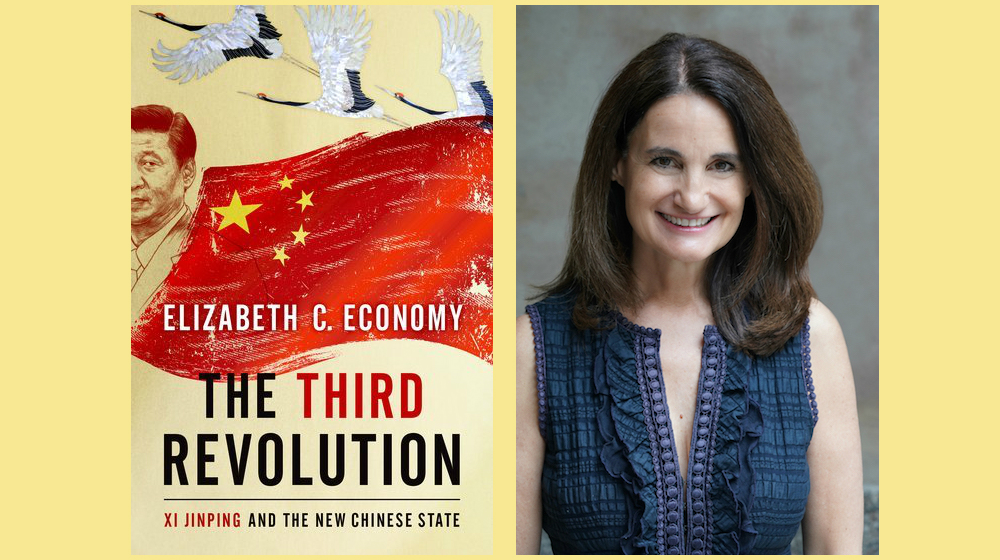

How has China fared recently on reaching its own official goals (for instance in terms of economic growth, governmental accountability, military power)? How to assess China’s claims of having become a responsible international leader (particularly within the context of dysfunctional American foreign policy under Donald Trump)? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Elizabeth C. Economy. This present conversation focuses on Economy’s book The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State. Economy is the C. V. Starr senior fellow and director for Asia studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, and a distinguished visiting fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution. Her previous books include (with Michael Levi) By All Means Necessary: How China’s Resource Quest is Changing the World, and The River Runs Black: The Environmental Challenge to China’s Future. Politico Magazine recently named Economy one of the “10 Names that Matter on China Policy.” She frequently appears on national television and radio, and consults for US government agencies and companies.

¤

ANDY FITCH: I appreciate this book’s attempts to measure what a Xi Jinping-led Chinese Communist Party seeks to accomplish against what it does accomplish. So could you first outline basic elements of what The Third Revolution might consider Xi’s Chinese Dream: in terms of GDP growth, baseline social welfare, globally projected military capacity, and long-term domestic stability for a CCP-led “socialism with Chinese characteristics”? And how might these specific details of Xi’s Chinese Dream compare to other potentially viable models for what a Chinese Dream could look like?

ELIZABETH ECONOMY: At the heart of Xi’s Chinese Dream there is the idea that China will reclaim its greatness, and maybe its centrality on the global stage. And how Xi intends to go about this distinguishes his China from “Chinas” that have come before, and from previous leaders’ conceptions of Chinese greatness. I do want to note that preceding leaders, from Deng Xiaoping on, have talked about revitalizing China and reestablishing its greatness. So in that way, Xi’s Chinese Dream offers nothing new. But Xi has set out different targets and objectives. He has certainly prioritized a robust Communist Party at the forefront of the political system. And since he first came to power, Xi has emphasized addressing corruption in the Party — because the Party had become little more than a stepping stone for officials’ personal, political, and economic advancement.

Xi also wants a People’s Liberation Army that is capable of fighting and winning wars. Of course this army has had no actual combat experience since the failed invasion of Vietnam in 1979 — which is still not really acknowledged. So Xi has this untested military, and doesn’t necessarily hope to test it in the near future. But he does aim to ensure, in terms of the military’s organization and capabilities, and the sophistication of its weaponry, that it is top-flight. Xi believes that the PLA needs the capacity to protect not only the Chinese homeland but also China’s assets abroad, whether its people, transmissions lines, supply chains, or commercial routes.

On the economic front, Xi wants Chinese incomes to double between 2010 and 2020. He wants China to have fully modernized its economy by 2049. Basically, he wants China to compete not just as a global manufacturing center, but as a global innovation center rivaling the United States, Germany, and Japan. Beyond raising Chinese income levels and eradicating the poverty that still remains in his country, Xi seems focused on developing this competitive, advanced economy where China can stand toe-to-toe with anybody in the world.

Of course my first question focused from the start on one particular individual within a country of 1.4 billion people, and amid a governing structure that at times has produced more diffusive Party leadership than any single-minded focus on a given CCP General Secretary might suggest. How much does a Xi-led government differ from recent predecessors in terms of this one figure’s consolidation of power, the scope of his personal vision and / or policy initiatives, the degree of commitment he (and potentially his party) brings to these promised initiatives, and the national resources / capacities he can draw upon?

I do consider Xi a transformative leader. I think of what this book terms “the third revolution” really as upending Deng’s second revolution. So let me quickly sketch four important ways in which Xi’s revolution marks a departure from the Deng model of reform and opening up.

First, as you suggested, Xi has consolidated personal political power. Xi is not one among many within the Politburo Standing Committee. Xi is first. He sits at the top of the most important committees overseeing broad swaths of Chinese policy. He has essentially abolished the two-term limit for the presidency — a shift which went against the grain of many, many retired officials and elites within the Communist Party, who took pride in the Deng-era institutionalization of succession that this two-term limit represented. In terms of the expanding cult of personality around Xi, his willingness to allow the Chinese people to write songs about him, to mount huge posters of him, to revise recent Chinese historical narratives to stress his role (or even to stress his father’s role) while downplaying other Chinese leaders: again in all of these ways, you see a big shift from the Deng era’s emphasis on collective leadership.

Second, we’ve seen an increased penetration of the Party into Chinese life (both political and economic arenas), whereas Deng sought to withdraw the Party to some extent, to deconstruct the state-owned-enterprise system, and to enhance the role of the market. Xi’s Communist Party is playing a much more intrusive role on the Internet, by constructing the social-credit system, and by expanding a surveillance state more into something like a police state. These shifts represent an increase of Communist Party presence in commercial firms and nongovernmental organizations — basically blurring lines between private and public in ways we haven’t seen since the Mao Zedong era.

A third significant shift has been Xi’s increasing control over what comes into China from the outside world. Xi has launched a pretty significant campaign to root out Western values and ideas, whereas Deng always believed that China had a lot to learn from the outside world, and a lot to gain by attracting foreign capital. Xi perceives foreign ideas and foreign competition as a threat, not as something that could potentially make China stronger. So we’ve seen, for example, a very precipitous drop in the number of foreign NGOs operating in China, from somewhere over 7,000 to fewer than 400 in 2017.

And finally, along the way we’ve seen a simultaneous shift away from Deng’s much more low-profile foreign policy, to something far more ambitious and expansive.

You’ve already hinted at Xi’s contradictory-seeming attempts to straddle legacies of two quite divergent CCP policy approaches and leadership styles, as represented by his two most prominent predecessors, Mao and Deng. Here could you continue to sketch how Xi has pivoted away from his more recent predecessor Deng’s model of promoting economic growth and manageable institutional reform by taking incremental steps towards commercial / social / political liberalization — with Xi instead seeking to pursue further growth, further reform, even while reversing such liberalizing trends?

Watching Xi draw on these two legacies over the past six years has been fascinating. And frankly, when it comes to the overall political system, Xi seems much more Maoist in his approach — in terms of assuming his own core centrality within a China governed by a single authoritarian leader (not by some collective leadership), and again in terms of the Party penetrating all aspects of society, the unwillingness to consider divergent views, and the active campaign to paint the West as an enemy or threat. Xi also comes across as quite Maoist in how he represents himself as bypassing the untrustworthy intellectuals and elite to engage directly with the masses. Xi has skillfully invoked this notion of “the mass line,” and of the Party learning from the people. The Party might penetrate and control the people, but it also has to respond to the needs of the people. So Party committees today have to recite Xi dogma, invoking Marxist-Leninist ideals, even when those ideals don’t hold much sway within contemporary China, aside from helping to support a rejuvenated cult of personality.

In terms of foreign-policy comparisons between Xi and Mao, of course during the Cultural Revolution there were elements of autocracy in China. But Mao also (to a varying extent) promulgated revolution abroad, and supported Communist parties in Southeast Asia and Africa. And now to some degree, for the first time since Mao, we see a Chinese leader suggesting that China has a political or a developmental model that others could learn from. So in that sense, especially over the last year or two, I’d actually point to Xi exporting elements (albeit not the entirety) of a Chinese model in ways that didn’t happen during the Deng era. This has come about as a function of Xi’s belief that China has cultivated a successful form of development. It also has come about as authoritarian regimes have gained strength around the world, further assisting China’s ascendance on the global stage. In terms of, say, United Nations support for human-rights issues, or global conversations about Internet sovereignty, you now see more countries adopting domestic policies somewhat similar to China’s, and supporting Chinese efforts to re-shape norms and institutions around its own values. I would also consider this a Maoist strand of the Xi period.

Similarly, compared to the Deng period’s emphasis on the market playing a decisive role in the allocation of capital and resources, the Xi era has rehabilitated a more statist approach to the economy. I think this all reflects Xi’s personal presence (as someone afraid to let go of the levers of control) both politically and economically. By moving to place Party committees not just in state-owned enterprises but even in private and joint ventures, Xi has basically sought to make all of these enterprises agents of the Chinese state.

Nonetheless, we do see that with mounting foreign pressure, China has drafted some new laws designed to open markets to greater foreign competition. How this all actually plays out remains to be seen. But China still does have its share of economic reformers arguing that if China does not continue to open up, and cannot deliver on promises of further economic reform, then the economy basically will stagnate — that the country can’t just continue with this same pattern of low-cost exports and investment-led growth. So Xi also faces domestic pressure to adopt a more market-oriented approach, though that goes against his natural inclination. This means reducing the role of state-owned enterprises to free up capital for the more innovative, efficient, and profitable private sector, opening the door more widely to foreign competition, and moving away from overseas investment projects that serve political rather than economic purposes.

Returning then to broader global developments that certainly might seem contradictory from an American perspective, China, an illiberal state, seeks to project itself (particularly amid a global vacuum left by dysfunctional American foreign policy under Donald Trump) as a pillar of the prevailing (at least until recently) liberal international order. China presents itself as a champion of global trade while obstructing the free flow of information, capital, and material goods into its own society. Xi’s China claims to responsibly pursue a “shared future for mankind” even while undermining existing international regimes on environmental protections, human rights, bio-ethics. So what would be the most proactive steps that Xi’s CCP could take in the near future to convince the US and its allies that China’s pursuit of economic and political self-interest need not prove irreconcilable with robust pro-liberalization international norms? And / or what are some topics on which you would most willingly hear out Chinese claims that what looks to us like the undermining of a beneficent liberal order actually represents a necessary recalibration from post-colonial or Cold War approaches?

First, for my own basic view, I’d say that China poses a significant challenge to the values of the liberal international order (in terms of market democracies, human rights, freedom of navigation, and free trade). So then what would it take for Xi to stand up at Davos and proclaim China a champion of globalization and a leader on climate change, and for us to believe that he really means it? Here I’d note that while much of the media and many international figures at first seemed to accept some of Xi’s rhetoric blindly, increasingly, as they observe China’s global impact, they have changed their tone. They’ve started questioning this gap between the rhetoric and the reality. Whether on a topic like Internet sovereignty or the protection of human rights, I think China’s approach and actions now trouble many people throughout the world. I sense much more resistance to any default assumption or acceptance of China becoming a global hegemon, and a model capable of replacing the United States. I think many countries feel that China is actively trying to undermine their own democracies and norms and values, for example in Australia. Countries are taking this as yet another signal that Chinese institutions operate in ways that people (both at home and abroad) cannot and should not trust.

If you did want to point to China stepping up to the plate and becoming a responsible global player, then maybe you could point to policies like the Belt and Road Initiative, which certainly has self-interested elements, but which also could potentially contribute to constructive developments in some of the least developed countries, and could provide a positive force for global growth overall. Though here again we see a lot of concern about the way that China does business, about the lack of transparency in Chinese lending practices, about China’s failure to undertake social- and environmental-impact assessments for some of these large infrastructure projects, about China often not using local labor (with close to 90% of Xi’s projects actually completed by Chinese construction firms), and of course about corrosive debt and corrupt dealings at the top governmental levels in any number of countries. So while the ideas behind the Belt and Road Initiative in its broadest conception still could find themselves received positively around the world, as China moves forward with this initiative, we have seen many, many problems emerge.

One area where China has developed interesting ideas (again certainly self-serving, but perhaps worth exploring further) might be around this principle of a “community of shared destiny.” When you follow Xi’s public statements, or when you travel to China and talk with foreign-policy officials and analysts, this idea comes up repeatedly. It sounds very benign. But at its heart it translates into the end of the US-led alliance system. Basically, China would characterize this US-led alliance system as anachronistic, as a relic of the Cold War, as something we no longer need. Plus, China never got to play a substantial part in those alliances. So now we really need a community of shared destiny (which again sounds fair and reasonable, right?). So would it be worth it for the United States and China (and all other countries in the world, frankly) to sit down and think through what a new security architecture might look like? Maybe. But again, until China demonstrates its willingness to uphold certain fundamental principles and rights (even on agreements it already has joined, such as the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea, or in relation to the World Trade Organization), I think many countries will feel quite reluctant to work with China on redesigning international institutions or drafting new rules of the road — because these countries don’t see China upholding the principles that have in fact contributed to peace, stability, and prosperity for the past 70 years.

Here still in terms of this relation between rhetoric and reality, but now again on a more domestic scale, I also found fascinating Xi and the Chinese Communist Party’s need to negotiate a complex historical dynamic in which a “rising” or “resurgent” China sometimes self-consciously links itself to, and sometimes still defines itself by departing from, past imperial precedent — say, for instance, as the Party reinvigorates the state’s traditional role in managing the economy, censoring social dissension, projecting its propaganda megaphone and its regional power. And here, for one concrete point of focus, could we look at how Xi’s campaign to reform systemically corrupt and / or ineffectual governance, at both national and local levels, itself echoes (even as it claims to critique) inherited administrative precedent? Here could you sketch how Xi’s own personal background has led to this present call for a new “revolution”? Could you give some sense of the scale of Xi’s anticorruption initiative, and how this degree of commitment might differ from predecessors’ rhetoric-heavy anti-corruption campaigns? And given that Xi’s consolidation of power only can come by taking power away from other institutions and offices and individuals, what sorts of pushback do you see, or have to assume, or anticipate against Xi’s anti-corruption messaging, both while he remains in office and if / when he steps down?

When Xi came to power his very first speech talked about how corruption, if not addressed, could be the death of the Chinese Communist Party, and even the death of the Chinese state. People might often note that Xi first served as Party secretary or governor in a number of economically successful provinces, like Zhejiang or Fujian. But the truth is that Xi basically just rode a broader national wave of economic success. He didn’t contribute anything particularly new to that. He didn’t distinguish himself by undertaking pathbreaking economic reforms. He didn’t bring any such reforms to a halt, but he certainly didn’t create or initiate them either.

But throughout his career Xi has cared a great deal about corruption. He prioritized addressing corruption as he moved up the Party ranks. He said no public officials who used their position for personal economic gain should hold office. I consider this one of the truly core political impulses for Xi, and many informed people will tell you that one main reason the Community Party selected Xi as general secretary came from his apparent incorruptibility. Among Chinese officials, almost everybody has done something for which they could be arrested, even specifically for corruption charges, because that’s how you got ahead in the Party. So Xi has distinguished himself throughout his career by his commitment to anti-corruption.

When he entered office, addressing corruption was his top priority, and like so many leaders before him, he launched an anti-corruption campaign. But I don’t think anybody anticipated the extent of Xi’s campaign and the degree to which it has continued to grow in strength. Every year since Xi took office, more Chinese officials have been detained than the year before — with already over two million officials involved. We’ve never seen anything like this in any anti-corruption campaign in Chinese history.

And does Xi use this campaign for personal political gain? Absolutely. Some preliminary research has indicated, for example, that at the level of vice minister and above, about 40% of the arrested officials were somehow tied to factions opposed to Xi. And other researchers have noticed that, in the particular provinces where Xi himself has served, fewer officials have faced corruption charges. So it does seem clear that Xi has used this campaign to consolidate power. But it is also the case that the vast majority of officials detained are not personal enemies of Xi Jinping. I think it’s fair to characterize this anti-corruption initiative as genuinely meaningful, with a side benefit that Xi can use it to target political rivals.

And then in terms of the stated objective for Xi’s anti-corruption campaign, solidifying the CCP’s national legitimacy by making officials more accountable to the populace, could you outline some unintended consequences you see: as paranoid bureaucrats and local leaders adopt a passive administrative approach drawing less attention to themselves, as Xi becomes the central executive authority for an ever-expanding portfolio of both major and minute government undertakings, as public associations of the CCP and systemic corruption perhaps get further reinforced, and (perhaps most importantly) as this campaign itself continues to substitute for a more proactive model of governance — one that would operate less through some moralizing retro-revolutionary rhetoric, and more through incisive institutional reforms for better meeting the needs of citizens?

I do think this campaign falls short in a number of different respects. First, it has remained a highly personalized campaign directed from the top, without true rule of law and administrative transparency. And so within the Party elite, certainly among retired Party elders, you do see a pushback and an increasing sense that this campaign has gone too far. Without any established process for this overall campaign, its legitimacy is undermined in many elite sectors. And among local officials, this campaign has certainly contributed to a type of political paralysis, with these officials unwilling to push forward substantial reforms and unwilling to take risks that might draw attention to themselves. They actually fear coming to the attention of Xi or the central Party apparatus — even if only for their successful governance. At any point, an investigation could be launched that may uncover some detail leading to their arrest. And this type of pervasive reluctance and fear of getting out in front doesn’t bode well for the types of innovative pushes that the CCP leadership wants to make in terms of continuing to grow the economy.

And by this point, Xi’s anti-corruption campaign is really just one among several top-down initiatives imposed on local leaders. Local officials already must undertake complicated efforts to clean up the environment. They receive inconsistent executive recommendations about continuing to take on debt, or developing public infrastructure, or propping up the slowing economy. So local officials look at these often-competing directives and just don’t know what to do. The central government might tell you one day that you need to hit certain environmental targets, and then the next might tell you to freeze implementation of those tougher targets because of their impact on the economy.

In terms of the broader Chinese populace, Professor Bruce Dickson at George Washington University has conducted really interesting surveys that have found that although the anti-corruption campaign remains broadly popular, it also has contributed to people starting to think of government corruption as an even bigger problem (the longer the campaign continues, the more officials it implicates). Ordinary Chinese people seem to have doubts about whether Xi ever can resolve this situation. So in some respects Xi’s campaign has in fact contributed to increased distrust of the Communist Party. But Xi has kept pushing on.

Here could we pick up environmental degradation as a primary threat to the CCP’s political authority, both domestically and internationally? To some extent, I don’t even know where to start here: in terms of sensational statistics documenting the ecological, social, economic costs imposed by current levels of air and water and soil pollution, or in terms of government complicity through distorted national reportings and through localized collusion to evade implementation of existing regulations, or in terms of perversely incentivized overproduction and inefficient deployment of so-called green technologies, or in terms of relocating the most pollution-heavy industries to the country’s most marginalized regions while building the infrastructure for long-term coal consumption both at home and abroad — or in terms, of course, of China investing in renewables, and electric cars, and nuclear power on a scale inconceivable amid present-day dysfunctional US environmental policy. So I guess, most generally for a question, what might you see as the CCP’s weakest and strongest claims to providing a model for responsible ecological stewardship, both on a national and international level, both amid yet another America-produced policy vacuum at present, and going forward?

At this point I don’t believe anybody should look at China and think it has created a positive model of sustainable development. Although India has taken the title of most-polluted country in terms of air quality, China still suffers. Most of its cities don’t even meet China’s own air-quality standards, and fall far below those of the World Health Organization or of advanced economies. You still can’t turn on a tap in China and have clean water. It’s the world’s second-largest economy, but it’s struggling to provide basic necessities. And they haven’t even begun to tackle soil contamination, an extremely serious issue in the country. I think China does deserve significant credit for its investment and deployment of renewable energy, particularly solar and wind. But they have yet to take meaningful action that truly addresses the full range of their environmental challenges.

I also want to make clear that any pro-environmental policy has been driven by the Chinese people, much more than by the government itself. The inflection point came in 2013, at the beginning of Xi’s administration. From 2010 to 2012, you had the Chinese people united as a force pushing for political change on the environmental front. The environment had become the largest source for social unrest, with protests uniting groups across geographic boundaries. Old people and young people, cities and villages, were learning from each other’s protests — with all of it amplified by the Internet. You had billionaires like Pan Shiyi ask their millions of online followers: “Who wants clean air?” The Xi government initially said: “It took us a long time to get to this state, and it will take us a long time to address environmental pollution and degradation.” And the Chinese people responded: “We’re not willing to wait.” So the environment, alongside corruption and economic growth, has now become a core issue of regime legitimacy.

The Chinese Communist Party also could look at Eastern European countries and former Soviet republics, and even other Asian regimes, and find environmental catastrophe or pollution emerge as a driving force for the downfall of authoritarian states. So the CCP concluded that they needed to address this problem. And so do they deserve credit for pushing forward on renewables in a substantial way? Yes. Do they deserve credit for advancing electric cars? Absolutely. But if you consider the past two years, and recall how Xi capitalized on President Trump’s declaration to withdraw the US from the Paris Climate Accord: we’ve actually seen Chinese CO2 emissions increase significantly these past two years.

Moreover, I would say that if a country wants to become an environmental leader, that means stepping up and forging agreements on a wide range of global environmental challenges. But whether it comes to methane emissions or HCFCs, you don’t see China doing any of that. Where China can make money by exporting electric cars or renewable energy, we’ve seen them move ahead aggressively. I consider that a positive. But now you already see the government taking a step back from its ambitious air-pollution targets, saying these targets have been a drag on the economy. So although Xi’s administration has shown greater commitment than any preceding administration, by no means has it become an environmental leader.

In terms of China’s global environmental impact, I again think you have to bring in its Belt and Road Initiative. You have to consider whether China simply seeks to export its dirtiest industries abroad. Whether in the cement industry or certainly for coal-fired power plants, China seems to want to do just that. There is documentation of Chinese officials explicitly talking about their plans to send these polluting industries abroad — how they’ll re-establish certain enterprises in Africa or other places, so that these enterprises can continue making money but without polluting China.

At the moment, I believe China has more than 200 coal-fired power plants under development around the world. I think that speaks volumes. Kenya opened its first coal-fired plant as the result of a Chinese cooperative project — and in an environmentally sensitive region. And again China might impose certain regulations on its overseas development, suggesting an environmentally responsible actor, but it has yet to follow its own laws in this arena. Again you see a pretty significant gap between Chinese rhetoric and the reality of Chinese behavior.

And of course the US and Europe have their own problematic models for exporting emissions (say by sending heavy-polluting manufacturing sectors to China). But since you’ve mentioned the BRI a couple times, and have pointed to at least some potential for it to promote more positive developments, could I ask one quick follow up? The Third Revolution describes well how a loosely defined, somewhat improvisatory-seeming nexus of BRI expansion has helped Xi find outlets for China’s overcapacities in coal and steel and cement, and for the exportation of Chinese telecommunications networks, Chinese cultural production and soft-power projections, Chinese capital investments and China-friendly free-trade accords. Along the way, as your book shows, the BRI also has become central to domestic employment, economic growth, and corresponding social stability. State-owned enterprises, for example, play a crucial role in (and have become significant beneficiaries of) BRI projects. So how might a quick focus on the BRI perhaps best help to clarify China’s contradictory posture of claiming to open its economy and society to the world, even while reinforcing a self-serving, state-controlled, neo-mercantilist agenda? And how might the often ingenious overlap of domestic and international objectives pursued though BRI projects make China both more sturdy (or sturdy-seeming) at present, and more brittle in the longterm?

Xi first articulated a vision for the BRI in 2013, in speeches delivered in Kazakhstan and Indonesia. This initiative fit nicely into Xi’s Chinese Dream because it evoked the legacy of the Silk Road and the maritime Spice Routes — and of China’s centrality on the global stage, connecting it to 60-odd countries throughout Asia but also stretching to the Middle East, Europe, and Africa. That initial BRI vision had at its heart a few basic motivations: exploiting Chinese overcapacity in critical industries, linking many of China’s poorer interior provinces to markets outside China, and contributing to the developmental needs of much of the still-developing world.

Over the past six years, of course, the BRI has certainly morphed and evolved into something much grander. It has stretched far beyond even those 60-odd countries. China has basically welcomed the whole world into the Belt and Road Initiative. Most recently, China has discussed a polar connection, to link it more closely to Europe. Xi has welcomed Latin America into the Belt and Road. And as you said, the BRI has expanded from its initial focus on building infrastructure connecting China to other countries by ports, railroads, and highways. It has progressed from building hard infrastructure to constructing digital infrastructure. Today this digital Belt and Road includes satellite systems and fiberoptic cables and e-commerce.

But over time, a series of security concerns has arisen for various countries. China now controls over 80 ports in close to 40 countries. And even though China says it won’t use these ports for military purposes, we’ve already seen PLA Navy ships start to make stops in some of these ports. We’ve seen China establish its first military-logistics base in Djibouti. I talked a few weeks ago with some military analysts in China, who said they fully expect China to develop at least 100 global bases. There’s basically no limit. That whole idea of China not pursuing foreign military bases, and not intruding on the sovereignty of other countries, seems to be going by the wayside pretty fast.

Similarly, you see BRI projects starting to impact the domestic politics of many countries. Chinese officials are training Tanzanian officials on how to manage the Internet, and how to control public opinion and the media. Countries like Peru and Bolivia have adopted surveillance systems based on China’s model. So the BRI has become an all-in-one package for China to support its economic, political, and security vision.

And we’ve likewise begun to see some challenges China faces because of how it does business. Many countries, including some of China’s closest allies (like Pakistan), have started pushing back on some of these projects — sometimes due to the financial terms China has negotiated with a preceding administration, or is trying to negotiate at present. In basically all BRI deals, China says that if you, Country X, cannot repay your loans, then we’ll take Y as collateral. And Y might be a port, as in the case of Sri Lanka, or it might be oil. It might be production from mines. It might be land. And many countries now, many leaders, have started saying that this feels like neo-colonialism, that China does its international business not so differently from how Europe and the US did from the 19th to the early-20th century.

On top of that, you have the BRI reinforcing weak governance abroad, as well as a lack of transparency on environmental protections and labor issues. So what began as a very positive image-boosting initiative for China has quickly generated many, many critics. Of course you see increasingly (especially now with how the US has pushed back) concerns that using Chinese telecommunications and fiberoptic cables, and embedding your whole digital network with Chinese technology, carries all kinds of security risks. You see countries grappling with the possibility that China can somehow start meddling if you make it unhappy. Can it shut down your electricity grid? Or just by importing Chinese digital infrastructure, do you end up overloaded with Chinese political content, as Kenya has? How China negotiates the international pushback against all of this will be interesting to watch.

You also see growing criticism of the BRI within China itself. Some Chinese economists consider these projects fiscally irresponsible. Some Chinese people complain: “Why should we do all of this abroad when we have so many needs at home?” And even the Chinese leadership has started to recognize that while you might sign a favorable deal with a partner country’s current government, its successor administration might resist or reject the bad deals the previous administration struck. So again, for a whole host of reasons, a bit of rethinking has begun in China around how best to pursue the Belt and Road.

Still on digital topics, but pivoting back now to basic differences between the immediate pre-Xi era and the present, shifts in governmental approaches to open public discourse on the Internet illustrate perhaps the most drastic escalation (alongside the detention of Muslim Uyghurs) in domestic social control: with formerly encouraged citizen-led campaigns for increased governmental transparency now drastically reduced (as authorities fear cascading mobilizations of anti-government constituencies), with more than two million government-employed Internet monitors also a critical mass for shaping conversations online. So again in terms of the goals set for Xi’s own Chinese Dream, to what degree do you see the liberalizing digital technologies that emerged in this century’s first decade as having helped to fuel China’s domestic growth? How might longer-term economic development now be most acutely stifled by restricted information exchange? To what extent will Xi’s chances of exporting China’s euphemistically phrased “Internet sovereignty” model hinge on rates of steady social progress which now seem increasingly hard to produce, and which his own authoritarian approach might be further impeding?

Let’s start with the political side. Here again one of the most striking things about the Xi regime has been the extent to which it has married traditional forms of political control / repression with new technologies — how it has dramatically ramped up its Internet activity, for example, both by hiring many more people to do online censorship and monitoring and pro-Party commentary, and by deploying new technologies (while also bringing the big Internet companies like Baidu and Tencent and Alibaba into the fold, and making them responsible for censorship, under the threat of punishment if they fail in this task).

Here again you see this whole technology-based domestic strategy dramatically enhanced under Xi. You see a willingness to use technology in both old and new ways. China has revitalized its system of informants, with many new opportunities to monitor classrooms and neighborhoods and workplaces, and to report any incorrect thoughts or suspicious political behavior. But China also has developed new ways to use cameras. It has installed 200 million new surveillance cameras, and wants to triple that number by 2020. It has developed not only new facial-recognition capacities, but also voice-recognition — and it can even recognize a person by how that person walks. So the fusion of new technology and traditional forms of social control has created an extraordinary surveillance state.

So again, how might this all impact the Chinese economy? Xi’s government still has to grapple with that fundamental question. When you clamp down on Google searches, you get Chinese scientists complaining: “We can’t even access the latest research being done by our compatriots on a global basis. We can’t compete if you keep us out of those discussions.”

Or when you tell Tencent that you’ve just established a government board on video games, and that they can’t produce new video games for the next six months, you harm Tencent not only in the short term, but also in the long term. Potential shareholders now understand that, at any moment, the Chinese government might use its political control to shape the economic future of this company — that even basic investment decisions might not get made according to sound market principles. So again, all of this hinders China’s ability to compete on a global basis, but Xi, at least for now, seems willing to make such sacrifices to ensure that no threat to political stability emerges.

Well here could we also bring back in your book’s account of China’s Orwellian-seeming social-credit system? Here I found particularly fascinating this system’s apparent popularity and elective adoption by so many young people. What might that tell us about the lure of incrementally expanded data-analytics to monitor / reshape everyday life — not just in China, but anywhere? And what might it confirm for China’s authorities about how rewarding conformist behavior can prove even more conducive to population control than explicitly punishing dissenters, activists, or conscientious abstainers?

First, this idea of the model citizen is very Maoist. And using technology to accomplish this goal is really what the social-credit system is all about. It’s a massive social-engineering project designed to shape the behavioral preferences of Chinese citizens. And it doesn’t only track whether you yourself participated in a protest. If your friends participate, that too will lower your own social-credit score. Or if you haven’t repaid your debts, your face might get featured on a big billboard, as a form of public shaming that recalls the Mao era. Today you can even download an app that tells you whether a person who has failed to repay their debts is standing someplace close by. These technologies have introduced new ways of embarrassing people — as well as, of course, rewarding and punishing people based on similar criteria. There are already upwards of 10 million people who can’t board a plane or a train in China because they haven’t repaid their debts, for example.

The social-credit system already has over 40 pilot projects underway, each evaluating a different set of metrics. By 2020, China has promised one integrated overall national program, but even that will include differences among regions. And I do think that, on one level, a social-credit system sounds quite appealing, right? Basically, it seems to just mean that if you adhere to your country’s laws (if you don’t jaywalk, if you don’t misbehave on trains, etcetera), then your country will reward you. You’ll go to the front of the airport line. You’ll get preferential access at a popular restaurant. You’ll sense the real advantages. And you’ll recognize why you don’t want to end up one of those people who can’t board a plane.

Of course new problems will arise, since, first of all, ordinary people don’t know and maybe won’t know exactly what metrics will be used. Similarly, these metrics might evolve in ways that most people find incredibly intrusive. Or again, even if you do nothing wrong, but your friend does, you might get punished, and might need to make a formal apology to get yourself off a blacklist, with a judge determining whether or not you have apologized sincerely. And I sense that this combination of wide-ranging metrics and the capriciousness of the system will only become better known and increasingly problematic for many more Chinese people. For now, many Chinese still might say: “We don’t have a lot of trust within Chinese society, especially outside the family — and this social-credit system can help us to develop that trust.” But the extent to which this thing could become a monster has yet to be fully understood.

China’s authoritarian approach to domestic digital activity also of course points to complex calculations that US and European tech companies face as they seek to pursue the enormous opportunities available if they can break into China’s walled-off markets, and as they assess the risks posed by Chinese companies’ and regulators’ frequent demand for secrecy-breaching technology transfers — as compensation for granting access to China. Within this broader international context of unfair market conditions for American firms, of potential threats to corporate and to US domestic security, and of recent presidential administrations’ (both Democrat and Republican) conciliatory engagement with a hard-pressing China, in which ways might you characterize Donald Trump’s no-doubt simplistic, narcissistically motivated approach to US-Chinese relations as actually steering us, on some points, to some extent, in the right direction? And I can’t ask this question about Trump stumbling his way towards getting one concern mildly right, without asking what his administration has gotten so horribly wrong about constructive engagement with China. So what most stands out in either case? And what would be baseline policy objectives you would set for measuring whether the US succeeds in its own relations with China over the next decade?

It is too early to make a fair assessment of the Trump administration’s China policy. I will say that I think the administration has undertaken a necessary rethink and reset of US policy toward China. It has recognized that the Xi administration is fundamentally different from what has come before, and it has moved to address some of the fundamental problems in the relationship, such as China’s greater assertiveness in the South China Sea, China’s establishment of an uneven playing field in trade and investment, and Chinese influence operations within the United States.

The Trump administration also has been more multilateral in practice than in rhetoric. Although President Trump does not appear to place much value on allies and partners, the foreign-policy bureaucracy has actively engaged with actors throughout the region on areas of common interest and purpose, such as developing infrastructure projects that are competitive with the BRI, and protesting Chinese human-rights practices.

What is missing from the US approach, however, is any thought given to areas of cooperation between the two countries. US-Chinese cooperation has been instrumental in shaping the development of civil society in China, in establishing laws and regulations in areas like the environment and public health, and in strengthening forces of reform within the country. Over the long term, this type of cooperation is essential for the development of a healthy and stable bilateral relationship.