On an afternoon of autumn rain in 2001, Yi-Ho, Yu-Chieh, and I revealed our crushes to each other and decided to name them the Eye, the Nose, and the Mouth. It was the first time I ever confessed my desire for boys to anyone. It was also a time when secret solidarity came before self-identification, when sisterhood came before identity politics. At the age of 12, I did not identify myself as gay. Instead, I came to my gay consciousness through desiring a boy along with other girls. It was in the same autumn that we decided to become S.H.E. By then, we did not expect that it would become a friendship of a lifetime, just as how S.H.E never expected that they would produce the most enduring myth of female homosociality in the Chinese-speaking world.

Earlier that autumn, S.H.E debuted on the music scene with their first album, Girl’s Dorm. The title of the album foretold what the girl group would mean to the queer generation of post-millennial Taiwan. It embodied a feminine and queer time and place — a time when girls go through the angsty years of teenage together, and a place where they learn how to structure their lives to one another. At first, it was merely a marketing strategy. The group’s management company, HIM Music, arranged them to live together in a dorm so they could get to know each other. But something about the arrangement spoke to the girls and queer boys of my generation. S.H.E was certainly not the first girl group in the history of Taiwanese pop music, nor were they the only one singing about female relationship. In the mid-1980s, City Girls became wildly popular with their megahit, “Live While We’re Young.” The group disbanded after the 90s, but the history of Mandopop girl groups did not stop there. Just a few years before S.H.E’s debut, Walkie Talkie, composed of Sara Yu and Fiona Huang, became a brief sensation with a series of songs celebrating sisterhood. Their first album, More than a Bond of Love between Sisters, in some ways anticipated the cultural significance of S.H.E. “Are you cold now?” the girls sing in the eponymous single, “let me warm you with my hands…dry your tears in my arms.” In their friendship anthem, “We Will Still Be Together Tomorrow,” the group further cements the importance of female relationship. “If you want to get a flash marriage one day, please get me a good man first so we could be happy at the same time,” they sing, “we will still be together tomorrow no matter where we are.” Interestingly, while men are not entirely absent from their songs, they only serve as the medium through which women bond with each other. It is, in a reverse Sedgwickian way, a story between women.

It was the exact story that S.H.E carried on after the 2000s. Walkie Talkie released their fifth and final album, Fairview Romance II, in the summer of 2001. Immediately following their disbandment, S.H.E came to the music scene with their first single, “Not Yet Lovers.” Lyrically, the song is not different from other ballads lamenting the ambivalent state of love. “More than friends but not yet lovers,” the girls sing, “I would run away with you if you dare to approach.” But in a way that later became their signature, S.H.E transformed the meanings of the lyrics and turned them from a story about heterosexual courtship into a tale of female homosocial love. The song, after all, is sung by three girls who live together, fall in love together, and share their most intimate life with one another. Rather than being the center of attention, the unnamed love object in the song is but a circuit that keeps the triangular desire of the girls running. This is why, paradoxically, the more the girls sing about their unrequited love, the more homoerotic the song becomes. The (supposedly) heterosexual love object does not negate the girls’ “homosocial desire” — to borrow Eve Sedgwick’s term — rather, it produces such a desire in the first place. In the end, it is impossible to tell whether the real love object is a boy or a girl. While “not yet lovers,” do the girls not mean “more than friends” to each other? This very ambiguity between heterosexual love and homosocial desire would run through S.H.E’s entire oeuvre. While the majority of their songs could be classified as love ballads, the girls turned them into homosocial anthems where a love interest, be it a boy or a girl, acts as the channel through which female homosocial desire flows.

With “Not Yet Lovers,” S.H.E became an overnight sensation. Following Girl’s Dorm, they released a series of successful albums in the 2000s. Unlike most girl groups in the western world, whose members often went on solo careers after initial success, S.H.E stuck with each other and continued to sing about female homosocial love. In fact, they developed the homosocial theme even further after their first album. Girl’s Dorm remained the only album that featured solo songs by individual members of the group. Since Youth Society, all of their songs were sung collectively — with ever more complex, ever more elaborate harmonies. Thematically, they also started exploring the multifaceted nature of female relationship. In “Message of Happiness,” for instance, S.H.E celebrates a girl friend’s newfound happiness. “I am happy that you could be happy first,” they sing, “next time you would be drunk in love with me.” Notably, the song continues the theme developed in Walkie Talkie’s “We Will Still Be Together Tomorrow,” in which a friend’s happiness symbolizes not the importance of men but the significance of female bonding. In “Nothing Ever Changes,” S.H.E sings about departure. “Hey, don’t be sad. I am not really leaving,” they console the unnamed lover, “I will remain the girl who loves you dearly when I am back.” While it was later revealed, at one of the concerts during their 2gether 4ever Tour, that the song was originally written for their parents, it could easily be translated into a tale about a female love lost and found. Significantly, it also explores loss, sorrow, and disappointment shared between women, which complicates the homosocial myth they have been making. The idea of female relationship as a journey was further developed in their 2004 song, “The Journey We Started Together.” “This is a secret journey that only belongs to us,” they proudly sing, “people would not understand our ecstasy but who cares? I only care about you.” In the accompanying music video, the girls are seen travelling in a scarlet car. While the car breaks down on their road trip, it only brings them closer to each other. It is, in many ways, a female road movie, a girly rendition of Thelma & Louise.

The female homosocial theme culminated in their 2007 classic, “Wife.” The song, written by Selina Jen and Ella Chen, foregrounds the inadequacy of the friendship motif and employs, instead, the metaphor of wifedom to define their relationship. “Friendship and sisterhood are not enough to describe our love,” they announce, “my wife, my wife, promise me to stay on the journey forever.” With “Wife,” the girls officially created an identity for themselves. Since the release of the song, they had frequently referred to each other as wives and the public followed suit. While Selina and Ella later went through marriage, divorce, and childrearing, their homosocial wifedom persisted in spite of the heterosexual rituals. These songs, from “Not Yet Lovers” to “Wife,” not only form an underground thread of female homosocial love across their albums but also document the evolution of such a love. They show both the multifaceted and evolving nature of female relationship. The girls could sing about happiness and loss. They could go from friends through lovers to wives. Their love to each other is not just complicated — they are also morphing. One song at a time.

S.H.E might have become another Walkie Talkie if they only sang about female relationship. A key element to their success came from the gendered differences between individual members, and how such differences contributed to the possibility of queer identifications. Early girl groups in the history of Mandopop often featured members who were vocally and stylistically similar. On the cover of their bestselling album, Live While We’re Young, City Girls wore the same red dresses, white stockings, and short haircuts. Other girl groups modified this tradition by including both short-haired and long-haired members. Walkie Talkie, for instance, emphasized the hairstyle differences between Sara Yu and Fiona Huang. However, while Fiona Huang became famous for her short hair, she was never explicitly butch. Vocally, Sara and Fiona also sounded similar to each other, leading to the illusion of their interchangeability. Such representations could of course be understood as queer, insofar as we consider how images of female narcissism are central to the history of lesbian iconography.

In an unprecedented way, S.H.E rewrote the history of Mandopop girl groups by featuring members who were vocally and stylistically butch and femme. Starting from their debut album, Ella Chen was presented as the butch member of the group. Vocally, Ella’s deep, mellow sound also contrasted sharply with Selina Jen and Hebe Tien’s feminine high notes. In early days, Ella often took up masculine roles due to her explicit butch quality. When Selina and Hebe transformed themselves into princesses on the cover of their fifth album, Magical Journey, Ella played the prince by wearing a silver suit. In the promotional image of their seventh album, Once upon a Time, Ella further complemented Selina’s barbie looks with her tawny jacket, white shirt, and black trousers. At one of the segments during their Moving Castle Tour, Ella appeared in a snow-white suit and referred to herself as a “piano prince.” After performing David Tao’s megahit, “I Love You,” Ella welcomed Selina and Hebe back to the stage and introduced them as “two beautiful princesses living in our castle.” Such a persona was further reinforced by a series of roles Ella had played in television dramas. The success of The Rose and Hanazakarino Kimitachihe both relied on the star image she had been building up since S.H.E’s debut. In the latter, she even played a girl who crossdresses in order to get into an all-boy school. It wasn’t until their 11th and possibly final album, Blossomy, that Ella gave up her butch role and started wearing long hair. By then, her butch performance was so successful that her feminine looks almost seemed like drag.

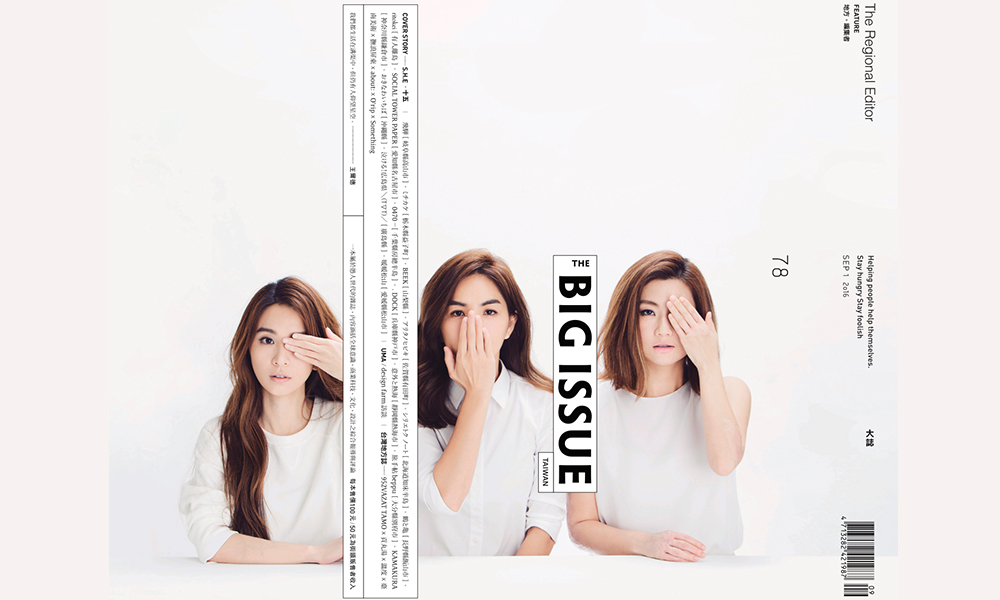

On the other hand, Selina and Hebe embodied conflicting yet complementary ideals of femininities. Upon their debut, Selina became famous for her hyper-femininity and was associated with the color pink. Her fragile, tender voice could be easily distinguished from Hebe’s powerful high notes. While it is tempting to see her hyper-femininity as a heteronormative performance, it would be more interesting to read it as a case of camp. It was overly stylized and sweetened, delicately ornamented and embellished. In the same promotional image of Once Upon a Time, for instance, Selina wore a dramatic blonde wig just as the doll she was holding. Rather than naturalizing her femininity, the wig turned her into a barbie figure and, in the eyes of gay men, a female drag queen. Compared to Selina’s hyper-femininity, Hebe had slowly but steadily developed a femme persona over the course of the group’s career. At first, the girls were less distinguishable from each other as they foregrounded Ella’s masculinity. Later, however, Hebe started to adopt a femme look with her signature bob. During the 2000s, bob was a hairstyle widely popular in the Taiwanese femme community. Hebe’s style evolution not only distinguished her from Selina but also, accidentally, turned her into a lesbian icon. Unlike Selina, Hebe had never been overly feminine. Her femininity was understated, toned-down, carefully mixed with a tinge of masculinity. Sitting beside Selina on the cover of Once Upon a Time, Hebe was seen wearing a white shirt, a beige corset, and — notably — a pair of brown breeches. She emerged, accordingly, as a femme figure around Selina’s barbie character and Ella’s butch persona. Both Selina and Hebe’s femininities, therefore, could be seen as potentially queer, albeit through different lenses.

The girls’ varying gender performances not only turned them into distinctive personalities but also created spaces for queer identifications. Their gendered personas, after all, were mutually constitutive. Ella’s butch character was shaped by Selina and Hebe’s femme sensibilities, while her masculinity, in return, highlighted their feminine mystiques. The interdependent nature of their star images rendered a myriad of queer relations possible. Ella’s playful flirtation with the girls, for instance, could be read as a butch-femme seduction scene, while Selina and Hebe’s intimacy could stand for an ideal of femme-femme love. It was exactly these possibilities that made them queer icons for the millennial generation in Taiwan. The queer millennials were able to identify with S.H.E not because they were gay per se, but because, through their gender performances, they came to embody queer relationalities. A queer identification with S.H.E did not rely on identity politics. It was, instead, based on a yearning for kinship outside the heterosexual norm. This was why gay men, lesbians, and straight girls could take equal pleasure in identifying themselves with S.H.E. A gay boy might enter the female community through becoming the Ella of the group. A lesbian could take up either Ella’s butch role or Hebe’s femme persona, and sometimes both at once. A straight girl could of course emulate the intimacy between the girls with her own friends. With the homosocial myth they have created over the past two decades, S.H.E became, arguably, the only girl group in the history of Mandopop able to evoke such diverse and intersected forms of queer identifications. Their homosocial love remained an enduring cultural fantasy in the Chinese-speaking world, not despite, but because of, its mythical nature. It was a queertopia that we never arrived at but forever yearned for. It was, to put it in José Muñoz’s words, a “warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality.”

In 2019, Yi-Ho, Yu-Chieh, and I decided to hold a symbolic wedding and become each other’s “wives.” Like S.H.E, Yi-Ho and Yu-Chieh have each experienced marriage and childrearing; like S.H.E, our friendship persisted nonetheless. On the evening before our wedding photoshoot, we reunited at a café in Taipei and went through the details for the next day. It was then that Yi-Ho proposed to create a secret code for our friendship, and it did not take long for us to realize what had been virtually decided 20 years ago on the afternoon of autumn rain.

The Eye. The Nose. The Mouth.

Photo Credit: The Big Issue Taiwan