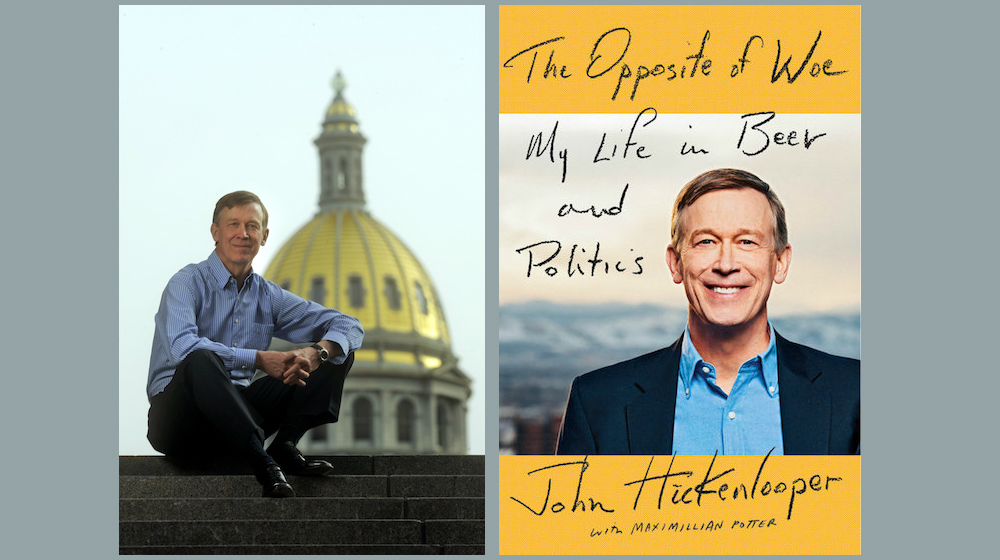

How might those of us who never ran for class president eventually find our way to political office? How might what you tell your window reflection eventually help to harness a much broader constituency’s collective aspirations? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper. This present conversation (transcribed by Christopher Raguz) focuses on Governor Hickenlooper’s The Opposite of Woe: My Life in Beer and Politics. Hickenlooper is a former geologist and entrepreneur. In 2007, he was reelected mayor of Denver by close to 90%. In 2011, he became the first Denver mayor elected governor in more than a century (he also became the first brewer elected to a governor’s office since Sam Adams in 1792). Hickenlooper considers governors, far more than Congress, crucial for revitalizing American political culture.

¤

ANDY FITCH: I see a lot of nonfiction first-person manuscripts, and I almost always ask the author: aside from documenting the fact that this random experience happened in your life, why do you want to share this particular side of yourself with readers? The Opposite of Woe stands out, for instance, for presenting an “I” with certain traits that most political figures probably would fear having associated with themselves. So could we start from one of this book’s emotional centers, with you, as a boy, hearing about your dad’s death and running out to a friend’s party, obviously struggling to process any number of conflicted feelings, with your ex-wife later suggesting (as your book repeats several times) that half of your heart closed down when your dad died, and that your dispassionate, analytic, facts-over-feelings approach makes you (at one point at least) perhaps not an ideal romantic partner, but maybe an ideal pragmatic governor? What would you characterize as most distinctive about how that dispassionate perspective shapes your connection to your constituents? When might it work better for a political leader to partially connect with people from many different sides, rather than to connect more fully with a much more narrow range of the electorate? Or how else might you most proactively rewrite clichés about bleeding-heart liberals, here by presenting yourself as a half-a-heart liberal?

JOHN HICKENLOOPER: Writing this book made me spend time looking at where I came from in greater depth than ever before. My dad died when I was very young. I never got to hear any of his stories except third-hand. That created this vacuum throughout my whole life. That’s what really compelled me. By the time I’d reached third grade, with my father sick and dying, the greatest gift anybody could give my mother was laundry service. She’d wake up two or three times to sweat-soaked sheets each night.

And I responded to all of that by becoming this total nerd-jerk who everyone disliked. My mom helped me work through that by making me think about how my behavior affected others. She had this chart. Did I say anything mean behind someone’s back? Did I interrupt anyone? Did I ask somebody about their day, or their life? She asked five or six questions like that every single day. And what I didn’t even get to in the book, what I didn’t really think through until after writing it, was how being the brunt of all those jokes, being the kid everybody teased about his name, the person just completely marginalized…only with this book already at the publisher did I realize how those experiences had compelled me into public service.

That first-hand experience means that while I don’t come across as a bleeding-heart liberal, while my speeches might emphasize pragmatic action, it all comes from this deep emotional connection. I feel that connection with workers when they themselves feel left behind, with nobody taking the time to really offer retraining, with people just saying “How could these factory workers possibly figure out this new technology?” Well, those factory workers are pretty good on their cellphones, which are little computers, right? But anyway, sometimes you write a book for one reason, but then get lucky, and you actually learn lessons from the writing. And for me (still this very frugal, very pragmatic governor, still very disciplined and not just throwing money at every new problem that engages my emotions), writing this book gave me fresh clarity on who I really cared about.

In a couple weeks, I’ll receive an award from One Colorado, one of our large LGBTQ organizations. They’ve laid out all the things we’ve done in the mayor’s office and the governor’s office over the past 15 years for gay communities. But this goes back much further, to 1990, when our first restaurant, Wynkoop Brewery, promoted our bar manager, who was gay, to become general manager, because he was clearly the best — and we had customers complain about it. But we never even hesitated. We had that sense of America as a place of equal opportunity, where we all create our own version of the American dream. That has to apply to everybody.

And when I stumbled on that “half-a-heart” phrase, just to clarify: this book certainly doesn’t present some narrow, rigid, constricted character. Readers might find themselves surprised to see this straight-shooting Western governor as a Wesleyan-trained flower child, or ending up at New York get-togethers with Tennessee Williams and James Agee, or later appearing in Kurt Vonnegut’s last novel, or later still becoming perhaps the only elected official to date to describe someone as “having an Elvis Costello vibe.” And since you present your young self as so enamored with one almost-girlfriend’s “centeredness,” could we start to trace the range of experience that constitutes your own gradual centering — as somebody who, at various points, has taken up the roles of hopeless romantic, soul searcher, artistic type, geologist, engineer, entrepreneur, urban developer, eventually political leader? Most broadly to start, what type of center have you stitched together by harnessing all these various parts of yourself? How has this diverse range of personal experience shaped your mode of quite dispassionate or disciplined, but also impassioned and innovative middle-path politics? And how might that middle path differ from just being some median point or muddled average between more familiar conservative and liberal extremes? How has being a “centered” elected official differed for you from just being statistically “centrist”?

I wish I could give an easy answer. I mean, writing this book meant figuring out how to describe that evolution. It’s not entirely unique, but it’s certainly unusual that, for so long, the notion of running for office just never entered my mind. I had never asked any friend: “Should I run for student council? Should I try to get involved in somebody’s campaign?” Those questions just had no relevance to me. So I did many things (which, by the way, I recount in the book) that don’t really help to build your political resume [Laughter]. But I didn’t want to hide that. I want this book most of all to encourage other people who have never thought about politics. I want them to say: “Ah, if this guy did it, maybe I could do it.”

My friend in Boston, a child psychiatrist named Nick Browning, told me as I wrote the book that when you’re a boy and your father dies, in some ways you have to raise yourself. Nick said that this can take many forms. For a lot of people it means needing to find some measure of their self-worth. It means needing to find their confidence within this vacuum. You can still find confidence. When I would pitch in high school, I had such a slow curveball (and a pretty slow fastball), and the other guys would hang on to the chain-link batting cage and laugh at me. But I didn’t lack confidence. I knew I was going to beat them. I was determined to beat them. I was going to show them. But in my core I still needed to find that sense of self-worth — which helps to explain the hopeless-romantic part. When you don’t believe deeply in yourself it’s extra hard to fall in love. I mean, love can get pretty neurotic pretty quickly if people are really uncentered.

So as I went through life I kept wrestling with this self-worth issue. Who was I, and was I someone my father would be proud of? It’s funny how that question kind of wanders in throughout the book. But it’s always there. When I opened the brewpub, and actually had a lot of employees, that was a big step. But even just in grad school, as a geologist, living with this guy Tom Metcalf who I admired, and who was so admired within our university world of geology…it just shows how fragile I was back then, and what a big step I could take when certain people helped me see I had merits.

Readers of The Opposite of Woe then watch this child of the 60s continue developing throughout the 70s, 80s, 90s, and the 21st century. We see you come into your own as a civic-minded entrepreneur taking great satisfaction in creating something for your fellow Denverites which they themselves could not envision. We see you taking well-deserved pride, first as a private citizen and then as a public official, in helping to make Colorado both one of the most pro-business and one of the most pro-environment states. If entrepreneurs need to act as “first-movers” on a given topic (pushing us beyond any complacent status quo), and if pragmatic leaders need to keep us “centered” in our approach to such developments (promoting cooperative, sustainable stewardship of our natural and cultural resources), could you offer a couple of the most pressing concerns (either at a state or national level) on which we need right now for somebody to provide both entrepreneurial vision and pragmatic centeredness?

Well first, I learned in the restaurant business that there’s no reason to have enemies. I learned that on a successful team everyone is equal, everybody matters. On a busy Friday night you learn that very quickly. But I also grew into being a leader for a group of people, and helping that group to develop a common vision of success. That took me a while. So let’s go back to the stuff I learned quickly [Laughter]. I learned that if I got into a bad mood, if I got cranky, then within a few hours the bartenders, the line cooks — everyone started acting a little cranky. It’s like catching and then spreading a cold. So before I talked to staff each day, I would look at my reflection in the vestibule (we had a window there, and you could see a bit your own reflection), and I put a smile on my face. And I actually said “It’s showtime!” like in that Bob Fosse movie [Laughter].

Then with time I realized how crucial it was in my job was to create a sense of aspiration. We didn’t just want Wynkoop to be the best brewpub in the Rockies. We wanted to be the best brewpub in America. And we wanted to create what people in the business community call “cumulative attraction” — with shoe stores, for example, all at the same corner of the shopping mall. Potential customers come to buy one pair of shoes, but then they also end up buying another. So we had shepherd’s pie, porterhouse steaks, but we also wanted to offer the city’s best vegetarian dishes. We wanted to have the most single-malt scotches (which we did, in all of Colorado). Each one of those details came out of this broader aspiration to have the best service (not just the best vegetarian meals, not just the best desserts, not just the best beer, not just the most beautiful and most historic building in the whole of Denver).

In a funny way, we still work, now at the state level, to create that same kind of aspirational entrepreneurship. And in terms of the greatest issues facing America right now, we certainly saw in the 2016 election how many millions of Americans feel left behind. A lot of people don’t realize but, consistently for the past 30 years, 70% of our kids have not ended up finishing a four-year college degree. That’s astounding. And at the same time, we’ve gotten rid of our apprenticeship programs. We’ve gotten rid of all that support we used to provide kids in high school: vocational training, practical knowledge in how to rebuild an automobile engine. My brother was an automobile mechanic, so as a 20-year-old I learned how to rebuild my Chevy 283 small V8. So I got some of that, and really can appreciate skills training as opposed to just academic or citizen-oriented training. And with all these new jobs, careers, and professions emerging, we’re definitely going to need many new types of technicians and people who can actually operate the robots and manage the automation. We’re going to have a ton of jobs that require entirely new sets of skills.

So Colorado now is piloting kind of the national model for apprenticeship programs — and not just for electricians and plumbers (which we still need), but also for a 17-year-old to spend some time outside of his or her high school, getting hands-on experience at a bank, an insurance company, an aerospace company, in advanced manufacturing. They work two days a week and get paid, and the other three days they go to a community college and study subjects that will make them even more successful at their chosen trade or profession. Then the next year, they work three days a week, and study two days. And then the last year they work four days and take classes one day. At the end of those three years, with most of these high-school-aged students still living at home, they’ve got 10 or 15 thousand dollars saved in the bank. And we count that community-college work towards college credits if at any time as adults they decide to go for a degree. They’ll already have made a year of progress towards those goals. And they’ll already have a real appreciation for what a full-time job is. And they’ll already have in-depth experience in whatever field they’ve chosen.

Soon we’ll take this program to scale. Seven years from now, we’ll have up to 20 thousand kids doing these kinds of apprenticeships. But that’s just the start. On top of that, we’ve partnered with LinkedIn, Microsoft, and the Markle Foundation. Last summer, Microsoft gave us a 26-million-dollar grant, the largest grant they’ve ever given, to create a program called Skillful.com — a tech platform that enhances the skills and talents of kids of all ages. We have to get away from this idea that you go to school until you’re 22 or 24, and then just work the rest of your life. The economy just now emerging will keep evolving much more rapidly. People will need to, and will want to, keep maintaining and creating and expanding the skill-sets they acquire throughout their life. And at any time, Skillful.com also will encourage them to click on a different profession and see which of their skills apply, which relevant skills they don’t yet have, and (most importantly) where they can get those skills, and how much this will cost. The goal we have to reach (and we already have the right technology for it) is to help our communities get out ahead of those jobs which will be lost. Right now, if you lose your job, you apply for unemployment, and they might send you to a couple classes on how to write a business plan, or how to write your resume. But we have to reach the point where, a year or two years before somebody will lose their job, they’ve already started exploring new possibilities, and already have had opportunities to learn new skills that will prepare them for the next job.

Here could we continue to unpack how your own particular entrepreneurial background might help you to think through genuinely effective economic interventions, and then to really follow through on them (and not just on the rhetorical level)? I consider one of your most distinctive political characteristics (especially within the Democratic Party — though also now within a Republican Party dominated by Donald Trump’s zero-sum thinking) your vision of the public sector not as a primary job creator, so much as a thoughtful and supportive partner for responsible business growth. So could we take the small-business skills and values cultivated over your book’s first half (emphasizing, for example: harnessing talent, facilitating a collaborative common-sense approach, tracking and eliminating needlessly stifling or wasteful or unsuccessful conditions, committing to truly serving one’s customers / constituents even while serving broader collective interests, prioritizing positive-sum civic-minded engagements over endless competition with one’s rivals), and talk about what it has meant for you to bring these specific attributes to government? Why should progressives, Democrats (and also of course moderates, Republicans, conservatives) find their own personal values and policy preferences further fortified by incorporating your vision of government seeking primarily to encourage and to engage (rather than driving, or overregulating, or simply giving laissez-faire free rein to) small-business-driven economic dynamism?

First, you’re right that we do need rules and regulations. I don’t see how anyone could fail to realize that capitalism running amok is a catastrophe for all of us. But that being said, I think most people (not everyone, but most people) would agree that individuals should gain certain benefits for their own achievements, should be rewarded for those achievements. And I think that, again within the appropriate framework of rules and regulations, most good jobs come from small-business creation. And quality of life starts with a good job. So as mayor and as governor, I consistently have said: “Hey, we Democrats are the ones who believe in government, and that doesn’t always mean that government should just keep getting bigger.” In fact, if you bring a thoughtful and efficient and frugal entrepreneurial approach to government, you can help more people for the same amount of money, and you can help them in more significant ways.

All four of my grandparents were Republicans, and all my aunts and uncles were Republicans. But my mom was widowed twice before she turned 40. She believed in a smaller government, but she still believed in government. She actually raised four Democrats. She raised us into adults with respectful appreciation for a government that runs properly. This doesn’t mean that we as Democrats should support every red-tape bureaucracy. We don’t, right? We work to make government more efficient, more successful at helping those people left behind to get back on their feet.

The Opposite of Woe also mentions you bringing a formula, a culture, and an ethos from your small-business career to your work in government. Could you describe how each of those formula / culture / ethos aspects has played out in your efforts first as mayor and then as governor to bring together business, research, artistic, and nonprofit sectors — to everybody’s mutual benefit? Again, how do you see your own “centeredness” as a leader reflected in this type of Denver- or Colorado-based creative class you’ve helped to cultivate under the sign of “hipster innovators”? What broader vision or what intuitive hunch led you to think, for example, that bringing the Clifford Styll permanent collection to Denver, and the Pedal the Plains initiative to the greater region, would somehow help to anchor whole companies and industries here?

When we make those types of investments in our communities, we see young people investing back in our communities. When we create a thousand miles of bike trails, when Denver opens more live-music venues than Austin or even Nashville has, that affects everyone, and that really helps to attract young entrepreneurs. Too many capital investments by elected officials build on what older people think of as a good idea. So we’ve also looked at what younger people value. We see the importance of culture, art, music, and all those nonprofits I’ve served on (over 40 nonprofit boards and committees while running the brewpub). Those experiences helped me make this bridge to public service, and I truly believe that when government becomes the convener, then nonprofits can become our laboratory. They can provide the resources, the social capital, the initiative to try new approaches. And when they can cultivate an initiative that works really well, then government should try to scale it and to implement it as efficiently and successfully as possible.

We continually need to find new ways to support so many vital parts of our culture. We absolutely need excellent schools. We absolutely need for our whole community to feel safe and respected. We expanded Medicaid. We got five years of more than five million dollars per-year funding from the Susan Buffett Foundation, so that we could provide long-acting reversible contraception to any young woman, regardless of their financial situation. We provided implants and all varieties of reversible contraception. We reduced teenage pregnancy by 64%. And just for the record: we always said that, as a teenager, you shouldn’t be having sex, but don’t compound one mistake with another. So roughly five thousand of our young women will have their families when they choose to, which we know will create much better outcomes. Again this all came out of the idea of getting the nonprofit support, creating a formula (both through state clinics and a whole network of NGOs), and then having the spirit, the ethos, to implement this broader vision the best we can.

But also, as you said, the important cultural parts of a city often get overlooked. So again we’ve worked extra hard on that.

Yeah, and in case the term “hipster” sounds off-putting or exclusionary to some readers, could you describe the importance to this overall dynamism of always broadening the base of potential hipster-innovators, say by developing the Denver Scholarship Foundation, so that all students in the area feel incentivized to push themselves?

Right: perhaps “hipster innovator” isn’t exactly the phrase I mean. Terms are always hard, but the West has a historic and symbolic role in the American identity. It’s the place you come to re-create yourself, or to finish your self-creation — where anyone can decide on their own dreams, and can achieve those dreams if they work hard enough. I think for projects like the Denver Scholarship Foundation, Tim and Bernie Marquez share with me this notion that if we get every kid in public elementary school (even elementary schools in the lowest-income neighborhoods) to really believe, to focus on the fact that they can go to college (even sometimes as the first person in their family to go to college), then that vision also can make each classroom more orderly, because kids will pay a little more attention, because they can see this class as relevant to them, because they believe that they have a future. And if we can make the classrooms just 15% more orderly, and our teachers can then become just 15% more effective, and we then suddenly scale this throughout all the schools (again while helping all these kids go to college), that can point our whole community in a noble and important philanthropic direction.

You mentioned the West, and your book describes an approach to “collaborative regionalism” that seems quite grounded in Colorado life — starting perhaps from your own early experiences confronting challenges in the Rocky Mountain wilderness, but gradually expanding to your sense of the American West as, at its best, a site of ongoing real-world collaboration (not just of historical conquest, or of mythologized rugged individualism). Could you trace your developing appreciation for and engagement in collaborative regionalism, say from the positive-sum collective endeavor of revitalizing LoDo in downtown Denver, to later implementing the Fast Tracks Initiative with the support of every surrounding suburban community? And which aspects of this collaborative-regionalism formula / culture / ethos could you see also working well in other regions of America, or the country as a whole?

So much of progress, whether in business or government, comes from this alignment of self-interest. So when Coloradans can recognize their own self-interest overlapping with other people’s in their community, that opens up a much broader array of possibilities for everyone. That helps us all to see all these different ways that we could and should make our situation better.

And I think we do have to always keep reminding ourselves of what has happened in the West as a place of conquest, and all the cruelty inflicted on Native Americans. I think I’m one of the only governors so far who has given a public apology — here for the atrocity and sacrilege of the Sand Creek Massacre. We have to keep looking at that history just like we have to keep looking at our history with slavery, and keep talking through and working through these original sins of ours.

But the West also has been that place where you do re-create yourself, in large part through collaborative efforts. People talk about the rugged individualist, the lone trapper up in the mountains. But the trappers never went up into the mountains alone! They went in groups of 15 or 20 people, and one person cooked, while one person laid the traps, while another skinned the pelts. Everybody had to play their active role, just as with the wagon trains. People talk about the shootouts at the O.K. Corral. But as I say in this book: the West had a lot more barn-raisings than shootouts on Main Streets.

And today you see that same collaborative effort. Again, some of us might emphasize divisive conflict when we talk about the politics of the present. But look at Denver in the last few decades. When I came in as mayor in 2003, I said from the start: “We’re going to reach out to the suburbs, because we recognize that if we don’t have great suburbs we’ll never be a great city. We’re going to do everything we can to make our suburbs the most successful, most desirable suburbs in America.”

Denver has senior water rights in relation to the suburbs. In Denver, we can use as much water as we want, whenever we want. That’s what we used to say. But the mayor appoints five board members for Denver Water, and we deliberately brought in conservation-minded board members, who would figure out how to save water for our suburbs. People told me that if I took this type of regional approach, I’d get obliterated in my reelection bid, right? They said I had to stand up for Denver, ignoring a hundred years of our collaborative history. I got re-elected with 87% of the vote. I’m the first Denver mayor in 140 years to be elected governor. Denver only makes up 20% of our metropolitan area, but Denver residents felt a genuine hunger to be part of something bigger, to be a part of this greater metro area, to be a part of this state, and to accept some responsibility for that. I think in many cases the politics of division and conflict might win you an election or two, but you end up missing so many opportunities — so what’s the point?

On the state level, I appreciate your critique of political attack ads as diminishing the “whole product category of democracy,” as demeaning an entire range of critical public conversations. I appreciate your conception of vigorous debate as our ally, but persistent partisanship as not, of incisive skepticism as our ally, but corrosive cynicism as not. And more broadly, I find impressive Colorado’s ability over the last decade to remain a political swing state without devolving into some of the ugly extremes of partisan polarity we’ve seen play out in other contested states, such as North Carolina and Wisconsin. Political theorists like Frances Lee make it clear that a balanced, broadly diversified political electorate certainly does not make inevitable the emergence of a moderate, pragmatic, outcomes-oriented political culture. So what other forces have helped most to make that possible in recent Colorado history (for an additional constraint, you can’t just say: we have the best voters)?

Again I’d emphasize the alignment of self-interest. And I’ve spent a fair amount of time with North Carolina’s new governor Roy Cooper, and I think we’re going to see a lot of change in North Carolina, because Roy has that same instinct towards unity, towards the power of unity — united we stand and divided we fall, E pluribus unum. Our founding fathers understood that being together is much more important than being right. In Colorado, we have one-third Republicans, one-third Democrats, one-third independents. And as you said, we can find collaborative unity and vision, even with a split like that.

Once or twice a year I try to interview kids who want to go to my alma mater, Wesleyan. I recently met one young woman from Fort Collins, just about to become class president. But she decided that this wouldn’t do enough for her school and its future. She has played on the same lacrosse team for eight years, and she told me she has learned through sports the importance of unity. So she switched from becoming class president to becoming a member of what they call the Enterprise Club. She took on this seemingly less powerful, less admired position — to try to determine how to get the whole student body really working together. She told me: “Unity is power in itself.”

I recently talked with Ben Rhodes about Barack Obama’s emphasis on narrative, and how if you ever hope to build unity, you first need to develop (and then you need your administration to keep living out, through concrete policy implementation) the right narrative. And here specifically for Colorado: what does it mean to you to consider Colorado a “healthy” state? What seems most distinctive about lifestyles in Colorado? What can other states borrow from these Colorado lifestyles? Why might you find it valuable for other states to cultivate their own particular lifestyles? And how again can the hard-won fusion of formula, culture, ethos among a wide array of private and public contributors keep this pursuit from becoming just some empty marketing campaign?

I’ve been thinking about this ever since we started opening brewpubs across the country. In 1997, we started looking for abandoned warehouse districts in downtowns all over the United States. We wanted each pub to have its own name, its own locally based identity. Because in Colorado we had tapped, as you’ve described, this love of place. People take great pride in living here, and I’ve always hoped for our efficient and effective style of government to become a part of their pride. Again in Colorado we’ve tried in every possible way we can think of to get people to come together and work together and build a future for themselves. And in a funny way, these brewpubs we developed also became places where people can come together, can congregate, and see a new future for their community.

I think this love of place is inherent almost everywhere in America. I’ve walked through probably hundreds of downtowns, both smaller towns and much bigger cities, and you look at the libraries, you look at the parks — you sense that at one point people really believed in these communities, even if we’ve lost that a bit. Even if these communities have faced some hard times economically, you’ll sense a renaissance just waiting to happen. I remember going to places like Shreveport (Louisiana), or Bloomington (Indiana), or Charleston (South Carolina). We opened a brewpub in Rapid City (South Dakota) that’s still there. I went three weeks ago. And the people in those communities still love their communities. Maybe some downtowns lost their focus for a time. Maybe many people have migrated away. But you also see people starting to come back. And I think for the healthy lifestyle you described, that’s the great point of departure. I mean, it’s too hot to go jogging every afternoon in Shreveport, right? But you wake up early in the morning and its beautiful! It’s maybe 75 degrees at 6:30 AM, and the city looks just beautiful in that light. It makes you want to take a walk, or go for a jog, or stop by a park. So you can recreate this anywhere. Our society keeps spending billions of dollars trying to focus our children’s attention on their hand-held computers, their cellphones, when our kids used to be out playing baseball, or kick-the-can, or exploring the woods down at the end of the block.

So in terms of a healthy lifestyle, I do think our next big renaissance will come from whole communities, both kids and adults, getting more active again. Three years ago we came up with our “Colorado the Beautiful” goal to have, within a generation, every Colorado kid within a 10-minute walk to a green space. We promise not to force them to go out and walk to that green space every single day [Laughter], but once we make that connection possible, then we can begin thinking through how to create the enticing opportunities, the attractions to really bring people out and reshape the culture — and keep strengthening our communities all along the way.

My grandfather used to tell us that love is a muscle. Real love is a muscle that you have to keep working on. Just like you need to take walks, lift weights, or do physical work to keep muscle tone, you have to actively engage love to keep it strong. Similarly, I think our communities always need to find new ways to engage in teamwork, to work together on important issues. That becomes part of the muscle that allows you to make those communal investments in light-rail, those communal investments in a park and trail system. That all comes out of working together, on an ongoing basis. So as Denver’s mayor, as Colorado’s governor, I’ve worked as hard as I can to always find new possibilities for people to work together. That’s just good muscle tone.