Brazilian writer João Gilberto Noll’s Atlantic Hotel is a surreal journey — by bus, foot, and wheelchair — around southern Brazil. The pages fly past in this short novel; the narrator travels from a murder scene in a hotel, to the beach, to a brothel, and through an apocalyptic storm, before waking up to the amputation of his own leg. And that’s just in the first half of this 140-page book.

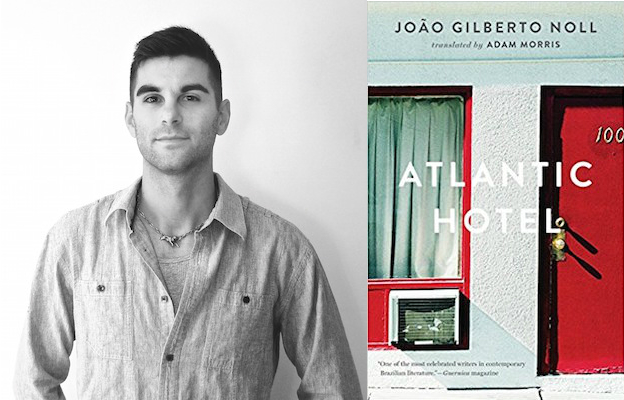

Noll died on March 29 at the age of 70, just two months before the publication of Atlantic Hotel in English. While Noll has been widely published in Brazil, this is only his second book in the United States. Translator Adam Morris and publisher Two Lines Pres, who also worked together on Nolls’s Quiet Creature on the Corner in 2016, now bring Atlantic Hotel to an American audience. The narrators in both of these novels are vagabonds who pursue each new activity without regard for the past or the future, and in both, the reader gets swept up in the narrator’s unparalleled ability to be diverted.

Noll’s books are wild, violent, and fast-moving, qualities that Adam Morris has beautifully channeled in his English translations. On the occasion of the publication of Atlantic Hotel, I wrote to Adam Morris to ask him about his experience translating Noll’s work.

¤

NATHAN SCOTT MCNAMARA: When and where did you first read João Gilberto Noll? When it came to translating his books, was it clear where to start?

ADAM MORRIS: My earliest retained memory of reading Noll is when I was in Rio for the summer of 2011 to work on my Portuguese and to get to know the city. I was pretty broke, so I spent a lot of time rifling around in used bookstores, called sebos in Brazilian Portuguese. Sebos aren’t like the fancy Bay Area used bookstores I’d gotten accustomed to: they’re way more hit-or-miss, so it’s very exciting when you find what you’re looking for. Often you end up leaving with a bizarre assortment of things you’d never otherwise read. But somewhere off the beaten track in Copacabana I found two weather-beaten Rocco editions of early Noll novels: Bandoleiros and O quieto animal da esquina. At a certain point that summer I gave up on my classes and spent most of my time reading on a bench at the botanical gardens, on the metro and the bus, and at the beach.

I guess now that I think about it, memories of this experience are part of why I suggested that Two Lines publish O quieto animal da esquina. The narrator starts out as an urban vagrant who drifts between sebos, the public library, and louche movie theaters. Likewise, when I first became acquainted with Noll, I was a literature student low on funds and spent most of my young adulthood hanging out for too long in inexpensive cafés, going to cheap double features and drinking in dive bars only when I could afford it. Similarities between me and the narrator pretty much end there: my own lived version of the aspiring-writer cliché is pretty tame, and nothing like the strange and violent flights of Noll’s protagonists. But his voice drew me in.

The most common comparison (for English readers) I’ve seen for Noll’s work is David Lynch, due partly to Noll’s dreamlike movement between surreal scenes. For those of us less familiar with Brazilian literature, what tradition does Noll come from? Does he have identifiable influences, Brazilian or otherwise?

Well, I’m partially to blame for the prevalence of that Lynch comparison. I’m a big Blue Velvet and Mulholland Drive fan — who isn’t? I keep trying to push a George Saunders comparison to Noll, but as far as I know, nobody else has been running with that. Something about Lynch is resonating, and for good reason: eerie non sequitur and unexpected changes in emotional timbre are signatures of both Lynch and Noll. What I think they both do so well is to concatenate nightmarish aspects of the mundane world with scenes from dreams and hallucinations. Neither of them is interested in maintaining the boundary between the real on the one hand and the surreal or the imaginary on the other: those things are coeval parts of existence for the subjects of their fictions.

Your question about how Noll fits the Brazilian canon is not easy. Noll had said that he and some of his contemporaries were actually breaking with the Brazilian literary tradition. The 19th-century style of realist and historical novels lingered on for a while longer in Brazil than it did elsewhere, and after that came the regionalist period in the 30s, when depictions of the land and its diverse inhabitants were part of a literary project of reconciling diverse national experiences with a unitary national identity. Regionalism was in several respects a continuation of 19th-century literary nationalism, and is a phenomenon not limited to Brazil, but visible elsewhere in the Latin American literary tradition. Anyway, Noll rejected all of this.

Noll often identified Clarice Lispector as an important influence. And Nelson Rodrigues, whom he described as a writer attuned to the unconscious of the Brazilian middle class. But I think it’s more helpful to consider the question from a global perspective. It’s easy to forget this when living in the United States, but the minute you walk into a bookstore in another country, you realize how much more other literary cultures read in translation. Camus and Kafka were quite important influences on Noll, as they are for many writers who come after them, including Lispector. Noll admired Sartre and once described Beauvoir’s Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter as “biblical” for him. So it shouldn’t be surprising to find existentialist themes in Noll’s work, as there were in Lispector’s.

In just 140 pages, the narrator of Atlantic Hotel takes us through a remarkable number of sexual and violent encounters. Among other things, he’s present for four separate deaths and an amputation, none of which he anticipates. How does Noll keep the reader with him through so much blindsiding action?

Speaking technically, the way that Noll manages to keep the reader and the story together is by deliberately overemphasizing what Roland Barthes called the proairetic code of narration, which is made up of those events and descriptions that propel the action of the plot and are not intended to disclose any meaning. They indicate that things are in movement, or that something will happen next, or eventually, or inevitably. A convenient example is a knock on a door. Often Noll surprises or manipulates the reader by foreclosing the events that this narrative code sets up by constantly redeploying the proairetic code without the benefit of the hermeneutic code, which refers to the disclosure of withheld information that will satisfy the reader by allowing events to add up to a coherent narrative or by solving a problem or mystery the text presents. For example, the protagonist of Quiet Creature on the Corner is a squatter who lives in precarious circumstances with his mother and has just lost his factory job. Before the text can resolve or address those problems, he rapes his neighbor and is hauled off to jail. But before he has any reckoning with the law, he’s plucked from his cell by an older man and whisked away to the countryside. Noll short-circuits the way readers are conditioned to assimilate plots by privileging the proairetic code without the benefit of any hermeneutic codes that would help to solve the text’s enigma. Instead, the narrative only becomes more enigmatic.

Do you suspect Noll had much of a plan when he sat down to write a book like Atlantic Hotel (or Quiet Creature on the Corner)? What do you know about his method?

Noll used to say that he never had a plan for the novels when he wrote them. He had no final destination or discrete trajectory. Unlike César Aira, however, he does admit to rewriting the resulting narratives. If we take him at his word, Noll’s texts are produced in a way similar to the proceedings of psychoanalysis. He has stated as much in interviews.

What’s the hardest part about translating Noll? What’s the most fun?

This is a dual question. First there’s the challenging aspects of reading and talking about a certain writer’s work, and then there’s what I find to be the most difficult part of translating. With every writer I translate, these two series converge in a different way. In Noll’s work, it’s a matter of voice.

Noll demonstrated in his early short stories that he could write elegantly and in a more refined postmodern style that makes those stories uncharacteristic of his overall corpus: it’s easy to imagine them having been written by someone else. The style of Atlantic Hotel and Quiet Creature on the Corner, however, are unmistakably his. Noll is very present in the voices of these novels’ narrators. He even used to say that his novels were all about one character who emerged from his own life experience, although they’re not autobiographical.

In Quiet Creature the narrator is a young, aspiring poet. His voice reflects this: his run-on narration is at times slowed by clumsy or stark descriptions, and at others is punctuated by surprising and arresting poetic images. It was difficult to reproduce this. It required a lot of listening to the narrator and trying to hear his voice.

The most fun part of translating Noll is certainly his wry and mordant humor, which sometimes appears even in the most extreme and violent scenes.

How did you happen to start down the path of translation? When and how did you learn Portuguese, and what would you say is the difference between being able to fluently speak the language and being able to translate a writer like Noll?

I became a translator in an almost accidental way. I learned Portuguese mainly in the classroom setting, and a few years later I was named one of the winners of a translation contest that I entered without ever expecting anything to come of it. The outcome of that experience was my translation of Hilda Hilst’s novella With My Dog-Eyes.

I don’t think there’s a strong correlation between how well a person speaks their second or third language and how well they translate from it. What matters more is their command of the target language, in my case English. Good translators have a strongly developed sense of style acquired from years of reading, but can exercise restraint by not imposing their own style, if they are writers, onto works they translate. A highly regarded translator I know told me she heard a lot of me in my translation of Hilst. I don’t think she meant it to be disparaging, but I was disappointed by that comment. As a translator I want to go unnoticed.

If you have the opportunity to translate more of Noll’s books, what would be the next one you would turn to and why?

I’ve only begun to think about this. But most likely, the next book or two would likewise come from the same early-middle phase of Noll’s career, that is, the late 80s and early 90s, such as Harmada or A céu aberto. These texts would begin to flesh out for readers a more complete idea of what Noll was up to, and of what his concerns were as a writer.

Why do you want to bring Noll’s books to an English-speaking audience? Why should people read him?

Noll’s work hardly needs my approval: his literary reputation stands quite well on its own. In Brazil he is considered a titan of 20th-century letters because of his stunning originality. I happen to agree, but American readers can decide for themselves.