Alma Routsong was browsing through a folk art exhibit on a tour of upstate New York when she discovered a captivating image of a mermaid. When she got closer to this picture, she read the placard. It stated that the artist, Mary Ann Willson, lived and worked with her “farmerette” in Greenville Town, Greene County, New York, circa 1820. Routsong then went into another room and found a book that explained that Willson’s “farmerette,” who we only know as “Miss Brundidge,” had a “romantic attachment” with Willson. Stunned by the story of two nineteenth-century women lovers, Routsong didn’t care about the rest of her tour of upstate New York. “I didn’t want to see Harriet Tubman’s bed,” she later recalled. “I wanted to go home and research Willson and Brundidge.”

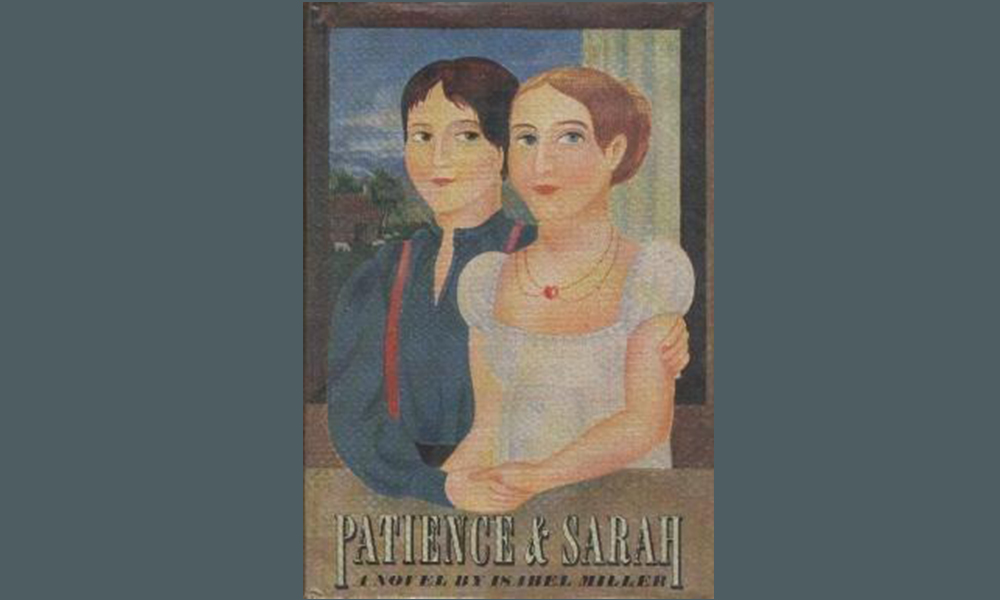

At 41 years old, Routsong had divorced her husband, given birth to four daughters, published two novels, and was in a relationship with another woman. But even in the mid-1960s representations of lesbians were scarce. The mere hint of a lesbian relationship, let alone one from the early 19th century, inspired her to find whatever details about Willson and Brundidge that she could. She spent a year researching the couple — going to local libraries, poring over census records and city directories in the genealogical room at the New York Public Library — but found nothing. So she turned to fiction. She imagined histories of Willson and Brundidge, wrote them in a novel, and self-published it as a Place for Us about the mysterious couple. In 1972, McGraw-Hill bought the novel and changed its title to the protagonists’ names, Patience and Sarah.

Routsong, however, was not alone in her fascination with these obscure queer figures in history. As the campaigns for gay liberation escalated in the 1960s — culminating with the Stonewall uprising in 1969 — many LGBT people turned to the past for inspiration. Uncovering stories from history helped them develop a cultural heritage and also enabled them to make their identity legible. Gay newspapers continually featured stories on writers, poets, and artists who were long dead but were rumored to be LGBT. The Body Politic, a gay newspaper that ran in Toronto from 1971 to 1987 and enjoyed a huge readership across the United States, devoted a special section, “Our Image,” to both reviewing the uptick in representations of gay people and uncovering “our lost history.”

In 1977, Michael Lynch, who taught the first gay studies course in Canada at the University of Toronto, wrote a compelling portrait of the infamous American painter Marsden Hartley; he noted that 1977 marked the centenary of Marsden Hartley’s birth in Maine in 1877. In the article, “A Gay World After All,” Lynch uncovers Hartley’s gay life and examines how his sexual identity shaped his art.

Despite attending art school in New York City in 1899, Hartley’s “introduction to a living gay tradition,” according to Lynch, “seems to have come not in Greenwich Village but in Maine.” In 1905, Hartley met a group of “Whitman admirers” who he “quickly grew close to.” One of the men included William Sloan Kennedy who gave Hartley a signed portrait of Whitman, which Whitman had given to Kennedy before he died.

At the turn of the century, the past was not even the past. The portrait was not the only connection that Hartley had to Whitman. He even managed to track down Whitman’s former lover, Peter Doyle, who was in sixties and “reticent” to talk about Whitman. Despite the silence, Hartley was so inspired by evocations of Whitman’s same-sex relationships that he shifted gears from painting and wrote “two prose sketches” about Whitman. According to Lynch, Hartley treated Whitman like a “Lover God.”

Hartley’s adoration for finding other men in history who were rumored to be queer continued. Hartley wrote two poems about Abraham Lincoln, fixating on Lincoln’s “woman’s lower lip … upon his man’s upper.” Lincoln’s face, Hartley confessed, “is the one great face for me and I never tire looking at. I am simply dead in love with that man,” he wrote. Lincoln served as an inspiration for two of Hartley’s poems and three of his paintings. Writing about Lincoln and Whitman and painting portraits about them enabled Harley to connect to iconic queer people from the past.

Lynch’s recovery of Hartley and Hartley’s recovery of Whitman (and Lincoln) illustrates the persistence among LGBT people to reject the prejudicial assumption of gay identity as new and uncommon and instead to anchor their identity in the past. The rise of gay liberation gave way to a renaissance in queer literature in 1970s. Within months of the publication of Lynch’s story of Hartley in The Body Politic, the December 1, 1976 issue reviewed three biographies of Oscar Wilde, all published by top-tier commercial presses. Publishers wanted to capitalize on what seemed to be a new market in gay literature.

The Body Politic, however, remained suspicious of mainstream’s publishing industry’s fascination with gay subjects. It was one thing for gay people to search for icons in the past. It was quite another for straight people to do it. In December 1976, the noted lesbian novelist Jane Rule reviewed three books on queer women writers — George Sand, Amy Lowell, and Carson McCullers — for The Body Politic. Rule eviscerates each biographer for failing to properly treat their subject’s gender and sexual identity. She notes how George Sand’s biographer overlooks intimate relationships she had with women in her life; she claims that Sands’ male biographer, Curtis Cate, centers “sexual and maternal love” as the only relations that mattered in Sand’s life. Rule also reports on how McCullers’ biographer “rebuffed” McCullers’ infatuation with a range of queer icons from Greta Garbo to Katherine Ann Porter. According to Rule, McCullers worshipped these women not only because she preferred “to be lover rather than to be beloved” but also because it meant that McCullers saw herself as “a young genius” worthy of worshipping these icons. Rule further indicts Lowell’s biographer for suggesting that her intimate relationships with women later in her life resulted from “unrequited heterosexual love.”

Publishing in The Body Politic enabled Rule to respond to the homophobia and sexism that queer people had previously whispered about in private or only among themselves. Rule interrupts her review essay in order to accentuate how the rise of gay liberation had led to a change in sexual mores and the opportunity for biographers and readers to think more carefully about sexuality in both the past and the present. “The relatively new freedom of biographers to discuss the sexual nature and experience of their subjects should be welcomed,” Rule explains, “but, as Body Politic, by its very title, suggests, neither genitalia nor sexual acts in themselves can, in insolation, tell us much about the person whose total identity and experience are involved.”

This is Rule’s windup for her final takedown of Sand’s biographer, who went to great lengths to prove that Sand did not have an intimate and sexual relationship with actress, Marie Dorval. Cate also believed it was his duty to disabuse the public that Sands would have been supportive of women’s liberation and thereby should not be recovered from the past as a queer historical figure. Rule fired back: “The point is not that George Sand was a lesbian or a women’s libber. Her life has been taken into the hands of a biographer who wants to dominate her as no man in her life had been able to.”

While Rule remains protective of these queer women’s identities and reputations, she does not romanticize them. She recognized that Sand’s and Lowell’s class status enabled them to cultivate their literary crafts. It also protected them from discrimination and prejudice. While many in the 1970s were quick to recuperate these queer figures as forgotten icons, Rule was more careful and thoughtful in her assessment of their contributions.

While Rule did recognize Sand’s and Lowell’s class status, she did not, however, point out that they were both white. While this certainly indicates the rampant racist currents within the LGBT community at the time, not all writers viewed the past through a lily-white lens. Jonathan Ned Katz, who published the first anthology of primary sources about LGBT people, Gay American History, in 1976 searched for inspiration in the archives and uncovered both white and black people.

While The Body Politic recovered stories of queer writers and artists from the past, not all LGBT people turned to literature for inspiration. While Routsong joked that she did not want to see Harriet Tubman’s bed, intersectional black feminists organized a collective in 1977 and named it the “Combahee River Collective” after Tubman’s legendary liberation of enslaved people near the Combahee River.

Meanwhile, black inmates in Indiana state prison evoked the 1857 Supreme Court case of Dred Scott to appeal the conviction of a gay prisoner. Join Hands, a gay prisoners’ newspaper founded in San Francisco in 1972, published the appeal by black inmates who called on readers for support due to an accusation that “a gay black inmate,” Valgene Royal, slayed a white laundry supervisor. According to their testimony, Royal was in his cell during the time of the murder. But, they argued, since he was “a homosexual” and “feminine,” the prison officials accused him of the murder. They ended their appeal by citing the landmark Dred Scott decision and asserted “that no black man has a right that any white may uphold, or respect.”

Fifty years ago, LGBT writers, artists, and activists turned to the past for inspiration. They found evidence of people who served as their predecessors. As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of Stonewall this June, many LGBT people can now consider that the past is, in the words of Alma Routsong, “a place for us.”

Jim Downs is Professor of History and Director of American Studies at Connecticut College. He is the author of Stand By Me: The Forgotten History of Gay Liberation.