During the two terms of President George W. Bush, I lunched every other week with food critic Jonathan Gold and novelist Michelle Huneven. These were long, agenda-less, winey meals in which conversation followed the contours of our current obsessions, meandering from books to politics to our projects, our families, adventures from our younger days, the stranger or more embarrassing the better. Sometimes you do not recognize a golden era when you are living it.

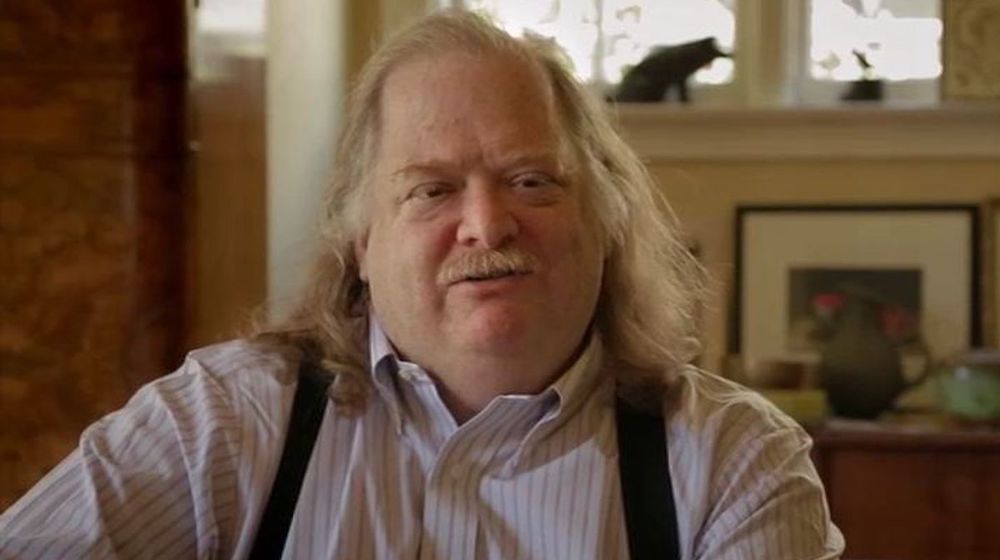

The three of us formed a comfortable and I would say sibling-like triangle. He was almost a foot taller than both of us, ground huggers at 5’2” and 3”. Wispy ginger hair surrounded his large head like a halo and just touched the suspenders on his shoulders. He carried his girth with dignity that some years later morphed into majesty. Sometimes we hugged or kissed when we met and said goodbye but usually we didn’t, because those types of formalities seemed formal.

Michelle and I both felt perpetually guilty about devoting a chunk of the work day to a meal, but we gave ourselves passes for mental health. For Jonathan of course it was his job, though you wouldn’t know by observation. We hardly discussed food. I never saw Jonathan take a note, and I never received a follow-up email asking me if I recalled some ingredient for his clarification. We ordered what we liked, though Michelle and I always asked if he had already had the Poc Chuk or Dan Dan Noodles, because we knew he needed to try as many menu items as possible. We ordered what we liked and then he added about 12 more dishes for the now note-taking server who usually betrayed no surprise but seemed to respect the scope of our commitment.

We rode the peaks and valleys of these bountiful meals, from the agitating interlude before the arrival of the first dishes, to the greedy plunder, which always gave way to the slow sipping of the last of the wine and then coffee or tea when conversation tailored off into a drowsy state of well being, the way you might spend an afternoon vacationing in a European food city. The listless sampling of desserts was often the setting for one of Jonathan’s surprising one-liners, delivered after the long pauses in which his genius brewed.

One discussion began with newly reported details of Prescott Bush’s protection of Nazi gold, sailed into the short stories of Anton Chekhov, and ended in a fascinating disquisition from Jonathan about the properties of the ink sac of the squid. There followed a wine-saturated silence.

Jonathan broke it. He said, offhandedly: “It is pleasant to know things.”

I frequently repeat that sentence in my mind and savor it.

One day I reported on my dinner at the home of a food editor of whom Jonathan was not overly fond. “What did she serve?” he and Michelle wanted to know. “We started with some grilled scallops and wilted spinach,” said I. Jonathan asked, “Beurre blanc?” “I think it was balsamic vinegar,” I said, remembering the condiment on the kitchen counter.

After yet another deep drink from his wine glass and a bit of silence, Jonathan softly declared, “Balsamic vinegar is the last refuge of a scoundrel.”

Difficult to describe why these lines gave us so much pleasure; at the time we simply nodded, satisfied that the day ended with a solid Jonathan-ism.

Afterwards we often accompanied him to some grocer or butcher that he had discovered; I remember several trips to Howie’s market in San Gabriel, to the butcher in the back, where I would buy whatever cut of meat Jonathan and Michelle ordered. I loved being a lazy acolyte. Though I was two years older than Jonathan, I slipped into my role as youngest sibling, content to follow along and trust I would learn invaluable lessons. Our lunches continued into Obama’s first term but petered off in the second. Michelle was teaching at UCLA and was always working on her next novel, I got involved in the founding of the Los Angeles Review of Books and a book of my own, Jonathan of course won the Pulitzer and went back to working at the Los Angeles Times, and his commitments grew and grew. Though my husband and I still dined with Jonathan and his wife Laurie Ochoa several times a year, the era of those sublime irregular days was over. I always thought we’d return to them when we got a bit older. Now I know that’s all I’ll get. It will be enough, though no amount of time would have been enough. Just one more thing I learned from Jonathan.