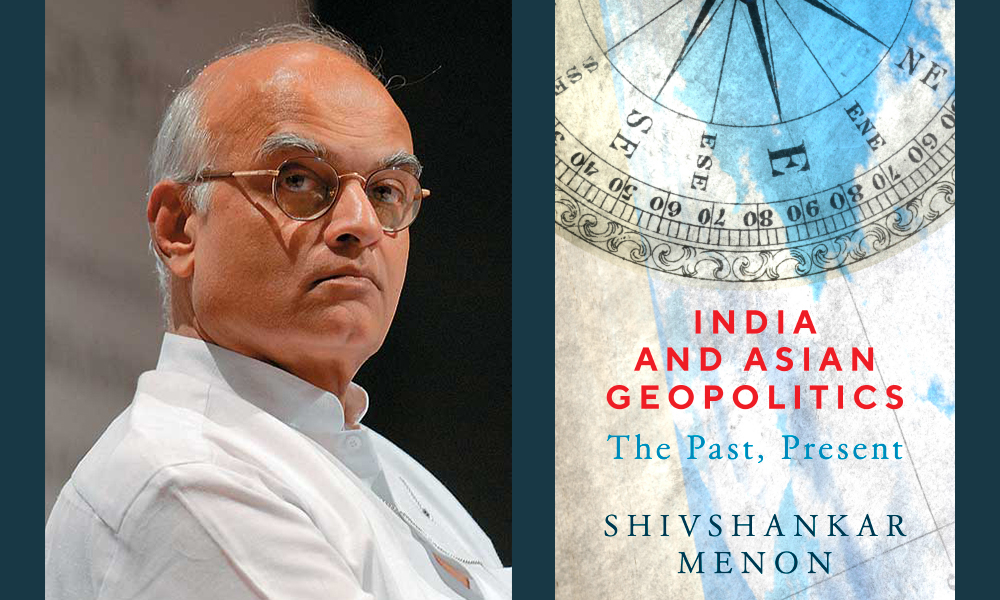

How might both India and Pakistan come to better recognize their own self-interest in working together? How might India, China, the US, and fellow nations come to reprioritize freedom of navigation across the entire Indo-Pacific region? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Shivshankar Menon. This present conversation focuses on Menon’s book India and Asian Geopolitics: The Past, Present. Menon served as national security advisor to the Indian Prime Minister from 2010 to 2014. He currently serves as chairman of the advisory board for the Institute of Chinese Studies in New Delhi, as a Distinguished Fellow at the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, and as a Visiting Professor at Ashoka University. He is also the author of Choices: Inside the Making of Indian Foreign Policy. In 2010, Foreign Policy magazine chose him as one of the world’s “Top 100 Global Thinkers.”

¤

ANDY FITCH: To counter any monolithic conception of “Asia,” could you first sketch, perhaps from an Indian perspective, a framework for considering this region, historically and today, as a pluralistic multiverse?

SHIVSHANKAR MENON: If you look historically at Asia as a whole, it always has had two or three universes sufficient unto themselves, in terms of politics and security. But these universes also have been consistently trading, communicating, and exchanging ideas (religions, science, technology). People always have traveled between them. One universe, in east Asia, was centered basically on China, as the source for a lot of its culture. Another universe, in the Indian Ocean world, has had India as its center, as the place where everything spreads out from (such as with Buddhism), or where everything intersects (such as with Islam traveling through India to southeast Asia). Then you also have west Asia, where Persia (today Iran) has been the dominant power for long periods, with other powers sometimes as well — such as with Egypt intervening in the Levant and the Middle East when it suited her, and later Turkey under the Ottomans, and now Israel.

So these three universes, as components of the Asian multiverse, always have interacted in positive ways, but not typically as part of each other’s political or security calculus. Only with the Mongols do you start seeing unification across this whole steppe, from the Pacific all the way through to the Hungarian plains, bringing the first big wave of globalization.

A second big wave of globalization crested just before World War One. Keynes captures this perfectly when he describes an Englishman sipping from bed his breakfast tea which literally comes from around the world. Until about 1750, Asia had accounted for roughly two-thirds of world GDP. But then due to the Industrial Revolution and the Great Divergence in the 18th and 19th centuries, Asia became part of a European-based imperial structure. Of course, after World War One, this wave of globalization suffered a huge setback.

The next big change came after World War Two, when many countries started taking their future into their own hands, whether through the formation of the republics of India in 1947 and of China in 1949, or through the decolonization spreading across southeast Asia and the Middle East and Africa. Finally, by the 20th century’s second half, we arrived at an international structure with state sovereignty formally established across much of the world, with all states officially equal (each receiving one United Nations vote, for example), but obviously not equal in practical economic or security terms. Within this new global structure, some facts of the old geographical multiverse still applied. But on top of those, you had an overlay of political, economic, and technological forces both connecting and dividing us in new ways.

Today we can in fact speak of Asia as one expansive area, but still with many localized pressures in east Asia, in the Indian Ocean world, in west Asia. Today you have this interesting mix of ways to look at Asia, and to define Asia. I remember, in the US in the 1960s, when I’d mention Asia, people thought that meant Vietnam. Thankfully, the definition has expanded. My book looks at how these conceptions have changed, how Asian geopolitics have changed, and how India fits into all of that.

In terms of India’s distinct geopolitical pressures, could we start with the planet’s only subcontinent prompting dual inclinations towards solitary existence, and towards engaging a broader world beyond this self-contained geography? And could you make the case for a population-rich but resource-poor Indian society thriving most when promoting subcontinental cooperation, and/or reaching outwards through maritime trade?

Yes, just the word “subcontinent” suggests India’s unique situation as part of the world’s central landmass, while also being separate at the same time. We Indians do have a tendency to think of ourselves as somehow different and exceptional, and to concentrate on the subcontinent’s own affairs. Throughout history, the subcontinent’s polities have done best when most connected to each other, and when most engaged with the outside world. Those parts of the subcontinent connected to the sea have traded with the rest of the world for three thousand years, facing outwards, for example, from the Malabar and Coromandel coasts — transit points which connected southeast Asia and China to west Asia, and to the big civilizations further west (with Pliny complaining about India draining all the gold from 1st-century Rome). That reaching outwards from India’s coastal regions always has been an important part of the subcontinent’s push and pull.

America might have a historical tension between isolationism and US visions of itself as a global leader. India, by contrast, never claimed to be the city on the hill and so on. Its condition at the birth of the republic in 1947 was pretty abject. After two hundred years of colonialism, one of the world’s richest and most advanced societies had been reduced to one of the poorest and most backward. Life expectancy was about 26 years in 1947. The economy had only grown 0.005 percent over the 20th century’s first 47 years. Hunger, poverty, and illiteracy were endemic.

India first needed to concentrate on transforming itself, and to see whether the world could provide an enabling environment for that. In the mid-20th century, we lacked the raw materials and the technology and the capital to develop entirely on our own. We still depend on the world for energy. We depend on the world for nonferrous metals. 80 percent of our imports simply allow us to obtain necessary resources and supplies, such as fertilizer.

Because we’ve needed the world, we also have needed to engage the world. We tried a form of autarky for a while, but it didn’t work well, and so we’ve opened back up to the world. And since really opening up, starting in 1991, the Indian economy’s high-growth years have pulled an unprecedented number of people out of poverty. From 2001 to 2011, we pulled something like 140 million Indian people above the poverty line.

So for me, this book’s basic lesson is that India must engage with the world, and primarily with our immediate neighboring nations. And the book’s subtext focuses on how the Asian geopolitical environment itself has become much more complex in the past 30 years or so. It’s an incredibly interesting time, so let’s see where we go.

India and Asian Geopolitics makes the case that India long has faced a bind of needing cooperative transnational engagement, but not finding any other nation’s interests entirely overlapping its own. How has India, since emerging from colonial rule, sought to manage such tensions through, say, Jawaharlal Nehru’s notion of nonalignment? And what continuities have you seen as 21st-century India continues to explore what “strategic autonomy” might look like at the regional and global level?

I consider strategic autonomy basically as nonalignment for the 21st century. They stem from the same impulse of not getting entangled in alliances which would make your decisions for you. They flow again from our unique geopolitical situation. Certain Indians have used these conditions to argue for Indian exceptionalism. But my book suggests that none of India’s distinct conditions or distinct challenges means that we can just go it alone, and not worry about the rest of the world. We are an important part of that world. That world, in turn, has a huge impact on our prosperity and security. We’ve actually become increasingly dependent on the world.

We also have been fortunate in finding good partners. Over the past 30 years, for instance, we’ve seen increasing congruence between Indian and US interests. The US has played a critical role in India’s longer-term transformation since the Green Revolution of the late-60s and early-70s. The application of US technology in improved seeds and fertilizers allowed us to feed our population ourselves. Since then, India and the US have worked much more closely, and have come to see the world in quite similar terms. That doesn’t mean a formal security alliance between these two very different countries. But we work together.

Similarly, we’ve worked with the Russians. We’ve worked with Iran on many topics, all while preserving nonalignment or strategic autonomy. From my perspective, this multidirectional policy approach of working with a variety of partners on shared interests has served India well so far. It hasn’t always been the easy or popular choice. It has gotten harder and harder, as the world becomes more polarized again. But as a natural outgrowth of our location, our history, and our recent development: so far so good.

In your book’s account, modern India’s most enduring geopolitical tensions stem from its birth, with Pakistan’s simultaneous creation. The Indian nation emerges as the subcontinent’s center of gravity — but with this central hub of the Asian multiverse suddenly much more constricted to its west. How have Partition’s legacies come to shape the subcontinent’s fraught status as perhaps the world’s most integrated region in ethnic and cultural and linguistic terms, while also one of the world’s least integrated regions in trade and investment terms?

Two things happened immediately with Partition. From a regional perspective, the creation of Pakistan physically cut off India from central Asia and west Asia. Simultaneously, the British Royal Navy withdrew from the Indian Ocean — making India’s seafaring routes to west Asia much less secure. And then from a national perspective, while India gained independence from Britain, Pakistan gained its independence from India. The Pakistani state was built around this founding ideology. From the start there were adversarial and hostile relations, with a war in year one. So India always has faced this difficult and quite large neighbor (Pakistan has the world’s fifth-largest population). That changes Indian geopolitics fundamentally.

Similarly, because of the manner in which the British left, the subcontinent’s political unity gets broken into a whole series of emerging states, whether Ceylon (which had been administered separately by the British, under the colonial office), or Burma (which had been administered from India by the British until 1936). Nepal had nominal independence and an ambiguous relationship with the British. Each of these arrangements then had to be redefined and managed, which took a lot of effort in the early years. Old nations with new states had to build their own modern national identities — and all alongside India, as the subcontinent’s overwhelming presence.

Tremendous affinities of language, culture, religion, and ethnicity exist. Every nation in south Asia has significant cross-border ethnicities. You can’t really call any of these “natural” borders. I mean, Mizos on our side are Chin on the Burmese side. So when the recent coup happened in Burma, India’s national government might have said: “Close the border.” But the local government and people said: “How could we keep out our cousins? We marry into these communities. We’re the same tribes.”

But for formal metrics of integration, trade for instance, only six percent of the subcontinent’s cross-border commerce stays within south Asia. Most of our trade flows outside. We also barely invest in each other. Huge numbers of workers might cross these borders for their livelihood, producing very large figures for remittances, with billions of dollars sent from Bangladesh to India, and from India to Bangladesh, and to Nepal and back. People’s lives have become so much more integrated than is often recognized. But as formal Westphalian states, we still haven’t integrated very much at all.

Here could we also follow up on what you describe as the Pakistani state’s “institutional hostility” towards India, fostering the militarization, Islamicization, and eventual Talibanization of Pakistan’s own political culture? When has India best succeeded in establishing constructive dialogue with Pakistan — and what space did such foreign-policy gains create for India to pursue “much more important goals” back home or throughout the region?

Frankly, we’ve never quite solved the conundrum of our relationship with Pakistan. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan’s founder, used to say that Pakistan should be to India as Canada is to the US. But over time, through wars and various kinds of bitterness, this relationship has grown even more difficult. At least in the 1950s and 60s, generations of leaders on both sides had experience living together, attending the same schools, knowing each other personally, and recognizing the need for diplomatic give and take. That has faded as each country has evolved in different ways over the past 70 years.

But I remain relatively optimistic about south Asia as a whole. India-Bangladesh relations, and India-Sri Lanka relations, provide useful comparisons. Both relationships have greatly improved. We’ve started to integrate by allowing more travel, trade, trade in energy (for instance, electricity across borders). Ultimately, India and Pakistan likewise need to see our own self-interest in working together — with our prosperity and our security of course interlinked. Neither of us can thrive in peace if the other does not.

So yes: this book documents an institutional hostility towards India, fueled by the institutional self-interests of the Pakistan Army and Pakistan’s very powerful intelligence organization, the ISI. The jihadi tanzeems also promote a very narrow future for Pakistan. That vision has stymied Pakistan, in contrast to a largely secular India.

But I don’t see the rest of Pakistani society being institutionally hostile to India on the whole. In fact, the Pakistani state itself remains underdeveloped in many ways, and still a work in progress. Whether we’re talking about Pakistan’s civil society, or the ordinary Pakistani on the street, or Pakistan’s business sector, each actually has gained from better relations with India. And even some civilian politicians have become more willing to make this effort. So my own sense is that we clearly can see some give here. I therefore think that we as Indians need a much more nuanced approach towards Pakistan, allowing trade, travel, and other innocent forms of exchanges — and basically isolating those more dangerous institutions.

For one additional westward-facing question, could you outline, for US readers, India’s long-standing constructive relations with Iran, and why India has good reason “to stay clear of attempts to isolate and contain Iran”?

Well frankly, what are India’s interests in west Asia? This region provides much of our energy. 63 percent of the oil we import comes from the Persian Gulf. And we saw in 1973 and ‘79 the domestic chaos created if oil supplies get cut off, or if prices rise through the roof.

We also have a fundamental interest in peace and stability across west Asia, and the Gulf in particular. We have about 7 million Indians living and working in the Gulf. We received in 2019 something like $73 billion of remittances from these workers. We couldn’t just immediately evacuate 7 million people if something went wrong. We also don’t want these states further radicalized. We don’t want the Indians working in these nations to be influenced by extremist forces, then fed back into our society.

We’ve found Iran a useful partner on many of these concerns. We’ve also found Iran a useful partner on overcoming the geography created by Partition. Our access to Afghanistan actually comes through Iran, through the Delaram-Zaranj Highway by land, and through the port of Chabahar on the Gulf.

The security of the sea lanes bringing our energy to us has become extremely important. Through transforming into a net energy-exporter, the US has begun to eliminate its reliance on oil from this region. Traditionally, many nations in Asia and the world have benefitted from the public good, the security, provided by the US Fifth Fleet, based in Bahrain. But today we hear the US discussing restarting its First Fleet, further east — presumably by redirecting personnel and materiel from other fleets. Again, let’s see. The countries today with the greatest interest in Gulf maritime security, and in keeping those sea lanes safe, are countries who depend on the Gulf’s oil: India, China, Japan, and Korea. This whole map, this whole geopolitical picture, will keep changing in fundamental ways. In the last month, I believe the US exported more oil to India than to any other partner, which gives you an idea of how quickly this dynamic keeps changing.

Now to begin turning east, could we take up the model of a dynamic reordering of east Asian and southeast Asian economies by the 1980s? Could we bring in how the demise of Cold War binaries, by this decade’s end, starts to liberate Indian diplomacy? How, under Narasimha Rao and Manmohan Singh for example, do pragmatic economic liberalization in domestic policy, and strategic autonomy in foreign policy, converge in mutually reinforcing ways that will shape India’s next quarter century?

To my mind, the Cold War’s end liberated India. On one hand, the Cold War binary had enabled nonalignment. India figured out how to work between these blocs, and pursue its own self-interest. But then by the time this Cold War binary ended, we already had entered a globalizing era. Throughout the 1970s and 80s, Japan had done significant work building global supply chains, connecting east Asia and southeast Asia, linking this whole region economically to the rest of the world. Japan also showed export-led emerging markets that it was possible to transform into a modern country, with a modern economy. Taiwan, Hong Kong, Korea, and Singapore followed in what today we call the “flying geese” pattern. Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines took significant steps to integrate themselves into this regional economy. India, like China, came to these developments a little later. The Cold War’s immediate end coincided with a domestic economic crisis in 1990-91. But between Prime Minister Rao and Dr. Singh (Rao’s finance minister, and later prime minister for two terms), India’s leadership saw the opportunity not just to liberalize its domestic economy, but to unshackle itself internationally.

That liberated us to work with new partners. Prime Ministers Rao and Singh both recognized early on that the world’s economic dynamism now came from east of India. In April 1992, Rao delivered a speech in Japan, about India’s “Look East” policy, which started with Japan, but soon also included China and Taiwan. Within a year and a half, we had opened a diplomatic office in Taiwan. We managed to work with both governments simultaneously. We also worked with ASEAN, getting dialogue-partner status, while concentrating on building first an economic, and then later a security and defense and political relationship with southeast and east Asian countries. Rao was the first Indian prime minister, for example, to visit South Korea.

The Cold War’s end also liberated us to our west. We had long recognized Israel, with an Israeli consulate in Mumbai. But we’d never upgraded relations to the ambassadorial level, until 1992. And more broadly, once we opened up the economy, our entire perspective changed. We did manage to quickly clear up some debris from the Soviet Union’s collapse, issues of debt and so on. That was quite an achievement. Yet the most consequential transformation happened in India-US relations — carried out not just by Congress governments, but also by Rao’s successor, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the first BJP prime minister.

You describe the September 11th attacks then bringing forth unprecedented India-US security/intelligence cooperation, yet with the US still failing to fully grasp Pakistan’s central role fostering international terrorism. You describe US preoccupations enabling the broader Asia Pacific to focus on dynamic economic growth — while leaving an increasingly assertive China free to start staking out expansive territorial claims, to ramp up domestic authoritarianism, and to postpone pledged reforms. From an Indian perspective, what would you most wish US foreign policy to have seen more clearly in September 11th’s aftermath?

Well with the Cold War’s end, I would have expected the US to reexamine its relationship with China much more fundamentally. When the US opened to China, and brought China into the family of nations in 1971-72, if you look at the transcripts, Henry Kissinger actually tells Richard Nixon: “in 20 years your successor, if he’s as wise as you, will wind up leaning towards the Russians against the Chinese.” But I think the US went on autopilot, even after Tiananmen, and after the Soviet Union’s collapse. I don’t think the US quite realized that its China engagement would lead directly to creating a competing power.

I still find that puzzling, because the US tends to reevaluate policy quickly, and to change tack when necessary. She’s the only country, actually, who does this. She has remade herself four times in my lifetime. She has an admirable knack for quickly analyzing and learning from experience. Within three years of George W. Bush entering Iraq, you hear analysis after analysis of what went wrong, and what in US policy needs to change. But you don’t see that with America’s China policy. China remains the exception. And that surprised me, especially after 9/11, when from an Indian perspective, two points stood out clearly.

India saw this moment’s terrorism problem as primarily coming from Pakistan — but the US, not so much. Then once the Taliban had been driven out of power in Afghanistan, we all knew where they’d gone. We knew where they found shelter. We knew who kept them going. Basically, they had three shuras operating in Pakistan, and they got sanctuary there. Similarly, after Tora Bora, it became quite clear that Osama bin Laden only could have gone to Pakistan, where he was kept quite safe, as the American public would see later. But the focus on Iraq already had taken over.

All of this distracted much of the world from major developments in the Asia Pacific. By the time the US restored its focus on the Asia Pacific, during President Obama’s readjustment policy, the Asia Pacific itself had changed. China had quickly transformed into the biggest trading partner for many east and southeast Asian countries. Supply chains, value chains, all ran through China. China didn’t yet dominate them all, but they all passed through China now in one way or another. Regional relationships had grown much more intertwined, and much more complex.

But today I can only offer 20/20 hindsight. At that time, public officials faced their own electoral cycles and political calculus and daily fires to put out. I know how hard that can be. I consider it unfair to second guess them, looking back. In any case, what’s done is done. We might as well accept where we’ve landed, and try to make the best of this situation.

So today then, to what extent do you see Chinese actions in the South and East China Seas fundamentally undermining US-based balance in the region? To what extent do you see the US still failing to offer an adequate counterstrategy? And why and how should India respond by prioritizing positive-sum freedom of navigation for all, throughout the Indo Pacific?

For India, almost 50 percent of our GDP now comes through global trade, with 90 percent of this trade shipped by sea, making open sea lanes critical to our prosperity and future growth. These sea lanes must stay accessible and safe for all — not exclusively for any limited group of countries. The South China Sea alone, for instance, carries about 38 percent of India’s foreign trade. So for me, freedom of navigation across the entire Indo-Pacific region, and for all regions, stands out as essential.

Of course the globalization decades have made freedom of navigation critical to China as well. We tend to underestimate this, but close to 40 percent of China’s own GDP comes through the external sector. She is very powerful economically, but also very dependent. And she doesn’t have much historical experience with this arrangement. She has depended on the outside world for energy since 1994, when she stopped being self-sufficient in oil. She depends on the world’s technology. She depends on external markets, for access to raw materials. She needs to keep exporting, as a central part of her economy. She wants to shift to domestic consumption, but hasn’t made that shift yet. So for China as well, freedom of navigation has only grown in importance.

But now the South China Sea also has become a significant arena for China’s increasingly tense strategic competition with the US. China has the world’s greatest armada (the US Navy), 12 nautical miles off her coast, in her face. She sees the first island chain as a form of containment, as a great wall in reverse, preventing her from shaping her maritime environment, so crucial to her prosperity and security. So she feels justified claiming the entire South China Sea, and trying to enforce these claims by changing facts on the ground: building islands, militarizing them, pushing forward, declaring this space a core national interest, which makes any competing claims almost non-negotiable, because now we have a foundational sovereignty concern — not just some friction which you can accommodate and settle through some give and take.

The geopolitics around this have gotten much, much more complicated. China, the US, India, and other nations can’t help rubbing up against each other. No mutually accepted set of rules applies. The Chinese didn’t accept the tribunal’s decision when the Philippines took them to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 2016. So China doesn’t seem to accept everybody else’s interpretation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. The US abides by this convention, but has never ratified it. So we face this peculiar and unprecedented situation today. We don’t have the proper institutions. We no longer have the established norms of living peaceably and maintaining the collective security of these sea lanes. We really need to work together on this. Maybe we can start by isolating parts of the problem that serve everybody’s interests. Maybe we first should focus on navigation of the high seas, for example, and then try to build momentum towards addressing more delicate issues, such as military passage.

In your book’s account, contemporary Chinese maritime ambition stems from China already having consolidated power across central Asia: with this region’s nations quietly turning towards China following Russia’s unchecked interventions in Georgia, and with Putin himself feeling less threatened by China than by an encroaching West. What do US audiences need to see more clearly about how the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and various Belt and Road Initiative projects, have woven a subtle net of trade, finance, infrastructure, connectivity, and security webs across this vast continental terrain?

China’s central Asian frontiers had always been disputed and fluid. Throughout her history, her primary security concerns have almost always come from the northern or western “barbarians.” But for the first time, she now feels comfortable on these flanks. In fact, she’s consolidating the Eurasian landmass through the Belt and Road Initiative: through railways, trade, fiber-optic cables, pipelines, and the like. She’s creating a continental system in which all roads lead to Beijing.

So China, traditionally thinking of herself as a continental power, now sees opportunity to significantly expand her maritime presence. And it actually takes a whole different mindset to think like a maritime power. Again, China senses her increased strengths, but also her increased dependence. She finds herself in a very unfamiliar position. From my perspective, some of the primary tensions we face today probably come from China seeking to find her footing in international circumstances unprecedented for all sides, and certainly for the Chinese.

You also describe China itself potentially facing a closing window for expansive policy — before a slowing economy, an aging population, and rising neighbors catch up with it. What could we see China attempting before this window of opportunity closes? How might China continue shaping the region even after this window for robust assertion closes? And how should India be proactively positioning itself for each of those scenarios?

Of course this is my book’s most speculative part. Nobody can predict China’s trajectory. We have authors writing books on China’s coming collapse, as well as books on China soon ruling the world. The coming-collapse people have to publish articles every year explaining why it hasn’t happened yet [Laughter]. The when-China-rules-the-world people will have to explain the slight delay. But it seems to me that when you look at long-term drivers of policy, not all of them stack up in China’s favor. The Chinese themselves describe this present moment as a “strategic opportunity” for China. And over the last year, they’ve started to say that this present regional situation has gotten much more complex.

One big variable is US pushback, and what China sees as US opposition to China’s return to its rightful place — at the head of the international order. The Chinese have taught themselves this version of history over the past two decades, stressing a century of humiliation, before China resumes its status as the world’s most advanced, prosperous, and powerful society. The Chinese do in fact seek primacy, it seems to me, after having taught themselves this history.

They see US pushback as making this much more complicated. Their own demography also works against them right now. Thanks to the one-child policy, they have a rapidly aging population. Their economy seems to be reverting to its historical mean in terms of expansion and new job opportunities and so on. China also finds itself, as always, in a crowded neighborhood, but now with other relatively powerful countries rising. I mean, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, India, and Indonesia all have their own regional clout. China faces a very different situation from, say, previous global superpowers like Great Britain or the US — in geopolitical terms both basically islands, secure in their ability to withdraw and remain offshore balancers to much of the world.

By contrast, the Chinese today might see the need to hurry to achieve their goals. To start with, this might mean completing China’s reunification. They’ve persistently emphasized this goal. Taiwan holds several strong attractions for a Chinese leader. We’ve already discussed some of the maritime and geopolitical dimensions. Any Chinese leader who brings Taiwan back into the fold would place himself on the same level as Mao Zedong (under whom China stood up) and Deng Xiaoping (under whom China prospered). Taiwan also of course plays a leading role in key tech industries.

China’s remaking of its domestic society today also furthers this traditional Chinese ideal of a homogenous, centralized state. China’s political leadership always has sought to build centralizing structures. Today these pressures surface in China’s treatment of minority populations, in what’s happening within Xinjiang, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia (where local languages no longer are encouraged or taught). Everybody now learns Mandarin (or really Putonghua, “the common speech,” as they call it).

So you can see various efforts today to build a China of the China dream. But when you look at what this China dream involves, it actually recalls a late-19th-century European dream of a nationalist power, prosperous and projecting a very strong military. Lee Kuan Yew, when asked once where China was heading, responded: “If I were Chinese, I would aim for primacy, and good luck to them. But if they ever achieve primacy, good luck to us” [Laughter]. That’s the unsettled stage we’ve reached today. We can only make an educated guess at China’s trajectory. And the future never offers a straight-line extrapolation to connect the dots. It never has, and never will.

So as global power shifts back to Asia, we also, in your account, should expect to see such power continuing to shift within Asia, rather than settling into some sturdy new equilibrium. Given these dual trends, what could a multipolar, inclusive, and also flexible economic and political and security order look like in Asia — an order perhaps driven less by dominant powers, than by issue-based coalitions of the willing?

Right, my own sense here comes from witnessing these very rapid shifts in the balance of power (whether economic power, military power, political power, or even soft power, say through K-pop) over the past 30 years. That accelerating pace has many people struggling to get their heads around all of this change. But the more we try to impose stability on this system that’s bubbling over and changing each day, the less we’ll actually be able to navigate these waves. So instead, I think we need to focus much more on managing change.

And how do we manage change? We need to prepare for crises, which we know will happen. We need effective crisis-management mechanisms. We need everybody talking to each other, so that each nation has some sense of what drives the others, and why they act the way they do. But most importantly, for critical concerns, we need to build issue-based coalitions of the willing and able. Maritime security again comes to mind, as critical to all of us. Cybersecurity comes to mind as a new domain of contention. Ongoing international terrorism comes to mind. We face a whole host of issues where shifting sets of partners will need to cooperate, based on their mutual interests and their respective capabilities.

How did we deal with piracy off the Horn of Africa in 2008? A coalition of the willing came together, all reliant on the free flow of oil and trade through those waters. This involved NATO. It involved India. It involved China. It involved Japan as well, who sent naval units. It extended all the way to Australia. That provides a useful model for various fluid situations, in which you can’t expect some rigid institutional structure to deal with a rapidly developing problem. You have to work flexibly with each other. That doesn’t come easy. It requires painstaking diplomacy. But it’s worth all of that effort, given the alternatives.

And amid this need for ambitious reimaginings of regional and international order, what most pressing dangers do you see (within China, India, the US, and elsewhere) for increasingly chauvinistic and nationalist public discourse (fueled by a politics of emotion, prejudice, resentment) to drag us down from more high-minded pursuits?

This is what really worries me Andy, this authoritarian tone in domestic politics across the world, coming partly in response to the globalization decades — because globalization threatened local identities, but also because governments’ ability to deliver has declined across the board in many nations. The less these governments can deliver, the more they rely on that last refuge of the politician: nationalism. We’ve seen numerous governments get more authoritarian. And when they then have to base their questionable legitimacy on hypernationalism, they lose their ability to compromise, to give and take, to negotiate. Diplomacy by definition means adjusting and compromising: determining your most critical interests, and protecting these interests, while also allowing others to do the same. Those capabilities have diminished considerably for many countries. We’ve seen that in the multilateral system’s failure to respond to this COVID pandemic, for instance. Where was the world? Where was diplomacy? Where was our multilateral system over the last year?

As relations between global and regional powers grow more tense, more uncertain, security dilemmas of various kinds have arisen across the world: whether between India and China, or Japan and China, or the US and China. In each case, each side perceives the other’s actions as aggressive. Both sides see themselves as taking purely defensive steps. But then you enter a cycle of reaction, counterreaction, and escalation. If everyone already has compromised their ability to negotiate, then frankly we’ve reached a quite difficult position.

Returning then to the prospect of China’s window of opportunity closing, why should India not rest on any self-assured projections of its young dynamic population soon coming into their own? How could, say, a form of tech-driven economic growth that does not include significant job gains reshape India’s potential demographic dividend into a demographic nightmare? And what steps can India take now to help prevent such a scenario?

Well I do see a risk that we miss the bus on becoming a prosperous, secure society where any Indian can achieve their potential. That risk has grown over the last few years. But I still consider it only a risk. And I have three strong reasons for optimism. First, we’ve shown a significant capacity to learn from experience, to change, and to improve. Indian policymakers haven’t simply done the same thing over and over again, while sometimes expecting different results. No, we’ve built on important lessons from our post-independence experience. We’ve learned from failure. We’ve actually moved on. Look at our longer-term economic policy. Look at our longer-term foreign policy. Look at our defense policy. That all gives me hope.

Second, alongside being the world’s largest democracy, we have cultivated a strategic culture used to plurality, to multipolarity. Traditional Indian strategic literature, stretching back to the 3rd century BCE, speaks not just of kingdoms, but of republics, of confederations, of city states, of how my neighbor’s neighbor is my friend. It shows India positively shaping our international system for over 2500 years. During that time, we’ve developed many good habits, which enable us to cope with new challenges and uncertainties.

Third, and most importantly, we have a long tradition (again stretching far back, through Nehru and all the way to Ashoka) of honing shared interests through dialogue with others. And if we can just tap the world’s strengths that way today, we can thrive. I expect significant challenges. I see us facing greater risks than ever before. I don’t envision easy times over the next few years. But overall, I sense India’s readiness to take up these challenges.