Nathalie Léger’s novel Exposition, released in September 2020 by Dorothy, a publishing project, and Les Fugitives (December 2019), is part of a genre-blending and -defying triptych that sets stories of women artists against the narrator’s attempts to understand herself and her own past. In Exposition, the narrator — like Léger herself, a writer, archivist, and curator — is assembling an exhibition when she becomes fascinated by photographs of the Countess of Castiglione, a famous (one might also say infamous) 19th-century Parisian beauty and likely the most photographed person of her age. Castiglione’s portraits lead the narrator into a labyrinth of philosophical, political, and personal questions about art, the body, and a woman’s relationship to her own image, but also to a reevaluation of a key event in her own childhood. Léger’s erudite and intensely engaging prose has been rendered brilliantly into English by Amanda DeMarco, who manages to convey both its clarity and its ambiguity.

Amanda DeMarco is an American writer and translator based in Berlin, translating from French and German. Our conversation was conducted via email and has been lightly edited.

¤

MADELEINE LARUE: Exposition is anchored in the description of dozens of works of art, mainly photographs of the Countess of Castiglione. Some of these images are fairly well known, but most are not, and the narrator’s descriptions of them are sometimes tendentious — she calls them pictures of “self-defeat” and “desolation.” What effect does this reliance on ekphrasis have on the novel, and did you find that it influenced your approach to the translation? I’m curious as to whether you sought out some of these lesser-known photographs, for instance; did you want to see those portraits for yourself, or did you prefer to experience them only through Léger’s descriptions, as many readers would?

AMANDA DEMARCO: The many descriptions of art in this book add a richness to it. Sometimes they’re shorthand for something, sometimes they’re a detour. Sometimes they’re the main event, and sometimes they’re a sly trick for diverting your attention to another topic entirely. Léger is an erudite person who uses referentiality in compelling ways.

Yes, I absolutely sought out the images Léger was describing. First and foremost, it’s a practical consideration. Many of her descriptions, while also being subjective, provide objective information about the layout of the image, and to make sure the details are right — the foot of a little iron table edging into a portrait, a swan-feather cape sliding down Castiglione’s shoulders as she gazes at herself in a mirror — I needed to see the image. Languages don’t correspond perfectly, there’s slippage in what they express. I needed to make sure that my translation was true to the original text, but also to the thing it purported to describe.

Then there’s the consideration of mood. There were probably times when the images swayed my word choices with their emotional content. What is “desolation” or “self-defeat”? These descriptions may be tendentious, but they do reflect something inherent in the image — if nothing more than the tightly drawn line of Castiglione’s mouth. It’s not as direct as describing a table leg, but certain moods expressed in these images are there for anyone to see.

And finally, there is the matter of curiosity. Translation is an activity that involves fascination, obsession even. You get into the material. Even if I had been locked in a cell and forced to produce the translation without looking anything up, when I got out, I would have gone and found the images anyway, to satisfy my own curiosity. Exposition is a book with many hooks in the world, and the world is simply a very interesting place. But I also believe that you could read this book without looking up a single image and that the book itself would function just the same. You would end up creating a Castiglione of the mind, and that’s interesting too.

Let’s talk more about that Castiglione of the mind, and obsession! The narrator becomes obsessed by Castiglione in the course of a curatorial project, and a lot of the novel is an attempt to tell the story of this woman whose image is abundant but whose essence remains elusive. For all her hundreds of photographs, Castiglione is opaque, almost a cipher — and this is obviously part of her appeal. Does this kind of obsession resonate with you as a translator and writer? And how do you navigate and see yourself fitting into this chain of women telling other women’s stories?

Yes and no, it does and doesn’t resonate with me. Though I spent a great deal of time looking at photographs of Castiglione, she never became my obsession. But that’s the nature of obsession, it’s idiosyncratic — the overwhelming force of the appeal probably isn’t located in the object, but rather in the way it connects to a particular person’s frame of mind. I am, however, extremely interested in particular people’s frames of mind. (This is what is otherwise known as being a passionate reader.) So, while it would never have occurred to me to write a book about Castiglione, I very much enjoyed translating one.

Yes, it meant a lot to me to translate a book by a woman talking about other women, in particular because, although I have been translating for many years, this was the first time I had the opportunity to translate a book by a woman. We know that women tend to be translated less than men, and in my case the problem is compounded by the fact that I often translate philosophy, a field in which women are underrepresented. So this was a wonderful way to finally start. I don’t believe in some sort of essential difference between male and female voices, but Exposition is a story that I think could only be written by a woman.

In a recent interview, you asked Léger why she was compelled by the theme of failure. She replied that she “prefer[red] to speak of defeat rather than failure.” I’m intrigued by that distinction, and wondering if you feel it has a gendered aspect? Léger herself cites a lineage of male writers who dwell on failure, from Homer to Beckett, but the trilogy that Exposition is part of deals with women whose defeats are largely brought about by men, or at least by patriarchy.

I don’t think it’s inherently gendered — women can certainly fail, as well as be defeated — but I think it’s gendered in terms of the pattern that Léger chose to highlight in the triptych of books that includes Exposition. Castiglione, Barbara Loden, and Pippa Bacca were all ambitious women in their various ways, but none of them was able to control her destiny. All of them were living and working within a system that was inimical to their success, self-respect, or even survival. And this is what makes it defeat rather than failure. And yes, patriarchy is precisely the word for the system. I agree that defeat-versus-failure is an interesting distinction. I think Léger is able to successfully write such wild, genre-bending books because she has a mind that recognizes such distinctions and makes them visible. The thinking involved in an undertaking like that has to be very sharp. It also helps that these women weren’t entirely defeated. Pieces of their work have made their way to us (Castiglione’s portraits, Loden’s film Wanda, Bacca’s performance art), and these works give us insight into their vision. Then Léger takes this work and presents it to us in her particular way.

How did you come to this particular book?

Like many American readers, I first read Léger’s Suite for Barbara Loden. It fascinated me enough at first glance that I wrote a review of it, though I didn’t know then that I would translate anything by her. All three of the books in the “triptych,” which also includes The White Dress, use the formal strategy of telling the story of a woman who is too close to the author (her mother) through the story of a woman who is more distant, and yes, I found this tactic absolutely gripping.

I’m glad you brought up the narrator’s mother. She’s the third figure in the book’s constellation of women, but we learn very little about her: just a few tantalizing facts, like that she was abandoned by the narrator’s father for another woman. In this respect, Léger reminds me of other French writers — Barthes, Cixous, etc. — who, it seems, could only approach their mothers obliquely in their work. Léger writes that “Like death (and perhaps one or two other things), the subject is simply the name for what cannot be spoken.” (Why) Are mothers one of these things?

I think mothers are certainly one of those things that “cannot be spoken,” one of those subjects that are very difficult to write about. It could be described as a problem of balance: they are too close to us, and yet also often too distant. Yes, like Léger, Cixous is certainly someone whose literary career has spiraled around her mother (a spiral being a shape that is attracted to and yet avoids a point). Léger writes about Barthes and his mother, retelling how he’s moved by finding a childhood photograph of her. Photography really resounds with the dilemma of the child’s relationship to its mother: it is a medium that gives the illusion of absolute directness and immediacy, while requiring a complex device be placed between the photographer and her subject. An ideal medium for difficult but irresistible subjects.

I love the image of the spiral — and it seems to apply as much to the structure of Léger’s sentences as it does to her treatment of her subject. I admit that many books written in fragments like this feel a bit lazy to me, but Léger handles the form masterfully. She covers so much ground, and yet the pace never slackens; her sentences are often very dense, and yet they have an incredible momentum. You mentioned that you’re an experienced translator of philosophy, another genre known for its demanding sentences. How did translating Exposition compare to other experiences you’ve had, and what made it distinctive?

Fragmentary, wandering texts are some of the most difficult to write well, I think, and often texts that seem the most “natural” are actually carefully composed. Léger is certainly a master of this form. And I think that it’s precisely because they seem natural at first glance that they’re so difficult to translate. Their density has to move at a fast clip and they must sometimes sound offhand. Philosophy may be dense (though it isn’t always), but we expect the voice of the philosopher to be stately and meticulous (though it isn’t always), and so there is a certain harmony of content and form there — “offhand” is not a word that would come to mind. I also found the language of Exposition to be highly idiosyncratic. Now, all writers do this to a certain extent, they use certain words in a way that is different from the way most people use the same words. But I found Exposition to be particularly full of these “trap doors”: words or phrases that, because they’re integrated into a well-built sentence, seem perfectly unremarkable at first glance. But if you read the sentence carefully, you find that a particular word is a hatch that leads someplace unexpected. As the translator, you go down the hatch.

Can you give us an example? I’d love to hear about how you discovered and worked through one of these “trap doors.”

I remember absolutely wrestling with the sentence “Just beyond this audacious body, this impetuous presence, whose timid body is it advancing unwillingly into the light, what dust, what fear, what regret?” (In the original: Aux abords de ce corps audacieux, de cette présence impétueuse, de quel corps timide s’avançant contre son gré dans la lumière, de quelle poussière, de quelle crainte, de quel regret?) In this line, Léger is addressing her own question, “What am I trying to talk about?” In other words, it gets at the heart of the book’s dilemma, the difficulty of its subject. The way the sentence falls apart, both grammatically and in terms of substance, makes it difficult and that’s the point.

The translator’s instinct is to “pin down” the meaning, “get it right,” but this is a sentence that is purposefully wrong and should not be pinned down. Whose body is she talking about? Certainly Castiglione’s, but in another sense her mother’s. This is perhaps why it is paradoxically both “audacious” and “timid.” And she doesn’t answer her own question in a “correct” way by saying “I am trying to talk about something beyond this audacious body.” No, she begins simply with “beyond,” as if the answer were more of a tenuous and perhaps otherworldly region where one could begin searching for what she’s trying to talk about. The content of the sentence itself becomes ever more ethereal as it progresses: from body to dust to fear/regret. From any normal standpoint, it is a sentence that abides by neither grammar nor logic, an idiosyncratic sentence.

Very idiosyncratic! And perfectly representative of Léger’s ability to keep us with her even as she defies the conventions of form. How closely did the two of you work together during the translation? Were there any particular sentences or passages that you felt were true co-efforts?

When I translate a book, I complete a draft on my own before sending questions to the author. The reason for this is practical: with enough time and thought, I often answer my own questions. As the text develops, possibilities eliminate themselves for reasons of voice. When the draft is finished, I’m left with the true mysteries, which I send to the author. But of course, they can’t solve your problems for you. They can elucidate from their side, but I’m still the one who finds the English for it. Add to this the work of good editors, who shouldn’t go unmentioned.

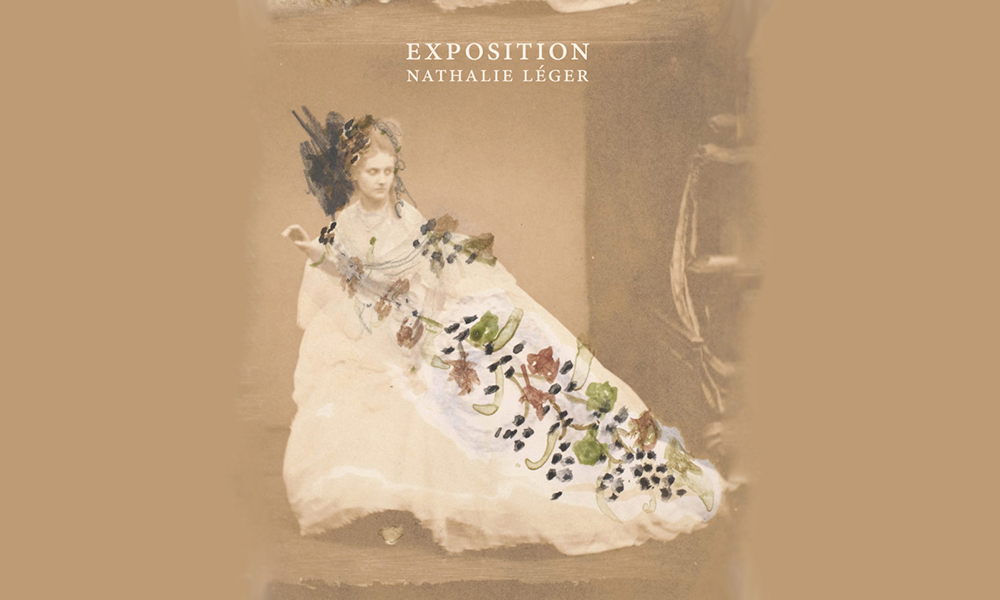

Top Image: Cover of Exposition by Nathalie Léger, translated by Amanda DeMarco, Dorothy, a publishing project, September 2020.