Like the apocryphal frogs splashing in their warming water until the inevitable end, the characters in Vanessa Hua’s debut, Deceit and Other Possibilities, get into their predicaments first slowly, then very fast. Driven into impossible circumstances by hubris or ambition, desperation pushes them to try any exit. Though their troubles are specific, the unsettling sense of scaling walls too smooth for traction as the water starts to bubble is painfully familiar. That futility — the gaps between what Hua’s characters want and what they get to have — makes the reader root for the break-ins, gunshots, and fires that are their last resorts. It’s easy to recognize the desires that drive them, so even extreme measures feel like reasonable escalation when nothing else works.

There’s little in the way of happy endings. But there is satisfaction in the utility of deceit and destruction, in the characters’ recklessly reclaimed ability to turn up the heat themselves — even if it means they’ll burn.

OLGA KREIMER: You spent many years working on these stories. What is it like to look back at your career through this collection?

VANESSA HUA: “The Responsibility of Deceit” was my first published short story, written after I’d taken a few years off from fiction to focus on journalism. I was fearful that I’d forgotten how. After taking a couple workshops, joining a writing group, and submitting to journals, I remember getting the email notifying me that I’d won the Cream City Review’s fiction contest. I stood up at my computer in the newsroom and shrieked with joy. I look back upon that story with deep affection, the first sign that what I was attempting on weekends and weeknights might get published — that I wasn’t shouting into the void.

With any book-length work that spans years, I believe you’re a different writer at the end than you were at the beginning. When I assembled the stories into a collection, I revised it from start to finish, and did so again when it won the Willow Books contest, cutting out repetition and striving for coherency. The stories aren’t arranged chronologically, and I’m curious to see if readers can tell which ones were written earlier or later.

How do you separate your journalism brain from your fiction brain? Do you have distinctions in the times or spaces in which you write each, or rituals around them?

Both journalism and fiction writing can be all-consuming, posing dilemmas that distract you when you’re with your friends and family, that make you bolt upright at 2am when you figure out a solution — or that you’ve made a mistake.

In journalism, I learned how to write quickly on deadline, how to organize and compose a story during the interview and on the drive back to the office. I’m used to getting feedback, I’ve been disciplined to write daily, and I feel free to follow my curiosity — all of which helps me write fiction.

Fiction can feel much more wide open and thus more daunting — a blank page on the computer as big as the world. I often do research too, through interviews, reading books, or searching on the internet, but in contrast to journalism, the gaps are the most potent places for inspiration. What you don’t know — what no one knows — becomes the jumping off point for a story.

When possible, I work fiction in my “hours of power” — in the mornings, when my concentration and my thinking is at its sharpest. Late afternoon, when the babysitter is about to leave, I get a burst of inspiration and productivity. I’ve been trained to work against the clock.

What’s been the most fun or unusual piece of research you had to do for a fiction piece?

I am fortunate — my research is often fun and unusual, satisfying my curiosity in the name of work. Trying to get a better sense of evangelical culture, I visited Korean mega-churches and a seminary undercover, posing as a prospective student. To learn more about Chinese peasants, I traveled through the countryside. I chatted with villagers about their life under Chairman Mao, about their daily routines and what they ate. How strange I must have seemed! Imagine a Chinese writer stopping at farm-stands in the Midwest and asking, “Could you tell me what you had for breakfast?”

I’ve hit up my doctor friend with questions such as “What does a gunshot wound smell like?” or “What happens if you fumble with an IV line?” and sought out my lawyer friends asking about immigration law. My Google searches on any given day would alarm law enforcement: how to make bombs out of gasoline, what clogs an airplane toilet, what’s the smell of burned flesh.

Most of your stories circle around the experience of being between cultures in some way. Can you tell me about your own experience with that?

I am the daughter of Chinese immigrants. From early on, I understood that my family wasn’t like the other ones in my neighborhood and that I’d have to learn many aspects of American culture on my own and interpret for my parents — even though they could speak English, they weren’t raised here and didn’t get all the nuances of suburban culture. One Halloween, after our house was festooned with toilet-paper, my mother drove us while we threw eggs out the window at each neighbor’s driveway. That was what the custom, my younger brother and I explained. That was how you got revenge.

You’ve mentioned how much having kids has opened your world. You hear that a lot from parents. Can you tell, re-reading your stories, which side of the divide they fall on?

After I became pregnant, after I gave birth, after I nursed, I felt as if I’d stepped through a threshold, into another world, of emotion, of ideas, of experience that I hadn’t known and was eager to explore in my writing. Motherhood has expanded my view, opened my heart and my fiction in ways I didn’t foresee. Not only in terms of new experiences (breastfeeding, bodily fluids, sleep deprivation), new people (playgroup mothers) and new places (every kid-friendly locale in a wide radius) — but also a new approach the world. I remember when the twins experienced rain falling for the first time, the way they turned up their faces and held up their hands, puzzled and in awe. I felt it too.

As morbid as it might sound, I think about death more often. I’ve joined the Sandwich Generation, squeezed by the demands of caring for young children and an elderly parent. Any time I read an obituary, I check if the deceased is older, the same age, or younger than my mother and in-laws. More and more, I hear about friends-of-friends who are passing away, struck down by cancer or an accident. I read every news clip about the untimely deaths of babies and toddlers — clips I would have skipped past before having children. Mortality is in the foreground when I consider characters, their concerns and their stakes.

I wrote most of the stories in the collection before I had children. Looking over it now, I see that where I explore family dynamics, it’s mostly from the perspective of a child or adult-child, figuring out their parents. That was what I was familiar with and what compelled me at the time. In my forthcoming novel, A River of Stars, a Chinese factory clerk travels to America to deliver her baby, giving the child U.S. citizenship. I started writing it when I was pregnant, and the novel draws more heavily upon my experiences as a mother.

Do you see writing as a career for solitary people? What makes writing feel less lonely for you? What make it feel more lonely?

When I worked full-time as a journalist, I was out in the world interviewing sources or gossiping and collaborating with newsroom colleagues. As a fiction writer, I’m by myself much more often. I have to be, to complete a book-length project. I’ve become solitary by choice — or is it out of necessity? — and not by nature. I love organizing gatherings and connecting people.

I suppose I feel lonely when I’m struggling with something in my work, and I wish I had co-workers to whom I could vent or with whom I could toss around ideas. I have a virtual water cooler buddy, another author who works at home, who I talk to nearly every day. I also belong to the Writers’ Grotto in San Francisco, where I’ve found much support, advice and encouragement.

I feel lonely when I shut myself away from my family. At times, I’ll be working on an essay about my twins and I can hear them through the walls, playing in the room next door. They pound on the door to my office, and I don’t let them in. That’s the writer’s paradox, isn’t it? To turn your scrutiny on a loved one, you must stand apart. Your clearest thinking may come when you are at a geographical and temporal remove.

There are a million different prescriptions for how to become a writer. Stephen King’s ten pages, or Anne Lamott’s one bird at a time, or even Capote’s cocktails. What do you consider the one most important piece? (With the acknowledgment, of course, that it takes a lot of pieces.)

I’ve tried different prescriptions, which work with varying degrees of success depending on the state of my life and what I’m working on.

If I’m feeling tired or less than inspired, I may work on pitches or send out queries. To immerse myself in a long manuscript, I run it through a text-to-voice app on my phone and listen while I go running; I’m trying to make the most of limited time, exercise plus revision! I’ll also read it aloud to myself from my tablet, which helps me notice what I have missed looking at the computer screen.

When I’m deep in the first draft, I try to backwards engineer what I’ll need to do in the next three to six months to get through it. That is, how many pages I have left to write, at a pace of how many per week, per day — and I can wrap my head around the work ahead.

I take such measures because of the maxim I follow above all: no one will care as much as you do. Not your partner, not your editor, not your family, not your friends, not fellow writers. You must do as much as you can to write the best book possible, and to work at getting it out in the world.

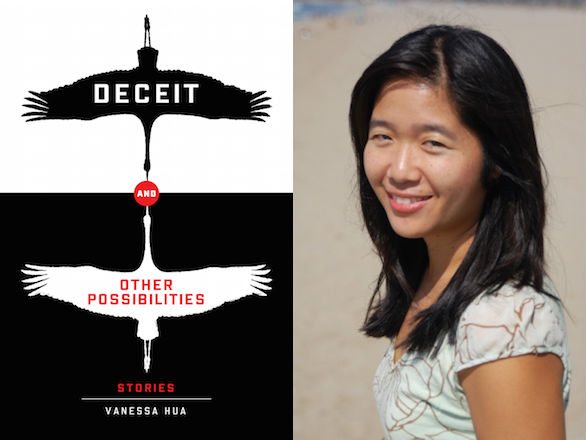

One of Vanessa Hua’s stories from Deceit and Other Possibilities was featured on LARB Lit, click here to read it.