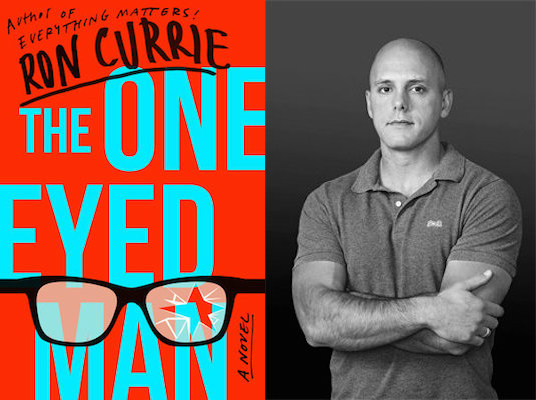

Author Ron Currie ponders many of life’s great mysteries. Speaking to me via video stream a day before his 42nd birthday, he reflected upon the perils of getting older, posing the oft neglected question regarding ear hair: “What the fuck biological function does that serve?” Bodily changes must be especially noticeable to an author who has spent a decade exploring the enigmas of death, grief, and existential crises. His latest book, The One-Eyed Man, is no exception; the main protagonist, who goes by the single Kafkaesque initial K., is grieving his wife’s untimely death. During the unfolding shock waves of grief, K. reads about Einstein’s theory of relativity, that time is merely an illusion. He no longer mourns his wife because he believes that she is not dead but absent, residing on a different plane of existence. This mental and emotional shift affects his relationship to the world around him. He soon adopts a literal-mindedness, never censoring his thoughts and seemingly chucking empathy out the window. Along his journey he encounters gun nuts, contends with the perils of grocery store marketing, and becomes a reality TV star. As in his previous work, Currie’s protagonist acts as our guide through mortal straits and as a vehicle for the author’s sardonic humor.

“Aside from my own arguably immature fixation with death, in the same way a goth teen is fixated on death,” Currie explains, “what I find interesting about death and grief from a narrative standpoint is the ways in which we carry on in the face of these things.” Currie’s novels are anything but the ruminations of pubescent mourning-wear-Nietzsche-reading-nihilists, even if his first novel was titled God is Dead. The author has taken to task many themes, but prominent among them are death and grief. His body of work explores the complexities of loss as his protagonists deal with existential crisis and dread, whether experiencing the death of a spouse, adapting to a newly godless world, or anticipating the end of the world by way of comet. Currie believes that death denial permeates throughout our culture — and though he’s quick to point out that he’s no expert, he weighs in on the topic. “We extend a tremendous amount of effort and an incredible amount of money on trying to deny death its dominion,” he states. He goes onto explain “whether it’s nutritional supplements or exercise or magic elixirs, we’re trying to stave off death with one arm and with the other arm we’re trying to hold at a distance the reality of our mortality and of those we love.”

Stories have the power to limit the self-imposed distance we create between ourselves and fears of our unraveling mortal coils. Currie contends that reading can act as an exercise in empathy. “Fiction, and particularly prose can be useful to us as human beings. Not just as entertainment but as mental and emotional exercise.” He explains, “You have to be able to effectively project yourself into somebody else’s consciousness.” And that, Currie elucidates, is empathy. In Currie’s own storytelling, the author uses humor to ease the strain of the emotional gymnastics one can experience whilst reading about the trials of his protagonists. There is a scene in The One-Eyed Man in which K. attempts to recycle his dead wife’s phone at a local electronics store. Above the bin where he can toss the device, it reads, “Please See A Sales Associate For Details.” So he does. The sales associate reassures K. that he can deposit the phone in the bin. But K., who is taking the sign literally, doesn’t grasp the concept and keeps reiterating that’s not what the sign reads. An argument about the proper disposal of the phone soon ensues. This goes back and forth as agitations flare. “Even the simple act of trying to recycle his dead wife’s phone becomes sort of a Three Stooges routine,” Currie explains. The comedic scenes in the book, Currie expounds, “allowed me to thumb my nose at grief.”

Humor has also helped Currie get through periods of his own personal experiences with grief. While writing his second novel, Everything Matters!, about a man who is born with the knowledge that a comet will strike earth and kill every living thing on it, Currie’s father was diagnosed with terminal cancer. During that difficult time, he received a call and was told that his father had developed a blood clot and might die. By the time he got to the hospital his father had recovered from the health scare. This was 2007, and the Red Sox had made it to the World Series. Both die-hard fans, Currie joked with his dad upon seeing him: “I’d really appreciate it if you did not die until after the world series.” The Red Sox won the coveted title in October and Currie’s father died shortly after, in December. “Laughter and humor have saved my life,” Currie reflects, “If I can’t laugh at something, there is a very good chance that I’m not going to make it .”

¤

Currie’s protagonists fall down the rabbit hole of grief and are summarily confronted with their own unique forms of existential crises. God is Dead is about a world where God has taken on the form of a Sudanese refugee and soon dies, her carcass being fed upon by feral dogs. This event throws the world into chaos as people question their continued existence in a godless world as they participate in suicide pacts or join child-worshipping cults, among other coping mechanisms. A pivotal scene in the novel reads like a Disney movie written by absurdist philosopher Albert Camus. One of the feral dogs who fed on God’s carcass has gained omniscient powers and the ability to communicate with humans. The dog gives voice to the dread of abandonment. He asserts that everyone is truly alone in the world, then asks: “Can you abide by this knowledge? Or will it destroy you, empty you out, make you a husk among husks?”

This sense of powerlessness is also experienced by Jr., the main character in Everything Matters!. Born with the knowledge of the end of the world, the novel opens with the question “Does Anything I Do Matter?” This leads the prognosticator of death and gloom on a path to self-destruction, abusing drugs and alcohol, as he grapples with the inevitable. Yet, this is only the beginning of Jr.’s odyssey, where he is confronted with the consequences of his actions and how it affects those he loves. The story acts as an existential road map, exploring the byways and expressways that lead to the final destinations of the varying decisions one makes when motivated either by selfishness and fear or by love and empathy.

Unlike God is Dead and Everything Matters!, where the characters confront mortality and grapple with finding a sense of meaning and purpose in the chaotic world around them head-on, the plot in The One-Eyed Man is driven by a denial of self-awareness, including a rejection of K.’s grief for his dead wife. Stemming from his belief that time is an illusion, Currie explains that it “brings his grief to an end — since time is an illusion, so is death, and there’s nothing to grieve if no one really dies.” However, as Currie elucidates, this “does nothing to salve the deep anguish over his wife’s death — but K. believes, at least for a time, that it has.” The denial leads to an inverse existential crisis as K adopts a no-filter, empathy-empty relationship to the world around him as he goes from mourning spouse, to reality star, to anti-hero. It also leads to a kind of self-imposed flagellation as he becomes a literal punching bag for the political Right and Left. He is physically assaulted by a range of aggressors, from second-amendment gun nuts to politically correct audience members who try to attack him during an appearance on a Bill Maher-esque television episode. As the story unfolds, we see that, for K., like Jr., there is catharsis in suffering. But more important, they are confronted with how their actions hurt those they love and this brings them out of their self-imposed self-harm and emotional neutering.

Currie’s protagonists are the byproducts of 21st century social and political strife, mirroring in many ways our own cultural existential crises. The One-Eyed Man, published shortly after President Trump’s inauguration, reflects our rapidly changing political landscape. K. is at times seemingly (and literally) taken hostage by our most damning characteristics of the modern age of celebrity culture, consumerism, and warring identity politics. This year has at times unleashed a shape-shifting monster rearing its ugly head and plowing into crowds of peaceful protestors. We are living in the age of celebrity presidents and white supremacists who replace traditional torches with tiki, as even they can’t escape the siren call of consumerism. Currie, who has been an outspoken critic of the president, is equally outspoken about party politics on both sides of the aisle. In An Open Letter to My Fellow Liberals Currie writes that victory is granted to “Whoever is able to see the world as it is, rather than as they would have it be.” The latter is a symptom experienced by the characters in Currie’s novels, the feeling of powerlessness is a driving force that leads the characters into denial and self-destruction. However, they are transformed by the moments that plunge them into self-doubt and fear and it is love and empathy that ultimately save them.

Reading fiction and prose are, as Currie elucidated, exercises in empathy. In his article Reading is Essential to Making Sense of Trump’s America Currie surmises the power of storytelling: “my primary motivation in reading was to find solace, not rescue. Understanding, not escape.” Currie’s novels reinforce those sentiments. The characters are in many ways the embodiment of the things we fear most: death, grief, and questioning our place and value in the world. Yet, they also have the power to provide comfort and understanding that is lacking in ever increasingly turbulent and polarizing times.