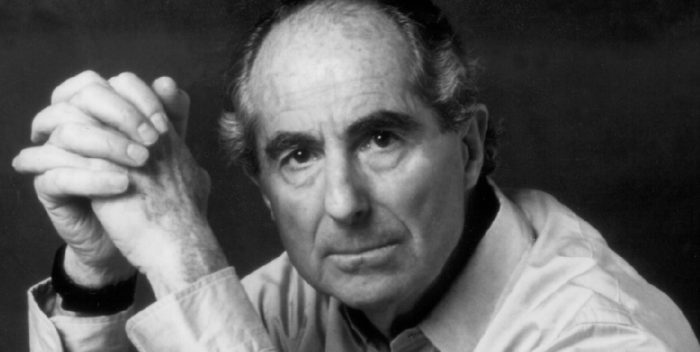

We asked some members of the LARB community to contribute a few words in memory of the late novelist Philip Roth, one of the defining chroniclers of the 20th century American experience. Below is a collection of memories, tributes, and praise of Roth and his groundbreaking novels.

High on the list of things I will miss with the passing of Philip Roth is his ripe contempt for piety — especially ideological piety, of the tongue-constricting kind that disfigures our current political-cultural moment. He once said that the reason he absented himself from New York’s literary-social coteries at the height of his fame was that, when you voiced an opinion there, you discovered you had joined a team.

Roth’s principled defiance of the “correctness” of the Culture Wars was something he enacted avant la lettre, indeed, from 1969, in Portnoy’s Complaint (whose original title, his editor Ted Solotaroff once told me, had been “Whacking Off”), where his careful and, to my mind, loving dissection of a working-class Jewish family in Newark in the 1940s was condemned by many as anti-Semitic for what they considered its public airing of dirty laundry. Similarly simplistic reactions would pursue him unabated, along with adoration and praise, of course, through to the publication of My Life as a Man (1974), The Human Stain (2000), and especially of his masterwork, American Pastoral (1997). Though much loved, this last was also much hated — as I found when I adapted it for the movies — by both “teams”: The Right was unprepared to accept that Roth could treat the novel’s Weather-Underground bomber, Merry Levov, with sympathy — if only the sympathy of psychological insight and understanding. From the Left, Roth’s crime was seen as twofold. To begin with, he portrays Merry in all frankness as the force for destruction and even murder that she is — her career of terror kills four innocent people. But perhaps especially unforgivable from the neo-Marxist point of view is Roth’s narrator Zuckerman’s unabashed heroicizing of Merry’s father, Seymour “Swede” Levov. After all, the Swede is a rich, white, Jewish factory-owner, privileged by nature and culture — and yet not to blame for the world’s injustice and moral disarray: a world in which, as Zuckerman says, Swede must learn “the worst lesson life can teach — that it makes no sense.”

This aspect of the novel’s insistence surfaced at least once while we were working on the film. A director who was involved early on, in 2000, once shared with Roth his interpretation of how the Swede was indeed to blame for what Merry became, because he had not raised her in the faith of her ancestors: Having married the shiksa Miss New Jersey, Merry’s mother, he had more or less guaranteed Merry’s woeful future. After listening patiently, Roth told the director he had gotten the book completely wrong. In Swede Levov, he said, had written the best father, the best husband, the best American, the best man of which he was capable. But, “shit happens,” Roth declared — adding, “Read the Book of Job.” This director was soon gone from the project, which was directed by Ewan MacGregor in 2016.

This tragic, powerful, Old Testament vision at the novel’s heart must, of course, escape any ideologically corrupted reading — the reading of anyone who, in Justice Holmes’ phrase, “knows that he knows.” Neither ideology nor raging partisanship can help us, in this hour of need, to apprehend the deep-going, compassionate wisdom the book has to offer—as displayed in the devastating intellectual humility of its most famous passage. You “try to come at people without unreal expectation,” says Zuckerman. You try to “take them on with an open mind…and yet you never fail to get them wrong,” because it turns out “getting people right is not what living is all about anyway. It’s getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again. That’s how we know we’re alive: we’re wrong.”

Philip Roth will be missed.

People — especially women — talk a lot about Roth’s failure to portray the fullness of female characters, and that’s true. But his creation of full inner pictures of the thought and experience of his male characters, of his heroes, and their travails and their movement through life, is what makes the writing powerful and important and what finally inarguably transcends his woman problem.

I was in college and new to America when Philip Roth’s final spurt of novels was published: Everyman (2006), Exit Ghost (2007), Indignation (2008), The Humbling (2009), and Nemesis (2010). They varied in quality, but there was nothing of his I wouldn’t read. Going to the campus bookstore once a year to pick up the latest Roth became a ritual, and gradually my college reading had to yield to the many novels for which Roth is so justly celebrated: Portnoy’s Complaint, The Ghost Writer, The Counterlife, Sabbath’s Theater, American Pastoral, The Human Stain, and so on. He became my idea of what an American novelist ought to be like: wild, funny, urban, sexy, profane. His relentless dedication to his craft commanded respect; he made writing seem necessary to the simple fact of being alive. And though he was often chided for writing about himself (“No modern writer, perhaps no writer,” Martin Amis once wrote, “has taken self-examination so far”), I can’t think of another novelist who wrote so many distinct and various books. Roth never gave up trying to expand the possibilities of the novel, and for that reason alone he was among fiction’s greatest living advocates, so necessary in these troubled times. “That writing is an act of imagination,” he wrote in The Anatomy Lesson (1983), “seems to perplex and infuriate everyone.”

In many important respects, Philip Roth mirrored Henry James, not just artistically and qualitatively, but also chronologically. Perhaps a better metaphor would be to view Roth as the bookend on the right side of the shelf, and to place James on the far left — with the 20th century between them. For if James began his career roughly 15 years before the turn of century, helping to usher us out of Victorian moralities, Roth ended his roughly 15 years after the end of that same new century, having assiduously and uncompromisingly written against all manner of social and ideological pieties, only to die a few years later, during a time when freshly risen moralisms, decked out in different clothes, are once again exerting their restrictive, condemnatory influence on artistic, intellectual, and social freedoms.

Philip Roth converted Henry James’s commitment to unwrapping experience into an almost prosecutorial mode of investigation — you sometimes have the feeling that Roth’s subterranean drillings into the deepest processes of the mind are being executed before a highly discriminating jury. He permitted his characters to be approached with as much suspicion as empathy; they certainly were granted the ultimate freedom: to be irresponsible, to tell themselves and others stories, to be as flawed and confused and wrong as people, if we’re being honest, are — particularly in their conduct with one another, and with themselves. To his bewildered characters, as to the confusions of life itself, Roth applied an interpretive intelligence that, I believe, is the reason to read Roth — indeed the reason he will continue to be read.

That, and how sane his writing is. If Roth made little room, in his work, for the salubrious aspects of love and spirituality, he certainly captured — often breathtakingly — how both could veer, in the hands of people, into insanity. And this was Roth’s great feat: to give us our sanity while showing us its opposite.

I get to write books about a hitman pretending to be a rabbi because Philip Roth made it safe for Jews to skewer Jews, he took that weight first, to make comedy of often tragic American Jewish life. Jews don’t have many superheroes, but in Roth Jewish writers found someone who embodied the greatness of both intellectual pursuits and the ineffable truth of life as witnesses to history. Which is to say that we laugh at the wrong time, we sometimes love the wrong people, we put parts of ourselves in places that maybe they don’t belong, but we do it because to be comfortable as a Jew in America is to be naive. His writing was always about the constant struggle of identity, of reckoning with the sense that we are born to die, and that in between trying to figure out who we are and the grave, well, there’s much that we can get wrong. I am ever grateful for his gifts. I am ever grateful for the risks he took with his art. I am ever grateful to have lived when he lived. Dayenu.

The 25th anniversary of the publication of Portnoy’s Complaint fell on February 21, 1994. What luck: This was also my 44th birthday and a Monday night, timing that allowed me to give myself and 300 other Philip Roth fans the present of a surgical downsizing of the book into a two-and-a-half-hour dramatic reading at Manhattan Theatre Club. The genius casting department of MTC, where I was then the director of the Writers in Performance Series, landed Ron Silver as the reader. Philip (before I called him Philip) told me, with just a modicum of concern, that my editing scalpel had left only the “arias” of the book in place, but, the stars aligning, he was easily persuaded that the whole opera would still be heard. The night of the reading, a primed Roth and an adrenaline-fired Silver, who’d arrived late having only just read the “script,” spent fifteen minutes talking in the dressing room.

And then: Silver delivered a spectacular rendition. You could practically feel the home runs bouncing off the ceiling. It was thrilling, from start to finish.

The rest, alas, is not history. Philip and I and two ardent producers tried to mount the “play” as a real production, and had a joyful time of it, as long as it lasted. Putting on a real play in New York City takes enough time to start and finish a book, if you are Philip Roth. The earliest, pre-publication reviews of Sabbath’s Theater suggested the protagonist as a kind of aging Alexander Portnoy. Philip was not about to allow that key work of his youth to rear up in competition with the novel he had “sweat blood” over, the one he went on to place as the best of all his novels.

But, for me: On my birthday, in 1994, was born one of the most deeply treasured friendships of my life. How it can be over, I will never understand.

As a teenager growing up in Kansas City, reading Portnoy’s Complaint changed the way I thought about the world. In that amazing and fearless book, Roth showed me that anything was possible, not just in fiction but what you could have sex with.

Philip Roth’s Last Peach:

In 2010 I was working in the trade division of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt as a publicity assistant, a job for which I was fundamentally unsuited and would surely have lost had I not escaped to graduate school a year later. My boss, the tiny, terrifying director of publicity, managed two authors, one of whom was Philip Roth. When we got galleys of Nemesis, which would be Roth’s last novel, I was put in charge of the grunt work involving them: mailing copies to the nation’s book review editors and radio hosts, writing press releases to slip inside their front covers, making inquiries for a circumscribed book tour.

It took just a few subway commutes to read through the brief novel about a polio outbreak in Newark, though I would stare at hundreds of iterations of the yolk-yellow cover for many months.

“You don’t actually need to read the books,” My boss said, her thin eyebrows raised.

But of course I was going to read the new Philip Roth novel. When I first read American Pastoral, in high school, Roth became to me what Chinua Achebe was to Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie, the writer who makes you say — Oh! You’re allowed to write like this? You’re allowed to write about families like mine, about people like me? About the bickerings and flailings of the Jewish nouveau upper-middle class? About dull small cities and fridges loaded with dishes of leftover tuna salad sheathed in plastic wrap? Roth showed that you could do this. You could do it beautifully. I’ve come to realize he was not alone, that there was Bellow and Malamud and Heller and the rest, but for now I kept reading Roth: I started Portnoy’s Complaint on a stationary bike at the gym but got embarrassed and had to continue in private. The Plot Against America I read in a shared fifth floor studio in France during a semester abroad.

I did not think Nemesis was Roth’s best novel, and at 23 I struggled not to mention this in the press release. Still, one moment in it struck me as terribly important and good. Near the beginning of the novel, Bucky Cantor, the working-class protagonist, pays a spontaneous visit to the well-appointed home of his girlfriend’s well-heeled parents, and he ends up almost accidentally asking her father, Dr. Steinberg, for permission to get engaged.

Why the sudden onslaught of confidence? In the big, beautiful house Bucky feels not just the comfort of wealth, not just pride in Dr. Steinberg reassurances that Bucky is doing his part to help manage the Newark polio outbreak. He has a revelation while eating a peach.

He bit into a delicious peach, a big and beautiful peach like the one Dr. Steinberg had taken from the bowl, and in the company of this thoroughly reasonable man and the soothing sense of security he exuded, he took his time eating it, savoring every sweet mouthful right down to the pit.

A few sentences later, Bucky asks for Marcia’s hand. As the novel turns and darkens with disease, Bucky’s thoughts return several times to that “wonderful peach,” a juicy symbol of — what? Prosperity? Security? Pleasure? Sheer wonder at the possibilities the world might hold beyond the bounds of Newark’s Weequahic neighborhood?

This ultimate peach is not the only stone fruit with which a Roth character takes up Prufrock’s dare. Roth began his fiction career with a significant cornucopia in Goodbye, Columbus, published by the house then called Houghton Mifflin in 1959 when Roth was just 25 years old. Good fruit plays precisely the same role here as it would a half century later. Neil Klugman, raised in a poor section of Newark, encounters fresh cherries and nectarines — treasure foreign and initially forbidden to him — when he opens the second refrigerator at his wealthy girlfriend Brenda Patimkin’s family home:

It was heaped with fruit, shelves swelled with it, every color, every texture, and hidden within, every kind of pit. There were greengage plums, black plums, red plums, apricots, nectarines, peaches, long horns of grapes, black, yellow, red, and cherries, cherries flowing out of boxes and staining everything scarlet…. I grabbed a handful of cherries and then a nectarine, and I bit right down to its pit.

“You better wash that or you’ll get diarrhea,” Brenda’s snooping sister says, eviscerating the epic catalog.

How unimaginable is the wealth of the postwar American “haves,” who can now, thanks to advances in agriculture and transportation, fill their refrigerators with an orchard’s worth of fresh riches — enough sweetness to make a fruit lover sick. Poor Neil gorges himself on the literal fruits of modern prosperity, hoping, perhaps, that by consuming luxury, he can incorporate their meaning into his very being. But he cannot hold on to fruits that give him so much cause for wonder. Indeed, it may be that we wonder precisely at those objects and ideas that we are impossible to hold onto, difficult to digest.

We would fill huge soup bowls with cherries, and in serving dishes for roast beef we would heap slices of watermelon. Then we would go up and out the back doorway of the basement and onto the back lawn and sit under the sporting-goods tree, the light from the TV room the only brightness we had out there. All we would hear for a while were just the two of us spitting pits. “I wish they would take root overnight and in the morning there’d just be watermelons and cherries.”

“If they took root in this yard, sweetie, they’d grow refrigerators and Westinghouse Preferred. I’m not being nasty,” I’d add quickly, and Brenda would laugh, and say she felt like a greengage plum, and I would disappear down into the basement and the cherry bowl would now be a greengage plum bowl, and then a nectarine bowl, and then a peach bowl, until, I have to admit it, I cracked my frail bowel, and would have to spend the following night, sadly, on the wagon.

What purpose does this fruit serve, besides setting up a joke? (Nemesis is not as funny about fruit as Goodbye, Columbus.) The fruit is sex, of course — this is Roth. It is wealth and everything wealth promises — think, too, of the dripping beefsteak tomatoes meant to signify country joys in American Pastoral. Fruit is fertility, the promise of the future, of hard work and care being rewarded with sumptuous sweetness (and punished with gastrointestinal distress).

I tried to include something about the revival of the peach motif in a Nemesis press release, but my boss rightly vetoed the idea. Only “breathtaking” and “masterful” and “dazzling” could stay.

I met Roth a few times while working at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Generally I was carrying loads of books for him to sign, and I made no impression on him. He was dry and bored with our fussy attentions, yet still funny, and he looked just like my mother’s best friend. They were both tall and gaunt and had the same category of Jewish face: long, narrow, with small, close-set eyes, a blade of a nose, lips pursed like a drawstring bag. I wonder if other Jews share the experience of seeing familiar faces repeated on strangers. I have occasionally seen Michael Pollan’s likeness in a magazine or on TV and have momentarily mistaken him for my Uncle Ronnie.

Philip Roth looked like family; he is a part of my literary family. But in 2010 I was a shy young woman and I never asked Roth for so much as an autograph, not wanting to seem like a twittering fan girl. As I prepared to leave publishing to get a PhD, I took one liberty: I sent Roth a handwritten letter directly to his New York address, unsigned, explaining how much his work had meant to me. No doubt he tossed it immediately. I should have typed it so I could see now what I wrote then.

In graduate school, where having opinions about literature is permitted and occasionally encouraged, I thought of Roth mostly when the Nobel announcement rolled around and again he did not win. I studied the Modernists: Woolf, Joyce, Eliot. Few Americans, no Jews. Years passed; I wrote my dissertation on representations of agriculture in modern literature as a response to urbanization and industrialization. Looking back now on Goodbye, Columbus!, I realize with surprise how neatly a chapter on Roth would have fit into my work on the mythos of an idyllic agrarian past. Brenda Patimkin whimsically wishes her watermelon seeds and cherry pits would sprout into vines and trees, and cynical Neil assures her that seeds planted in this affluent suburban yard would produce only “refrigerators and Westinghouse Preferred,” the electric products of an industrialized present. The modern suburbanite can preserve rural products through refrigeration, and she can represent rural life in art and words, but she cannot actually reproduce a vanished or mythical mode of living.

I was about to submit the dissertation when, last June, The New Yorker published Roth’s essay “I Have Fallen in Love with American Names,” and suddenly the 50 years of peaches made more sense. In the essay, Roth claims he has always thought of himself as an American writer, not Jewish-American. As usual when reading Roth, I felt the awful shock of recognition. Roth writes that he was a grandchild of “those 19th-century Jewish immigrants, whose children, my parents, grew up in a country that they felt entirely a part of and toward which they harbored a deep devotion — a replica of the Declaration of Independence hung framed in our doorway.”

I am also the grandchild of Jewish immigrants, albeit of the 20th century — they fled Germany during the Holocaust. They also settled in a small, working-class city near New York. Their son, my father, has a copy of a letter by Thomas Jefferson taped above his desk at home. He saw the original at an inn in Rhode Island, and when he couldn’t find the letter in a book, he asked the inn to type up the text for him. The letter is about the importance — and fragility — of religious freedom in this country.

As he always did, Roth disappointed me with his misogyny in the essay: the American writers he lists as early influences includes zero women. Also zero people of color. I think there may be a strain of misogyny particular to some Jewish men, Roth among them, who see themselves as the sole representative of the cultural “other,” and thus see other “others” not at all. Consider, as a random example, Stephen Greenblatt’s claim in a New Yorker essay published a month after Roth’s, that “sexual selection” in Jews had long favored “slender, nearsighted, stoop-shouldered young men” who were destined by evolution to become scholars. And what about the young Jewish women — are we chopped liver?

But to the point. Roth’s essay showed me that, whatever qualms I had with his work or youthful insecurities with his person, I had never really left him behind. Roth’s wistfulness for “American names” showed me why he bookended his fiction career with weighty peaches.

The male authors Roth read as a teenager were, he writes, Southerners and Midwesterners “shaped by the industrialization of agrarian America, which caught fire in the 1870s,” and “shaped by the transforming power of industrialized cities.” They were largely rural writers adapting to a world in which Big Business was radically transforming their remote old places. (Where was Willa Cather in his list of influences?) Roth, meanwhile, was a city kid engrossed in America’s “distant places, in its spaciousness, in the dialects and landscapes that were at once so American and yet so unlike my own.”

Roth was obsessed with the mythical places where the peaches came from — that other unknown, unknowable globe. I was just like him, even if I channeled my need to understand the idea of heartland differently. After growing up in the suburbs and college in the city, I escaped, within days of graduation, to work on a farm and try to figure out what the world was outside of my narrow social circles. I studied farms and the books people wrote about them. I got my hands dirty; I wrote long analyses and conference papers and jargon-heavy articles. I made the work of agriculture — and the American it stands for — more real and less wonderful.

Roth doesn’t go to the farm. Instead, by bringing fruits into his narrative, by making them a sort of gateway to adulthood, to sex, to marriage, to wealth, he brings the exotic old rural landscape into the modern city; he brings the mystery of the agrarian life he liked to read about into the industrial now. He preserves the wonder of the sweet unknown.

Roth is capacious. Since his death on May 22, many affectionate remembrances of him emerged, and many more will — and in each one Roth comes off as an entirely different writer and person: the lover of baseball in one, of swimming in another; the arbiter of male sexuality, the epitome of male ignorance, the sculptor of Jewish American identity, the sculptor of American identity. That he contains so much for so many people is how you know he’s good, and that his work will last. For me, for now at least, he lasts as the novelist whose peach disturbed the universe. With a nectarine, with a peach, Roth infused the everyday hustle with wonder, with amazement that our dirty little world is as it is. If I hold on to one thing about Philip Roth, it will be this: more than any other writer, for 50 years he held onto his sense of wonder. He gave us wonder. I hope I said as much in my letter.