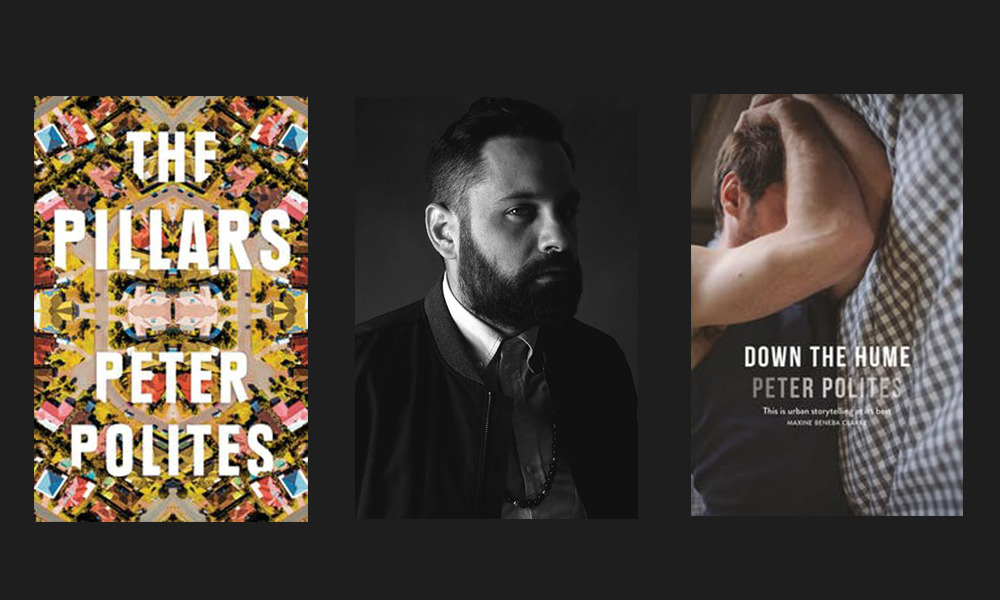

Peter Polites is a writer of Greek descent from Western Sydney. As part of the SWEATSHOP writers collective, Peter has written and performed pieces all over Australia. His first novel, Down the Hume, was shortlisted for a NSW Premier’s Literary Award in 2017. The Pillars is his second novel.

I first encountered Peter Polites through a friend at university who recommended I pick up Down the Hume during a discussion about how same-sex relationships are depicted in our popular culture. The recommendation came with a warning: Polites isn’t fucking around. After I read the first few pages of his debut, this became clear: Polites had rendered a relationship where rough sex and domestic violence bleed into each other. I was hooked. When his second novel was released, I was glad that he’d decided not to fuck around again (it had even more audacity than his first) and grateful when he agreed to let me pick his brains about his writing.

¤

JAY ANDERSON: Your work has been branded as queer-noir. You described your debut, Down the Hume, as having a green, blue, grey mise-en-scène, whereas your follow-up novel, The Pillars, in contrast, being of a sun-drenched noir. Your writing contains an Australian vernacular that has been described as nostalgic, and I love the short, clipped dialogue between your characters. Can you tell us more about your life, your work, your influences?

PETER POLITES: My mum was a Librarian Assistant and a Greek language teacher, so books have always been part of my life. (It doesn’t mean I’m better than anyone, it was actually a deficit because I lived in those fictional worlds as a distraction.) Dad was a Boilermaker, an industrial kind of metal worker, which is a mixture of science and craft. Both have old style European politics, one communist and the other fascist. Dinnertime was fun. Living in fiction as a child and then listening to political arguments while eating Greek food is just a hop away to writing novels. If you take that quarter century old theory of literary criticism that the fiction novel is a response to the nation state and its subjects, then my family environment ripened me to write.

As a child my bedtime stories were the ancient Greek myths. Hercules and his 12 labors. Odysseus was speculated to come from the island my parents came from, so my family claimed him. Also, Greeks don’t make that distinction between ancient and modern Greeks, we own our pagan nonsense as much as we do Eastern Orthodox rituals.

I have a Bachelor of Visual Arts from Sydney College of the Arts and the methodologies I learned at art school are still in my writing practice. Learning about queerness in an academic context, made me see the world in a certain way. Some readers say that I look at gay life through a queer lens, I think that’s fair. I arrived at university influenced by the theoretical and philosophical ideas of postcolonialism, post-structuralism, and all the rest of the “posts.” Brilliant journals like Third Text were doing this exciting analysis of literature, installations, and Disney films. At art school we all went down the David Lynch noir hole all the way to Gilda. I branched off into a love of the James M. Cain books. The everyday loser noir, the character whose ambitions outweigh their abilities. Although his prose lacked, I still loved the worlds and characters that he created.

After art school, I worked in different kinds of community services, refugees, youth, queer and ethnic affairs. I worked at pornographic book store, I worked for a left-wing senator. I had a bunch of mental breakdowns and then joined the emerging western Sydney writers’ group that became the Sweatshop movement and started my journey to become a writer.

My whole creative life I’ve always had a fascination for Medea. Which is why I love creating characters that have zero likeability.

That queer lens is probably why Down the Hume and The Pillars both grapple with how the politics of race, class, and sexuality intersect. For example, you undermine members of the queer community who reinforce dominant race and class discourses — the Calvin Klein-wearing, no rice/spice/chocolate on Grindr card-holding gays. Is this a conscious or subconscious process of revelations and re-evaluations for you? Perhaps, both?

I’m colloquially known as “a hot piece of ass” and critical politics (particularly sexuality, race or gender) can be formed as a resentment to a perceived exclusion from the hegemony. And I wasn’t excluded. As a regulation hottie, “Oh, I used to be gorgeous!” I say, as Moscato spills out of my stemless wine glass! I trawled through a century of peen by my mid-twenties. No seriously, I was so hot I could tell you that the sky was green, and you would agree. But my mother had no ability to be happy and I come from a political background, so these things together created a modest critical intelligence in me. I take this intelligence everywhere with me. Especially that time at a party that some fancy homo invited me too, where I would look out onto the Sydney Harbour Bridge and cast my eyes over a platter of prawns and ask why? Why these dingbats? Why did these guys win the financial lottery of a harbormaster apartment yet have the dull and listless eyes of a shop window display? And when you see that how can I not be critical of the glitter gays of Sydney?

So if the glitter gays of Sydney are featuring in your work, where else are your characters and these stories wrought from? I read that The Pillars began after you took a drive with your mother and she pointed to a house and started crying, and in another interview, you mentioned that the protagonist of Down the Hume was a version of yourself some time ago?

Mum was sitting in the passenger’s seat, she pointed to a house and started crying. She told me that when she moved to the area another Greek woman was murdered by her husband in that house. There were columns and a lemon tree out front, signifiers that a Greek family lived there. I realised that all the older women in my community knew exactly what happened in there and it stood as a warning to them. When I started thinking about that house being a monument to the patriarchal order of immigrant communities, The Pillars unfolded before me.

I write in first person, so I start with a voice of a character. For my first novel, I developed what I call a Western Sydney staccato, what some people call an accent. It’s a clipped way of speaking but heavily influenced by the second-generation diasporic youth of Western Sydney. For The Pillars, I wanted to create a voice that was slightly cheesy, slightly cynical and totally aspirational. It comes off quite pretentious which parallels that suburban myopia.

In Down the Hume the main character of Bucky is me but can only make 50 percent of the decisions that I make. The character in The Pillars is also me, hello! we share the same subject positions! Greek and gay — but because he intends to be aspirational middlebrow, he makes terrible decisions like going along with a meth orgy that fails.

I have a theory that American noirs lack because of their obsession with character and psychology. As important as character is, the forces of socialisation that bare down on the person are more important. For example, Bucky as a Greek man is unaware about the way his hirsute, swarthy body is racialized by Anglo-Australians (skips) and why he is desirable. Conversely, the character in The Pillars mistakes homewares and replica modernist furniture as a value system.

How much of these fictional world’s rests in your own then? I know you’ve pointed out previously that your mother and Pano’s, the protagonist of The Pillars, are not one in the same by any means. And I read that you make notes — of ideas, of conversations you’ve overheard — and then piece them together to write your novels. What is the process for taking these clippings of reality and turning them over in your mind until they are something else entirely?

The world that I write is Western Sydney and living here is a residency. It’s the most culturally diverse place in Australia. It’s working class cosmopolitan. It’s also economically diverse; in the car park of my apartment block you will see the latest Jeep Wranglers next to a 1991 Camry. Part of constructing narrative is this kind of sustained observation of my environment and taking notes. I try not use everyday people’s conversations, rather they inspire as a branch off point that might spark something. If I try to capture people’s talking, it’s an energy that I’m trying to transfer on the paper, not what they are saying.

I might be pouring beers at work and as different things enter my thoughts, I’ll write them down on any piece of paper I can find, receipts, or napkins. The papers live in shoebox. When I am ready, I take out the pieces of paper and then arrange satellite webs of ideas and the images that I have derived from them. The images might be the way pants get wet or seeing someone play with their hair on a CCTV monitor. Underneath the satellite webs, I’ll create a line of narrative. Once I have planned a map, I’ll take the journey of the novel.

Because I’m Greek I live by praxis. Theory and philosophy have always played an important role in both my books. To develop The Pillars, I read Jasbir Puar’s Terrorist Assemblages as a way of understanding sexuality in the state. Marriage equality really did a number on us in Australia, it was a fight for a certain kind of citizenship that underpins the colonial project in Australia. Practically I tried to insert militarized language in the sex scenes of The Pillars as a nod to this. The overarching narrative of becoming an uber gay citizen, one that can deploy their sexuality against minorities is an uncomfortable story to tell. It’s hard to think of sexual minorities as oppressive, but Mayor Pete is a cheerleader for Pax Americana. Same deal with trans people in the military. This idea of sexual minorities having freedoms can reinforce the superiority of western national identities and justify national colonial projects against First Nations people and imperial wars in the Middle East.

I can see how that philosophical underpinning has bled into your characters, like The Pillars Pano. He is a writer who reflects, as most writers do, on what this means. Especially from a financial perspective as he tries to succeed in suburbia. Ultimately, he sacrifices a perceived sense of self-dignity to ghost-write a book about a property developer for the pay off. Why did you pursue the vocation of writing in place of a more financially-stable career, or are you moonlighting as a ghost-writer for the wealthy of Sydney as well? What does one need to undertake this venture?

Between me and you, it pains me to describe myself as an artist. Cringy. But writers are artists; their medium is language. Then put the overlay of the different subject positions on me. Same sex attracted, diasporic Greek. I mean Greeks have existed for thousands of years in diaspora. And in another timeline, I could have been running a diner in Astoria or hunched over a table and pouring a braki in Moscow. My Greek diasporic identity is nothing new. Neither is my same sex attracted cis-male identity. Off the top of my head there are three different published writers in Australia that share this Greek and gay thing. Hi boys! And there’s Cavafy all the way to David Sedaris who are also Greek gay writers of the diaspora. So, in that case perhaps socialization plays more of a role than the manifest destiny of the individual. What I’m saying is that maybe the forces of socialization turn Greek diasporic gay men into writers.

In regard to your second question, about becoming a ghost-writer for a rich jerk, I think what I learned from The Pillars is that if you were to undertake this venture just leave your dignity at the door. It’s less messy.

Lots of Greek diasporic gay men perhaps, but you all have different approaches. In your fictional worlds you tackle harrowing subject matter — Down the Hume grapples with the complexity of domestic violence, as mentioned. Was there particular motivation for this, or was it simply the story the muses delivered, and what were the emotional difficulties of doing so?

Both Down the Hume and The Pillars deal with domestic violence. It’s because I grew up in a house where my mother experienced coercive control. Both novels deal with drugs, because I have a personal history of using all kinds of drugs. These things release for me when I think about writing for my community and other readers.

I use comedy a lot in my personal life and I’ve only realized that I like making people laugh because I did this as a child to ease tension in the family home. Comedy is in my books too. So, for me comedy offers a reprise from going through a drug induced psychosis or witnessing domestic violence in my family.

Once I know this stuff is going to be released, I am removed from it, the stories become bigger than my personal grievances, they become about the state, about immigration, about sexuality, about working class communities, more important than Peter Polites. Thinking about things bigger than myself is a survival strategy.

What have been some of the challenges and joys, the lows and highs, of this process of thinking about things bigger than yourself — of the writing, editing and publication process to date?

Let me tell you this. Writing folk are the best kind of folk. Well some of them. Some of the highlights from publishing books have been meeting some of the most interesting and generous people I’ve ever met in my life.

What are you currently reading, Peter, and where will your writing take you next?

Despite my hostility to the migrant trauma memoir, I loved Ocean Vuong’s contribution to this genre. He is a poet at heart and the images arrest me.

In terms of new frontiers there is something disarmingly charming about Ronnie Scott’s novel The Adversary — it’s about same sex attracted men set in bohemian Melbourne and it shows that at the heart of contemporary gay life are the same concerns of manners that the Brontë sisters or Austen teased out.

I queened out when reading Damascus by Christos Tsoilkas. It’s such a significant shift in his work. He is an author that I have been following since my teens and I’ve always loved historical fiction, so I was excited to read this. And adding homoeroticism into the stories of the saints and disciples — amazing!

I always try and read the brilliant First Nations women’s writers like Ellen Van Neervan and Melissa Lucashenko. It is a truth acknowledged by all Australian writers who matter that Alexis Wright is the most exciting and important writer living today, I don’t have the ability to talk about her fiction.

Hopefully my writing career will give me more opportunities like this. Loose, free form reflections. Also, I’d really like to write a portrait of a gentle and generous masculinity, using that all too queer lens. All these horrible characters are taking a toll.