Excerpt from Rainer on Film: Thirty Years of Film Writing in a Turbulent and Transformative Era (Santa Monica Press 2013).

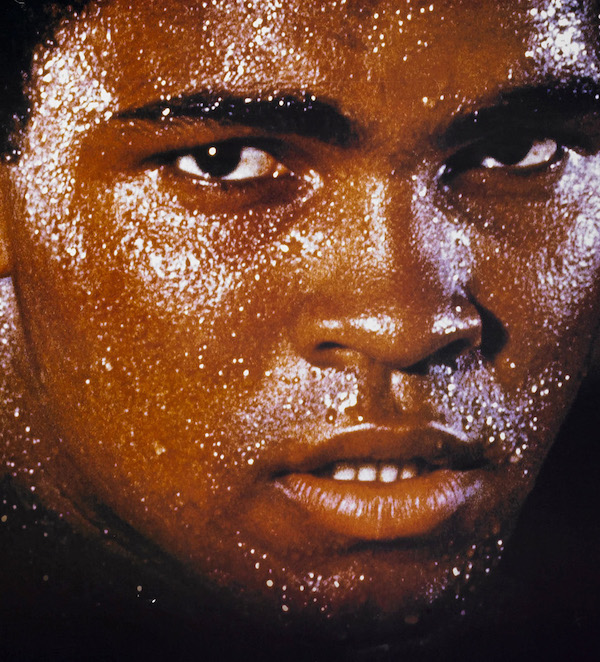

IN NORMAN MAILER’S The Fight, his great book on the Muhammad Ali/George Foreman “Rumble in the Jungle,” he begins by writing of Ali, “There is always the shock in seeing him again. Not live as in television but standing before you, looking his best. Then the World’s Greatest Athlete is in danger of being our most beautful man, and the vocabulary of Camp is doomed to appear. Women draw an audible breath. Men look down. They are reminded again of their lack of worth.”

This may sound like hyperbole but Mailer — like Ali — lives in the region where hyperbole can be transcendent. (It can also be bull). Mailer’s response to Ali in this passage is also our response to seeing him in When We Were Kings, Leon Gast’s amazing documentary about the 1974 Zaire fight and the events surrounding it. The film is unabashed hero-worship, but Ali is so clearly a hero here that we don’t feel swept away by gush. And because of what Ali has become — and George Foreman, too, with his newfound cuddliness — the movie is doubly poignant now. The documentary is, in essence, not much more than a record of what happened in Zaire, but it has been assembled with real feeling for the historical moment. It’s literally a blast from the past.

It’s also something of a miracle because it almost didn’t get made. Gast, who had already directed documentaries about the Hell’s Angels and the Grateful Dead, was initially hired to film the musical festivities surrounding the fight. He had in mind an African-American Woodstock complete with James Brown, B. B. King, the Jazz Crusaders, Bill Withers, the Spinners. Then, four days before the fight was scheduled, a cut to Foreman’s eye during a sparring session postponed the match for six weeks. Gast ended up training his cameras on Ali for much of that time, and what he came up with is the core of this movie.

It took almost 23 years to assemble. Returning broke from Zaire with 300,000 feet of celluloid — about a hundred hours — Gast spent the next 15 years processing portions of the film as he was able to pay for it. After finally untangling legal rights and acquiring completion funds, Gast and his newfound partner, David Sonenberg, an influential music talent manager, made the decision to insert additional fight footage and archival clips. They brought in Taylor Hackford to shoot and edit into the film look-back interviews with, among others, Mailer and George Plimpton and Ali biographer Thomas Hauser.

Gast includes snatches of the musicians doing their thing, but for the most part When We Were Kings is a musical in form far more than in content. It’s shaped like a musical — an opera, really — with arias of exhortation, massed choruses, and pomp. Gast knows how to syncopate the story; he gives it a pulse that finally makes it seem like the whole cavalcade of hype and holler is once again upon us.

Of course, we know how it all turned out: Ali, game but somewhat past his prime, stunned the world by knocking out the man most believed would demolish him. Gast builds our knowledge of the fight’s outcome into the film’s structure; there’s a retrospective thrill in seeing how hot the tumult got. It’s easy to forget now how geniune was the fear that Ali might be killed in the ring.

It’s the fear that underscores everything we see — the interviews with the sports commentators and trainers and fight organizers, with Ali’s giddy multitudinous African fans and even a worrywart Howard Cosell, who hyperbolizes about his concerns for Ali’s safety. Mailer makes the point during an interview that Ali must have recognized in his most private moments that Foreman could pulverize him, and the perception lends an extra dimension to Ali’s almost hysterical rants again his challenger. He takes up the African cry Ali boma ye — which means “Ali, kill him” — and is so rapturously insistent in leading the charge that the effect is frightening. It’s as if Ali were exorcising his own horrors right before our eyes.

Ali was attuned in a way Foreman wasn’t to the political momentousness of the event. “From slave ship to championship” was how he billed the fight, and his back-to-Africa oratory resonated with the Zaireans, who revered him not so much because he was a great fighter but because he stood up to the American government and refused induction into the Vietnam War. “No Vietcong ever called me nigger” was his mantra in all those years, and it made him a champion’s champion for people who sized up the racist implications of that war.

Ali had to demonize Foreman in the eyes of Africans; it was his standard operating procedure to run down his opponents before any fight. But Ali was faced with a problem in Zaire: In a match between two great black boxers in the “homeland,” how do you play up the racial angle? Ali was in fact much lighter-skinned that Foreman, but he castigates him as, in effect, white. “He’s in my country,” Ali says of Foreman, who had the misfortune to arrive in Zaire with his German shepherd — the very dog used by the Belgians to police the Congo.

Throughout When We Were Kings Ali comes on like — in Gast’s words — the Original Rapper. He successfully bleaches Foreman with his patter; he milks the press, the trainers, the camera crew. He says, “I’m not fighting for me, I’m fighting for black people who have no future.” Ali is not only a boxer of genius, he’s a politician of genius. I remembered being baffled by how wooden he was playing himself in “The Greatest.” But Ali — who has as much charisma as any movie star who ever lived — can come alive only by his own wit and instinct. To play a role in a movie, even if the role is himself, would mummify his genie.

When Ali lit the Olympic torch in Atlanta and we saw up close the effects of his Parkinson’s disease, the press covered the moment as if it were an unalloyed triumph. The commentators didn’t allow for our mixed emotions, our rage even, for what Ali had become — possibly owing in large measure to his having taken so many blows to the head from such fighters as George Foreman while we cheered him on. Ali is a hero still, but in a more complicated way. His presence is both an inspiration and an admonition. When We Were Kings brings back the unimpeded joy we once felt in Ali’s presence. It’s a movie in a state of denial — magnificent, unapologetic denial.

(1997)