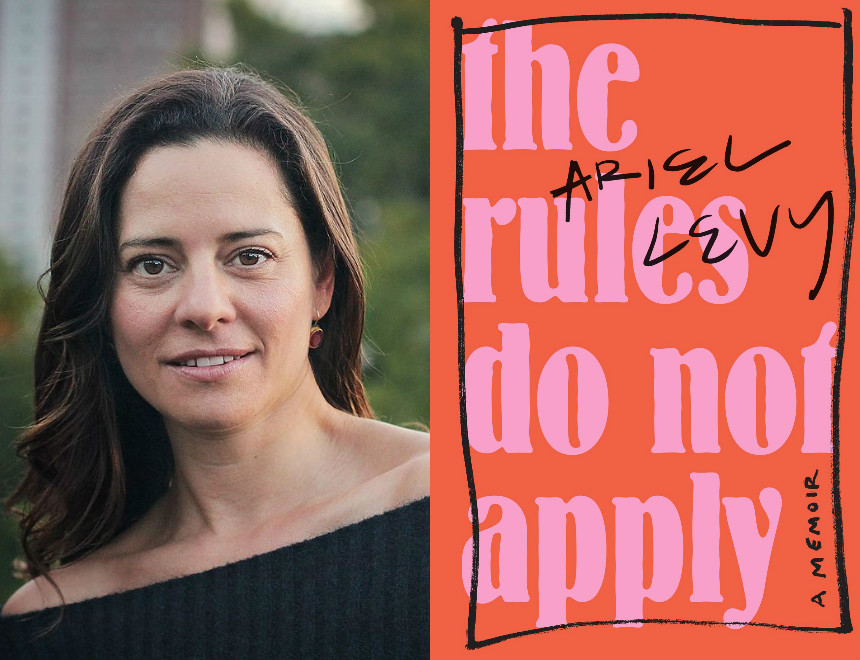

The best way to read Ariel Levy’s memoir, The Rules Do Not Apply, is to barrel along with her at full-speed, not stopping for breath or losing momentum, until you emerge at the other end windswept, tears in your eyes from both laughing and crying, and cursing yourself for reading too quickly. It is a captivating story about the grief of losing the irreplaceable — a son, a spouse, a home — and the jarring realization that nothing can immunize us to the forces of nature, relationships, or the human body.

The Rules Do Not Apply pivots around Levy’s experience of giving birth to her son in a hotel bathroom in Mongolia, and losing him just 10 minutes later. She originally told this story in her acclaimed 2013 New Yorker essay “Thanksgiving in Mongolia,” which won a National Magazine Award. Her new memoir colors in the surroundings of this devastating event, detailing Levy’s childhood in suburban New York, her career investigating the voices of women who are, in her words, “too much” (read: revolutionary, rebellious, badass), and the intimate details of her marriage, including her spouse’s alcoholism, Levy’s infidelity, and the marriage’s eventual dissolution.

Levy has been a staff writer at the New Yorker for nine years. When asked in her interview what she felt the magazine needed, she told David Remnick: “If aliens had only the New Yorker to go by, they would conclude that human beings didn’t care that much about sex, which they actually do.” It is with this forthright humor and self-possessed charm that Levy writes The Rules Do Not Apply, a book for anyone interested in spending time with someone who is candid, unceremonious, funny, and unapologetically comfortable with herself.

ELLIE DUKE: You write about doing your first story for New York: “I was writing about an unconventional kind of female life. What does it mean to be a woman? What are the rules? What are your options and encumbrances? I wanted to tell stories that answered, or at least asked, those questions.” You also talk about being excited from a young age about being a woman. What do you think caused you to feel that womanhood was exciting and beautiful, and got you interested in writing about women?

ARIEL LEVY: The excitement, I think, was that we were excited about going through puberty, we were excited about changing, about the future arriving. It was the arrival of various kinds of maturity. I don’t know if it was that we were excited to be women, we were just excited that there was going to be evidence, in the form of blood, that we were old, we were changing, and that everything would change.

What got interested you in examining womanhood, as a journalist?

I grew up on stories, and if you’re a little girl reading stories about adventure — with some exceptions, but not too many — you have to go through the exercise of projecting yourself onto the male protagonist. If you’re reading about Odysseus, you don’t want to identify with his wife waiting at home, you want to be identifying with him! You want to be the protagonist, that’s what’s exciting. The idea of writing about women leading unconventional female lives was that they were the protagonists, they were the ones making things happen, they were the ones breaking the rules.

You wrote that motherhood felt like relinquishing the role of protagonist in your own life.

I think in many ways that’s true. When you have a kid, that becomes the focus of your attention and energy, necessarily. You have to keep this other person alive. That’s your responsibility and that’s your job, and that trumps all your other jobs.

You’ve said the 10 minutes that you were somebody’s mother will always be part of you. Did you write this book, in part, to cement that part of your identity? And to memorialize your son?

Yeah, I think you’re absolutely right. I think my friends who are parents spend a fair amount of time gazing at their children. And I don’t blame them; I mean, the kids are beautiful. it’s a miracle that you make someone in your body, an actual person! I think they gaze at them, in wonder, a lot. That’s part of the experience of being a parent. And I only got to do that for a very short time. So yes, I think writing about it is a way of gazing, contemplating, acknowledging. This person existed, and that’s important to me.

Was there anything that anyone said during your deepest periods of grieving that was actually helpful or made you feel better?

Yeah, you know, my mom often said to me, “you’ll be okay.” That was really helpful to me, because that’s what you want to hear, right? Not “you’ll have another one,” which my dad said to try and comfort me. Because at that point, I didn’t want another one. I wanted that one. And also, some part of me thought, “well, you don’t know that.” And in fact, it wasn’t true — I couldn’t ever have another one. But with “you’ll be okay,” I was like, “alright, I’ll try to believe that. That seems true.” And in fact, it is true.

The other thing my mom said was “you’re not alone.” And that was comforting too, the idea of bearing the burden with you, feeling some of the pain with you. That was a comfort. And it’s something I try to remember, to say “you’re not alone” and “you’ll be okay,” as opposed to whatever else comes into my head. Because, you know, it’s a perfectly natural human response when someone you love is in pain, you just want to say something to take it away. It’s very normal and human to say the wrong thing to someone who’s grieving, because you’re just desperate to comfort them.

You say you enjoy imposing a narrative onto a complex story — you get to decide what shape it takes — and one of the lessons you learn from writing this memoir is that life is messier and more complicated than that, that you can’t control the story of your life. Has this changed your other writing?

It’s funny you should say that, because somebody asked me that yesterday, like 12 times. She kept asking me, “how has this changed your writing?” and I kept telling her that I don’t think it has. I think it changed me as a person, in some ways, because I was disabused of my illusion of control — or, liberated from my illusion of control is a more positive way to put it. But I’m not sure if it has changed my writing at all, you know? I mean, I’d already been doing it for 20 years. I don’t think I would have dared tell a story this personal had I not already been writing for two decades. By the time I did this, I felt comfortable with myself as a writer. I’d been doing it for a long time — all day, every day, year after year, since I was a kid, and full-time professionally since the age of about 20. So by the time I was going to tell this story, I was relatively confident that I was capable of telling it.

Whenever I write about somebody else, I have to go through a process of convincing them: you can trust me, I know how to tell a story, I’ll do you justice, I’ll be honest, I’ll be fair, I’ll do a good job. And I sort of convinced myself of that, too! I was like, “alright, you’ve been doing this a long time, go ahead.” If this had all happened when I was 30, I don’t think I would have trusted myself to do a good job. Then again, if this had happened when I was 30, the baby probably would have lived. The whole thing would have been a different story.

I want to ask you about “intimacy” in storytelling. You write with a rather journalistic style — very frank, very fast-paced — while telling an incredibly personal, rather devastating story. A review of your book in the New Republic described your book as being “not rendered with any intimacy.” What do you think of that description? Is intimacy different from sentimentality?

I just think that’s demonstrably false, you know? It’s just ludicrous. I mean, if there’s one thing I write with, it’s intimacy. Come on now. If you read this book, and you don’t feel that it’s written in a way that’s intimate, then I just don’t know what you want. That’s why when people ask if that bothered me, I’m like, of course not! It’s just hitting me exactly where it doesn’t hurt, you know?

Because it’s the most intimate story you could possibly ever tell.

Isn’t it, kind of? In fact, I think because I can’t have kids, I have all this maternal energy that comes out in weird ways. So my first response when I read that piece was like, “I should really teach her how to do a takedown. I should call that girl and be like, hey, it’s Ariel Levy, do you want to go over this? There’s a way to do this and you didn’t do it right; I can show you how to do it.” Honestly, I’m not lying to you, my initial response was maternal, professorial.

I want to ask you about political correctness and identity politics.

Oh, by all means, I’d love to talk to you about that!

You went to Wesleyan, you’re involved in this hyper-intellectual lefty world, and you say a few things in the book that might be construed as insensitive — you call the word “heteronormative” a “made up word from the land of academic absurdity.”

Well who would say that in a serious way? I would never be friends with someone who would say that in a real way. If I heard someone say the word “heteronormative” with seriousness I would be like, “I gotta go.” I just think there’s a certain level of that that’s so un-fun and self-serious…

You also talk about a transgender ex whom you have an affair with in a kind of casual way that suggests an indifference to the strict specifics of language…

There’s so much going on in the world that’s actually offensive. If you have time to get bent out of shape about that kind of thing, I just think you should read the newspaper. You know what I mean? If you want to get upset about something that’s not politically correct, how about the fact that a 15-year-old unarmed kid got shot in the head yesterday? Or that 24 million people are going to lose healthcare? There’s so much that’s actually horrible. To police each other on the left, to see who’s the most politically correct, who’s using exactly the right language, like we’re a bunch of Trotskyites…I just don’t have time for that shit. Also, my priority is as a writer. And there are certain things that are asked of language in the name of political correctness that make for really bad writing. And I’m just not going to do it. It’s not my priority.

One of the “rules” you address is fidelity in relationship. You say: “For years, I would resent that Lucy had chosen not to hear me when I told her — from the very beginning! — that I did not really value monogamy. Eventually, it would occur to me that I had chosen not to hear that it was important to her.”

I don’t think that there’s anything inherently immoral or wrong about having non-traditional arrangements around monogamy. I know plenty of people who have marriages or relationships where that’s not a strict rule. But in my relationship, it was not okay. I don’t think it’s specifically an evil thing to cheat on someone, if that’s your arrangement. But it was a very, very bad thing to cheat on her. It was like a deeply selfish and shitty thing to do to someone I love. And a deeply immature thing that I would never do now. Having that affair is honestly my one real regret in life. With everything else, I can follow the path of my own logic. People always ask if I wish I had had kids when I was younger, and I think, well, who knows? First of all, who knows if that would have been successful.

You grew up in a relatively unconventional or progressive household — your father wrote for NARAL and Greenpeace, your mother was a sort-of hippie whose lover would come visit and sleep on the living room floor — but you were surrounded by the convention of suburban New York. And you’ve come to have a rather conventional life, by many standards. What parts of the so-called unconventional aspects of your upbringing have stuck with you?

Gosh, I don’t know. Walking around with this sense of possibility, and thinking: I’m going to question the rules, I’m going to try to figure out what kind of life I want to have, not what kind I’m expected to have. I think that’s what has stuck with me that I’m grateful for.

And that’s what’s good about that mindset, in general. Without people who think the rules don’t apply, you’d never get the first black president. You’d never get Edith Windsor, who I profiled for the New Yorker, who was the plaintiff on the Supreme Court case that brought down the Defense of Marriage Act. I think that’s a very good and productive mindset in a lot of ways. The downside is thinking there are no limits. That can be painful, when you find out that there actually are.

You’ve spent your whole career writing about women like Edith Windsor, and bringing different women’s voices into the fore. What made you think, “now it’s my story that needs to be told”?

After I wrote “Thanksgiving in Mongolia,” I felt like I wasn’t done. I had more to say. And the response to that essay made me think that women wanted to hear more about this stuff, that women were hungry to hear about the primal experience of being a human female animal. I don’t know how else to put it. A lot happens in the lives of half the human population that’s very dramatic — menstruation, fertility, pregnancy, childbirth, menopause, all that stuff — and people don’t talk about it, people don’t write about it. So I realized, maybe people want to hear about this, maybe that’s something I can feel good about contributing to womankind.

Also, I thought if I heard this story about someone else, I would want to tell it, because a lot of the issues I’ve been writing about for 20 years are at play. Why should it be disqualified because it’s my story?