’s fellow citizens — who can be anyone, who might have come from anywhere. One type of prevailing populist nationalism right now of course focuses on ethnic nationalism, white nationalism, in order to create a narrow idea of “true” American nationality. But if you look at polls, relatively few people actually believe in this. So in the long run I feel less concern about our ability to win that particular battle. But I do see a broader danger in the idea that being a “true” American means accepting some sort of demagogue and / or some form of aggressive militarism. We’ve seen those more chameleon-like tendencies (which can take on a variety of forms) exploited throughout our history. So that long-term trend worries me much more.

Distinctions between shorter-term and longer-term dynamics also play out as you distinguish between Trump supporters driven by economic suffering, and Trump supporters driven by economic anxiety (with such supporters perhaps comfortably above the poverty line for now, but lacking college degrees, stuck in non-professional jobs, facing ominous prospects amid forces of globalization and automation, measuring their security in relation to projected future threats as much as to present circumstances). Future-oriented anxieties also arise in largely homogenous communities seeing increased diversity elsewhere, and sensing that their own internal composition soon will shift in accordance with these trends. So how does political theory, and how do everyday political conversations (in terms of research questions they pursue, social critiques they offer, aspirational visions towards which they wish to guide us) need to change in order to constructively engage this future-oriented perspective of supposedly “backwards” populists? What would be basic elements of a future towards which liberals, democrats, liberal-democrats, populists of various sorts might agree to move together?

We do need to get over this smugness of thinking that the future is ours and ours alone. When I was growing up in Germany, we would talk about the far right as Ewiggestrige, “those forever stuck in the past.” But now we can see that it was naive to think neo-Nazis would eventually be swept away by an inevitable liberal-democratic future. The far-right Alternative für Deutschland (or AFD) recently has emerged as the second-largest political party in Germany. The political future in which our basic ideals prevail still needs to be won every single time.

And predictions of a socially progressive demographic majority inevitably emerging in the U.S. are also very naive. First, this assumes a kind of one-drop rule, in which somebody with one Latino grandparent, who might actually identify as white, still gets categorized as (and votes like) somebody who identifies as a person of color. Second, this patronizingly assumes that minority groups (many of which have some quite conservative cultural traditions) never would vote conservative, so that the progressive coalition can simply take them for granted. And of course we also reductively categorize all “Asian Americans” together. We don’t differentiate between Latino voters whose families come from Cuba and those who come from Mexico. So we should be very careful with these future predictions, and we should ask ourselves much more self-critically: what persuasive vision can we present to our fellow citizens about the future?

Populists often harken back to the past, but they also appeal quite personally to how they can make your life better in the future. Too often, the people standing up to populists forget this charismatic power of populist visions. But we need to recognize this power, if only to push ourselves to develop our own compelling visions that citizens can support and feel supported by. We can’t just assume that criticizing somebody else’s vision is a sufficient political project.

Again in terms of these complex multigenerational dynamics, when might an apparently undemocratic liberalism in our present reflect the preserved moral imperative of preceding generations? Could we ever call it “democratic” for 250 years of precedent, and / or for the well-being of subsequent generations, to take preeminence over citizens’ impulsive preferences in the present? Or where might the concept of presentism likewise fit alongside democracy and liberalism?

Well first we probably need to distinguish between framing the space of politics, and delimiting particular public-policy choices. We can’t define “the will of the people” in the abstract, without a set of institutions that facilitate the manner in which the people come to their decisions. And here it doesn’t particularly trouble me that the constitution’s founders framed 250 years ago how we conduct our present politics. That historical fact doesn’t need to constrain our contemporary world. But it can help us come to collective decisions.

I do see a problem though when people who lived 250 years ago decide matters of substantive public policy for us. I actually think left-leaning liberals have sometimes too willingly let the Supreme Court overreach into areas like gay marriage, which we would have been much better off deciding through state legislatures. I think we would have won that battle in, say, 46 of 50 states. So we can and often should rely on constitutions and inherited institutions like the Supreme Court, both of which help to ensure that popularly elected executives (and other government officials) do not overstep the bounds of their authority. But the scope of decisions on which these inherited institutions can constrain us should be narrow.

Here again, while you acknowledge the no-doubt unjust (white-supremacist, patriarchal) hierarchies of power that our liberal democracy has reinforced throughout its history, you also suggest that liberal democracy’s left-leaning critics often fail to acknowledge how much worse off we all might be (social minorities certainly included) if no liberal state stood between the individual citizen and the majority will. So in terms of how you might assess problematic tendencies percolating on today’s intellectual left, could you describe ways in which a self-described anti-Trump, anti-authoritarian critique itself might betray tendencies towards undemocratic liberalism (“I don’t care what the racist majority thinks”), or betray tendencies towards democratic illiberalism (“Basically everyone in my community agrees with me, and any outliers should be ostracized for their deviations”)? Or for a straightforward question: you say much more needs to be done to think through what a truly liberal, truly democratic, liberal-democratic vision might look like. Could you start to offer such a vision here?

Sure, though I often do find it strange to engage in fantasies of the kinds of democracy one wants to build — right now for example, a couple weeks before the midterm elections, when one’s own political group currently possesses so little power. Still I do have some substantive frustrations and fears about some of those changes you describe happening on the left. I do believe for example in freedom of speech, and consider it problematic to overthrow that principle in the name of supposed progressive ideals. Of course you can sit in your little progressive bubble, and imagine how much better off the whole world would be if only you could decide for us all what can and cannot be said. But you shouldn’t forget the everyday reality of the people who can truly quash public speech (say the presidents of large state universities across the South and Midwest, who get appointed by and remain accountable to Republican governors and legislatures).

In the same way, I recommend that before you indulge in court-packing fantasies, it helps to regain power in at least one of our three branches of government, and to make sure you can continue to hold that power for a long time to come — because of course the other side can use these same partisan tactics against you. So I do consider some of those proposals cases of bad judgment, compounded by fantasy.

Well The People Vs. Democracy also cites the historical overlap between a post-World War-II international expansion of invigorated liberal-democratic politics, and a stunning span of peaceful economic growth — perhaps persuading populations to support this political system more for the immediate gains it provides than for any fundamental commitment they might feel towards the timeless values it puts forward. So today, when those economic gains, when that sense of comparative security no longer can be taken for granted, do we face questions such as: to what extent do we or did we ever (whoever “we” might be here) really want “democracy”? To what extent did we just mean: “We want the prevailing order, so long as it doesn’t get in our way too much, and our income keeps rising”? Or what happens when the popular majority doesn’t in fact want liberal democracy, and maybe never did?

Here I wouldn’t say it so starkly as: “People either wanted democracy for all the right reasons, or they didn’t want democracy at all.” In fact I hope for this book to challenge precisely that kind of binary thinking, in part by examining the nature of public support for liberal democracy throughout the postwar era. People embrace a political system for various (partially overlapping) reasons. For example, within the postwar Western European context, people might have embraced liberal democracy in response to experiences with fascism and / or communism, or due to increased appreciation for individual liberty and collective self-determination. But we also shouldn’t forget that many Western Europeans initially skeptical of liberal democracy were won over only once this system started delivering for them. Eventually they could see that liberal democracy in fact offered them a very appealing bargain. They got to embrace high-minded ideals like individual liberty, but at the same time they benefited from tremendous growth in living standards.

From that historical model, I draw the lesson that we need both a more abstract idealistic and a more practical economic basis for legitimizing our liberal-democratic system over the long term. I suggest that we need much more substantial and ongoing civics education, including at the university level, including in publications like the Los Angeles Review of Books. We as teachers, writers, and thinkers need to clarify for people not just the inevitable flaws in our current political system, but also what we find distinctly valuable and worth preserving in our political system. But we also do need to put in place significant economic reforms, significant policy changes designed to ensure that people can have a good life, and can feel optimistic about their own futures.

Given any number of topics we’ve discussed, I do sense one fundamental rhetorical tension circulating throughout The People Vs. Democracy, a tension in which you seek to convince us that these extraordinary times demand extraordinary responses, but in which your desired outcome would involve us largely preserving our liberal-democratic social order — rather than blowing it up. Or we here could consider contemporary electorates telling pollsters that they want both a politics of the center, and a politics of change, and ask: what does it mean to fight for the preservation of order? Or how most constructively to frame this less as a fight to preserve liberal democracy than as an effort finally to fulfill the long-held promise of liberal democracy?

The goals of liberal democracy (to create a social order in which individuals can live free from all forms of discrimination, and can prosper enough to pursue personally meaningful lives) are plenty radical. They already pose incredibly difficult challenges. Some countries today (including the U.S., but especially Canada and certain countries in Western and Northern Europe) come closer to realizing these ideals than any previous society. But that still leaves us far from fully realizing liberal-democratic ideals. So liberal democracy’s defenders do need to avoid the trap of identifying too closely with the political status-quo. We are not some “establishment” who considers everything to be okay. We are the partisans of two deeply inspiring ideals, and we seek to ensure that reality accords ever more closely with these aspirations.

If we can refashion our approach to liberal-democratic commitments in this way, then I think we still can prevent ourselves from throwing out the baby with the bathwater. We can reject an approach which says that the path to human improvement could only come through political extremes — extremes which, either on the right or left, usually bring tyranny and ultimately poverty.

So yes, we do need to fight, but instead of pursuing such extremes, we should focus on contesting concentrations of power. We should contest the role of money in our politics. We need to contest economic policies clearly favoring those who already have over those who have not. We need to struggle to realize, for the first time in human history, a truly equal multiethnic society.