If you’d rather showbiz than smoke signals in chaos days, there is Amanda Goldblatt’s first novel, Hard Mouth. How does performing ourselves through language bolster us in the midst of calamity? Why should we expect survival to be pursued with more than ambivalence? What does it mean for an adult to runaway from the drear and obligation of emotion and family, to camp it up in the wilderness … accompanied only by an imaginary friend?

Hard Mouth follows twenty-something Denny, who flees the filtered stiflings of life for a remote mountain cabin. Equal parts perilist and survivalist, Denny is the heroine Brian of Gary Paulsen’s Hatchet might have been, had he been a woman who’d grown up in the glittery drab of nineties’ whatever.

Goldblatt and I spoke on a hot June day at Lake Storey. The mosquitos were out in droves; the bullfrogs sounded like cows. We swatted ourselves at a picnic table and talked through the afternoon. I woke up the next day with a marble-sized bug bite on my eye.

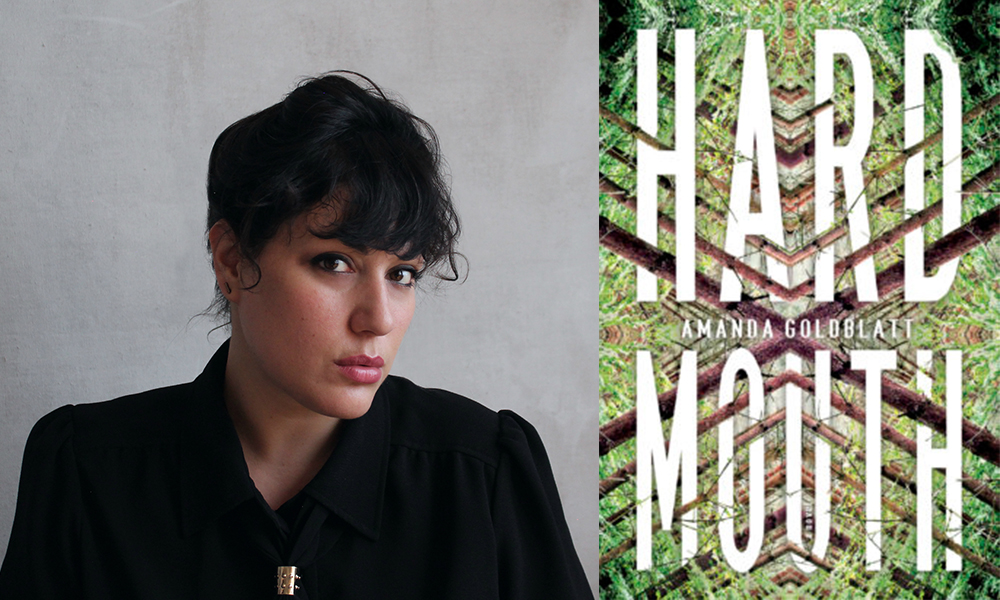

Amanda Goldblatt’s stories and essays can be found at NOON, Fence, Diagram, and elsewhere. She was a 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing Fellow, and teaches at Northeastern Illinois University. Her debut novel Hard Mouth, an adventure novel about grief, was published by Counterpoint in 2019.

¤

JOANNA NOVAK: Where did the idea develop for Hard Mouth? How did it evolve from genesis to publication?

AMANDA GOLDBLATT: It’s changed a lot. I worked on it for seven or eight years, off and on. My father was diagnosed with cancer when I was at a point in my life where I was moving from Saint Louis to Michigan to be with my partner. Grad school had ended, and I was moving into an adult life that felt no longer tenuous: things were becoming a little more stable or feeling stable in some ways. And then, while I was planning and packing, my father was diagnosed with cancer.

It ended up being okay. He went into remission in under a year. It happened very quickly — so much so that my partner forgets my father had cancer. But meanwhile, I started writing from fear, wanting to both game out what I felt like could happen and channel the intensity of my emotions.

This is the first novel that I ever tried writing. I always felt like you want the idea that’s big enough. And this felt like the idea that was big enough. When I started, it was still the first decade of the aughts, and the apocalypse felt very present for everyone culturally. What if a personal apocalypse — such as someone significant in your life dying — could convince you of a full apocalypse, a global apocalypse? At the beginning, that’s where I was going. There was a death very early, and then Denny, the narrator, had to figure out what she was going to do, now that the world was going to end. It’s a cataclysm when someone dies. It made a lot of sense to me, but the longer I worked on it, the more I felt like it just didn’t need [the global apocalypse]: one person’s individual cataclysm is enough — you don’t have to complicate it further.

Personal cataclysm is manifest in Denny’s discomfort, her fragmented sense of self. In one early scene, her father hypnotizes her and turns her into another girl, an act that speaks to his mantra about body and soul together. What about Denny’s discomfort — and her resulting disassociation — interested you?

Denny is very passive or has historically been very passive. This is a moment in her life or she’s relating a moment in her life where she could not be passive anymore — not in the noble way when people have to speak out, but in the way where she needs to dismantle herself and the terms of her life. I was really interested in thinking about the discomfort of being a person who is passive and in pain and then charting that along what it means to have acted, dismantled, gotten away, but still not being able to get away from discomfort — the discomfort of being mortal and human.

In a book filled with striking metaphors, one of the most striking is: “I’m a bending branch, who’d sooner snap than rot in place.” Despite her passivity, Denny takes an active role in her own undoing; she doesn’t plan to live more than a week on the mountain. How did you create tension around a character who’s passive, with a death wish?

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about and trying to write an essay about the difference between a runaway and a getaway and trying to figure out what Denny is up to. If someone is running away, in that manner that we talked about in the 1990s, with runaway teens, you can’t stand anything but yourself about your life. You have to remove yourself from the intolerable situation. A getaway — obviously there’s the vacation inflection of it, but there’s also the crime usage, like a getaway from a bank robbery. With a getaway, you either know you’ll return or you are fleeing triumphantly in some manner. Denny’s impulses are much closer to suicide even though she’s not an active enough character to think about that in more direct terms. Because she’s not that interested in herself and she’s absolutely not interested in her life.

Very early in the novel, something winks and then the winks just keep coming. This is a character who’s watched old movies with her father throughout childhood, and the narrative voice shows that: it’s punny, vampy, coy.

With a first-person narrator, you can’t exclude voice as a tool of character development or a way to create an aggressive affect for the experience of a story for the reader. I’m interested in the performativity of a voice and how to create that kind of pageantry, which almost makes corporeal the presence of the language. So it’s maybe not the kind of voice that you recognize as conversational, but it is presenting a show.

When it came to Denny’s voice, it was obvious to me that classic movies would be part of her cultural references. When I was developing the first draft, thinking about the idea of survivalists and the apocalypse, I was watching My Man Godfrey alone at home and I was like, the dad looks so familiar. I began to research him. His name is Eugene Pallette. He was a character actor in the end of the silent film era and the beginning of talkies, and he had this kind of self-made tragic life. He was extraordinarily popular first as a leading man — he was Aramis in the silent The Three Musketeers — and moved on to things like My Man Godfrey.

He was successful, prolific even, and so was in the tabloids a lot. I found all these old headlines — I really did a ton of research about him — about how fat he was. The newspapers really liked to talk about his big body and what he liked to cook, what kinds of things he would eat. It was really cruel, actually. But it also turns out he was a Hitler sympathizer and racist. One of his final roles was in an Otto Preminger movie in the late forties. Preminger found out Pallette was a Hitler sympathizer (who really thought the Nazis would win) and already didn’t like him, but then Pallette refused to sit at a table with a black actor, Clarence Muse, who was in the production, and so his role was cut. Things were kind of over after that. He died of throat cancer a little later. But while he was in between Nazi sympathizing and death, he became convinced that the Russians were going to bomb LA and other major cities. And so he built a doomsday place in the mountains in Imnaha, Oregon. He lived there for awhile before falling ill and returning to LA, but that became a model for Denny’s escape. And because that was a model for Denny’s escape, I wanted his presence in the novel, and his professional culture.

I was fairly conversant in that world because I grew up watching classic movies. The rhythm of that dialogue from the 1930s and ’40s really infects you in exciting ways that, 20 years later, you find studded throughout your own work because it’s your primal language. Because Denny could be raised that way, she could also be infected by that language. I began to look for moments where I could create volume in that and then moments where I would pull away because she existed in the modern world also. Through working with my agent and my editor, that voice did get pulled back some, bringing it down so that you were allowed to feel emotions instead of just the firework of the narrative. So I did work hard, especially with my agent Caroline Eisenman, on moments that felt too big, letting Gene be the big voice or the silly voice, the one who gets to use old-timey statements. Of course, that’s Denny, too. It’s her imaginary friend.

An adult’s imaginary friend — it’s sort of audacious! But Gene is so charming and — thinking about what you mentioned regarding Pallette — so bodied.

There was more body that I cut. That was something that Jenny Alton, my editor, and I talked about. He’s a large man and he was routinely made a buffoon in newspapers because of his body. And she was like, Hey, maybe you don’t want to talk about how fat he is all the time. I’m someone who believes body positivity is important, representations of different body types and abilities are important, but I had leaned in so hard on his physicality. He was a large man. So navigating how he could be so embodied and not be the true butt of the joke was something that took refinement even in the later process of editing the book. It was just so important that Denny wasn’t alone on a mountain. For anyone who’s been under extreme stress, it’s easy for your emotional landscape to feel like the ultimate reality and the potency of that — the potency of really believing your feelings — becomes more extreme the more intensely you’re feeling. And so it made sense to me, that Denny, particularly as an only child, would manifest this buddy.

The blessings and curses of being an adult only child, right? Despite how much time she spends alone on the mountain, Denny never stops thinking about her parents.

It’s not about just any death or rite. It’s not about preparing for just any kind of grief. It’s preparing specifically for a parent’s death. For only children that is an extremely sharp subject. You don’t have anyone else that you’ve been growing and developing with under the same household terms. There’s something extreme in the idea of losing your parents. If you’re in a two-parent household, when one parent dies, that’s like 30 percent of your family.

It was always going to be a family novel because of its origin. But I like the idea of an antisocial character who is still pretty tight with her parents. Often, when we read antisocial characters, they are isolated from everyone. But the truth is, people who hate people can still be close to their family.

One thing I’ve always admired about your writing is how stylish, how virtuosic the language is, image-driven yet totally clear. The language is so in tune with Denny in the moment, so committed to serving her telling of herself. I’m thinking of a scene where she’s on the mountain, in the cabin, and a tree has just broken the roof. And suddenly all the sentences are clipped of subjects.

Yeah. I was asked at different times throughout the processing of the manuscript whether I wanted to put in subjects in that litany of sentences. I didn’t ever want to. I don’t necessarily think Denny is a really good storyteller, but when you’re in the presence of a really good story teller and they’re sort of re-performing something like urgency, they will do things like that, whether or not they’re thinking about it.

Denny is very much in her body — she’s fucking and shitting and bleeding — but also disconnected from her body. Did you have particular concerns about how you were bodying her?

Denny is not like a high femme. While she’s connected to her sexuality, she’s not particularly connected to any idea of gender. She’s not attracted to girly things, to the conventionally feminine. There’s almost no description of her body or her appearance.

That was striking to me.

I often find it dreary to read physical descriptions of characters unless it directly ties into what the narrative is about. I was interested in writing a character who was highly sexual but not highly gendered. She is aware that the trappings of what she wants to do — having a pickup truck, eventually a gun — are male or phallic-seeming in some ways. She has very little femininity, but she is attracted to men. I’m not sure whether I agree with the idea that this allows, particularly, a cisgender woman to think more squarely about her body as a machine or a thing, divorced from the idea of what a body looks like, what a body should be like, what we expect her body to be like. But it’s in this way that she’s allowed to shit, and she’s allowed to pee, and she’s allowed to have her period, without it encroaching on some more glamorous idea of womanhood.

Often when, especially female writers, approach those topics, it becomes spectacle —

Like, it’s transgressive.

There are such distinct climates in the novel: air-conditioned, laboratorial, wilderness. What was it like moving between those spaces?

I was interested in the idea of making Suburban Home and Mountainous Away a binary. Especially in the D.C. area, air conditioning is everywhere and really aggressive, particularly in the late summer. When I was growing up, there were a lot of window units and not much central air, so when you were near air conditioning, it was really blasting you, and when you were not, it was really sweaty and sticky and uncomfortable. D.C.’s on a swamp and it’s not so deep in the south that it everyone has front porches or air conditioning or both. D.C. is not really equipped for heat.

And I was always really drawn to the wilderness. This particular mountain is not consciously set in a particular place because I didn’t want to hang something like that on it and, frankly, for Denny it doesn’t matter. My parents and I spent a lot of time in West Virginia, Pennsylvania. I want to sleep-away camp a couple summers in a row in Pennsylvania, in the Poconos — deciduous forests, not super high mountains, but some mountains, some switchbacks. Denny’s mountain became a collage of those things. The trick about having a retrospective narrator who also is not a wilderness expert is that she doesn’t have to get things right.

That inexpert quality leads to some great description. Immediate, unfussy.

There was a moment during copy editing where the editor asked if I wanted to close the space between “black” and “bird.” I was like, well, Denny wouldn’t know that it was a blackbird; she would know that it’s black in color.

Speaking of point-of-view, can we talk about violence? What were the challenges in putting the brutality on the page, especially as Denny is recounting it?

Once I had located Denny and who she was and what she sounded like, it was easy. Everything was easy to make happen because she was a juggernaut of her own invention. And so because she wasn’t going to offer anything in explanatory terms, anything could happen, and it could all feel as big or as small as she made it out to be. So that part was easy. I in fact included more sex and death then I originally thought I would because I saw I could get away with it and I was thinking about the way that adventure novels work and how often things are matter-of-fact. Though most adventure novels are oriented towards survival. This one is not oriented toward survival at all.

What adventure novels were important to you?

I did read Hatchet a few times. I really liked those in-the-middle-of-the-wilderness books when I was growing up; they felt really formative to me. One that is an adventure novel but not a typical boy’s adventure novel that I was thinking about recently is this book called Baby Island. It was about these two girls who were on a steamer ship or a cruise ship on their way to, I think, a father, and their ship is caught in a storm and they are washed away — with other passengers’ babies — onto this tropical island. In a lot of ways it’s fucked up, right? The survival novel for girls, the adventure novel for girls, is where they have to take care of children —

Surprise!

— not wrestle a bear. I have dipped into but have never been a real allegiant to Jack London. I had this gig writing reading guides for websites, in which I would either read books or watch movies and then provide a guide that students could use to help refine their understanding of the text. (I was very unemployed, and it was an option, and it paid okay.) One of the projects I did for that was Herman Melville’s Typee. It’s basically about an exoticized tribe of people and the westerner that shows up. So working on that, I was aware of the immediacy or urgency of figuring out what to eat, what’s not poisonous, finding shelter. That’s stuff I’ve thought about. When I was thinking about violence, I was just looking at it this morning, actually — High Wind in Jamaica by Richard Hughes, which was released by NYRB, with a Francine Prose prologue. It’s about a bunch of children who are being shipped from their colony home back to for school, basically without their parents. At some point, one of the children just falls and dies and it happens in like three paragraphs. It’s like, he fell from a great height and headfirst. That quick. I thought a lot about that tonality when I was working. I read [High Wind in Jamaica] for the first time years ago and I thought a lot about — depending on narrative perspective and distance — what you can kind of get away with in those terms. Of course I complicated that by how alternately disembodied or embodied Denny is. That changed things.

The novel alludes to these moments of childhood entertainment — the roughing-it quality of, say, The Boxcar Children.

I was very in love with The Boxcar Children. This gets back to the idea of the getaway or the runaway, the idea — particularly for a child — of finding yourself somewhere where there are no parents and you need to figure shit out. Denny’s creating that for herself belatedly.

That feeling doesn’t go away, then, when people get older — wanting to run away, to escape?

It eventually becomes a midlife crisis and then from there you’re supposed to be too exhausted to try after that. It’s an escape without being escapist. Denny is someone going through a very human trauma, within a privileged context. I don’t know if the novel is about some kind of self-empathy or just some kind of reckoning. I don’t think it’s about kindness. I don’t think it’s about catharsis, but I do think … Many of us have an impulse to want to escape, but know it is not responsible to do so. Denny is taking her privilege and opting out, but it’s imperfect and impossible, and maybe that is instructive to her: there is only endurance in life.