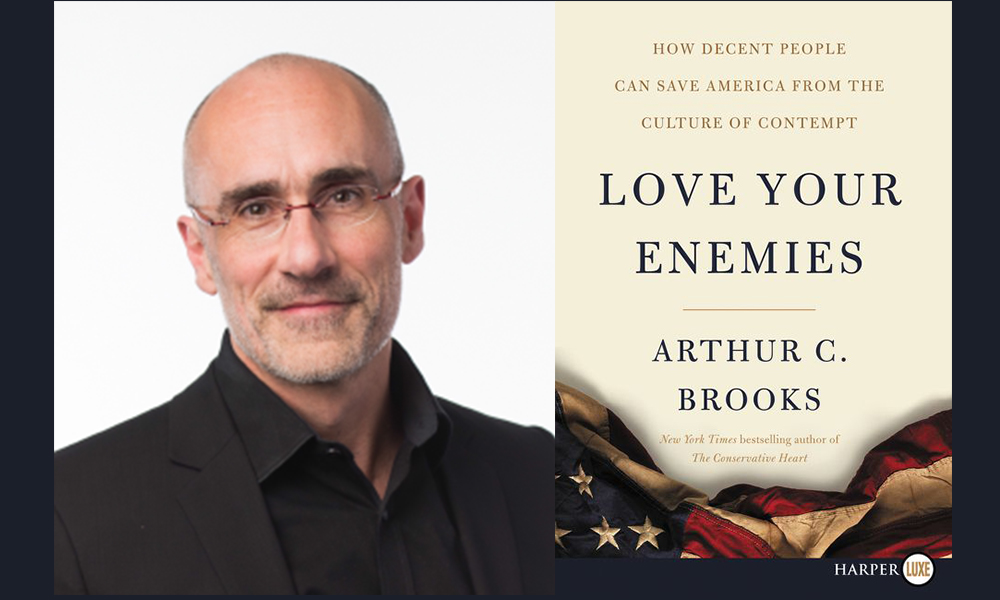

If love motivates “our” side, does that mean hatred inevitably motivates the “other” side? If you feel contemptuous towards some political rival, when should you work on changing that person, and when on first changing yourself? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Arthur C. Brooks. The present conversation focuses on Brooks’s book Love Your Enemies: How Decent People Can Save America from the Culture of Contempt. Brooks is president of the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), a public-policy think tank in Washington, D.C. In the summer of 2019, Brooks will join the faculty of the Harvard Kennedy School and Harvard Business School. Before becoming president of AEI, Brooks was a professor of Business and Government at Syracuse University. Prior to his work in academia and public policy, he spent 12 years as a classical musician in the United States and Spain. Brooks has published dozens of academic journal articles, and the textbook Social Entrepreneurship. His feature-length documentary The Pursuit was released this spring.

¤

ANDY FITCH: This book’s subtitle could appear to offer some categorical distinction between “decent” and “indecent” Americans. And your book does at times seem to make the quantitative case that a critical mass of center-right and center-left moderates need to come together to check partisan extremists on both sides. But this subtitle also could suggest a more qualitative, aspirational appeal to a much broader range of Americans to become their own most decent selves — so recognizing our collective contribution to present-day partisan dysfunctionality, and charting personalized steps toward changing that behavior. So could we start with you talking through when you do see yourself making a quantitative argument against certain types of Americans, and when a qualitative appeal to all Americans?

ARTHUR C. BROOKS: That’s more or less exactly what went through my head while I put this book together, so thank you. And my own book of course cites Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People — which, for an academic, might sound like me praising Goodnight Moon as my favorite book [Laughter]. But Carnegie’s very beautiful book has these timeless ideas about personal revolution, and I wanted my own book to call for that kind of revolution. Carnegie basically says you always should appeal to others’ better nature. So with my own book, and its talk of “decent people,” I do want readers to think: I am a decent person, but I also can do better. I mean I guess I could have separated the sheep from the goats here. I have my own subjective opinions, just like you do. But I took it as my goal to make people want to be more decent. I tried to outline what I think you need to do to become more decent. So “decency” here does mean something aspirational, something that can help to cure our culture of contempt.

Well in terms of providing a diagnostic for this pervasive presence of contempt in contemporary US political culture, could we start from a working definition of “contempt,” then sketch how you see it spreading? Here I would note, for example, that defining contempt as “anger mixed with disgust” seems to me quite different from defining contempt as the expression of another’s worthlessness. I would ask if you prioritize a present-day vector of Americans treating others contemptuously, or of Americans feeling treated contemptuously. I’d ask how public condemnation of one’s personal character might provide a different experience of contempt than, say, having one’s community systematically marginalized for the past several generations. And so I’d ask to what extent the overall amount of contempt has grown in our society, and to what extent we’ve seen something more like a redistribution of who gets to express contempt towards whom, through which channels. So however you want within that wider context, could you introduce the crucial role that contempt plays in this book’s explanatory account?

Sure, so the answer starts with a paper I read in 2014 by the Northwestern University psychologist Adam Waytz. Waytz’s paper picked up the concept of “motive-attribution asymmetry,” a pretty basic phenomenon actually, but given a fancy academic title (because we academics need these in order to get tenure). Waytz gives this very, very clever formulation of an asymmetry in which people feel that their own group is motivated by love, but that some opposing group is motivated by hatred. This happens all the time. And of course, if you think about it, both sides can’t be right (though they could both be wrong).

You see this in the Palestinian-Israeli dispute, the Rwandan genocide, the Balkan conflicts. But Waytz found that, for the first time since we had started keeping records, the levels of motive-attribution asymmetry between Democrats and Republicans had gotten as high as the rates between Israelis and Palestinians. That means we’ve reached a pretty catastrophic level of dehumanizing each other along partisan lines — so that, for example, the characteristic that people most don’t want to see in their child’s spouse has become belonging to the opposite political party. Why? Because it suggests this prima facie evidence of terrible character. And not long ago, many of us would have considered that kind of judgement unthinkable. But now, if your daughter comes home and tells your Democrat family she wants to marry this Republican, people might react as if the guy has some glaring pornography addiction, or has shown some serious moral deficiency.

Now, that type of response feels very different than just having a policy disagreement with somebody. If you think of yourself as motivated by love for humanity, what do you feel when you encounter someone motivated by hatred? According to John Haidt and a lot of other social scientists I work with, you feel disgust. You actually think of the other side as a pathogen, and humans naturally react to pathogens with disgust. We defend ourselves this way. When you step into something that stinks, you feel disgust, right? And we feel a similar kind of disgust today about certain other people, filthy people, contaminated people who could actually hurt us. But somebody with values orthogonal to your own also can become that person.

So now, to connect this back to how psychologists think about our disgust for another person: when you mix disgust with the hot emotion of anger, then you get contempt. Contempt comes about through this weird mix, kind of like mixing bleach and ammonia. Each on its own is pretty innocuous, but together they become chlorine gas — just like taking anger towards a person and mixing in disgust can make for a quite deadly combination.

And then alongside psychology, we can look at how philosophers characterize contempt — basically as the conviction of somebody’s utter worthlessness. Something that disgusts you has no inherent value. Anger about something might make you want to change it, but if we add in disgust, then it just becomes worthless. So Arthur Schopenhauer describes contempt as the conviction of the utter worthlessness of another human being. So now, moving back to our present, and to practical applications of this idea of contempt…first I don’t want to suggest that a random Democrat and Republican picked off the street should operate the same way that a married couple does. But marriage does create this very interesting ecosystem or laboratory for understanding human relations.

So I’ve talked, a number of times, to John Gottman, a world-renowned expert on marital reconciliation. He runs the Gottman Marriage Laboratory, and within a one-hour counseling session he can predict with 94 percent accuracy whether a couple will get divorced in the next three years. And what does Gottman look for? He says that he looks for physical expressions of contempt: for sarcasm, derision, dismissiveness, eye rolling. Eye rolling is a biggie, right?

When you treat somebody these ways, you basically suggest that you would shun this person if you hadn’t gotten married to them — which already sounds pretty extreme. And then with political disagreements, of course, the best way to make a permanent enemy is to act as if you never have heard something so stupid, or encountered somebody so worthless. And that kind of expression of contempt basically characterizes our current political discourse.

But now here John Gottman’s work really gets fascinating for me, because he says we often treat others with contempt, but don’t hold them in contempt. We actually might love them. We might create our own big problem which basically comes down to a bad habit of communicating contempt. Couples can get into a self-reinforcing cycle where one person speaks dismissively about the other, and the other rolls her eyes, and the first person makes a sarcastic joke, and pretty soon they’re both treating each other as disgusting, worthless beings — and before long they get divorced even though they still love each other. So I said: “John, what do we need to do differently in this situation?” And he told me: “You have to break this habit of expressing contempt,” and hence my book was born.

And here to continue connecting broader motive-attribution dynamics to some of our most intimate relationships, I think of this book’s anecdotal encounter with a stranger who (perhaps sensing an opportunity for partisan bonding) rails against “stupid and evil” progressive intellectuals — with you sharing certain policy preferences with this person, but nonetheless thinking: That’s my family she’s talking about. Here your own idiosyncratic amalgamation of identities does stand out: as, say, a Seattle-born, Dalai Lama-befriending, long-term professional artist and academic who nonetheless endorses a classically liberal economic approach typically associated with today’s conservatives. At the same time, you tell us that you often face large audiences in which every single individual acknowledges having a close family member or friend on the opposite side of some presumed political spectrum. At the same time, you tell us that, just since the 2016 election, one-sixth of Americans have found it impossible to maintain at least one close personal relationship which previously crossed these partisan divides. So what do you consider relatively unique, and what relatively universal, about your own lived experience with political cross-cutting?

So I do have an eclectic background. When I still taught at Syracuse, I went to see George W. Bush once, to talk about a book I’d written. He walked into the Roosevelt Room reading my bio, which mentioned my work as a professor and economist, and as a professional French horn player in Barcelona, and as a combat analyst for the RAND Corporation — and he looked up and said: “I’m just going to call you a weird dude.” Over the years we became friends, and once during an interview I mentioned that this wasn’t the first time he had called me a weird dude. He just looked at me for a minute, and then said: “I rest my case” [Laughter]. He’s unbelievably funny. But he also had a point. When you do a lot of different things, you do become sort of unclassifiable. I mean, I graduated from correspondence school a month before my 30th birthday, after dropping out of college to play in the Barcelona orchestra (and then I became a professor).

But as you said, what would stand out most to many people in this kind of intellectual-artistic-hipster background would come from my belief that traditionally conservative economic policies work best — and work best for achieving very, very progressive moral and social objectives. My own research and reading of history tells me that classically liberal economic policy, and American leadership in foreign affairs, really have been our most successful ways to attain those goals. Of course our policies have been imperfect. Of course we could do better. But I still consider this liberal approach the best one that we’ve developed so far. At the same time, I have tons of affection for individuals with all kinds of different beliefs, because I get these people. They’ve all become part of my tribe at this point. I mean, I wrote the book as a self-improvement manual (for myself), and it really did work that way. It clarified what I had to stop doing, what I had to start doing, and how then to share that with everybody from my relatively public position.

I’ve started noticing that when I go to some conservative-policy function, and see the one big lefty in the room looking very uncomfortable, I now immediately gravitate to that person and try to make him as comfortable as I can, and to draw him out and thank him for constructively disagreeing, and I ask him to keep up his courage and the whole thing, right? So what most discourages me right now is when we somehow consider it morally permissible to “deplatform” conservatives on college campuses, or to stand up at some Trump rally and declare all progressives “enemies of the people.” That whole part of our culture of contempt just makes me want to keep improving and become part of the solution — because fundamentally I do have half of myself in one tribe and half of myself in the other. Even when this book describes different tribes having different moral dimensions, I know that I myself have left-wing moral instincts. Loyalty doesn’t do much for me. Purity doesn’t do much for me. I feel no natural respect for authority. But I still recognize that conservative ways of doing things also have real virtues, and sometimes appeal to me intellectually even if they don’t instinctively. So I want to combine all of these different impulses, but I also see how hard that becomes when we get held hostage by motive-attribution asymmetry.

Yeah and in terms of potentially overcoming such tendencies, Love Your Enemies also laments the impoverished definitions of love that circulate in contemporary American culture, and points to any number of broader social contexts in which a reformulated conception of love could provide a crucial catalyzing force. But first still sticking to the personal, let’s say we acknowledge your own good fortune to have grown up infused by a foundational, conscious, articulate, filial love distinctly equipped to encourage empathic engagement rather than defensive rigidity, even when it comes to acute disagreements. Do you think of us all as possessing the innate capacity to practice this kind of love? Or when might it be unfair to ask one’s fellow citizens to call on a resource they just don’t have, and that maybe they just can’t cultivate on their own — more like Mitt Romney recommending that young people ask their parents for a loan to fund their startups?

If I didn’t believe that everybody has the capacity for this kind of love, I wouldn’t have bothered writing the book. And I include the whole section on bridging social capital (a kind of wonky academic concept) because I want to show how it can make getting outside your own tribe so satisfying. When I talk to young people, especially on campuses, I try to stress this incredible moral satisfaction that comes from being persuadable, from being able to say: “Good point. I guess I should rethink that.” I try to present humility as a heavenly virtue, and heavenly virtues as satisfying — and as the opposite of the deadly sin of pride, which sometimes can give you a little bit of satisfaction, but which never can give your heart what it truly desires.

Diversity matters here, too — because that kind of cultural exposure helps us develop the capacity to understand others more wholly, to open ourselves to this bigger human family. When you silo yourself off in terms of your neighborhood, church, school, social-media experiences, you don’t only lose out on cultivating empathy. You lose out on just a basic understanding of things. You never exercise those muscles if you isolate yourself.

So I do consider myself the luckiest guy I know, precisely because I grew up Catholic in Seattle, and then lived overseas, and then married a girl from an atheist family. That all made it possible for me to relate to more and more people — not everybody of course (I’m not perfect, of course). And we all can do more of this, and need to if we want to live the fullest possible lives.

Returning now to a broader social diagnostic, when you describe us “being driven apart, which is the last thing we need in what is a fragile moment for our country,” the Creative Writing professor in me wants to ask you to push beyond the passive voice, and to delineate who drives us apart at present, which factors make this moment so fragile, what precisely we need instead. And your analogies to addiction and your analyses of demand-driven trends again pose important questions about how individual / collective agency and technological convergences and unintended consequences all play their part. So where might you point most directly to specific causal forces shaping these present-day dynamics you find so problematic?

One of the biggest culprits behind our divisions is what I call the “outrage industrial complex.” A whole set of perverse incentives leads many people in positions of influence (whether on cable news, in op-ed columns, on campuses, or on Twitter) to cater to our very worst impulses — demonizing the “other side,” while affirming all of our own views. This does not represent mainstream thinking at all, according to the data. However, it is temporarily satisfying and quite addictive to hear that you are right while they are stupid and evil. And by paying attention to these messages, we send market signals that reward these radical and destructive voices. Ultimately, change starts with your favorite columnist and you: by which I mean, by you deciding not to read the column that appeals to your worst impulses, and by you deciding to have conversations with your neighbors rather than getting wrapped around the axle about who said what on social media.

And so how might we then come to see ever-present temptations to contempt as in fact fortuitous opportunities to depart from contempt: to forgo changing others and focus on changing oneself, to cultivate personal virtue rather than indulging in mob-like mayhem? And how might you see your own thinking here as arising out of a Catholic meditative (in the literary / reflective sense) tradition itself stemming from Stoic and Socratic practices — as well as arising out of Buddhist principles?

I want this whole book really to raise that first question. And as you know, I have an extremely syncretic range of religious and philosophical and personal influences. I have a piece coming out in the July Atlantic about how to go from strength to strength in life — and how, as someone older than 50, to look forward to the coming decades. How do you do that?

For me, a teacher in Southern India, a guru named Sri Nochur Venkataraman, has really helped a lot to clarify this key point (actually more Hindu and Christian than Buddhist) about the sacredness of suffering. We have a tendency to avoid all pathogens. If our friend catches the flu, we don’t let him cough in our face. But when I talk to Marines (so here obviously changing my point of reference), when Marines in Fallujah get fired on, they run towards the fire. These Marines have been trained to recognize that they have the best chance of winning that firefight and of surviving if they rush towards the fire rather than away from it.

Or I gave the BYU commencement address two weeks ago, and of course nobody ever says: “Oh great, look, we have Mormons on the porch! They want to proselytize to us.” Instead you pretend you’re not home, right? But many Mormon missionaries describe being filled with joy. They actually lean into the pathogen. The very resistance they encounter becomes the source of their deliverance. They have the truth. They want to live the truth and express the truth and share the truth. And you can’t do that in a satisfying and meaningful way unless you face some resistance. Our lives just don’t work like that.

And so I have learned a lot from teachers of Eastern religions. But as you said, a lot of this extremely optimistic thinking also comes from ancient Christian scripture, and of course Thomas Aquinas took much of it from Aristotle and from the Stoics. You get this basic idea that nobody really wants a life lacking all resistance — that when there’s no grit in the system you just go crazy, that you need to find the things that are wrong in yourself and in the world, and confront them in ways that reflect the best possible person inside of you (and in so doing, you will become that person, and actually accomplish your own transformation). That makes your own life a moral enterprise, and makes you the entrepreneur.

So in the case of contempt, you should look for all its different manifestations in your life and your society and your world, and use these moments as your opportunities to answer hatred with love. And answering hatred with love has at least three guaranteed advantages. First of all, you yourself will become more persuasive. Martin Luther King, for example, in a beautiful 1967 sermon on Matthew 5:44, said that only when I love my enemies, only when I love a man can I redeem him. I consider that incredibly practical teaching. If you want to fail at persuading somebody, then just look down your nose at them, or virtue-signal. If you want to succeed at persuading them (which we don’t do very well these days), then you actually need to love them.

Second of all, answering hatred with love will just flat out make you happier. This book presents the brain-science research that proves this claim. When you treat others with contempt you lower your long-term happiness in exchange for some minor satisfaction. It’s not so different from taking meth. Every hit of meth gives you both short-term satisfaction and long-term unhappiness — and the same with contempt.

Third, if you respond to hatred with love you also can change somebody else’s heart — at least from time to time. No guarantees, right? But my book discusses this person from Texas who writes a long letter basically calling me a terrible fraud. And when I write back with gratitude, thanking him for reading my book so carefully, he reflects his own form of gratitude, and invites me to dinner. You just never know what might change somebody’s heart like that.

And finally, I’d add that when you respond to hatred with love, you contribute in your own small way to helping bring this country together. You become part of the solution, not part of the problem. Whether you show this love in some public discussion, or some interaction within your family or your community or your workplace, it gets noticed, and it helps to set the tone. So I consider this type of loving response at least a win-win-win, and maybe even a quadruple win — with literally no downside except a hit of dopamine and some quiet satisfaction.

So here, for one specific social context, when you mention both speaking on college campuses and writing about life after 50, I think of two social groups increasingly characterized, in fact, by the contempt that they express towards each other: so-called college-aged people, and retirees. And I picture both groups as much more likely to find themselves saturated in mono-cultural experience than, say, full-time working adults (as millennials start a new phase of life further away from home, and as unprecedented numbers of able-bodied retirees face unprecedentedly long and undefined time spans ahead in which to figure out new social roles). But so my broader question becomes: when do you find it useful not just to track an aggregate rise in national partisanship, but to track particular cravings for social bonding, manifesting in particular demographic groups, facilitated by particular socio-technological transformations? How might a slightly less moralizing, slightly more circumstantial diagnostic lend itself to your pragmatic formulations on action determining attitude, on diversified social encounters being our best way to instill empathy and compassion? Alongside the struggle in our individual hearts, when should we blame “society” for our contemptuous behavior — if only to coax forth newly proactive modes of demographic integration fitting our present?

Well that touches on one big criticism this book has received, which basically says: “You’re giving personal advice to people who live under the cloud of structural racism.” Or here you could substitute patriarchy or homophobia, and you of course could include the language of intersectionality (especially on a college campus). And the right has its own equivalent language about being victimized by institutions and the media — about why the only appropriate response involves expressing contempt right back to these institutions and to the individuals representative of these institutions.

Again, I get all of those arguments. I might have a beef with some of these arguments, but I can hear them out. At the same time, I often respond by asking people: “What’s your ultimate goal?” I’ll quote Martin Luther King’s statement that certain ideas might deserve your contempt, but individual people never deserve your contempt. And then I’ll follow up by asking: “What precisely do you want to do to this person? Would you like to sneak into their house and harm them while they sleep?” Everyone says: “No, of course not.” I’ll say: “Well, do you want to imprison them for their ideas?” “No.” “Do you want to kick them out of this country?” “No, no.” “So what do you want?” And most people answer: “I want them to think and behave differently.” So then I’ll say: “Well, how is your hate working out for that? Has that gotten you anywhere near your goal?” If you want the fleeting satisfaction of feeling virtuous and firing up your side, maybe you can succeed this way. But if you really want people to think and act differently, it probably doesn’t help much to have hatred in your toolkit.

No one in human history has insulted their rival into agreement. Again, is it fair for us to have to operate within these laws? Who knows? That’s above my pay grade. Ask the pope. Ask the Dalai Lama. All I can tell you is that the insulting approach never worked for me, and that shifting to this more constructive argumentative style only has made my work better and my life happier.

Look, a ton of stuff still bugs me, right? And of course many of us have good reason to feel that we belong to particular groups that have been unfairly kept out of power. But that just takes me back to the basic question: what social objective do you have? What moral objective do you have? What practical professional objectives do you have? You don’t serve any of these best with hatred.

Along related lines, you call upon Americans not to choose identity-based politics, though you acknowledge that some of us always have had identity categories (and all of their problematic consequences) forced upon us much more than others. So how would you calibrate your recommendation for us all to shake hands (and disagree constructively) with a recognition that we still cannot do so from a level playing field? And if advocates for freedom and opportunity (for all) historically have been characterized as contemptuous of “the American way of life,” to what extent should we assume that praiseworthy present-day efforts to expand freedom and opportunity will likewise get accused of trafficking in contempt? When might well-intentioned efforts to diminish contempt impede desperately needed efforts to promote social change?

So we can handle that friction. We do so not by disagreeing less, but by disagreeing better. I do not call specifically for peace. And of course nonviolent conflict itself can have a huge impact. King did not call on us to acquiesce, to shake hands and get along. King did not fight for agreement. I don’t either. But I do believe that disagreement gets us nowhere until we can push beyond contempt. Contemptuous disagreement just destroys. It just tears down — whereas disagreeing constructively actually can produce positive social change. I mean, I have pretty strong views about the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. In certain cases, I do consider one side so much more right than the other. But I also can see why that conflict never can resolve itself so long as motive-attribution asymmetry shapes everybody’s perception on every side.

And similarly, in an American context, if you want to play the part of social-justice warrior (either on the left or the right), if your ultimate goal is to express how pissed you are, how virtuous you are, okay. But if you hope to change society, you’ll have to find some more effective approach. And you probably can’t get far enough with agreement alone, or certainly with civility, which I consider a garbage standard. You’ll probably need to tap the kind of respect that really only comes from constructive disagreement — not from saying “I hate you,” but “I’ll do my best to understand you, and I hope you’ll try to do the same.” That’s actually as vigorous as we get in our politics. That takes so much more work than marching does. And that commitment to persuasion (and to yourself being persuadable) ultimately can win the day. Martin Luther King, one of American history’s greatest leaders, died with roughly 25 percent popularity. Today he’s at 95 percent.

Here returning then to spiritual precedent (as King himself of course did), could we also start to explore more directly the sometimes quite intimate, sometimes quite galvanizing “I-Thou” quality your book creates? And of course the book often reinforces this “I-You” dynamic by positing some triangulated third party, some bully, or partisan, or hater, or manipulator, or breaker, or (problematically homogenizing) bonder. So it wouldn’t be hard to follow up on your quite useful account of motive-attribution asymmetry, for example, by asking why you yourself don’t seek to humanize these supposed contempt-mongers — frequently posited but never fully fleshed out. But why was right now, with this book, not the appropriate time to make that particular empathic case? Or how do you in fact see us most proactively, most constructively connecting to our more contemptuous, more partisan fellow citizens?

Great question. That suggests a basic inconsistency. Shouldn’t I refrain from expressing contempt toward the contempter? Okay, I can say a couple things about that. I gave a related speech at UVA the other day, and afterwards this lady said: “I get it. I get it. But I just don’t know how to love Donald Trump.” And I told her: “You don’t have to, because Donald Trump is an abstraction to you. But do you know who’s not an abstraction to you? Your sister-in-law who loves Donald Trump.”

I mean, I would recommend that you don’t anguish yourself, and go to bed tossing and turning, thinking about how much you hate Donald Trump (or about how you need to work out some grand moral strategy so that you can love Donald Trump). The bigger problem in your life might come from hating real people who love Donald Trump. So in some ways the contempter, the outrage industrial complex — those are just abstractions for most of us. Again, instead of directing our contempt towards them, we might improve our situation by simply disregarding them, and giving them less of a presence in our consciousness. You don’t get much out of personalizing Donald Trump this way. You can’t help having an asymmetric relationship. Donald Trump can give no satisfaction regardless of if you express love or hatred for him, right? So why dwell on those abstractions that only can have a negative impact on us? When you want to do a loving-kindness meditation, okay fine: if you advance far enough, years into your meditation practice, then include Donald Trump.

Similarly, in terms of training each other to spar constructively, in terms of bringing out the best in one’s conversational rival, I think of this book’s frequent invocation of the “you” (along the lines of “Have you been told…. that if you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention?”). I note that Uncle Sam-style finger-pointing (in the most positive sense of this term) structures Love Your Enemies from the start, with even that title a bracing imperative appeal far different from some more sappy, memoir-like “I have loved my enemies.” Could you describe writing to this “you”: perhaps as a strategic means of avoiding armchair audiences, perhaps again in broader spiritual terms, perhaps as a way to unleash the rhetorical power of stories (here your readers’) while still remaining skeptical about the explanatory potential of the anecdotal story?

It’s definitely weird for somebody who does social science to adopt the second-person-singular (it’s weird enough to adopt the second-person-plural). But I really did want to take this book to you, and set it in your lap, and to say: “I wrote this for you.” Of course I actually wrote it for myself, but now I want to share it with you, and to make you really conscious about that gesture. It just gets people’s attention more. And I understand why most scholarship doesn’t work this way. I mean, most social-science writing uses the passive voice — to get as far away from individual human experience as possible. For myself, I promise never to write a memoir. Shoot me before I write a memoir. Nobody needs a memoir of Arthur Brooks’s life. You only need to hear about my cognitions and experiences and views insofar as these inform the thinking I hope to get across.

So yes, writing to a “you” was a very conscious act. I told my editor: “I want the reader to get my full attention.” And sometimes that also means telling stories about other people. My whole rhetorical style comes out of the “Let me tell you about this person” approach. I do 175 speeches a year. I can’t just offer my audience some desiccated ideas, some disembodied concepts. And for this book I wanted to focus 10 percent on problems, 90 percent on solutions. But I couldn’t do that in the third person, with a bunch of vague platitudes about how to improve institutions to produce better policy decisions and outcomes. Instead, I needed to sit down with my reader. I needed to establish a real conversation. I wanted you to feel like the only person sitting directly across the table from me, hearing how I really sound.

So within this type of more cordial and intimate chat, let’s say the optimist in me wants to believe that, amid our bitterly polarized present, we now see more low-hanging fruit than ever in terms of smart consensus-building policy initiatives easily within reach, if we just can shake our most constrictive partisan tendencies. Let’s say I express the hope that fair-minded Americans with whatever political affiliations never have had such strong incentive to come together and reinforce shared baseline principles for how a democratic society should operate. Where do you see significant opportunities for some sort of pragmatic coalition of post-hyper-partisans to emerge, either at a foundational procedural / institutional level for American democracy, or on specific shorter-term issues? What inevitable snags would such a coalition need to surmount? And given your own political vision, what most persuasive case could you make that partisan dysfunctionality prevents us from tapping a competitive excellence in policy-making on which our entire American experiment is premised?

So I tend to write institutional books, books about how to fix society with better capitalism, with better politicians, with better policy. But as I started imaging this particular book on getting people together to have these experiences of our common humanity and all of that, I thought: You know what? This one isn’t an institutional book. And reading Martin Luther King right then clarified for me that King himself was not an institutionalist. I mean, everybody remembers this amazing civil-rights advocate leading to the creation of a Civil Rights Division within the Justice Department or something. But King called us to a much more personal revolution. Christ called people to personal revolution. All constructive social movements actually come about through personal revolutions — and then institutions follow individuals. That might sound like some Ayn Randian conclusion. But the Dalai Lama actually taught me something similar: heal your heart. If each of us does that, then we will have created the unstoppable demand for the change we need. Successful social movements work that way. The personal revolution they bring about can feel quite satisfying. And that’s when people demand different outcomes in their society. That’s what creates spontaneous parades.

One of the strongest and weakest features in democratic capitalist societies comes from leaders almost never leading. They see a parade going down the street, and they think: I’ve got to go jump in front of that parade, because it needs a good leader. And then they basically end up where this parade has pushed them. So when I look at Donald Trump or Bernie Sanders, I see the consequences, not the causes, of our own decision-making. And when I think about how we typically make political decisions today, I want to harness some sense of hunger.

You know, drug-and-alcohol recovery programs work by stimulating your hunger to have a better life. We might give somebody ideas all day long on how to stop using opiates, but until that person feels their own intense desire for personal change it just won’t happen. That’s why, for me, institutions matter, and political leaders matter, but they always need a much more personal revolution driving them.

Sure, and alongside harnessing hunger, harnessing desire, could we talk about harnessing an even more potentially positive force like joy? Joy doesn’t have the same scriptural or moral alibi as love. Joy seems more precarious than health or healing. Joy doesn’t have the same respectable clout in social science or in most public debates. So what has it meant for you to incorporate joy (not just love) into a far-reaching political vision?

Here I’d start by distinguishing between joy and happiness. That might depend on whether we start from a religious or secular context. Psychologists and theologians define joy differently. The Christian theologians typically describe joy as this tiny little window on heaven which then quickly closes up. Surprised by Joy, C.S. Lewis’s memoir, discusses these moments when you say: “Oh, heaven feels like that. Oh, now it’s gone.” He thinks of joy that way, whereas psychologists describe something more like an enduring ambiance which may not even include conscious happiness. And in between those two accounts, I guess I don’t yet have any clear bottom line. I haven’t written about joy much. I think of love as my beat. I used to consider happiness my beat, but actually love (as defined by Aquinas, as willing the good of the other) fits me better.

That type of interpersonally empowering love offers our best answer to hate. I want to keep exploring that tough, bracing, subversive love, in all its contours, for the rest of my life. And even if this particular book focuses on America’s contempt problem, I hope to make the bigger point that we actually suffer from a love crisis. This contemporary contempt problem has some pretty specific macro-economic roots. I mean, financial crises basically always breed populism, because of the uneven economic growth that follows them. You inevitably get a William Jennings Bryan or a Bernie Sanders, more or less. But our country’s love crisis could have an even more corrosive long-term impact. Some of my newer work tracks this huge love crisis (with even a romantic-love crisis) among young people. People in their twenties today are 30 percent less likely to describe themselves as “in love” than people were during my twenties.

You see this remarkable lukewarm-ness among people in college today. No way will they describe themselves as in love. And even young people without social strictures, with no traditional religious moorings, have much less sex — again because of this lukewarm tendency. And we could consider this just one branch of the real love crisis that will impact joy as well. I just think of us as built for love, and without love I don’t see how anything turns out good. So I would situate this contempt crisis as something like a short-term flare-up, but indicating this much more serious autoimmune disorder: this crisis of love.