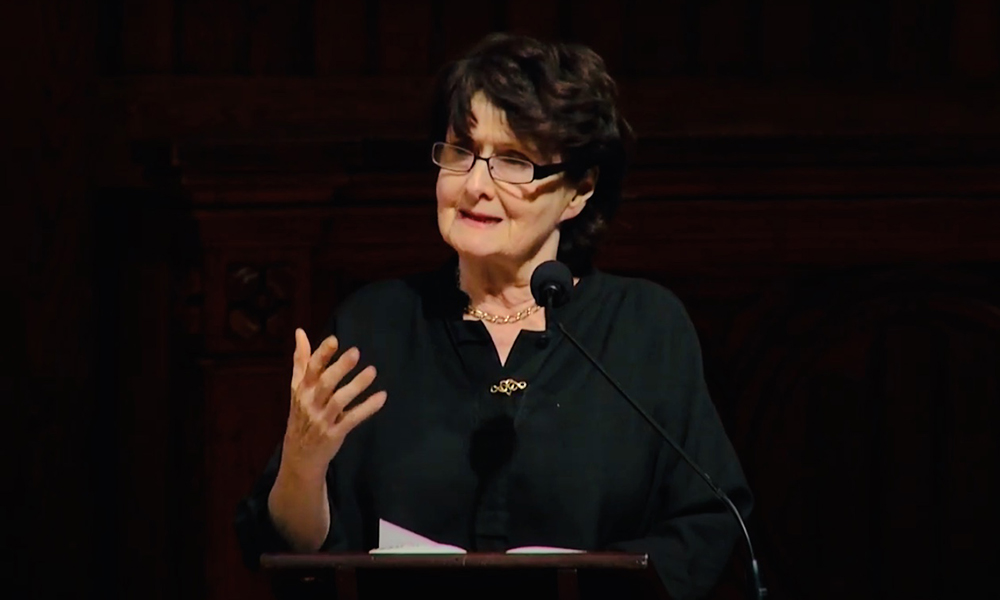

My advisor sent me an email this afternoon to inform me of Eavan Boland’s passing. I could not believe it and did not know how to process it. My memory took the helm and sent me back to the classroom at Stanford University, where the Poetry and Poetics course met every Monday and Wednesday in the spring term of 2018 and I was serving as its Teaching Assistant. Suddenly transported back to my seat, I was waiting for Professor Boland to arrive and start the lecture.

Poetry and Poetics was one of those rare courses where students hold their breath before the professor walks in, anxious to see how and where she would begin. Boland lectured for the most part, regularly posing challenging questions and having students engage in brief debates. She dared students to respond to poems openly and directly. But she also never talked about poems without reading them out loud first, demonstrating our obligation to give poems the chance to hold our attention before we can set out to analyze or criticize them.

The ethical dimensions of reading and writing poetry did not preoccupy her only as a writer, but were also central in her classroom. She never made students feel like she had resolved things one way or the other in her own mind. She engaged them and was genuinely eager to know what they thought. Does the poet owe anything to society? Should poems use everyday language? Can obscurity ever be a virtue? What do we make of the ethically troublesome legacy of many modernist poets? She had a way of making every contribution feel necessary, an uncanny ability to balance different views, and the savvy to relax even the most convoluted ideas into an urgent clarity.

The course was organized around two fundamental concepts: “the poem as history” and “the history of the poem.” These may sound related, but do not always align, and their divergence reveals painful fissures and omissions. Her questions were mainly invested in figuring out how we ought to adjust to poetry — even in cases where the language seems far-removed from the ordinary — to hear the historical testimonies, records and voices that took the shape of a poem because something needed to be said. But she was equally interested in how poetry ought to adjust to us, to individual readers, collectives, and generations who deserve to see their own histories, voices, and experiences reflected in poems. She was the most determined champion of young writers I have ever known.

Because Boland thought it necessary for a poet to always reach out to her community — whether it was academic, national, writerly, or even virtual — she never stopped being a poet of her own time. And that’s one of the reasons why she will always be a timeless poet.

Bing! Another email and I was ushered back to reality. Still unsure of how to process the news, I reached out to copies of Poetry Ireland Review that Boland had recently edited. I needed to read some of her most recent words to block the truth. I started reading compulsively from her introductions. In the 129th issue, she wrote:

Those words on the page, those stanzas, cadences, statements, at their best, can and do lead to a single defining moment: when someone takes down a book, maybe late at night, maybe looking for some confirmation of their own life, and comes upon that poem they want to remember. That moment has held together this art from the beginning. And it always will.

How I loved the way Boland could so effortlessly combine the language of mystery and enchantment with a matter-of-fact plainness. I reread her words:

That moment has held together this art from the beginning.

This verb, to hold, hold together, resonated with me. It sounded so characteristic of Boland’s work. I felt so sure that it must be one of her favorite verbs.

After all, a great many of her poems take place in those in-between moments when things unexpectedly hold our attention like never before, albeit for a brief period: dawn, dusk, the moment when light comes back on after a power cut. “This is the hour I love: the in-between, / neither here-nor-there hour of evening.”

These are vulnerable moments with important things to say, but with so little time to say them. That’s also what great poems manage to do. They hold our attention for a passing moment and they hold the world together, on the verge of new discoveries.

I had a feeling about why this verb, to hold, should suddenly light up, and turned to my favorite Boland poem, “The Necessity for Irony”:

On Sundays,

when the rain held off,

after lunch or later,

I would go with my twelve-year-old

daughter into town,

and put down the time

at junk sales, antique fairs.

“When the rain held off.” Having spent the last few months in Dublin, I knew exactly what a brief and magnificent instance this can be. I could almost see the poet and her daughter looking out the window, waiting for rain clouds to clench their fists, and to hold their breath, so they can finally step out and go into town. Like dry weather, childhood rituals also have a short lifespan. As the daughter grows up and they stop going shopping together, the mother realizes that she had been looking for beauty in the wrong place all along:

that I was in those rooms,

with my child,

with my back turned to her,

searching – oh irony! –

for beautiful things.

I kept browsing through the book to find more occurrences of hold. Meanwhile, to prepare myself to encounter the verb in various guises, I started listing common expressions: hold off, hold your breath, hold still, hold on, and hold on to the memory.

I was wrong. It did not appear that much in Boland’s poetry at all. But for some reason I thought it did. I decided to do what she taught me to do, and turned to an actual poem, to read it out loud and let it hold my attention for a brief moment. I chose a recent poem, “Advice to an Imagist.” It was not easy. Boland had such a distinct voice that all the signals on the page, the words, the line breaks, the punctuation… everything seemed to demand her own inflections.

But it was now time to face the truth. I felt Boland’s voice sinking into the words on the page, and read the poem out loud. At the end of the poem, Boland gives poets an important advice: if you are going to write about salt, she says, do not treat it as a mere object or historical reference. Pursue, instead, “the word that comes / to the edge of meaning /and enters it.”

What a man is worth.

What is rubbed into the wound.

What is of the earth.

All expressions we recognize. Though the word is dissolved, we can still find it. And perhaps all the more powerfully for that. As Boland once wrote, “all depends on a sense of mystery; / the same things in a different light.”