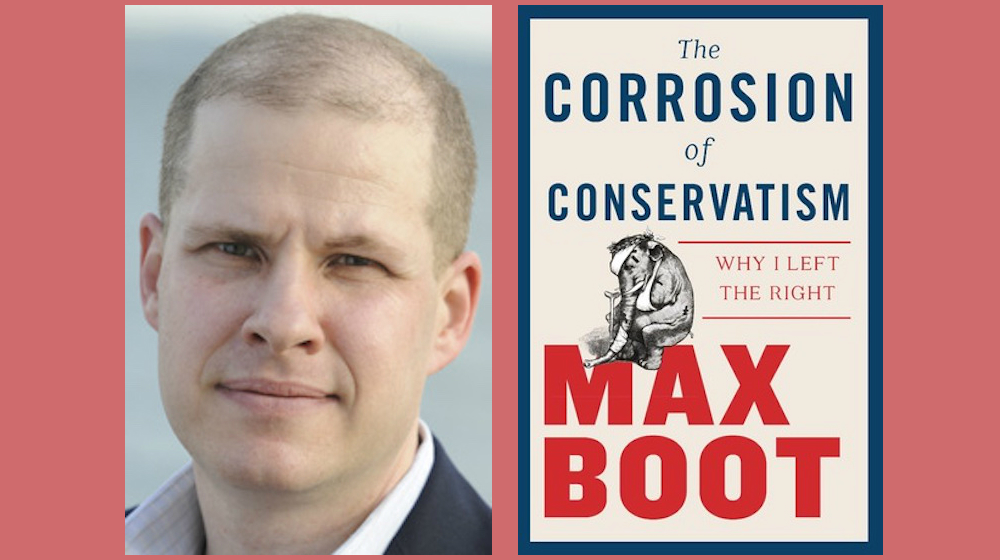

What might it take for self-respecting conservatives to wish on today’s Republican Party “devastating defeat”? What about for all those Republicans for whom Donald Trump’s racist xenophobia has not yet provided “a strong enough reason to vote against him”? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Max Boot. This present conversation focuses on Boot’s book The Corrosion of Conservatism: Why I Left the Right. An acclaimed author, historian, and foreign-policy analyst, Boot has been called one of the “world’s leading authorities on armed conflict” by the International Institute for Strategic Studies. He is a Senior Fellow in National Security Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, a columnist for the Washington Post, and a global-affairs analyst for CNN. He has served as an adviser to US commanders in Iraq and Afghanistan, and as a senior foreign-policy adviser to presidential campaigns for John McCain, Mitt Romney, and Marco Rubio. Before joining the CFR, Boot worked as a writer and editor at the Wall Street Journal and the Christian Science Monitor. More recently, he has been a columnist for Foreign Policy, a contributing editor to the Los Angeles Times, and a regular contributor to the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and USA Today.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Your book describes Donald Trump as more hostile to a distinctly American mode of optimistic, inclusive conservativism than any previous US president. But it also describes your increasing disillusionment with Republican elites abetting Trump’s ascendancy, with a Republican base voting for this singularly incompetent and intolerant candidate in the same numbers as they had voted for past nominees, and with hypocritical conservative constituencies (with roughly 75% of Christian fundamentalists still endorsing an aggressively transgressive figure like Trump, and with 61% of the “family values”-pledged Republican Party even declaring Trump a good role model for their children). So could you first sketch a couple concrete experiences which have proved especially telling in your shift from the belief that Trump’s crass populism had hijacked your principled party — to the dawning recognition that both the Republican Party and the conservative principles you enthusiastically endorsed actually had been entwined with some of American history’s and modern American democracy’s most troubling aspects for decades now?

MAX BOOT: Well I felt viscerally opposed to Trump from the moment he first came down the escalator at Trump Tower, castigating Mexicans as criminals and drug dealers. I considered that the kind of thing you simply could not do in American politics and survive. I just assumed that, before long, the Republican Party would reject Trump. And of course this attack on Mexicans soon led to Trump’s offensive and racist campaign call for a total and complete shutdown of all Muslims entering the United States. And here again I expected the Republican Party to reject Trump’s bigoted statements. I mean, I never thought Trump would win a single Republican primary. But then he started winning primary after primary, and it astonished and nauseated me to see how many Republicans who had once castigated him as bigoted, unqualified, unfit, a kook, a madman and so forth all then fell into line to endorse him.

The enormity of that shift was brought home to me in the summer of 2016, while talking with a friend who had served in the George W. Bush administration and who, I thought, opposed Trump as much as I did. We knew that Trump soon would clinch the nomination, but I said: “A, I don’t think he can possibly beat Hillary Clinton. And B, I don’t think he should beat Hillary Clinton. I’ll definitely vote against Donald Trump this fall.” And my friend said: “Oh Max, you’re so naive. You think politics is about these abstract ideas. Politics is about tribal affiliation. Donald Trump now is the leader of my tribe. Therefore, I’ll support him.”

I couldn’t believe it. But my friend actually had a better grasp on the Republican base than I did. Only over time did I come to realize that Trump’s racism and xenophobia actually gave people a reason to vote for him. And then, for too many of the remaining Republicans, Trump’s racism and xenophobia did not provide a strong enough reason to vote against him. So at that point, just looking around, it started becoming more apparent that this was not the party I had originally joined — or thought I had joined. I mean, this whole experience pushed me to recognize some very disturbing, very ugly truths that probably had been there all along, even if I had been too blinded by loyalty to the Republican Party to acknowledge them.

In terms of that loyalty you long felt, could we also start to introduce parts of your personal backstory? For progressives, let’s say, who can’t resist associating “conservative” with “criminal” (particularly in the case of a former Wall Street Journal op-ed page editor and vocal Iraq War proponent), could you outline some mitigating autobiographical circumstances that might make your youthful enthusiasms for a democracy-exporting foreign policy (a foreign policy infused with a “moral dimension”) more explicable?

Sure. I’d say the first relevant biographical fact would come from me being born in the Soviet Union, at a time when a communist dictatorship still ruled. I came with my family to Los Angeles in 1976. And like many arrivals from communist countries (whether the Soviet Union, or Cuba, or Vietnam, or what have you), I gravitated towards the more anti-communist wing of the American political spectrum — which, in the 1980s, of course meant Ronald Reagan and the Republican Party. I really thrilled to President Reagan’s rhetoric calling the Soviet Union the evil empire, demanding “Tear down this wall,” and championing dissidents like Anatoly Sharansky. From my view, Reagan really stood up for freedom and democracy. Reagan championed America as a force for good in the world, whereas many leftists I grew up around (in places like Berkeley, where I went to school) seemed to hold a romanticized view of dictators like Daniel Ortega or Fidel Castro, and refused to call them out for their offenses against their own people (to say nothing of their anti-American foreign policy). And coming from a country that had no freedom back then (and which has no freedom again now), I’ve always valued human rights, and I’ve never taken those for granted. I’ve also always thought that, despite America’s imperfections, and despite our own long-term sins (whether against Native Americans or against people in other countries), on the whole, America has been and has retained the potential to be a force for good in the world.

I still consider that the right mission, the right role for America in the world, as long as we do it prudently. And this enthusiasm for championing democracy and human rights led me to support the war in Iraq, which I now regret. In hindsight (and of course many Americans recognized this at the time), America did not act prudently with that hubristic, overambitious invasion. So again that basically idealistic impulse (that repulsion with Saddam Hussein’s tyranny, with the fact that he had gassed the Kurds, and had slaughtered the Shia, in addition to the fact that I believed along with much of the world that he was again developing weapons of mass destruction) eventually led to a chastening lesson for me on the limitations of American power, though I still believe America should try to stand (as much as pragmatically possible — and it’s not always possible) for the values embodied in our Declaration of Independence and our Constitution. So it has just shocked me to watch the Republican Party move from a president who said “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall,” to a president who says: “Mr. Putin has been very strong and convincing in his denials.”

Of course The Corrosion of Conservatism also presents you entering this country basically as a stateless person, with no resources or clear prospects. And though you received asylum as a target of Brezhnev-era Soviet anti-Semitism, you gradually became a target of intensified anti-Semitism within the US itself, first under the guise of conspiratorial claims about “neo-cons” sabotaging US national interests, and later through denunciatory rants more openly echoing 20th-century European fascism. And here I found especially interesting how these increasingly common populist departures from any pretense towards a credo-based conception of American national character have pushed even you (an individual much more drawn to intellectualized identity than most of us) towards ethnic identification as a Russian and as a Jew. So, still in terms of your own personal experience, could you describe first-hand how broader conservative complicity in this Trump presidency catalyzes precisely the types of “cultural fragmentation” that conservatives claim to abhor?

Right, as a young immigrant, I first just wanted, most of all, to assimilate. And you know, I think I did that pretty successfully, maybe overzealously, because I actually don’t even speak Russian anymore. I grew up watching football and The Dukes of Hazzard. I became pretty indistinguishable from many other Americans, despite not having been born here. And to my mind, this again shows the greatness and the genius of America: that it can take immigrants like me, immigrants from more than 100 nations, and bring them together to become Americans. Despite our lack of shared ethnicity or of a common history, we can make our own history together because we all believe in life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. I really thought that was all it took to become an American. And it certainly heightened my appreciation for America that I never encountered anti-Semitism here, at least until about 2015. I mean, maybe I’ve just lived a sheltered existence (primarily in places like LA, Berkeley, New Haven, Cambridge, and New York), but I just thought of myself as an ordinary American.

Then when Trump started running for office, a lot of ugliness started to bubble up from the sewers of American politics. I started getting these vile anti-Semitic attacks on Twitter and email. Somebody posted on Twitter an image of me in a gas chamber, with Donald Trump dressed as an SS officer pulling the lever. And this has become a pretty common experience, I think, for many Jewish pundits, and even for people who just have Jewish-sounding names. All of a sudden, the number of open anti-Semites seemed to grow exponentially. And if you look at statistics from the Anti-Defamation League, the number of anti-Semitic incidents does seem to have rocketed upwards for the last several years, with of course the most catastrophic and calamitous attack being the synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh.

I think we have to recognize that, clearly, these forces of hatred and bigotry had been there all along. But Donald Trump now has given them an excuse to come out in the open. Trump might be more openly racist and xenophobic than anti-Semitic, but he nevertheless traffics in anti-Semitic discourse — for example, by blaming George Soros for this so-called caravan of Central American immigrants that Trump pretends pose some kind of security threat to the United States, or by declaring that there were “very fine people” on both sides in Charlottesville (basically equating neo-Nazis with their critics). And every time Trump champions Confederate monuments or makes some equivalent gesture, you just see more haters and bigots come out into the open.

So yes, that whole social phenomenon and personal experience really has made me stop and realize: Oh wait a second, maybe I’m not some generic American. Maybe I’m still an immigrant. Maybe I’m still an outsider. I’m still a minority. I’m a Jew. And in some ways, Trump and especially people like Steve Bannon and Stephen Miller I think intend just that. I think they’re actively trying to redefine who gets to call themselves American.

From my perspective, we’ve always been a credo nation, a country based not on blood and soil, but on a common set of beliefs. From my perspective, we of course have done an imperfect job, but still a better job than any other nation in assimilating people from many different cultures and backgrounds. But from the nativist worldview that people like Bannon and Miller hold (and that Trump has bought into), what counts are not your beliefs but where you were born and your skin color. They basically are suggesting that only white, native-born Christians are real Americans. They basically have decided only to champion that select group of people, and to treat everybody else as some kind of threatening other who undermines everything that makes America great. To be honest, I see no greater threat to the country than this literally anti-American belief system championed by the president of the United States.

We’ve mentioned your commitment to abstract, philosophically grounded political principles, though of course this book (which frequently categorizes itself as an “intellectual journey,” but which also admits it could have been titled “Ex-Friends”) traces how even our broadest ideological commitments can get bound up with much more intimate aspects of personal and social identity. At the same time, this book makes the compelling case that conservatives’ deft establishment over the past few decades of a self-sufficient cultural infrastructure (bringing together big donors, think-tank wonks, institutional backers, and a much broader constituency of media consumers) ultimately made it almost impossible for “individual voices of conscience” to combat the increasingly insular Republican Party’s know-nothing turn — with any honest reckoning bringing public censure, professional isolation, loss of social stature and economic livelihood. Here what might any reader, of any political orientation, take from The Corrosion of Conservatism’s account of what it’s like to recognize and perhaps to resist these types of interpersonal or institutional partisan binds that can structure our civic participation far more fundamentally than the principled values we espouse and perhaps even cherish?

The big lesson I take from my own experience points to the danger of any ideology, whether left-wing or right-wing. I definitely think that confirmation bias distorts how we interpret the world, and conform to our ideologies, and dismiss inconvenient facts. And of course we also now have a massive social and economic infrastructure in place essentially to keep you from challenging your own side’s orthodoxy. I certainly discovered that for myself on the right, but of course it also exists on the left, and for any kind of movement which basically winds up policing its own members. A lot of this happens unconsciously, but also, as you say, through social and financial pressure directed at anybody seen as a troublemaker, as a deviant, as unreliable. Friendships can dry up. Funding can dry up.

And breaking from the right in relation to Trump made me realize ways in which I myself had circumscribed my own utterances over the years. I’d never said anything I didn’t believe in. But I tended to kind of stay in my own lane, focusing on foreign policy, on defense policy, even though I didn’t really agree with the Republican Party on opposing abortion, or questioning climate change, or opposing gun control. I never said much about all of that, because I just didn’t view it as my responsibility to speak out. Or even when Donald Trump started engaging in this crackpot conspiracy-mongering about President Obama’s birth certificate, I considered that a bunch of lunacy, but it still didn’t really seem like my place to speak out, as a defense and foreign-policy analyst.

Of course in hindsight I can see how many of us made similar compromises, and just didn’t say anything as the conservative movement plunged into this morass of bigotry and irrationality. In hindsight, I can recognize that all as a huge mistake, for which I and other conservatives definitely bear some blame. Even if we didn’t promote these crackpot ideas, we didn’t explicitly oppose them. And I think, in some ways, we acted cowardly. I consider it cowardly that I did not speak out, that I did not oppose some of the extremism I saw on my own side.

Again, it’s not like I wrote in favor of assault rifles or opposing action on climate change. I just didn’t address it. Partisans typically don’t want to start up a fight on their own side. You figure out a way to bond and to think: Okay, I’m no social conservative, but I need to make common ground with the social conservatives. That’s how we’ll gain power. That’s how political movements work. And again, in hindsight, I regret and feel significant guilt about those kinds of compromises I’ve made over the years. For similar reasons, you don’t see me rushing to join the Democratic Party or align myself to some other ideological movement right now. I value the flexibility I can find by staying kind of moderate or centrist or outside any focused ideological stance. I feel much more able than in the past to call things as I see them.

Sure I value the book’s grappling with partisan cultural identity especially because, as difficult as it might be to leave behind all of this particular identity’s personally nurturing and professionally rewarding aspects, partisan identity actually seems much easier to push beyond than most of our conventional identity categories, right? Partisanship doesn’t have any pseudo-biological fixity, perpetually reinforced by everyday social interactions. Partisanship doesn’t carry the historical baggage of some longstanding social dominance in which either Democrats or Republicans have accumulated generations worth of privilege / obliviousness while the other side has accumulated disadvantage / anger. So at least in your wildest dreams for this book, would you hope for it not simply to document the corrosion of conservatism, but to enact an exemplary de-escalation of partisan identity — a de-escalation in which avowed progressives don’t just respond “Yeah Max, how did you ever get fooled by such hypocritical rhetoric and idiotic policies in the first place?” but instead question their own contribution to dysfunctional partisan dialogues?

Well first I should just say that some readers have responded quite generously to the book. People like Jonathan Chait and Andrew Sullivan have had very kind things to say about it and about my role in politics. And then others, of course, have had less kind things to say. I mean some people on the American left still say that I’m a war criminal who should be banished from the political debate, or that I should get no credit whatsoever for rethinking any of my views, because everything has been completely obvious to the other side all along.

Personally, I don’t consider that type of response very helpful, but I also don’t want to absolve myself of blame. And a number of readers have noted that I in fact stay pretty self-critical throughout this book — that I actually own up to my errors, and try to grapple with them, and to find a way forward for a more moderate and centrist politics. And I would hope, like you said, that the response from the left wouldn’t involve this chest-beating triumphalism, or any kind of: “Hey, we were right all along. Why were you so stupid?”

In fact, I still see plenty on the left that doesn’t make much sense today. I mean, I’ve just been writing about how some progressive opponents of Trump have wound up de facto supporters of the Maduro dictatorship in Venezuela. I don’t think that makes a lot of sense. I certainly don’t see much that Trump has done right (almost nothing, in fact), but of course even Trump occasionally stumbles onto some policy that actually makes sense and that deserves support from our allies. And I do think that leftists need to rethink their reflexive knee-jerk ideological responses just as much as people on the right do. I don’t at all doubt that the Republican Party has taken this escalatory cycle of partisan extremism much farther than the Democratic Party has. But I also fear that same polarizing on the right now pushing some Democrats to say: “Let’s go as far to the left as possible.”

As somebody fiscally conservative, socially liberal, who believes in action on climate change, who believes in American global leadership, who believe in free trade, who believes in gun control, I just don’t see either party speaking for me. And individually, each of those policies remains quite popular, even if no political party in America can coherently synthesize and champion that broader group of beliefs. So fundamentally, at the end of the day, beyond any individual policy preferences, I really believe we need to start from the assumption that no ideological group has a monopoly on the truth, and that we can’t achieve positive results in Washington by embracing ideological orthodoxy on either the left or the right. I think the only way forward for us involves making the kinds of compromises, the gestures of reaching across the aisle, that partisans on both sides abhor.

So here again, this book’s personal conversion narrative hints at the prospect for any number of individuals to come to equivalent realizations about disturbing trends (both at present, and across US history) in conservative partisan identity, and perhaps in partisan identity as a whole. So could we start talking through in more detail what you consider the most constructive balance of non-polarizing engagement and of less comfortable consciousness-raising, to help others arrive at such a critical perspective? The Corrosion of Conservatism does acknowledge for example, and as you’ve just suggested, that certain audiences find your own recent intellectual journey “obvious and pathetic,” and insufficient for excusing past advocacy for military intervention, or past apparent indifference to marginalized groups’ claims of systemic social injustice. But from your own lived perspective, when has progressive reluctance to welcome you into the fold (as, at the very least, a responsible public voice worth hearing out) constructively pushed you to question ever further your own unacknowledged assumptions? And when have you most acutely sensed progressive tendencies to let overly personalized judgment get in the way of potentially promising political realignments?

Well I don’t know that pushing people or confronting them is necessarily all that constructive. At least in my own experience (though I think the social-science research tends to back this up), when people confront you, when people get in your face, most of us just become defensive, shut down, and get more entrenched in our own belief systems. And of course certain people would never be persuadable that way. I mean, 30% of the American population thinks Donald Trump walks on water. But other Americans do remain much more malleable, and much more open to fact and reason and to changing their mind based on empirical evidence. You saw, for example, this shift against the Republican Party between 2016 and 2018, especially among moderate suburban voters, especially women.

Similarly, on a personal level, I’ve rethought certain of my own views — not because some personal attack by progressives made me see the light, but because I kept looking at the evidence. This book discusses, for example, how Donald Trump’s election awakened me to the extent to which racism remains such a real threat in America, how I’d overstated the extent to which we’d overcome this fundamental flaw of ours. Clearly we hadn’t, and clearly all the videos showing police brutality against African Americans confirm this fact. So I can’t deny that evidence. So I have to shift my views and say: “I’ve been wrong about this. People on the left are right. Racism really is a much bigger issue than I’d realized.”

Or after everything coming out of the Me Too movement, I couldn’t help but realize: Wait a second. Feminists are right. There is so much more male oppression, with so many more men acting in horrible and ugly ways, than I ever would have imagined possible in 2019 America. But it’s obviously true. And so again that has shifted my views.

And of course seeing the fallout from the Iraq War, and seeing how disastrously that worked out, shifted my views. Again that made me realize: Oh wait a second, maybe preemptive military engagements are almost always a bad idea. So I really have tried to shift my views based on these facts, and I think everybody should try to do that. But I also don’t want to downplay how hard this is. Especially when the facts undermine your ideology, you can’t help feeling this very strong tendency (no matter what side you start from) to ignore those facts or to spin those facts in some way that reinforces your ideological predispositions — which I consider very dangerous.

And then to start getting into the practical, pragmatic politics: I think Democrats have a real opportunity right now, a once-in-a-generation opportunity, to become America’s majority party, and to inflict the kind of devastation that the Republican Party deserves for their support of this bigoted bully in the White House. But I sense that the only way Democrats can seize this opportunity is to seize the center of the political spectrum. They won’t become the majority party by pushing hard to the left. They might satisfy certain ideological impulses that way, but about 40% of the country considers itself independent. I mean, those aren’t all consistent swing voters, but a substantial number of them are. And if you compare the 2016 and 2018 election results, you can see that a major reason why Democrats did so well in 2018 didn’t come from fielding progressive firebrands like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez or Ilhan Omar. It came from fielding a lot of moderate and relatively conservative Democratic candidates well-attuned to their districts, many of which went for Trump in 2016. So again I’d stress that Democrats need to appeal to that moderate center of this country going forward, though I sense they’ll find it hard to resist staking out an adamantly progressive position basically on every topic. You can call it boring or not sexy, but I still consider centrism the only way to go for Democrats, both for pragmatic and political reasons.

Here The Corrosion of Conservatism describes well an inherent tension in how a classically liberal (free-market) society by definition seems to bring forth constant economic, technological, and corresponding social change. And here again in terms of traps that modern US conservativism seems to have set for itself, I think of an anti-New Deal coalition, premised upon resistance to robust state intervention (say in the form of sufficient social-safety nets, proactive educational and job-retraining initiatives, promotions of equitable economic prospects and environmental sustainability), as basically boxing itself into the position of responding to late-20th- and early-21st-century automation-driven dislocations by appealing to nostalgic nativist scapegoating. But in terms of how a society (how our society) could respond much more effectively to such structural displacements, could we take some of the bedrock conservative attributes that The Corrosion of Conservatism enumerates (among them: prudent and incremental policy-making based on empirical study, respect for the virtues of personal character and family and community, support for distributed economic growth and integration and immigration and assimilation), and could you describe where you might see the most room for a wide-ranging plurality of American voters to coalesce under the banner of classical or post-classical liberalism today? What could be the philosophical foundation for such a confluence of diverse constituencies, and / or a few specific issues on which a pragmatic coalition could emerge?

First, I do sense the opportunity for an awful lot of centrist solutions to some very pressing problems. Take gun control, with many gun-control measures supported by an overwhelming majority of Americans. Even most gun owners support universal background checks, for example, or limits on large-capacity magazines. What stands in the way is NRA opposition to any reasonable solution. They really have a hammer hold on the Republican Party, because they can mobilize single-issue voters, and they have a lot of money to throw around. But you have to assume that bipartisan agreement could still happen here. I mean, even Ronald Reagan supported an assault-rifle ban. And I do think many Republican voters still would commit to moderate solutions. Again I especially think you have a lot of college-educated suburban women unwilling to tolerate more school shootings.

Or consider climate change, where the fossil-fuel lobby again has a hammer lock on the Republican Party, and of course the president himself remains a climate denier. I still sense this growing realization among Republicans that we face a true climate emergency, and I sense increasing numbers of middle-of-the-road voters also understanding that.

At the same time, I sense some progressives want to use their Green New Deal proposals as an excuse to enact this overarching social agenda, with many components having nothing to do with climate change. I mean, the Green New Deal includes job guarantees, free higher education and medical care. These might all be good policies, but they obviously don’t have anything to do with climate change. So I again sense the opportunity for bipartisan agreement on something more like an escalating carbon tax (as a way to wean us off our fossil-fuel dependence), which the vast majority of economists would recommend. I think if progressives would set their sights a bit lower than the Green New Deal, and push for a carbon tax, they could find some support among people in the center of our political spectrum. And more generally I think you often could find more agreement than appears obvious on the surface, because American political activists and political leaders have their own reasons for exacerbating division.

Here with your Green New Deal critique still in mind, and perhaps to ask my previous question more directly: with your book offering a classic left-leaning account of the social-welfare state as in fact a conservative project (protecting market capitalism from perennial Marxist threat), I wondered as I often do why nobody has yet figured out the political rhetoric that could frame being pro-social-safety-net, pro-environment, pro-rule-of-law domestically and globally (which doesn’t have to mean getting “tough on crime” or rushing to military intervention), pro-immigration, pro-social-tolerance and social-mobility, all as a (or perhaps the) quintessential American conservative project.

I think President Obama tried to do some of that. President Obama was a pretty moderate figure, who in many ways modeled himself after President Eisenhower as much as anybody. And as we saw, Obama didn’t get a lot of traction this way. Again, perhaps in hindsight, Republican voters will discover the virtues of Obamacare when they see it as the only alternative to Medicare for all. And given how far the Democratic Party has moved to the left since Obama, I sense some conservatives and Republicans might rethink their hatred for Obama, and realize he was much more moderate than they had realized.

But I think we now will need more than just some new Obama-like figure. I still find staggering the number of Americans who voted both for Barack Obama and for Donald Trump. I guess this just confirms that charismatic individuals with forceful personalities can sometimes sell themselves to a wide variety of American voters. And of course one other thing President Obama did so successfully was to make himself non-threatening to so many white voters. Even though he would become the first African American president, he never campaigned in a divisive manner. He talked about bringing us all together, about making us feel proud as a country. I think we’ll need much more of that going forward if Democrats want to enact a moderate liberal agenda. I think all of the 2020 candidates must confront that basic challenge, and I can only hope that the Democrats select somebody who can deliver that message. My nightmare is that they’ll select somebody who, like Trump, specializes in energizing the base and just alienating the other side. I wouldn’t even consider that good politics, because we have to remember that Trump basically lucked into the presidency despite losing the popular vote. But even if that more far-left approach did make for good politics, I’d consider it disastrous from a policy perspective. Trump and his partisans have further divided us, and we need to be brought back together. We can’t survive as a country if we start oscillating from far right to far left.

And for just a couple compelling instances of how a classic liberal like yourself still can critique present-day Republicanism best of all, I especially appreciate your argument that any conservative enthused by Trump’s judicial appointments should be much more distressed by this president’s corrosion of American rule of law (as Trump characterizes the FBI as a “den of thieves,” openly acknowledges his efforts to politicize Justice Department initiatives, and even elicits a public reprimand from his own recent Supreme Court appointee Neil Gorsuch). Similarly, I very much appreciate your lucid account of postwar US global hegemony being secured largely by other countries not perceiving our position as an existential threat, not feeling the need to band together and form a coalition of resistance — but with Trump now engaging in a “unilateral disarmament” of this crucial soft power. If you bring those arguments to the Federalist Society or the Hoover Institution today, how do they get received? Or what will it take for such arguments to get a sustained hearing in such spaces?

The first thing to say is that I’m not very welcome in conservative institutions these days [Laughter]. I’ve alienated a lot of people on the right. I’ve gone even further than many Never Trumpers, because I don’t just question Donald Trump, but broader conservative-movement trends over the past several decades that led to Trump. And I do think conservatives need to face this very real question of what comes after Trump. Can any principled conservatism survive him? I mean, I still see a few small flickers of principled conservatism out there, with tiny media organizations like The Bulwark, and people like Charlie Sykes, or Bill Kristol, or George Will, Mike Gerson, Peter Wehner, a handful of others. Though as I joke in the book, there seem to be enough of us for a dinner party, but maybe not for a political party.

But of course an outcast movement eventually can rise up and become quite powerful. In fact, that happened with the modern conservative movement, starting off at the fringe of American politics in the 1950s, and by the 1980s reaching the White House (even though some of these conservatives still found their champion, Ronald Reagan, too ideologically impure). And it may not always seem like it, but I do sense conservative partisan identity very much in flux right now. Of course it shocks me that 80 to 90 percent of Republicans continue to support President Trump, but a number of former Republicans have left the party in disgust, and many others might now be Republican in name only.

So I do sense significant potential for a realignment to occur. A lot depends on what happens over the next couple elections. Well Trumpism get repudiated? I mean, if the Republicans suffer a devastating loss in 2020 (which I certainly hope happens), that should send a clear message, and could leave the party open to a desperately needed rethinking. And I do believe America needs a responsible center-right party. We’re all in deep trouble if the Republican Party becomes forevermore a subsidiary of Fox News. So my sincerest hope is that this current Republican Party suffers devastating defeat for its support of Trump, until Republicans finally relent from this path they’ve taken, and stumble their way back to a more centrist and reasonable posture rejecting rank appeals to bigotry and hatred.

Within that context, could we pick up The Corrosion of Conservatism’s call for some Republican leader deserving of that status to run an insurgent 2020 presidential campaign intended to weaken Trump as much as to actually pull off an upset — and for self-respecting conservatives to vote against all Republican candidates until this current nativist white-nationalist GOP gets “burned to the ground”? And what historical analogies (perhaps to 20th-century European fascism, or to past strains of ugly American populism, or to Pete Wilson’s more recent nativist politics losing California to Democrats for at least a generation) might seem most salient to which audiences as you make your case?

You know I consider it the primary imperative to try to reclaim the Republican Party from Donald Trump. And historically, if you consider the past 50 years, sitting presidents who face substantial primary challenges typically lose the general election. Now of course you could argue about cause and effect here, and say that these candidates faced challengers because they looked likely to lose anyway. But nevertheless, if you think back to Eugene McCarthy driving LBJ out of the race in 1968, or Ronald Reagan undermining Gerald Ford in 1976, or Ted Kennedy with Jimmy Carter in 1980, or Pat Buchanan with George H.W. Bush in 1992 — that’s precisely the kind of challenge that I hope President Trump will see.

Already Bill Weld has jumped into the race. I hope he can make a credible run. I consider him a very appealing, idiosyncratic figure. It seems that Larry Hogan, the governor of Maryland, has given some serious thought. Again I’d consider him a great champion of a very different kind of Republicanism. And you also see evidence that voters in places like New Hampshire could be quite open to an alternate candidate, with polls showing that maybe 30% of Republicans would like to nominate somebody else for party leadership in 2020. From my view, this makes it all the more imperative for somebody like Weld, or Hogan, or maybe John Kasich to fly the flag of a more principled, less compromised conservatism — as a first step towards reclaiming the Republican Party from Donald Trump.

And then in terms of broader vulnerabilities of American democracy that have been exposed and exacerbated in the past few years, what to make of the fact that when American conservativism still had patrician gatekeepers, it typically presented its more civil, inclusive, tolerant, constructive face to the world? Or that the eclipse of such gatekeeping, both among Democrats and Republicans, seems likely to facilitate further populist appeals (say on trade or immigration) with wide-ranging political resonance? Or that historical trends suggest Trump’s own mode of clumsy norm-breaking politics will beckon forth more administratively competent, less chaotic populist movements to follow, again potentially from any number of fronts? Within this precipitous context, what types of institutional reforms (perhaps more democratic, or less democratic) to US political functioning might best help to pull us back from such a brink?

Well, I think that’s a real challenge going forward. And again, some of these basic challenges we face seem technological as much as anything else, because we’ve had a radical democratization of information-delivery from the days…I grew up in the 70s and 80s, when you had a handful of major newspapers, and three major television networks. A lot of people on both the left and the right complained about corporate media and these media gatekeepers. But in hindsight, I think those media outlets performed a critically important function, really underpinning the more centrist politics of the postwar period. And that actually began to get undermined with the de facto repeal of the Fairness Doctrine by the FCC under Ronald Reagan, which opened the door for Rush Limbaugh, and then Fox News, and now Alex Jones, and God knows who else out there propagating conspiracy theories and lies and just sheer kookiness.

And now you have a situation where so many people get their news from a Facebook feed, basically designed to give them what they want to hear. And you saw during the 2016 election that fraudulent, fake news stories actually tended to have more stickiness online than real-life news. Social-media users actually wanted to spread the lies more than the truth. So no obvious solution presents itself for this huge challenge we face, because there’s no clear way (technologically) to just go back to the days with a handful of media gatekeepers.

Here I would stress that we pay a huge political price for the lack of any quality controls. I think we need to look at greater regulation of social media, because right now it’s the Wild West, and we saw how the Russians took advantage of that fact in 2016. And in the future, any number of other actors will no doubt attempt to do the same. So here some kind of regulation does seem necessary to preserve the public good. We should impose some of the same types of rules on social media that we already impose on broadcast media — for example: disclosing everybody who buys political ads, or holding social-media companies liable when they neglect to take down confirmed false stories, or personal slander.

We need to treat these social-media companies as de facto publishers, with equivalent responsibilities. I sense recognition of these concerns right now, but I still think much more needs to be done, including significant legislation to force this kind of accountability on the social networks. Though of course even these steps won’t fully solve the problem. We really have entered this brave new world with few gatekeepers and no clear idea where we’re headed. And only through a monumental act of will can we prevent the extremists from taking over this space even further. I mean, for one basic problem with social media: who has ever heard of a centrist troll? These people are already in fact the most motivated, even though they may not be the most numerous. So we face this fundamental imperative to mobilize moderate centrists, which might just sound like an oxymoron.

Well finally, amid your dream of a Macron-like moonshot of a campaign that could make centrism sexy again, bringing together the best of Democratic and Republican leadership, while drawing many fresh faces into politics: you might be able to persuade me to your cause, basically on intellectual grounds. But how to make a persuasive case to the most displaced, vulnerable, overwhelmed, resentful Americans that they too ought to prioritize an impeccably civil disposition? Or within a corrosive political context like our own, how might any center-right / center-left coalition most effectively fight for civility, moderation, rational deliberation? And here I wonder where a forerunner like Edmund Burke (whom I actually know from Romantic Poetry classes, not from Poly Sci) might provide a useful model for a “conservative” political style, as much as for conservative principles of governance.

Yeah, I really do hope that somebody can communicate effectively and non-threateningly, and make centrism sexy again, kind of like Macron did. Of course since Macron took office we’ve seen the challenges that pursuing a centrist path brings with it, with the Gilets jaunes movement actually uniting certain forces from the far left and far right. I sense Macron now recovering from some of that, but still facing these very difficult challenges that anybody will face. And I do think it would be great if America could find a unifying figure like Dwight D. Eisenhower who, remember, accepted the 1952 Republican presidential nomination perhaps primarily to deny the hard right the opportunity to nominate Robert Taft and take the Republican Party in a more isolationist direction. I mean, it would be great for all of us if we could find somebody with that kind of credibility and appeal, and clearly it’s not going to be Howard Schultz. So in theory, we know what might most help us, but in practice, we still face serious challenges to find somebody who can fit the bill.

But here again, if I still have any reason for hope, it comes, paradoxically, from somebody like Donald Trump (with very little history in the Republican Party) somehow winning the nomination and bringing in new voters. To me, this suggests that if we work hard to find and support the right charismatic individual, somebody much more sensible and centrist than Trump, there still could be room for him or her to pull off a similar kind of transformation, as a kind of Donald Trump in reverse. At least that’s my dream.

Photo of author by Dan Pollard