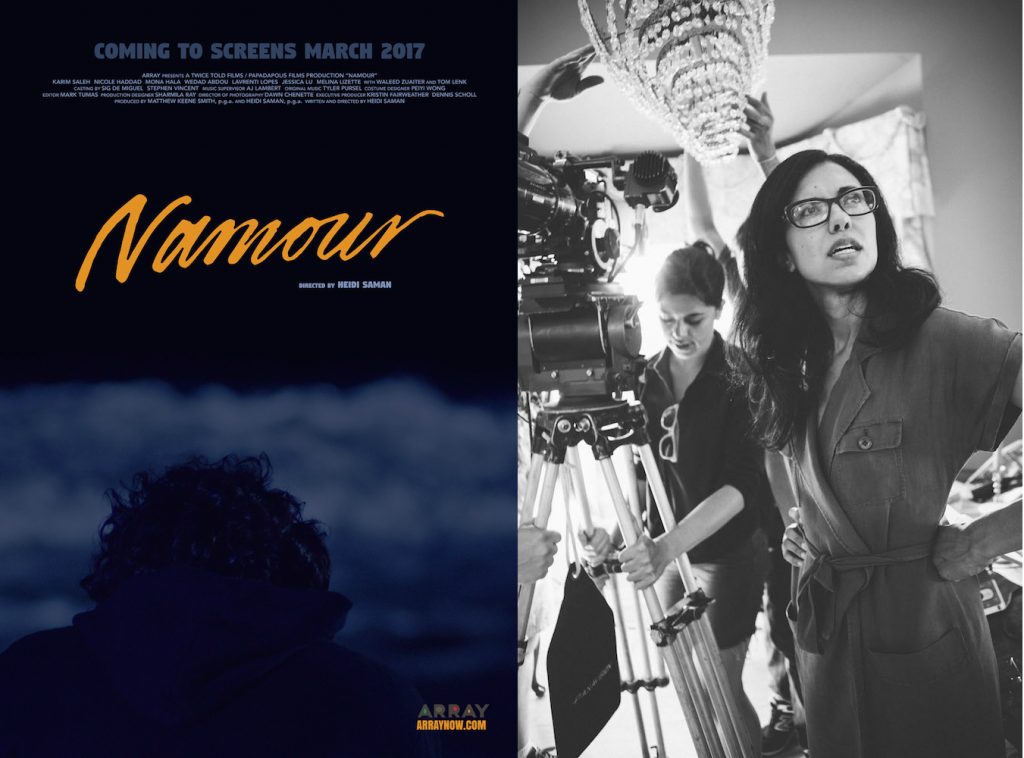

From a Kickstarter campaign in 2013, to its world premiere at the Los Angeles Film Festival in 2016, to hitting the big screen and Netflix in 2017, Heidi Saman’s debut feature film Namour has gone through one hell of a journey.

Filmmaker and associate producer at NPR’s “Fresh Air,” Heidi Saman set Namour in Los Angeles during the 2008 economic recession. Namour is a coming-of-age story that explores the cultural melting pot of L.A. through the immigrant lens and experiences.

Saman explores the intricacies of a dwindling sense of identity, belonging, culture, and an immigrant family struggling during a period of financial turmoil. Namour follows 20-something valet driver and son of Egyptian immigrants Steven Bassem, played by Karin Saleh, as he struggles to find the balance between a job he feels stuck in, and the demands of his family. Namour shows a raw depiction of a man finding and losing his way all at once.

After taking home the L.A. Muse Award for Namour in 2016, Saman’s film was acquired by award winning director Ava DuVernay’s film collective ARRAY. Founded in 2010 by DuVernay, ARRAY is an independent film distribution dedicated to the amplification of experiences by people of color and women filmmakers. Namour is the 15th feature acquisition by ARRAY.

Namour will be on a screening tour in select cities starting March 1, leading up to the film’s March 15 Netflix debut.

PAMELA AVILA: What inspired you to create Namour?

HEIDI SAMAN: I had been thinking about the recession of 2008-2009 and about how it might feel for someone who felt like they had opportunities ahead of them — maybe graduating from college — to confront the recession and the realities of that. I also saw people losing their jobs, I saw people losing their homes. At one point, my parents thought they might have to sell their house — and the house that we shoot in the film is actually my parents house.

You’ve spoken about the difficulties you had with finding investors for Namour. There was a lack of interest from investors for a myriad of reasons, one of them being the fact that your protagonists are Arab-Americans. Why was that an issue?

That was part of it, and part of it was also that if they were going to see an Arab-American in a major role, they wanted him to be doing very stereotypical things. I think what turned people off was the fact that this was an Arab-American guy who has no connection to terrorism, whose religion wasn’t foregrounded in his experience.

And I’m also talking about Arab investors. So I think it was a turnoff to them to see an Arab-American guy who wasn’t checking those boxes of terrorism, violence, religious oppression — all of those things. He’s just a guy who’s living his life and is trying to make his way and for whatever reason, that wasn’t appealing to them.

You know, this is an independent film, it’s fully independent, it’s a micro-budget film and it has so much of what I love about filmmaking in it. It’s cautious, it doesn’t hammer you over the head with how you should feel. It’s a film that’s supposed to make you feel rather than tell you how to feel. It doesn’t overly dictate itself. So everything was about that, about making that feeling even more of an experience.

Why did you choose the Los Angeles and Orange County setting?

I’m from the Orange County area. I’ve lived in Philadelphia for 13 years now, and I always feel like when you’re away from a city for a certain amount of time, you start to have a different perspective on it, or you’re able to observe it in a way that you’re not able to if you’ve been living there.

I also felt that the valet culture was such a specific part of Los Angeles. It’s this interesting sub-culture of L.A, that you can valet your car to do anything. So I thought it was an interesting thing to examine. I feel the valet culture is one space where you have classes intersecting. You know, where someone of a different class, middle class, working class, it doesn’t matter, is inhabiting someone’s car. It’s a very intimate space. You’re in their seat, you’re driving their car, you’re looking at their things maybe, and I just think there’s something weirdly intimate about it.

Aside from touching upon the intersectionality of different classes in Namour, through L.A’s valet culture, you’ve also said in past interviews that the “immigration experience in cinema is often illustrated in terms of binaries.” How does your work attempt to break those binaries and make them more nuanced?

I approach it first from my personal experience. I was born in this country, my parents were immigrants, and I felt like I belonged. I didn’t experience that feeling of, “I’m not supposed to be here,” or this division.

The script came from that experience of, “I’m not questioning whether or not I belong here, I just do.” That position is reflected in the fluidity with how the character interacts with his family. His mom speaks to him in Arabic and he responds in English. Even just the static camerawork, I wanted it to feel very meditative. That was a response to how immigrants are often filmed or how the immigrant story is often filmed — which is by a handheld camera. It’s gritty, it’s rough, they’re trying to make their way in this country — that’s one experience, but another experience is something that’s quite different. It doesn’t mean that you don’t experience hardship or that you don’t experience backlash, but your sense of self as a person doesn’t have to feel so bifurcated.

I understand what you mean. It makes me think of Aziz Ansari’s Master of None or Jane The Virgin with Gina Rodriguez, and how both shows approach a type of immigration experience in much more nuanced ways. Or the experiences of sons and daughter of immigrants. To me, both shows approach it in a more realistic manner than the stereotypical tropes of a lot of television shows or films.

Yeah, Master of None was such a great show. It’s interesting you mention that series, because the minute it came out, I just consumed it so quickly I didn’t realize how badly I wanted a series like that. Do you know what I mean? It felt so, I don’t know…

Familiar?

Yeah, it really did. I feel like the immigration experience is not often portrayed from that first generation, or the people who are here. Master of None was a nice response to that, or a nice reflection of that experience. I’d like to include my work more in that kind of category of work, about experiences that aren’t really questioning identity. The character can be Arab-American and it doesn’t have to be questioned. It’s just a part of who they are.

You have said that Namour is a film about “why life can feel like it’s passing us by.” Why is that?

Because I feel like that. It all goes by very fast, especially in your 20s. What you confront in your 20s is this possibility of going in every direction and the reality that you’re not going to take all of those opportunities. You’re just not. And I think there’s something sad about that. It’s your first confrontation with that truth. You won’t take all those opportunities — you’re going to take very few of them, because that’s just what life is. There’s nothing sad about that, but confronting it is sad, I think.

I totally feel that.

It feels like everything is happening but nothing is happening, because you’re just waiting. It’s a paradox of that age, between the endless possibilities and the fact that you’re stuck — because of money, because of your experience, or limited experience, or because you just don’t know what you want yet.

What do you share with Namour’s Steven Bassem?

Some of the hard facts are similar. My grandmother lived with my parents and my brother, so she had a big part in raising us, so Steven’s relationship with his grandmother is loosely based on my relationship with my grandmother. The house where we filmed was my parents house; it’s no longer their house but there’s a connection there. We come from the same background, my dad is Egyptian and my mom is Armenian-Lebanese. And I think the feeling, the tension of that age — that’s definitely me.

After you graduated from UCSD, you moved to Cairo to work as a freelance journalist. How did you decide to tell stories as a filmmaker rather than a journalist?

I still have one big foot in the world of journalism because of my day job at Fresh Air. But when I was working in Cairo, I was writing for an English language newspaper, and the English literacy rate in Egypt is not fantastic, so I really experienced how limited my reporting was. I could not access people who did not speak English or read in English, and it just wasn’t accessible. I think I got frustrated with how limiting that was, and my next thought was that images can overcome all of that. You can reach a much wider audience with film. It’s images, it’s audio, and there can be subtitles. And there are people that want to sit in a movie theatre, it’s entertainment. I think entertainment is a good way to include journalism. So I felt the limits of my journalism in Cairo.

How did you feel when the production company ARRAY approached you, interested in distributing Namour more widely?

I was very humbled, and grateful, and excited. They’re just building such a solid canon of films. I believe in what Ava DuVernay is doing, I believe in what [Executive Director] Tilane Jones, and [Marketing Director] Mercedes Cooper are doing. We need our own canon. I say our, meaning people of color. I like that they’ve expanded, I’m glad to be part of their canon because that’s how we move things, that’s how we start changing things.

Now that you’re weeks away from Namour’s premiere, how are you preparing for the big day?

This is a first for me. I never thought my film would be seen by potentially this many people, a click away and you can watch this film. I will be honest, I’m quite nervous.

It seems like it’s been a long journey.

It does, you’re right. I don’t know, I think any time you open yourself up to judgement and criticism, it’s very scary — but I’m also just glad people will have the potential to see it. I’m glad and grateful that’s a possibility. People watch Master of None and Jane the Virgin, and I just hope I can contribute to this kind of work that shows a more dynamic, comedic, sad — a more nuanced — version of our experiences. Because we need more images, we need those stories. We just need more stories of people of color.