When you visit Oxford and walk through its cobbled lanes, beside the walls and cloisters of the colleges, you will eventually spill out to the broad thoroughfare of Saint Giles. There you will find a pub called the Eagle and Child, nicknamed the Bird and Baby, a site that has become a pilgrimage for readers and writers alike since C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien began meeting there with their circle, the Inklings, in the 1930s.

When I visited, it was easy to imagine those men, literary giants, huddled over pints in the dark-paneled alcoves. Rather than order a pint myself, I fled to the street, where to my surprise and consternation, I burst into tears. As I drifted down Saint Giles, I realized I had been overcome not by an encounter with some spirit of the Inklings, but by a potent desire: to meet there with my own writers’ group — a long-standing weekly get-together with two or three other writers, American, female — in the corners where those men had met before us, talking, reading, and making worlds. And not only making worlds, but also searching for and digging into the old wells of faith.

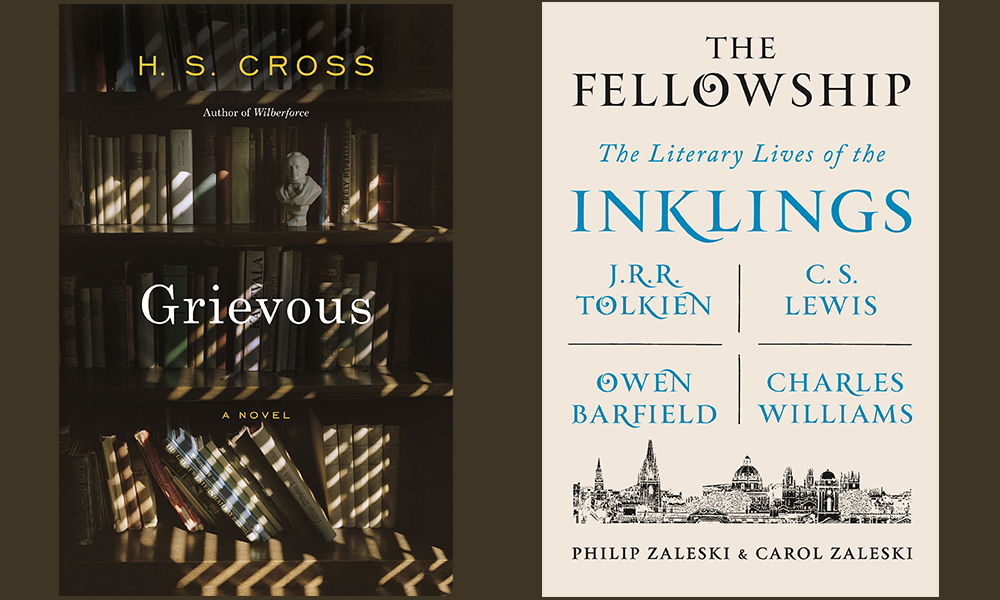

As I was finishing my second novel, Grievous (FSG, April 2019), set in an English boarding school in 1931, the same kind of atmosphere the Inklings knew, I grappled with what it meant to be writing literature in 2019 while feeling a kinship with Lewis, Tolkien, and their project. I turned to Philip and Carol Zaleski, authors of The Fellowship: the Literary Lives of the Inklings (FSG, 2015) to discuss the influence of the Inklings on literature and also the project for literary writers of faith today.

¤

H. S. CROSS: What spurred you to write The Fellowship? Were you inspired by Paul Elie’s The Life You Save May Be Your Own? These two books together present a portrait of what might be called the twentieth century Anglo-American Christian revival in literature.

PHILIP ZALESKI: Carol and I had the idea of writing about the Inklings long before we signed up to do The Fellowship with Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. We felt it would be a way to express our gratitude to J.R.R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, and their circle — and to present to the world, as best we could, the extraordinary contributions that this circle of writers has made to modern literature, to literary scholarship, and to contemporary Christian thought. Paul Elie’s wonderful book, The Life You Save May Be Your Own: An American Pilgrimage — focusing on Thomas Merton, Dorothy Day, Flannery O’Connor, and Walker Percy — gave us a model for how one might interweave four lives and shape a deeply unified story. Happily for us, Paul was our first editor at FSG before he left to join the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at Georgetown; Alex Star, our second editor, was equally skilled at shepherding us and the project.

The Inklings seemed to have a recovery or reclamation project, one that, through their influence, is still ongoing. How would you put it? Fantasy and speculative literature have become wildly popular in the 90-or-so years since Lewis and Tolkien first met, yet despite this and despite the vital intellectual influence Lewis has been on Christianity, it would seem our culture is even more in need of re-enchantment now, if by re-enchantment we mean to be brought to a place where the greatest truths and the divine story can be encountered and felt, by direct or indirect means. How do you think the re-enchantment project is going today?

PHILIP ZALESKI: “Enchantment,” despite its cloying overtones when applied to lesser work, is still the best word to describe the effect of Lewis and Tolkien’s complex and profound work upon their readership — Carol and I both fell under their literary spell early in life — and “re-enchantment” captures well the aim of the Inklings as a whole: to help the world escape from sterile materialism and rediscover the transcendent beauty and truth offered by traditional religious thought and literature, expressed by writers from Plato to T. S. Eliot.

CAROL ZALESKI: “Recovery” is an apt word for the Inklings as well. Lewis was a scholar of medieval and Renaissance literature, covering this whole span of western Christian literature, both Latin and vernacular; and he vigorously defended this legacy against modernist prejudices that would cut us off not only from the past but from spiritual currents that could revitalize our present culture. Tolkien was a medievalist as well — he revolutionized Beowulf studies and is almost certainly the reason why we have so many ardent scholars of Old English and related languages and literatures in the academy today. Moreover, his vast corpus of imaginative literature (his “mythology for England”) is fed by medieval visions of the cosmos and built upon intricate structures of medieval English (Germanic) philology. Some critics see Tolkien and Lewis as indulging in a particularly reactionary escapism (Edmund Wilson called The Lord of the Rings “juvenile trash”) but they are simply — and we think culpably — wrong.

It’s ironic, isn’t it, that we speak of the Renaissance recovery of classical antiquity as a rebirth and a reawakening, while the Victorian and modern recovery of medieval modes of thought is dismissed as a throwback, a nostalgic reaction.

PHILIP ZALESKI: Lewis and Tolkien were reclaiming not only vitally important ideas that organize and shape a culture, but also certain practical approaches to literature and the arts. It can be argued, for example, that they reclaimed storytelling from the intense emphasis upon literary style that characterized the Bloomsbury authors (Virginia Woolf, E. M. Forster, et al.) and restored to it the importance of narrative, of sheer delight in a tale.

I’m curious about your take on why Lewis and Tolkien could not appreciate Eliot’s poetry, even the Ariel poems or Four Quartets. I understand their antipathy to modernist poetry, but how could readers such as the two of them fail to feel the power of “Journey of the Magi” or “Little Gidding”? How could Lewis, who had been through the fire that produced A Grief Observed, not have confronted “East Coker”? I ask this in part because when I was widowed at 39, Four Quartets and A Grief Observed were almost the only works that I could tolerate.

CAROL ZALESKI: We’ve heard from many people that A Grief Observed was one of the few books they could read in bereavement; it’s one of Lewis’s great gifts to modern readers. And we share your admiration for Eliot, as did more than a few of the Inklings (Charles Williams and Lord David Cecil come to mind). But for Lewis and Tolkien, Eliot embodied the modernist effort to break from the past. All of these authors were responding to the horrors of world war, and while the modernists opted for rupture, the Inklings were devoted to recovery, to a living continuity with the poetry, symbolism, and faith of the past. Still, we can’t help thinking that if Lewis and Tolkien had met Eliot under different circumstances — the Eliot of Four Quartets, not of “Prufrock” — they would have realized that they were comrades in arms, on the same quest for an antidote to the modern wasteland.

Today, it seems to me, we are more fragmented than ever; not only do we lack a shared culture, we now lack a shared experience. Have we swung so far into individualism — where each person’s identity is hyper-defined, intersected, claimed, sometimes to the point that others are forbidden even to speak of it — that we cannot agree upon shared experience? It seems to me that a concern of both the Inklings and their nemesis, the Modernists, is what happens to culture when the bonds that used to hold us together are gone. Can we even have a culture? Why are we still asking this question almost a hundred years later?

Crawling back from the edge of alarmism, though, it’s clear that faith — the great faith traditions — is something shared, with people in our own time and other times. Speaking for myself, being a practicing Christian means standing with my feet not so much in the present as in the river running through the ages. “As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be.” When you say and hear that enough, you start to feel that water flowing around your ankles, and the concerns of the present look a little different, perhaps, than they looked before wading into that river. I get the impression from your book that the Inklings, in their traditionalist bent and their hearkening back to other times, were looking for treasure there not so much to explain their own cultural and societal crises as much as to unlock the cultural and societal crisis of the entire human story. How do you think an active faith practice affects the reading and writing of literature?

PHILIP ZALESKI: The Inklings and the Modernists (at least, if we take T. S. Eliot as our ideal Modernist) saw what a quick glance at any newspaper would reveal — that our society is in crisis, that recovery of a living faith is desperately needed, and that all aspects of culture, including the arts that may seem to some like merely decorative, optional pursuits, have a role to play in the recovery — or further degradation — of the human spirit. The influence of the Inklings’ example needn’t be limited to Christians. All the world’s great religions have spawned great literature, and it seems to me that it is incumbent upon Muslims, Jews, Christians, Buddhists, Hindus, and so on, to recover the riches of their own traditions and transmute them into modern classics. The great danger, I believe, is to settle for ersatz or cafeteria spirituality. Traditional religions have had centuries or millennia to deepen and refine their gold (Lewis, who recognized this, had considerable admiration for the liturgical and artistic beauty of Greek and Roman paganism, even though he was hardly a devotee of pagan belief); whereas the latest spiritual fad or a subjective practice of cafeteria religion is very unlikely to give birth to great literature. Would you agree with this?

I would, and I believe such a view puts us in the counter-culture. A difficulty I see for some of my peers (in the arts and the culture generally) is that they seem cut adrift from the great religious traditions, especially from their own. It’s not uncommon for me to encounter someone incredibly well-read in literature, history, psychology, and politics who nevertheless maintains a studied ignorance about the tenets of faith that they were raised to view as antique or even harmful. Nevertheless, people have a hunger for the real deal, for incisive, deep, surprising truth. Generic spirituality can seem fresh and unladen with baggage, but it doesn’t have the roots to grapple with the biggest questions. One of the tasks of literature today, it seems to me, is to reintroduce people to the deep wells available to them, to make them aware of their hunger, and to bring the great faith traditions, disposed of by much of the twentieth century, back inside the boundaries of serious cultural discussion.

PHILIP ZALESKI: Our experience is as writers of non-fiction on religious themes — in addition to The Fellowship, Carol and I co-authored Prayer: A History, The Book of Heaven, and a forthcoming anthology on hell; and we each have our own books and essays on faith and culture. But you are a novelist — you’ve given us the critically acclaimed Wilberforce and Grievous, your forthcoming novel, both set in the boarding-school crucible that is St. Stephen’s Academy. What inspired you to create this literary world? And how do you approach your own fiction writing as a person of faith?

St. Stephen’s grew up over time, inspired by fictional boarding schools I encountered as a teenager, first the school in Stalky & Co., which is supposedly a portrait of the United Service College that Kipling attended, then the Victorian schools in Tom Brown’s Schooldays, Vice Versa, Eric or Little by Little, and others. In a way I couldn’t understand, I wanted to be inside these worlds. I was drawn to their strictness, their physicality and fortitude, their confident valuing of tradition. St. Stephen’s shares these traits as well as the general atmosphere of Anglican worship. The adults at St. Stephen’s, like the headmasters in Tom Brown and Stalky, are clear about what they believe and why they believe it — at least compared with adults as we usually see them portrayed — and they are prepared to make their case. For all its rigors, St. Stephen’s feels to me simpler and in many ways more merciful than the tangled angstiness of present-day schools, and I find its restraints both comforting and freeing.

One thing the Bible has taught me as a writer is how much energy can be stored in what’s unsaid. Those gaps are where the reader can enter into the story and encounter it directly. Just as the liturgy works on you without your effort, so I think stories and worlds work on readers. There is no fantasy in Grievous or Wilberforce (except in the books they read and imagine), but if an encounter with the past can serve as an engine for enchantment, then I suppose St. Stephen’s is part of the re-enchantment project.

CAROL ZALESKI: In his Experiment in Criticism, Lewis suggested that great literature as a whole — not just fantasy literature — has the power to re-enchant, and in so doing to refresh and recover our senses. As Lewis put it, we read because “we seek an enlargement of our being … We want to see with other eyes, to imagine with other imaginations, to feel with other hearts, as well as with our own.” The hope is that when we return to the ordinary world, we will retain something of this enlargement of our being, some of this capacity to see the world through other eyes. And this is a spiritual gift, an aspect, at least, of a life-giving and culture-shaping faith.

So true! I’m sometimes asked for my opinion about certain things that go on in my novels, particularly the grittier side of school life, but I’m less interested in what our day has to say about them than in what their perspective says about us.

I’m reminded of something a former rector of mine used to say about Christmas Eve sermons: Don’t try to be original. Just deliver the goods and sit down. Just as many preachers fail the basic task of delivering the Goods — the treasure handed down to us from the past, still active and alive in the present — so do many artists. Fiction is and must be different from homiletics, but I think we thirst for literature that delivers the Goods. We shouldn’t settle for anything less.