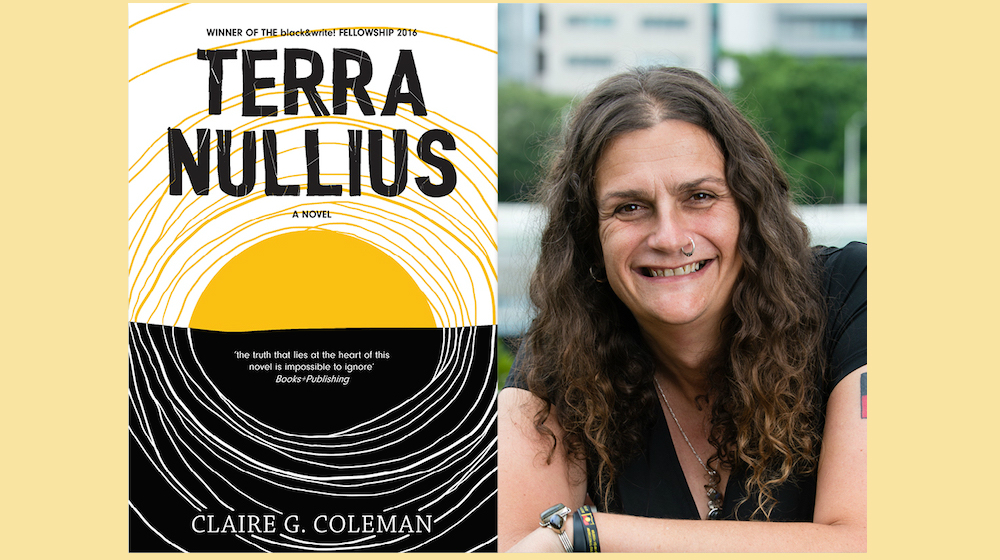

Claire G. Coleman is a Noongar writer from the south coast of Western Australia who has lived in Melbourne for most of her life. Her debut novel, Terra Nullius, won a Black & Write Indigenous Writing Fellowship before being shortlisted for the 2018 Stella Prize. It went on to win several other awards. Small Beer Press will publish Terra Nullius in North America on September 11th. We caught up to talk about the book and Claire’s practice as a whole.

¤

ROBERT WOOD: How did you come to write Terra Nullius? I am thinking, in particular, of the research you undertook from visiting historical museums in little country towns to reflecting on lived experience?

CLAIRE G. COLEMAN: In 2015, I was traveling around Australia in an old caravan when I visited the museum in the town where my Grandfather was born in our ancestral country. There, I discovered archives relating to my family that I had no idea existed. I was also invited to return for the opening of a memorial to the massacre that had occurred just outside of town.

When I returned, the massacre memorial opening changed my life. I was immediately aware that massacres are part of the experience of every Indigenous Australian family. My family was no exception. Since then, I discovered that the evidence of massacres is all around us in Australia. To research the history of Australia all that is needed is open eyes, anyone paying attention will see it all, it’s in every information center in every town, on plaques on statues, everywhere.

I was traveling anyway so all I had to do was look everywhere, see what I could.

The other thing I discovered, and this was important, is that most non-Indigenous Australians have no idea of the true history of the country. Almost everybody I spoke to taught me something about the ignorance this country maintains towards our own history. To this day, I cannot understand how this ignorance is maintained.

This is where the book becomes important, as a way to change that ignorance. Tell us about Terra Nullius — what is the story and what can readers expect from the writing style?

I have been told my prose is poetic, or that the language I use to write prose has a lot of poetry in it. This is not a conscious choice, it is merely the way I want the story to sound. I was a writer of poetry before I started writing Terra Nullius. I was struck how the rhythm and sound of words, even when sounded out only inside the head, can add a sort of impressionistic meaning to the work.

I love work where the language itself adds to the feeling of the story, where language is used for tone, for emotional content. Therefore, when it came to Terra Nullius I attempted to give the work that sort of effect, that sort of feeling. I have been told it worked although it is impossible for me, being so close to the work, to be sure.

One particular part of my style that I was conscious of, that readers might find interesting, is that I have used the description of environment to strongly imply a lot about the personality of the character whose point of view the reader is sharing at any time. There are several points of view in the novel and all of them see the world very differently.

Seeing the world differently is a really important part of the work, and at the Perth Writers Festival you spoke of “sneakiness” and choosing the novel as a way to get a message across. This was partly a response to a reluctant, even stubborn white audience who don’t want to know about Indigenous Australia. These are people who maintain that ignorance. Can you speak about this novel as a vehicle for social change?

I created Terra Nullius as a vehicle for social change. I had been struck by the ignorance regarding the experience of Indigenous Australians since the invasion of this continent and I wanted to find a way to change how the invasion was viewed. I believe that many of our problems in Australia are caused by the foundation myth of this nation, by the belief that the English arrived on virgin soil, on unoccupied land, and simply moved in.

This foundation myth is obviously false and has, of course, been overturned by the Mabo Decision. Yet history and the minds of non-Indigenous people treat the subject quite differently. Although it is obvious that the British invaded this continent and massacred the First Nations people, it’s common for non-Indigenous people to think and say “we were here first” when faced with other people wanting to settle in this country.

I had sought a way to teach people how it must have felt to have your land stolen, to be a second-class citizen on what was essentially your sovereign land. Terra Nullius was the tool I came up with to attempt to change the dialogue. Once it’s understood by all Australians that the foundation myth of this nation is built on lies, social justice for the First People is sure to follow.

That message, that ability to tell the truth gives the book a lot of power. It also ties in with your use of metaphor and directness. Terra Nullius as a whole is metaphoric, a work of imagination, but it is also direct in its language and its truthfulness about colonization. This is even apparent in the title of the work. Can you speak to us about the combination of metaphor and direct language in your personal style? And in that way, why did you choose this way of narrating it, this “voice”?

I had a direct message to deliver, had something to say that was painful for me and could be painful for others. The history of Australia is not beautiful. The history of Australia is steeped blood. It was important to use directness to tackle the history of Australia. To not be vivid and direct in my unpacking of the history would do that history an injustice.

On the other hand, the metaphors, and the big metaphor that I don’t talk about, are necessary for the work to have the impact I am told it has. Just being direct would not have achieved what I was trying to achieve.

In Terra Nullius the directness and the metaphor, the truth and the fiction work together, remove any one of them and the work does not achieve what I set out to do. The truth and directness sets up the metaphor, builds the foundation on which it stood.

It is a strong foundation and there is also a propulsive quality to the book. It makes you want to read on and there is lots of action, especially running. How do you build narrative momentum? What does it mean to balance writing a page-turner with writing a book of ideas?

I was completely aware when writing Terra Nullius that it would not work, would not create the attitudinal change I was looking to enact, if people stopped reading. Therefore, it needed, from the very beginning, to have pace. I created a narrative based around frantic panicked movement to hold the attention of the reader. Part of the way I achieved that was by fast cutting between characters.

Much of the effectiveness of the pace was not completed in the first draft but was created in the multiple rounds of editing. Having completed a novel, I am now a firm believer in editing as part of the creative process of writing. Where the pace was not working I tweaked it.

On the other hand, I was also simply writing the novel I wanted to read. If I was not held to the story, if I got bored with it, I decided it was boring and fixed it.

That gives us a great understanding of the book’s origin, its purpose, role and style. But, what comes after Terra Nullius? What is the future work you would like to do as a writer?

Since Terra Nullius, between the end of editing and now, I have written another novel that is slated for publication in the second half of 2019. It is a different story but I have brought to it many of the elements I loved in Terra Nullius.

I am also working on a third novel, again tackling social justice issues, just in a different way. This is in addition to irregular commissions for opinion pieces, essays and short stories. I have much in the pipeline.