By Sara Lipton

President Trump’s recently completed overseas tour has left pundits struggling to explain his surprising affinity for the pre-modern Saudi Arabian monarchy. This hardly seems the attitude of a populist, a Christian conservative, or an ethnic nationalist, to mention just three of the labels that have been applied to him. Rather, the president’s preferences suggest that we should look further back than the 20th century to understand his political style and impulses.

Trump is a Merovingian, a near-perfect reincarnation of an early medieval Germanic king. His personality and approach to governing almost exactly replicate the patterns and preferences of the men who ruled France from 481 until 752, descendants of the warrior-made-king of the Franks known as Clovis the Merovingian.

Trump’s personal style and family life have a distinctly early medieval monarchical aura. President Trump’s penchant for bragging has amused (and bemused) commentators and generated headlines, but early medieval observers would not have raised an eyebrow — modesty had no place at the Merovingian court. Clovis was wont to “boast in a childish way” of his untrammeled power: “fate has made me heir to the entire country […] I can do to [my enemies] whatever I choose.” The chronicler Gregory of Tours tells us that “King Chilperic used to maintain that no one was cleverer than he.” (Gregory also observed in despair that, like many a Trumpian pronouncement, “Chilperic’s poems observed none of the accepted rules of prosody.”)

Like the current resident of the White House, Merovingian kings had rather messy love lives. They tended to alternate between foreign-born princesses, who lent sophistication to the court, and lowborn subjects, who could be raised up and cast off at will. In one somewhat dizzying chapter, Gregory of Tours lays out the marital history of King Charibert. He first married a woman called Ingoberg. But he soon “fell violently in love” with two of her servants, the daughters of a poor man. Dismissing Ingoberg, he married one of these sisters, Merofled. He soon had a child together with another woman, the daughter of a shepherd, before proceeding to marry Merofled’s sister. Gregory tells us that Charibert was excommunicated for this last marriage and died soon after. The implication of the comment is that the king’s sins finally caught up with him, but it’s hard not to suspect that his energy simply gave out.

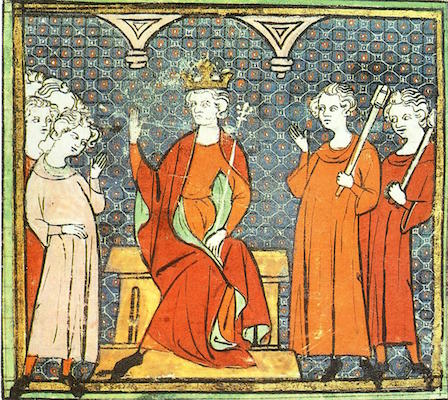

Although stories of Trump’s gold-plated toilet have been debunked, his taste in furniture clearly veers toward regal gilt. Many kings, of course, embrace ostentation, but golden thrones were particularly popular with the Merovingians. Saint Eligius, a provincial boy trained as a goldsmith, found fame and fortune when King Clothar “wanted a seat urbanely made with gold and gems, but [found] no one […] in his palace who could do the work as he conceived it.” (Unlike his modern counterpart, however, Clothar did not quibble with his contractors: “The king began to marvel and praise such elegant work and ordered that the craftsman be paid in a manner worthy of his labor.”)

And then there’s Trump’s unusual hairdo. Unlike captains of industry, who tend to adopt standard and unobtrusive garments and grooming, kings like to stand out. The Merovingians were known as the “long-haired kings” because, alone among their fellow Franks, they did not cut their hair. Long hair consequently became a sign of royalty and power. When King Childebert grew concerned that his brother’s sons might pose a threat, he mused, “Ought we to cut off their hair and so reduce them to the status of ordinary individuals?”

Recognizing the essentially pre-modern, dynastic nature of Trumpian power helps us to understand his apparently idiosyncratic style of governing.

Early medieval kings took a pragmatic approach to religion, to say the least. Clovis, the pagan-born founder of the royal line, vowed to become Christian if he were victorious in an important battle. He did indeed win the battle and convert, ostensibly convinced of the divinity of Christ. But historians suspect that the support of the powerful Catholic clergy, and the fact that the residents of a region he hoped to conquer were majority Catholic, were equally weighty spurs for his new-found faith.

Many analysts expected that Trump, our first television-star, real-estate developer president, would shift his attention to more serious issues upon assuming office. But many an early medieval ruler recognized the political value of entertainment and splashy building projects. During a particularly tense moment in his reign, King Chilperic ignored the threats of a neighboring king in order to construct amphitheaters in two key cities, as he was “keen to offer spectacles to the citizens.”

Although no previous presidential daughter has wielded the kind of power enjoyed by Ivanka Trump, in Merovingian Francia female members of a royal dynasty could play significant political roles. When King Childebert was summoned by a neighboring king to an urgent meeting on public business, he “took his mother, sister, and wife with him.” Princess Clotild, a nun who had her own private army, commanded great wealth, and remained politically active, organized a rebellion at her own nunnery. She personally directed the fighting, stood her ground in front of a tribunal of bishops, and then refused to return to her nunnery when ordered, retiring instead to an estate given to her by her father the king.

Finally, the power dynamics of Merovingian courts are precisely replicated in the ostentatiously public dinner-table diplomacy conducted at Mar-a-Lago, the calculated manipulation of invitations to dine with the president, and the rivalries and jockeying for closeness to Trump that seem to characterize his inner circle. The Germanic title of “table-companion” was reserved for the king’s favored friends and military and political allies. In his History of the Franks Gregory of Tours several times tells us who ate dinner with the king, as a sure-fire indication of who was “in” and who was “out.” Even though the biographer of the saintly Eligius set out to praise an unworldly man of God, he actually gives us a portrait of a powerful politician and lobbyist, noting that Eligius was “granted such familiarity [by King Dagobert] that his happiness earned the hatred of many,” and that “his fame spread abroad so that Roman, Italian, or Gothic […] would not go first to the King, but would repair first to Eligius.”

Does Trump’s mastery of the art of Merovingian rule mean that we are doomed to 271 years of Trump family dominance? Not necessarily! The administration’s apparent lack of legislative achievement bodes ill for his dynastic longevity. The later Merovingians, who could boast little in the way of accomplishments, became known as the “do-nothing kings.” They were consequently deposed by another ambitious, and more effective, family. Chelsea Clinton, Andrew Cuomo, or Jeb Bush, take heart!