Where should any Adam Smith-style capitalist want to see our economy much more closely regulated — out of respect for healthy market competition? Where might data-driven firms today increase their profits not by producing more efficiently, not by developing better goods, but by discriminating more effectively? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Joseph E. Stiglitz. This present conversation focuses on Stiglitz’s book People, Power, and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent. Stiglitz is an economist and a professor at Columbia University. He is also co-chair of the High-Level Expert Group on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and Chief Economist of the Roosevelt Institute. Recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (2001) and the John Bates Clark Medal (1979), he is a former senior vice president and chief economist of the World Bank, and a former chairperson of President Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers. In 2000, Stiglitz founded the Initiative for Policy Dialogue, a think tank on international development based at Columbia University. Known for his pioneering work on asymmetric information, Stiglitz’s research focuses on income distribution, risk, corporate governance, public policy, macroeconomics, and globalization. He is the author of numerous books, the most recent of which include Globalization and Its Discontents Revisited, The Euro, and Rewriting the Rules of the American Economy. His latest book, Rewriting the Rules of the European Economy: An Agenda for Growth and Shared Prosperity, will be published January 28.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could you first sketch some foundational sources of US wealth-creation that we should be reinvigorating right now, to help address some of the biggest present-day and near-future challenges posed by globalization and technological innovation? And along the way, could you start to flesh out why we shouldn’t presume a basic tradeoff between democratic equality and dynamic growth — but instead something closer to a direct correlation?

JOSEPH E. STIGLITZ: This book begins by asking why our standard of living has risen so much higher over the past 250 years, after centuries of not really changing much at all. We have data stretching back hundreds and hundreds of years, which show no significant change basically until the 18th century’s end, when economic growth starts soaring. You see not only increases in income, but in standards of living — with life expectancy doubling, with almost any quality-of-life measurement you can think of doing something similar. And this book traces a lot of those dramatic gains back to two foundational features of the Enlightenment: its scientific advances (helping us to systematically uncover nature’s mysteries, and to understand physics and chemistry, and eventually to develop all of the technologies that help us to decode DNA, and to make such amazing medical advances, and to produce electricity, and telephones, and then cell-phones), and its modern modes of social organization (pushing us from simple agricultural societies to complex manufacturing and service and innovation economies on a global scale).

For both of those basic Enlightenment gains, we need a shared commitment to rule of law, and regulations for markets, and governing mechanisms such as our separation of powers. We need ongoing advances in social organization to keep increasing our standards of living. And behind both this scientific innovation and this improved social organization, we also need the common element of ascertainable truth. Through science we can ascertain the truth about extremely complex phenomena like global climate change. Through rational political debate and empirical social-science research we can devise the best institutional mechanisms for resolving disputes, and preserving judicial independence, and promoting an independent media that helps to check against abuses of public and private power. We need this whole set of truth-discovery and truth-assessing institutions.

For one broader social-organization topic, what have the past 40 years of empirically minded economics research (and of ordinary lived experience) taught us about the insufficiencies of markets to value certain types of crucial long-term investments, to protect against certain types of negative externalities, or to manage the acute challenges posed by society-wide technological transformations? And in each case, what distinct capacities can government bring to addressing such concerns — perhaps particularly by coordinating efforts among the private sector, civil society, and countless individual citizens?

First, I’d stress the need to take on our biggest challenges collectively. We couldn’t have defended ourselves against Japan in World War Two, or against the Soviets during the Cold War, by just operating as individuals in the private marketplace. We needed government to organize us collectively. And similarly, individualized market incentives wouldn’t have led us to discovering DNA or developing the Internet.

Second, I’d point to how, in today’s complex society, people can’t just fend for themselves. A 17th-century farmer definitely had to contend with the vagaries of the weather. But people now can lose their livelihoods because of a recession or just a brief economic downturn — through no fault of their own, and with no farm to turn to. So we need significant mechanisms (much more than our society recognizes today) for social protection. We can’t just leave individuals entirely on their own to provide for their retirement. We can’t just let children born into poor families wind up with inadequate educations and no real job prospects. But if we want a decent society where those kinds of situations don’t happen, then we need to invest much more in our collective future.

Similarly, complex societies require significant regulation. Some of these regulations just have to do with coordinating everyday activity. A city can’t function without stop lights, and without its residents agreeing to this principle of who can go first, and who goes later. And a complex interdependent economy like ours has lots of different ways in which one person might impose costs on others. Economists call these externalities. We now have, for example, every society enforcing some sort of environmental regulations. If we didn’t, Los Angeles would soon become unbreathable — just as, in 19th-century London (or in many cities around the world today), people could die from lack of environmental regulations and enforcement. Or consider what can happen through exposure to particulates. We don’t think of coal companies as deliberately murdering people, but adding particulates to the atmosphere does have the effect of weakening some people’s lungs to the point of them dying. So again, as a society, we need to regulate externalities of these kinds.

Even the positive stimulus of personal entrepreneurial activities depends so much on appropriate macroeconomic management and regulation — none of which individuals can just undertake by themselves. But this book also emphasizes many forms of people power that don’t rely so strongly on government, and that we also should recognize and celebrate. We need collective bargaining on the part of workers to redress imbalances of power, and collective class-action suits so that ordinary consumers can protect themselves against big companies. When people get together and act cooperatively, that makes society as a whole much better off. I mean, the only part of our financial system that did not engage in massive bad behavior before the 2008 crisis was our credit unions. The only part of our financial system that actually did what it should do after a crisis (lending to small- and medium-sized enterprises) was these same credit unions, run as cooperatives.

So with major civilizational transformations of the past 40 years still in mind, could you make your case for why we need structural political and economic reform (not just incremental technocratic fixes) at present, and why defeating a disastrous Donald Trump administration wouldn’t by itself provide a sufficient course correction? What do Never Trumpers in the Republican Party, or neoliberals among the Democrats, still fail to grasp about the necessity to promote basic economic security, full and dignified employment, egalitarian and inclusive participatory democracy, and environmental sustainability (all at once) as we seek to construct a more stable, dynamic, globally competitive economy?

Right. So once you recognize the importance of collective action, then you start thinking: Well, how can we do even more of that? And once you recognize all of the ways we’ve just discussed in which government sets the rules of the game, you realize the need for an active government to keep our markets and our politics functioning fairly and efficiently.

The US has become one of the most unequal democracies among the developed countries. We might still talk about “one person, one vote,” but we all know that some people have much more influence than others. We all know that inequalities of economic power inevitably get translated into inequalities of political power. That happens in any society, but especially in present-day American society. And when you then factor in that we also have more economic inequality than any other developed country, you start to sense the extent to which our political system amplifies certain voices over others. You start seeing how we operate less on the principle of “one person, one vote” than “one dollar, one vote.” Obviously, this opens up possibilities for state capture by rich corporations. And obviously we see the consequences of that capture today. We’ve already experienced a catastrophic financial crisis in which the big banks first bought financial deregulation, and then bought themselves a massive bailout. And those same strategies apply with globalization, with the US imposing rules that have worked very well for big corporations, but not for ordinary Americans.

So in school, we might learn about the importance of checks and balances. But that system of checks and balances doesn’t work when you already have substantial economic inequality. Somehow or other, those with enormous wealth figure out a way to capture the state. Those kinds of concerns drove the 19th-century Progressive movement, leading to our antitrust laws. But we’ve now returned to the kind of inequality that marked the Gilded Age. And just like 125 years ago, the market will not solve our inequalities. The market will not address the inaccessibility of better education and better jobs and better quality of life. The market will not solve our climate-change crisis, or our diabetes crisis or our opioid crisis — just like it didn’t prevent or stop our financial crisis. The markets themselves created each of these problems, and will keep creating new problems so long as corporations have captured crucial state functions.

Here again, amid the spectacles of Donald Trump’s dysfunctional presidency, I appreciate your persistent focus on structural concerns, your reluctance to dwell too much on Trump’s norm-breaking antics (many of which any subsequent administration, from across the political spectrum, will hopefully reject). But given the importance you assign to knowledge-production and to social cohesion in generating broad-based prosperity, I do want to single out your concerns about Trump’s assaults on our institutions and norms of truth-discovery, truth-telling, and truth-verification. Could you describe, from an economist’s perspective, what most frightens you in Trump’s undermining of any shared epistemological baseline for American society, and for cooperative international engagements?

To me, the greatest danger so far posed by the Trump administration comes from this undermining of our institutions of truth-discovery and truth-verification — particularly, again, in terms of the two basic pillars for advancing our standards of living: science and social organization (or democratic coordination). And more generally, we can have different opinions about how best to address a difficult problem, but we should at least agree on the facts of the situation. Or in international affairs, we should at least fulfill our stated commitments, so that our foreign partners have good reason to trust us.

In either case, we shouldn’t have a president openly lying about the crowd size at his inauguration. We shouldn’t have administration officials appealing to an alternative reality coming straight from President Trump’s fantasies. Our complex and interdependent society can’t function if the president gets to make up the truth as he goes along, and to impulsively and unilaterally dictate every aspect of our decision-making process. That undermines our ability to cooperate, and to work with other countries.

Right now, for example, we face this very distressing question about a potential military conflict with Iran. Clearly, what our president says on this topic has no credibility, either domestically or internationally. President Trump very well might have received information kept secret from the rest of us, but how could we ever trust him if he claimed the need to act on confidential information now? We typically have trusted our leaders to operate from that kind of informed perspective. We know they can’t share everything. But it would be foolish to trust President Trump with any confidence at this point. And we also need to recognize a much broader social problem here — when we no longer have a shared baseline from which to agree on the facts.

For one additional example then of our present-day politics and private markets undervaluing truth-discovery and truth-ascertaining initiatives, could you discuss the importance of public investment in basic scientific research? Could you illuminate the hypocrisies of, say, social-media executives completely dependent on the Internet, GPS, and touchscreen technologies — but posing, at least in certain contexts (when not calling for infrastructure investments, new educational initiatives, or special protections against Chinese rivals), as self-sufficient libertarians? And could you point to the diminished societal benefits of costly research conducted by private firms, with firms incentivized to keep such discoveries to themselves, and to deploy any corresponding innovations to further concentrate their own power (presumably at everybody else’s expense)?

The hypocrisy actually runs even deeper than what you just mentioned — first because these companies routinely draw upon some of the best-trained people in the country, who have benefited from subsidized graduate educations. Most of our graduate students get a free education, with government research paying for a lot of that. And an additional source of US success always has come from talented but poorer students seeing a path to upward mobility — again with government funds playing a big role.

A second source of hypocrisy comes from all of these successful companies relying on the government to enforce contracts and maintain the rule of law. A true libertarian would operate within jungle-like conditions. And I’d say: “Good luck trying to create Google in the middle of the jungle!” We benefit greatly from having been born in a society with high-level social organization including an established rule of law — and we shouldn’t forget our luck, or our reliance on that public good.

Ironically, you of course do see these supposed libertarians also lobbying the government to protect their intellectual-property rights, to expand these rights, to design international trade agreements providing these firms further protections against foreign governments regulating their liabilities. So they certainly do rely on a wide-ranging US government, even when saying we need less government. And the history of basic-science research makes this all especially clear. Many of our AI innovations come out of mathematics. The private sector never has adequately valued these basic advances in mathematics, because for a long time mathematical discoveries might remain just too abstract, just too general, waiting for more practical applications. Think about the beginning of computers with the Turing machine. The British government effectively funded that research, especially in its earliest stages. We shouldn’t expect private firms to do that. And we shouldn’t want them to — because you don’t want new discoveries closed off to a very few firms thinking about a very narrow range of commercial possibilities. So most economists recognize the importance of government funding both for basic research and even for a lot of applied research.

Here we start pivoting towards this book’s broader concerns about various types of economic concentration, again particularly in the tech sector. So could you first take some of today’s most conspicuous symptoms of market concentration (firms’ ability to sustain prices far above market costs, firms coercing customers into pro-business arbitration settlements, dominant firms impeding potential challengers’ market access, dominant firms preemptively merging with emergent rivals, dominant firms threatening spurious patent lawsuits or gumming up interdependent networks of innovation), and describe why any advocate of market competition should see clear need for significant change?

We can start with the most obvious symptom of an industry only having one, two, or three firms. Then we can factor in the deception when the same conglomerate owns multiple firms that use different names — so that it looks like, for example, Duane Reade competes with Walgreens. Then you get situations like Facebook buying a firm with a slightly different function such as Instagram.

But now returning to that basic situation of there being just three or four or five big tech companies: these companies may compete at the edges, but that doesn’t come close to the textbook model of perfect competition that some economists still like to discuss. Instead, this limited pool of companies has significant power to raise prices far beyond the costs of production. Consumers just don’t have any choice. We probably all know the experience of getting angry with your cell-phone company or your cable company because of service problems in some form or other. So what do we do? We switch to one of the few other cell-phone companies, and find them just as bad. Or with airlines, if I want to fly nonstop between two cities, then I probably can rely on two or three companies at most. That gives these companies great power to raise prices. Sometimes they coordinate, through a form of tacit collusion. And they certainly sense why blocking any new competitors might serve their mutual interest.

Economists have now studied these relationships between price and cost of production in a wide range of industries. The credit-card industry stands out as one of the worst. You might pay a 29% interest rate on your credit card, even though providing you with that credit only costs the bank about one percent. An additional 20% charge for a default on repayment just adds to their huge profits. Of course some competition between Visa and Mastercard and American Express still might happen — but most of this competition gets dissipated through excess advertising and other activities with little social (or customer) benefit. As an end result, US merchants likewise pay a disproportionate amount for credit-card transactions, and those costs again ultimately lead to consumers paying higher prices. India, by contrast, recently eliminated these costs for merchants.

So from an economist’s perspective, what else about today’s market concentration particularly calls out for reinvigorated antitrust legislation and enforcement: preventing consumer price-gouging, but also preventing firms from attaining dominant market share in the first place, or breaking up conglomerates taking on dual roles as platform providers and content producers, or requiring more persuasive projections of proposed mergers’ society-benefiting efficiency gains?

Well that broader legal approach goes back to Louis Brandeis and to democratic theory from the Progressive Era. It says we need to remain vigilant about not just concentrated economic-market power, but also political-market power. Its updated version says, for instance, that if the same company owns a community’s television stations and radio stations and print media, and operates a significant share of the advertising market, that company probably has an excessive influence over the marketplace of ideas.

That may depart from any strict consumer focus, for example when we consider monopsony — where you have disproportionate market power as a buyer rather than a seller. So, for instance, Walmart or Amazon might have enough power as buyers to drive down the cost of the goods they buy, and might even pass along some of these cost reductions to consumers. But now a lot of small producers will face significant problems.

Monopsony concentration likewise plays a particularly corrosive role in our collective lives due to how monopsony labor-market conditions diminish workers’ bargaining power. Could you describe some ways in which the binds that individual workers might face (in terms of a limited ability to find alternate employers in their fields, or to relocate out of industries or regions with few prospects, or to switch jobs or careers amid a lived context of pressing debt obligations, of non-compete contracts enforced by employers, of non-poaching agreements illicitly maintained by employers) steer labor markets away from efficiently providing desirable workplace outcomes for so many of us — and why the broader economy suffers as a result?

Over the past couple of generations many economists have relied on a model that you might say underlies neoliberalism. This model assumes perfect competition in our labor markets, and takes for granted that workers can easily move from one location or industry or set of skills to the next. But if we had perfectly competitive labor markets, we wouldn’t have any low-wage regions in the country. Everybody would receive wages corresponding to their skills, and would acquire new skills whenever that seemed in their self-interest, and would move elsewhere when they saw a better opportunity. But we all know that some places and some communities in this country have suffered a great deal in recent decades, and that people from these places face significant impediments to mobility. Companies of course have recognized these same facts, and have pushed down wages further in these places. Some companies have even deliberately relocated to these places, in order to establish monopsony power and pay a lower wage and bargain less with workers. Sometimes companies might express their commitment to such a place, but their monopsony position just intensifies the inequality.

Globalization also of course can weaken workers’ ability to engage in collective bargaining. If our trade policies then give firms stronger property-rights protections against regulation when they invest abroad, that also encourages firms to move out of the US and find workers elsewhere. But even more frequently, firms can just use this threat of moving abroad as a cudgel against Americans workers. Firms will say: “If you won’t accept a wage cut, or if you don’t accept your wages rising one-percent slower than productivity gains, then we’ll move out.” In a monopsony situation, these workers have no recourse. They can’t just move to San Francisco. And most of them don’t want to. We typically feel strong attachments to our local communities, even when they don’t offer many jobs at our particular skill level.

In terms of illegal non-poaching agreements (which again prevent workers from competing in any perfect or even fair market) maintained by big-tech companies like Apple, we would never have even known about these employment practices without whistleblowers coming forward to expose them. And we have no other way to gauge how common these kinds of wage-reducing agreements might be in our economy.

Still in terms of corrosive consequences from concentrated tech power, unprecedented capacities for data-collection likewise threaten, you say, not only those with “something to hide,” but our whole society’s foundational emphases on equality and autonomy. Today’s enhanced data-collection allows for unjust and inefficient price discrimination (with those most in need forced to pay the most), for predatory manipulations of our genetic/medical profiles and our emotional vulnerabilities, for incumbent data-hoarding firms again to stymie would-be rivals — and to extract corresponding wealth and power from the rest of us. So why should any self-respecting Adam Smith-style capitalist take quite seriously European governments’ pioneering efforts to regulate this emergent data-driven economy: out of respect for personal-privacy concerns no doubt, but also out of respect for healthy market competition?

To start with, one fundamental principle of market efficiency comes from this idea that everybody pays the same price for the same goods. The marginal value of these goods stays the same in every use. That allows markets to efficiently find the appropriate prices for these goods. But when companies today can assess how much each particular individual might willingly pay for this good, they can start charging different people different prices. Picture a traditional bazaar, where you might haggle over a rug’s price. This could make life quite difficult — with the rug seller trying to determine how much you would willingly pay, and you trying to figure out how low the rug seller would sell it for. Those kinds of guessing games don’t make for an efficient market.

But now, in our modern data-rich economy, an online office-supplies seller knows precisely how far a particular customer lives from the nearest store. That seller knows the nature of the competition in a buyer’s immediate vicinity. Especially in poor neighborhoods, sellers know they face the least competition, and can charge the highest prices. These sellers might call this simple profit-maximizing, not discrimination. But we do have laws against this kind of price discrimination. These laws say that you only can justify charging different prices based on differences in costs of serving the customer, say in delivering to the customer. But we haven’t enforced these laws for a long time, and have instead wound up with new forms of price discrimination. If you have enough data, you can become more profitable — not because you produce more efficiently, not because you produce better goods, but because you discriminate more effectively.

Tech-driven workplace automation likewise brings about its own unprecedented modes of concentrated economic production, prompting obvious concerns for a wide range of occupations. Could you again describe some broader structural threats that automation also poses to our economy as a whole — particularly as it raises prospects for a significant and perhaps irreversible drop in consumer demand?

In principle, innovation (specifically automation) could make our society wealthier, and could leave everybody better off. But we do face a situation right now where some types of innovation might decrease the overall demand for labor, or for a wide swath of labor — for work that might require more or less skill, but that in any case can be replaced by a robot. Here particular groups of workers might find themselves much worse off, unless we develop measures to protect them and to protect us. And like you said, from a macroeconomic point of view, if enough people lose spending power, then aggregate demand could drop, and the whole economy might suffer.

One approach to understanding the Great Depression argues that something very similar happened to many farmers. We first had substantial increases in agricultural productivity, so that we needed far fewer farmers to produce our food supply. As a result, even as agricultural production soared, some farmers’ incomes decreased by 50 to 75 percent — so that they couldn’t buy the goods produced in cities. And to return to the topic of imperfect mobility, many of these former farmers had long-term difficulty moving to another sector. They had to retrain. They had to switch locations. They had to get new housing. For a whole variety of reasons, this all slowed down the economic transition, and took us towards the Great Depression — with only World War Two getting us out of that.

Given the essential role then of employment in supplying a sense of personal dignity, and in fueling a virtuous macroeconomic cycle of middle-class demand-driven growth, one might hope for Americans across the political spectrum to embrace your call to establish a basic right to a guaranteed job for all able-bodied and willing workers — and to facilitate quality-of-life gains for middle-class workers through corresponding pro-family regulations and support. And in terms of how we should pursue full employment, could you outline your emphasis specifically on fiscal policy (especially on high-multiplier initiatives), alongside your concerns about monetary policy at times incentivizing further job-eliminating automation?

Yes. It seems quite clear at this point that monetary policy will not get us to full employment. Many people might ask: “Wait, haven’t we reached full employment?” But the US employment rate today has dropped below its historical norm. A lot of potential workers have basically left the labor force. And even if we have approximated full employment for now, we know that for a period of five or six years we relied excessively on monetary policy, without reaching full employment. So I do see a greater need for fiscal policy, which can include the types of investments we’ve discussed: such as investments in scientific research, in education and in social protections for workers, in infrastructure (and especially right now in the transition away from a carbon-intensive economy).

Each of these kinds of investments can both stimulate the economy and increase the employment rate. We also of course need to think about people who have inadequate jobs, alongside people with no jobs. And since World War Two, even when we have come closest to full employment, minority workers, especially young people from minority groups, still often can’t get as much work as they want or need.

So most broadly, I would say that if we can shape monetary and fiscal policy in just the right way to make sure everybody who wants a job gets a decent job, great. But the historical record makes me pessimistic about that approach. So instead I’d go back to our 1946 Employment Act, and strengthen its mandate, and require that the US government ensures full employment. We haven’t lived up to that basic commitment, but I think we should. Part of this might entail providing a guaranteed job. And we do need public investment in so many places right now. We have lots of opportunity for cleaning up our cities, for beautifying cities, for creating parks, for making our country more livable in many different ways. We often fail to appreciate the enormous legacy of our Great Depression-era public-works programs, which helped to build much of our modern infrastructure and our national-parks system.

And then part of providing dignified employment also means ensuring Americans can get the training that allows them to keep moving into new jobs elsewhere in the economy — because we want upward mobility, not just for workers to stay in these specific jobs we create. That’s another important part. But your question about the dignity of work gets at the core idea that I’ve tried to get across.

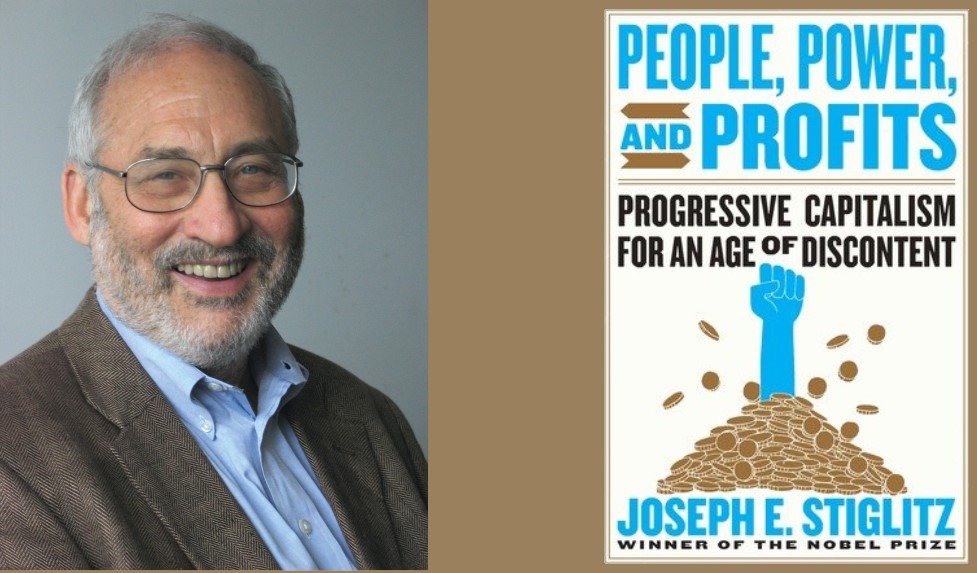

Photo of Joseph Stiglitz courtesy of Dan Deitch.