By Mimi Zeiger

In 1990, several years before the San Francisco Museum of Art (SFMOMA) would move into its new building on Third Street, William Gibson wrote the short story “Skinner’s Room” for the architecture exhibition Visionary San Francisco. Commissioned by the museum’s first architecture and design curator Paolo Polledri, Gibson’s sci-fi dystopia depicted the city’s homeless population squatting on a defunct Bay Bridge while wealthy urbanites made their homes in 60-storey solar-powered towers.

Accompanying the text were illustrations by Los Angeles-based architects Hodgetts + Fung — sketches that made logic out of Gibson’s high-tech visions of a shanty town lodged in the bridge’s trusses and girders.

True to the aphorism often attributed to Gibson — the future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed. The city, boosted by Silicon Valley wealth, is seeing a kind of hyper-renewal as companies like Twitter and Airbnb revamp disused office buildings along Market Street. Skyscrapers perched on Rincon Hill loom over the bridge, providing luxury residences for S.F.’s tech elite, while freeway overpasses shelter homeless encampments.

This past spring, SFMOMA re-opened its doors with a 235,000-square-foot addition to Swiss architect Mario Botta’s brick-clad edifice. Architecture firm Snøhetta, which has offices across the globe, including Oslo, New York, and San Francisco, designed an expansion that more than doubled the overall size of the museum and nearly tripled the gallery space.

Art museums play a particularly hybrid role in today’s cities; curators and education (and marketing) departments alike spin narratives of community engagement while executive leadership courts the pocketbooks of urban elite. While this dynamic isn’t entirely new, its accompanying architectural tropes were codified by the global museum building boom in the years since Botta’s design: expansive public lobbies, education wings, and event spaces. Snøhetta’s scheme attempts to bridge these dual purposes endemic to art institutions while adding a new revised icon to the skyline.

The new all-white façade dominates the original building. Made up of 700 custom fiberglass panels, it was supposedly inspired by the city’s legendary fog. But it looks more like an iceberg caught in San Francisco’s urban fabric. While the dense site demanded a more vertical solution — the museum was constrained by existing buildings — the scheme also suggests that the city (not simply the museum) is orienting in a different direction: upwards. There’s a dozen high rises built, in construction, or proposed for the nearby Transbay District, including works by international architects Jeanne Gang, Norman Foster, and Rem Koolhaas. At 61-storeys and 1,070 feet, Pelli Clark Pelli’s Salesforce Tower will be the tallest building in San Francisco.

The new design repositions SFMOMA, literally turning the orientation of the building around to face the Transbay District. Long terraces skirt along the east façade of Snøhetta’s addition. Perfect for donor cocktail events and member parties, they overlook S.F.’s present and future development.

Meanwhile, Botta’s original postmodern SFMOMA remains as an appendage to the new structure. Squat and striped, it trades in a kind of symmetry that was out of fashion by the time it opened in 1995. Still, the architecture achieves a strange mid-rise contexualism with Yerba Buena Gardens and the Moscone Center across Third Street. Both the Yerba Buena Esplanade, with its adjacent cultural and commercial spaces, and the convention center were part of an urban redevelopment scheme for South of Market that had been underway since the late 1950s.

In 1967, a master plan for Yerba Buena Center, a dense mixed-use commercial district, was created. Over the next three decades implementation began, halted, and was restarted incrementally. For years, the site across from SFMOMA — the gardens, Metreon shopping mall, and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (YBCA) — was a giant parking lot, the result of gung-ho bulldozing. Like Los Angeles and so many other cities across the United States in the second half of the twentieth century, San Francisco was incentivized by city agencies to clear its slums. Los Angeles razed Bunker Hill, while the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency knocked down boarding houses and SROs around the Yerba Buena site, thus displacing some 4,000 low-income residents.

The seventies and eighties were marked by recurring fights between tenant groups and planners. By the early to mid-1990s, the low-profile and pavilion-like architecture of the buildings that had gone up — such as SFMOMA, Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki’s YBCA galleries, and the theater by Polshek Partnership (now Ennead) — were tepid attempts to repair the urban fabric.

While its unfair to hold arts institutions responsible for San Francisco’s crisis-levels of homelessness, the systematic demolition of low-income housing (however marginal) and the inability of the city to keep pace with affordability adds a dark edge to SFMOMA’s expansionist narrative and the continued development of South of Market as a cultural hub. Indeed, this near-intractable relationship is illustrated by the Mexican Museum on Mission Street, kitty-corner to SFMOMA.

This past July, the Mexican Museum held a “family-friendly Dedication Ceremony & Cornerstone Presentation” for the building, which was designed by Enrique Norten of TEN Arquitectos. The museum occupies the first five floors of a 53-storey luxury condo and office tower. According to the San Francisco Business Times, the developers, Millennium Partners, will contribute a $5-million gift toward the museum endowment, as well as an additional $5 million to S.F.’s affordable housing fund— a gesture towards housing elsewhere in the city. The tower itself includes no affordable units. While Proposition K passed by San Francisco voters in 2014 requires a percentage of affordable units in multifamily projects built on public land, the $500-million project was entitled earlier and is under thus no obligation to meet such criteria.

Architect and Snøhetta founding partner Craig Dykers appears aware of the area’s latent and not-so latent history. “When Mario Botta was designing SFMOMA in the early to mid-1990s, the area south of Market Street known as SOMA was neglected and residual to the city,” he writes in an email, noting that Botta placed the museum entrance on Third Street, a thoroughfare connecting SOMA to commercial Market Street. “This was the right decision at the time,” he writes, “and helped propel the area into the thriving neighborhood it is today.” He suggests that his firm’s expansion connects into the smaller lanes and alleyways tucked behind many of the grander building that face the major streets. It’s a more subtle approach to urbanism than the earlier redevelopment plan: “In the near future, you will see more and more people walking along these laneways framed by historical buildings in the neighborhood rather than only using the avenues defined by newer towers. The new SFMOMA will have spearheaded this trend.”

Snøhetta’s expansion includes a new entrance on Howard Street, around the corner from the original. There, on a busy street that until recently had largely been ignored by urban renewal efforts, the museum greets visitors with a glass storefront. In the shop window sits Richard Serra’s massive steel sculpture, and behind it a new grand staircase rises to a second floor ticketing area. It’s a dramatic display of museo-might, the pairing of monumental architecture with monumental art. And, according to Dykers, a democratic gesture toward the city.

SFMOMA’s dual lobbies are part of a larger pedestrian pathway that cuts through the museum. Public spaces on the ground and second floors are free and open an hour before the galleries. Snøhetta removed Botta’s granite staircase and replaced it with a more functional wood and steel construct. Dyker’s suggests that the openness reflects the tech culture’s ideals of connectivity and access. “It’s possible to walk from one entry to the other and view works by Serra, Sol Lewitt, Alexander Calder, Mark Bradford, and Matthew Barney without purchasing a ticket,” he says. “The notion of enabling social interaction, sharing and barrier removal found in Silicon Valley is at the core of the museum experience.”

Rather than reflecting the community, the expansion reflects major donors: Gap founders and philanthropists Doris and Donald Fisher and new media and digital art aficionados like Pamela and Richard Kramlich. 60,000-square feet of gallery space across three floors is dedicated to the Fisher’s postwar and contemporary collection, while the Kramlichs supported the 4,400-square foot Media Arts gallery on the seventh floor.

In August, reporting for the San Francisco Chronicle, art critic Charles Desmarais dove into a deal between the Fisher’s and SFMOMA that enabled the museum expansion — a deal carefully shrouded from public view and light on details. 260 of some 835 works from the Fisher collection are on view in the fourth, fifth, and sixth floor galleries. In his August 20 article “Unraveling SFMOMA’s deal for the Fisher collection”, Desmarais is critical of how a single collection dictates close to “60 percent of SFMOMA’s indoor galleries,” minus the lobby and public areas. He writes, “Unlike in other spaces designated to honor big donors, which might hold a range of different works and exhibitions, the Doris and Donald Fisher Collection Galleries are required to contain primarily Fisher works at all times. No more than 25 percent of what is on view may come from other lenders or donors.”

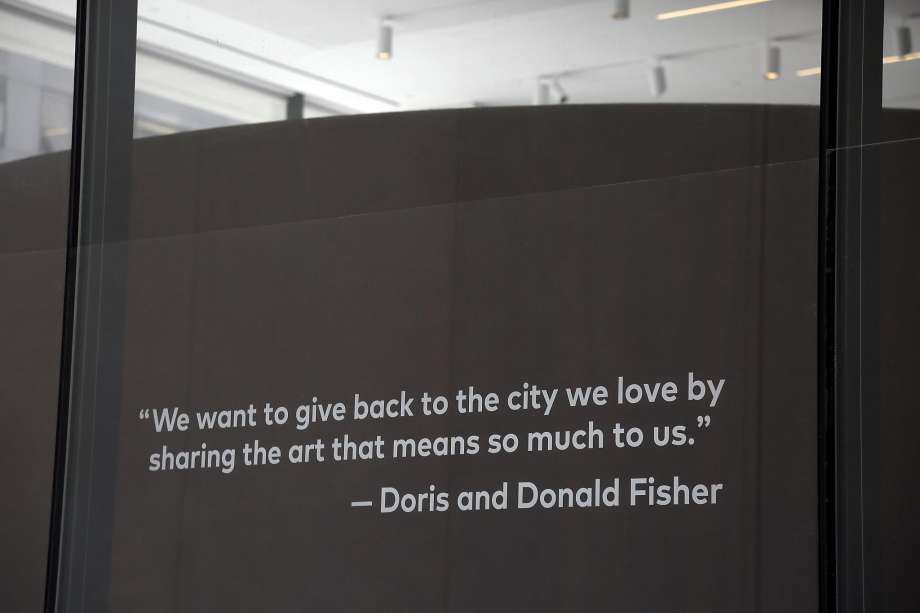

Desmarais’s article was illustrated by a photograph, taken by Eric Risberg of the Associated Press, of the glass storefront near SFMOMA’s Howard Street entrance, which bears a quote from Doris and Donald Fisher. The text reads, “We want to give back to a city we love by sharing the art that means so much to us.” Located at street level in direct view of pedestrians, citizens, and denizens, the words are meant to inspire camaraderie and common values. Yet as the city and the museum stretch upward, as homeless encampments cluster under the overpasses leading to the Bay Bridge, the language of sharing rings hollow.

Mimi Zeiger is a Los Angeles-based critic, editor, and curator. She has covered art, architecture, urbanism, and design for a number of publications including The New York Times, Domus, Architectural Review, and Architect, where she is a contributing editor. She is a regular opinion columnist for Dezeen and former West Coast Editor of The Architects Newspaper.