Allison Miller does funny things with drips. In “Jaw,” one of seven paintings in her current solo show at The Pit in Los Angeles, drips slide up the canvas in defiance of gravity, while others flow down as expected — clearly, she changes the orientation of her pictures as she works. Miller’s drips are not simply byproducts of her process, as in Franz Kline, for example; but instead, have been carefully preserved. She places tape over the drips she wants to isolate, then removes it only toward the end, preserving rectangles of color around the original drips so that they stand out against the final surface. It’s a goofy send-up of Abstract Expressionist marks with their connotations of emotional urgency and dramatic creativity, but also a canny way of reintroducing the drip as painterly language that escapes the confines of cliché.

Tape has a history in hard-edge abstraction as a tool for precision, Al Held’s work being one example. Hard-edge painters use tape, but leave no trace of it beyond a clean edge of color. Miller takes the opposite tack. Each piece of tape she applies leaves its footprint, an indexical mark that displays Miller’s artifice overtly and even oddly. This feels consonant with the whole of her painting language, which despite being intentionally clunky, is utterly ravishing. Hers are gorgeous paintings assembled in a jarring manner, — different from the ways we are accustomed to encountering beauty. Miller, an LA artist with eight shows under her belt here and in New York, deserves the attention she is getting, and more.

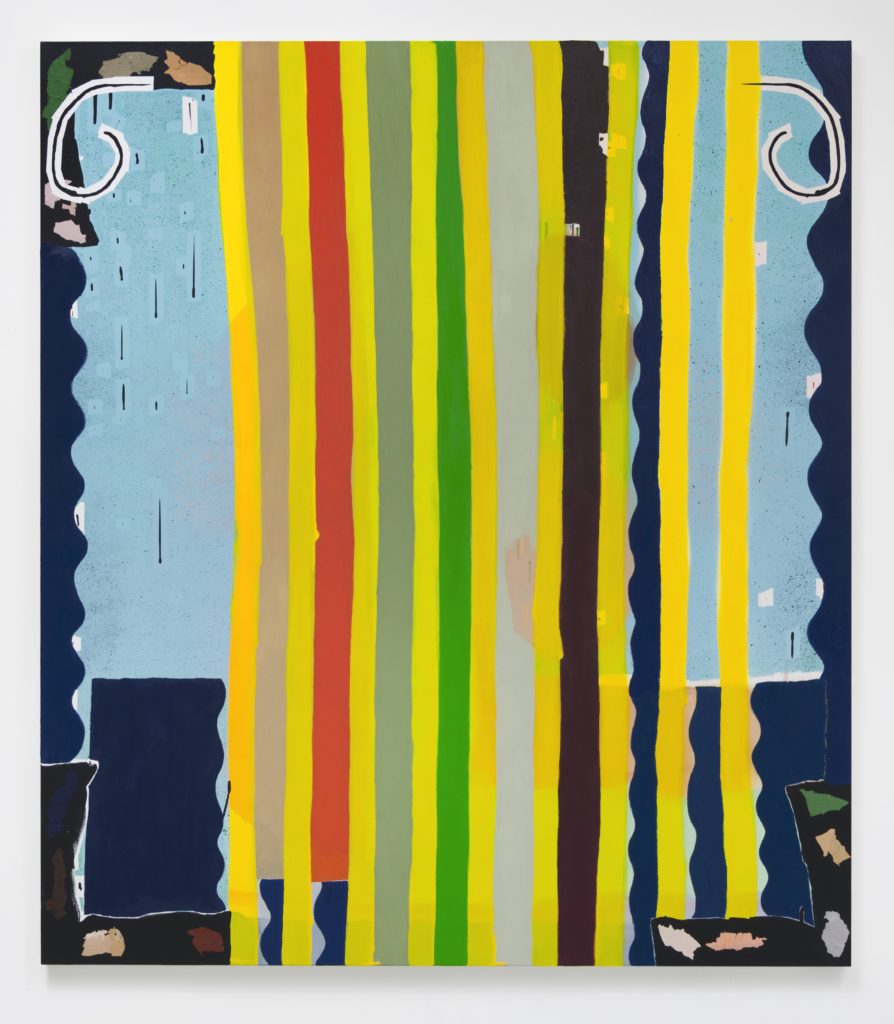

In “Corner,” the picture is organized around a large chevron whose apex touches the center of the canvas’s top edge, dividing the upper half of the canvas into two equilateral triangles on either side and one large triangle below. The chevron itself is composed of dusky grays, browns, and beige, except for one section of intense green that erupts outward, stopping just short of breaking the painting apart. The canvas’s upper portion is smooth aqua, retreating behind the chevron, while the triangle at the bottom contains bands of brown, dark blue, and maroon, set off by a saturated primary yellow. The painting revolves around its mad orchestration of yellow and green within a neutral environment, earth colors suggesting the terrestrial while aqua serves as a sky above. Confounding these associations are linear streaks of paint flying in groups across the canvas, each streak starting red, becoming green, then finishing blue. The streaks are like schools of fish, or, when descending through the painting, like burning raindrops. Floating on the left side above the chevron are black hook-like forms, which relate to nothing in particular but successfully cool down the painting, preventing the chevron from subjugating the visual field.

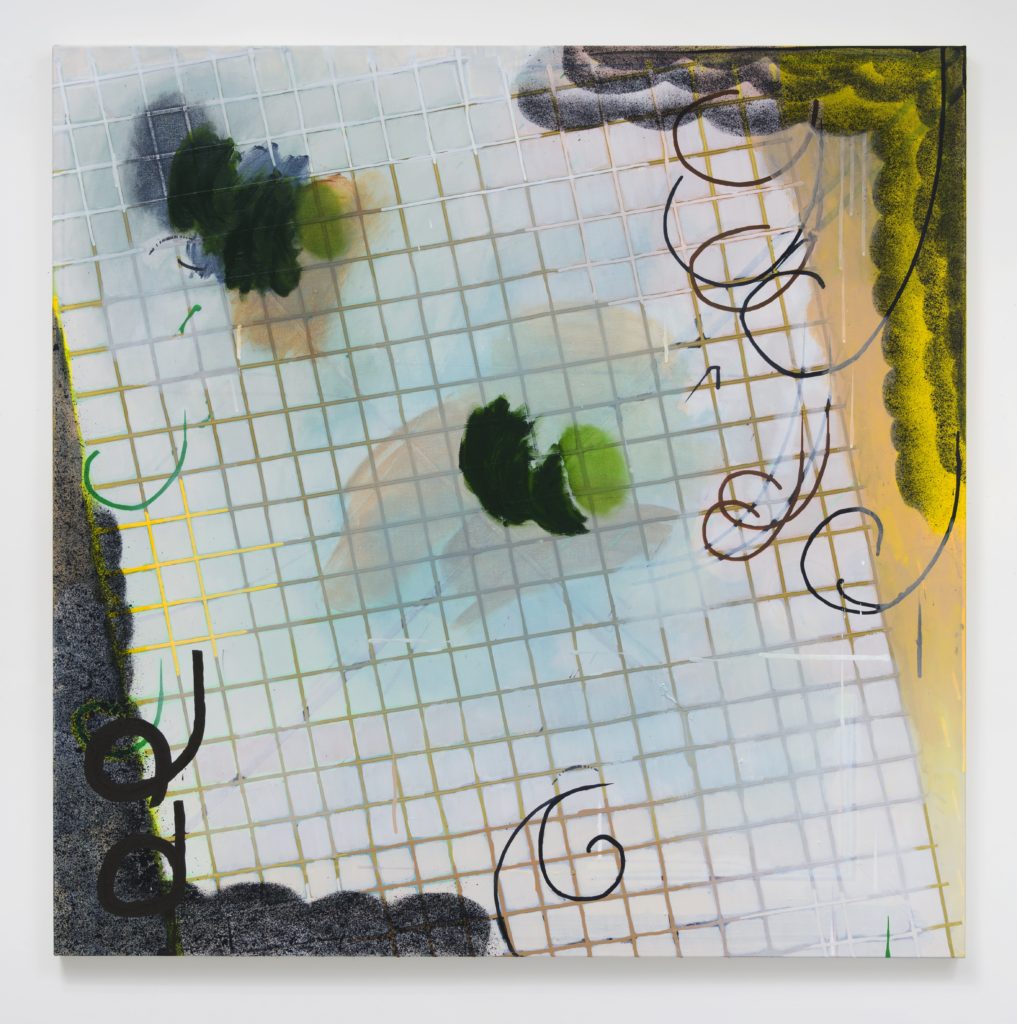

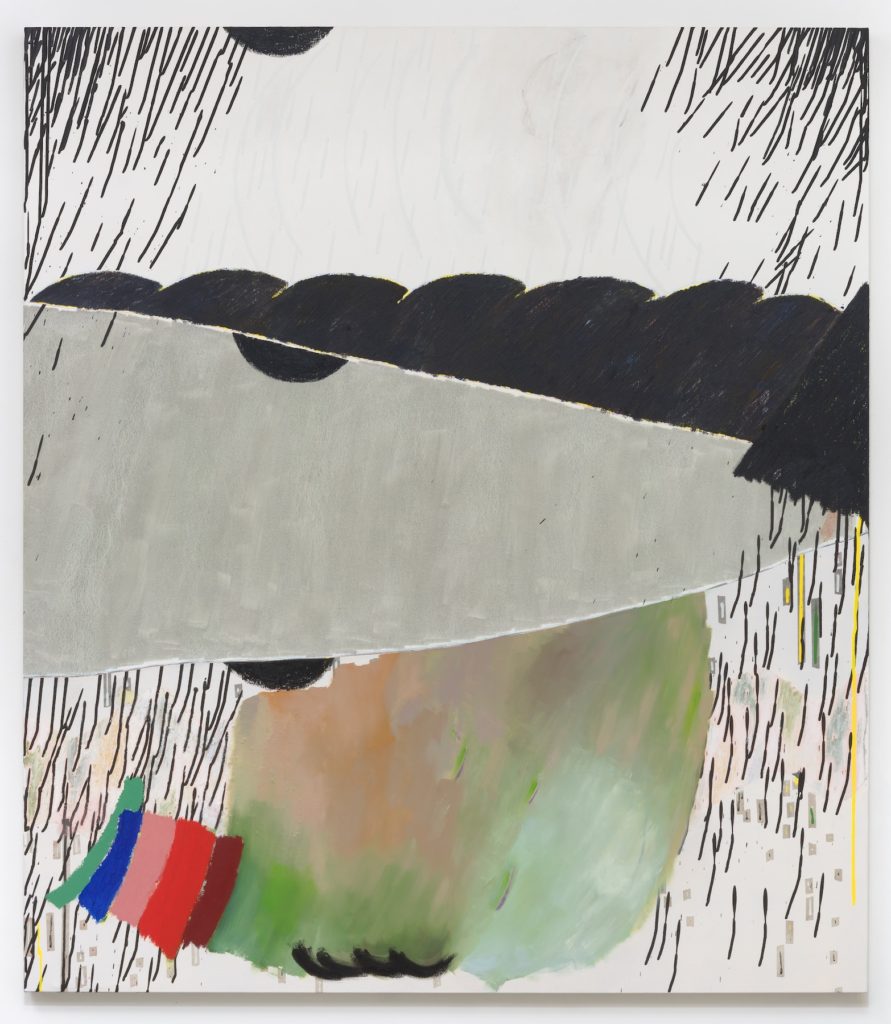

Miller uses her dialogue with historical painting conventions as a crowbar to break into fresh territory. “Door” has strong landscape associations owing to orthogonals that read as horizon, fields, and paths, a compositional device used often by Van Gogh (“A Wheat Field With Cypresses” (1889) is a comparable example). In “Screen,” a square canvas, I could see an early layer where she made a large X extending to the canvas’s four corners. Over this she painted a grid, but the grid sits at an off-kilter angle rather than parallel to the square’s vertical and horizontal axes. Miller disrupts the grid without actually destroying it: she has smeared it away on the far right, painted curving lines over it in black, brown, and green, and smudged on dirty, grassy passages. The bottom left and upper right of the painting are occupied by cloud-like shapes of spattered black, which turn the curving lines into symbols of gusting wind and weather, finally transforming the hoary device of the grid into a mundane window screen. It is as though Miller took Agnes Martin’s transcendent horizontals and verticals and recast them as a simple encounter between weather and shelter, suggesting that the quotidian is no less profound than the spiritual. In this, the two artists are not opposite but adjacent, as though Martin were a point on a circle from which you travel away as far as possible, until you finally complete the loop and find yourself back where you started, holding Martin’s hand. The fact that Miller’s often noisy, jolting works can find a connection to Agnes Martin speaks to their powerful foundations.

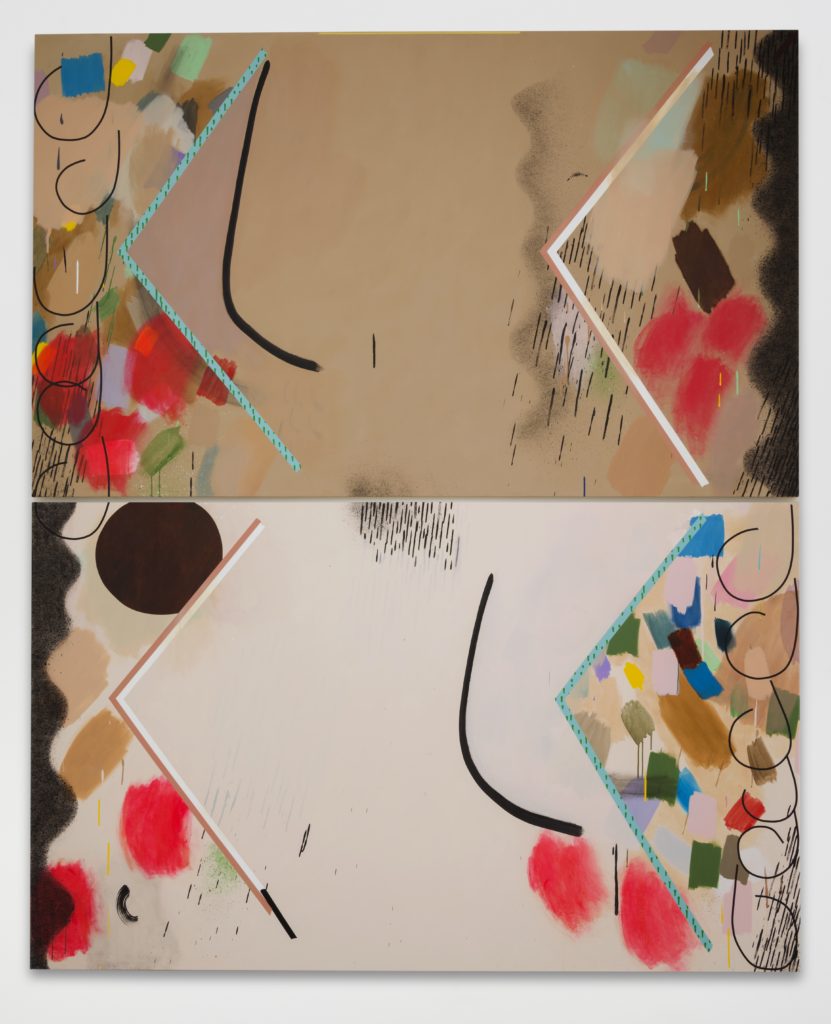

“Bed” is a diptych of two stacked paintings, Miller’s largest piece to date. In the top canvas the field of action is an expanse of calm tan, while the bottom half is lighter and creamier. Both are colors my wife happens to favor in bed linens, and I have to admit they are relaxing to sleep in. Against this sedative, Miller has created a cacophony of hue and gesture crammed into the left and right margins. The centers of both canvases are held quiet by chevrons turned on their sides to bar the loud chorus of colored strokes from infiltrating inward (a few marks do break through).

The entirety of “Bed” is built upon a chiasmus, the upper half and the lower half symmetrical in reverse. On top, the left chevron is aqua with green drips, and the right chevron is composed of one brown strip and one white; these are flipped in the canvas below. The diptych’s bottom left and top right feature boisterous patches of reds, yellows, blues, pinks, greens, and browns, brushed on hastily, often thinly, along with a column of curving black lines that start off open then curl in on themselves in a progressively closing gesture, like a letter “J” forming in stop-motion animation. The marks in the paired canvases’ top right and bottom left, on the other hand, are fewer and larger, in only reds and browns, with densely spattered black dots defining undulating curves that run along the margin. Miller’s clusters of linear black marks fall like rain throughout the diptych, creating speed and motion. Her use of chiasmus to organize the painting evokes a couple in bed, grown symmetrical over the years despite their differences.

Miller offers a valuable model for addressing problems in painting, and problems in general. Her works are fully aware of their history, particularly earlier abstraction, but are in no way limited by these precedents. The paintings do not announce their art historical concerns directly, they are embedded and available for discovery. Miller has taken the incomplete, awkward gestures, and unstable qualities that came to be called “provisional painting” and remade them into layered works that, for all their spontaneity, arrive at a carefully established resolution. Her work asserts its unique identity above all else, each painting oddly idiosyncratic, like encountering a rare plant or animal that has evolved bizarre traits in order to exploit an unusual ecological niche.

To my eyes, Miller is a master of what the poet John Keats called Negative Capability, the capacity to work through and within a state of uncertainty. She has developed a vocabulary of visual elements that turn up in multiple images, including lines that curve on one end like a letter “J,” cloudlike spatters of black paint, and clusters of short lines that school like fish in different directions, but none of these add up to a sameness across her work. Miller’s capacity for the unknown allows her to arrive at novel and fascinating outcomes in her paintings, with unpredictability the most notable through-line. Her investment stands in sharp contrast to our 21st century culture of chain restaurants where you know exactly what you will receive before you even walk in, of mainstream Hollywood movies serving up unsurprising, market-tested fare in the form of superheroes and formulaic romance, and of a political system so stuck in routine that it could be ambushed by a reality TV huckster jumping into the presidential election like a joker in a deck of cards. It is a challenge to remain alert on the lulling sea of bland sameness, and Allison Miller’s courage is bracing.