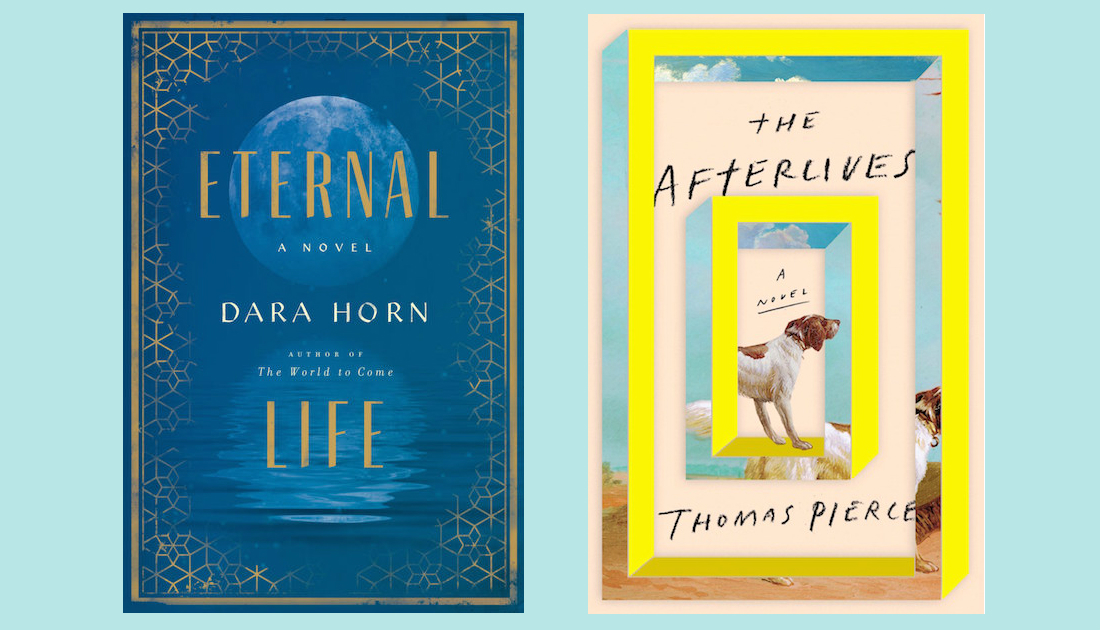

Dara Horn, author of Eternal Life from W.W. Norton, and Thomas Pierce, author of The Afterlives from Riverhead, have both written about immortality in their new novels but have taken slightly different approaches to the subject. In the interview below, we tackle what it means to live forever and why it’s not necessarily the best option.

¤

What does the concept of immortality mean to you?

DARA HORN: I think many writers are driven to write by a secret desire to stop time. Since I was a child I’ve been troubled by the idea that days disappear, and writing, for me, was an attempt to preserve those moments that I otherwise saw vanishing. As an adult I’ve come to appreciate how much of that same desire is intertwined with our obligations to others, with the civilizational project of passing on the meaning of our experiences to people who will outlive us. For parents, and plenty of non-parents too, that project isn’t abstract: it’s what you’re doing every single day while you think you’re just making someone else’s lunch. Living forever as an individual seems rather pointless to me, while that intergenerational chain of sharing what it means to be human means more and more.

THOMAS PIERCE: Well, the concept of immortality is bound up with time, and time is problematic. Physicists struggle to make sense of it. Is it smooth? Does it flow in both directions, backward and forward? Is it necessary outside of thermodynamics? Quite possibly (and this is what I tend to believe) past, present, and future are all occurring at once — as a single expression — but our conscious experience of the universe is that we are living our lives as a series of events, one after the next. But if all events are coexistent, there is no true start-point or end-point. All is. So maybe, sort of, we are immortal?

How does the past inform your characters’ present lives as well as their futures?

DARA HORN: My main character, Rachel, is a woman who can’t die — and while immortal characters are hardly original in literature, very few of them are fertile women. Rachel’s 2000 year existence turns on a choice she made in an ancient Temple in Jerusalem, but her daily life is bound up with the future of her hundreds of children, all of whom she will outlive. She’s tired of loss and frankly wants out, though things change for her as the story progresses.

THOMAS PIERCE: Many of the characters in my book are beginning what you might call second chapters. My narrator Jim has died for a few minutes, returned with no memory of any lights or angels or tunnels, and is looking for new way to think about the universe and his place in it. Annie has lost her husband and is now a single mother, back her in old hometown. They both have these traumatic events in their recent histories that haunt them in different ways, and now they are hoping to build a new life together, a new love, a new future.

Given the downside of immortality, why do you think we’re all preoccupied with finding ways to extend our lives?

DARA HORN: On the surface, it’s a love of life. But underneath that is fear. Fear of being vulnerable, fear of being powerless, fear of being forgotten or alone. Ironically, all of these things are more and more likely the longer you live. One of my grandfathers lived to 98, and while he had a loving family and even a late-life partner, he often mourned the lifelong relationships with friends whom he’d outlasted (including my grandmother, to whom he’d been married for over 50 years). Longevity enthusiasts are presumably imagining a world where EVERYONE lives forever, but that creates a much deeper problem: it would mean, at bottom, a world where nothing changes, where there’s no reason to pass anything on or rely on anyone else, a world without dynamism or adventure or the unspoken vulnerability that makes us love others in the first place.

THOMAS PIERCE: I agree with Dara that the preoccupation with life extension and immortality is probably rooted mostly in fear. Fear of impermanence and irrelevance and insignificance and smallness. When we’re afraid, we cling — to beliefs and memories and identities and groups and things and each other. I might be getting way off topic here, but it seems to me that one our biggest and most interesting challenges as humans is overcoming this fundamental fear. I think we all want to matter. And to feel useful and to belong. Maybe the way to do that isn’t to avoid death but to embrace it as an inevitability.

Both of your books touch on both the scientific pursuit of preventing aging and also the mystical beliefs about immortality. Are these two contradictory?

DARA HORN: “Preventing aging,” in scientific terms, is really about avoiding physical and mental decline rather than eliminating death, and calling it immortality may mainly be a way to get delusional billionaires to invest in it. There’s a similar bait-and-switch going on with mystical concepts of immortality. Like scientific life-extension hype that turns out to actually be about “healthspans,” religious ideas about immortality often require a person to be (wait for it) dead — and likewise, the goal of this ploy is to inspire otherwise selfish people to think beyond themselves. At bottom, though, I think religious and scientific thinking coalesces around the idea that the dead live on. Genetically, every one of us is made out of dead people. Judaism is a tradition that doesn’t place much emphasis on an afterlife, but it is a tradition where religious belief in a kind of national immortality has similarly intersected with historical fact: it’s a culture that really shouldn’t exist anymore by any historic precedent, but astoundingly is still here, thousands of years later. In the book, I took that fact and turned it into a person.

THOMAS PIERCE: There is a character in my book who considers himself to be at the vanguard of scientific research — anti-aging regimens, brain emulations, and so forth — but his faith in the power of technology to ultimately “save” him (or at least, his body/brain/mind) doesn’t strike me as all that much different than the faith of more religious folks in an everlasting soul. Like everyone else who’s ever lived on this strange little planet, we’re all doing the best we can to make sense of our existence and to infuse it with meaning. The only thing that’s really changed, I sometimes think, are the terms we use to explain that existence to ourselves. Maybe science offers the terms and explanations most appealing to you or maybe it’s religion or maybe it’s some combination of the two. Personally I have no great trouble reconciling modern science — which, really, can be pretty wild and mystical anyway — with the sense I have that the material universe is not all there is.

If you had a choice, would you choose immortality?

DARA HORN: Always leave the party while you’re still having fun.

THOMAS PIERCE: Living forever as Thomas Pierce? No, thank you. Wait — are you offering?