“Dinner here is 8:30, so arriving at Saint Ellero before 8 is ideal,” Andy had written in an e-mail and when I got off a Trenitalia carriage on the second day of June this year, he was standing by the rails to greet me, as promised. Andy (Andrew Sean Greer, for those who know him from his novels) had driven to the station in a small rented car. As we rode through the steep roads curving through Tuscan mountains, the San Francisco-born novelist happily reported the recent change in the weather of Reggello: summer had finally arrived. I watched the brightly illuminated green woods and distant mountains from the windshield, as Andy told me about his life in Tuscany, and his latest novel, Less, which The New Yorker would run an excerpt from in its upcoming issue. Before moving to the next subject, the political tribulations in my home country, Turkey, the road curved to Donnini, the little Tuscan town where Andy proposed to stop by at a bar to drink some aperols before heading to our real destination.

Around a metal table outside the bar, where Andy apparently has killed time while waiting for my arrival, sat Adam Foulds, the British novelist and Enrico Rotelli, the Italian journalist. Again, there were questions about Turkey and how life had been there lately. I suggested more local topics when the conversation shifted to the curiosities of Donnini. Among locals who surrounded us at the moment — chain smokers and drinkers of Peroni — the house we were about to visit had gained an almost mythical status, I learned. Santa Maddalena, “the retreat for writers and botanists” where I would spend the next six weeks, is inseparable from its equally mythical owner Baronessa Beatrice Monti della Corte von Rezzori. The baronessa, and her constantly changing court of writers, have long intrigued people’s minds here. I, too, felt slightly anxious about entering this alternate world where, as I would find out soon, people talked and practiced literature from breakfast to bedtime.

A bumpy dirt road brought us to the lawn covered front door behind which the baronessa was waiting, accompanied by her beloved pug, Rosina. She founded Santa Maddalena in 2000, to continue the tradition of hospitality shown to fellow writers and artists by her husband Gregor von Rezzori (or Grisha, as everyone continues to affectionately refer to him, 20 years after his death in 1998). The German language novelist is best known for his 1969 book Memoirs of an Anti-Semite; an extremely handsome man, he had turned heads of fellow actors Monica Vitti, Brigitte Bardot and Jeanne Moreau during his second career in art films. Every season, Beatrice and Andy, who runs the residency program, pick three writers (two during the festival) to host at the foundation for six weeks during which time maids clean their rooms and clothes and cooks serve them with examples of Neapolitan cuisine. Only two requirements are made from the fellows: show up at lunches and dinners at the main house in a decent outfit, and write — whatever you like.

After desserts, cigarettes, and red wine, I walked half drunk and completely exhausted from a long day of traveling, to the signal tower, located about three hundred meters away from the main house. Michael Cunningham wrote The Hours here, Zadie Smith worked on The Autograph Man in one of the building’s four stories, and Colm Tóibín found it an ideal place to begin The Master. This history, you see, puts some pressure on one’s shoulders. Atiq Rahimi, the Afghan-French novelist and filmmaker whom I met over dinner, would be my companion there. The wonderfully energetic man, who had the upper two stories, he was often to be found bound to his desk on the top floor, a work by Miró hanging on the wall.

The tower, surrounded by fireflies, was invisible in the darkness on my first night. The legend has it that the 13th century signal tower was used during the German occupation of Donnini in the second world war, to send messages to Allied Forces.

Every day began with breakfast on the stone table that Atiq and I nicknamed “the round table of Afghan and Turkish poets.” My fellow Tower resident, who won the Prix Goncourt for The Patience Stone in 2008, was busy working on his new novel. So engulfed in his work was he, that an invitation to a dinner party given by Emmanuel Macron had to be refused (Atiq feared the trip to Paris would slow down his writing). Cunningham had once talked about the magic of the Tower: once you get used to its atmosphere and start putting the words on paper, you don’t want to be brought away from it, even if it is the president who is summoning you.

Atiq and I spent weeks working on our novels (mine is a campus novel about two young people involved in a “digital romance”; his…well, you will soon find out). Every day was more or less the same: good morning Atiq, writing time, lunch, writing time, good night Atiq. We headed to the main house for lunch, walked back, met again before dinner for some house wine. We listened to Radio France in the mornings and John Zorn and Keith Jarrett at night.

By mid-June, our productive routine slightly changed, thanks to Festival degli Scrittori. Baronessa had been organizing this meticulously curated literary festival in Florence since 2006. Weeks before the opening ceremony I noticed, during lunches at Santa Maddalena, worried brows among the organizers: the Florence commune no longer supported the festival the way it had in the past; cuts to its funding meant the baronessa had to pay the lion’s share for the four-day long festival.

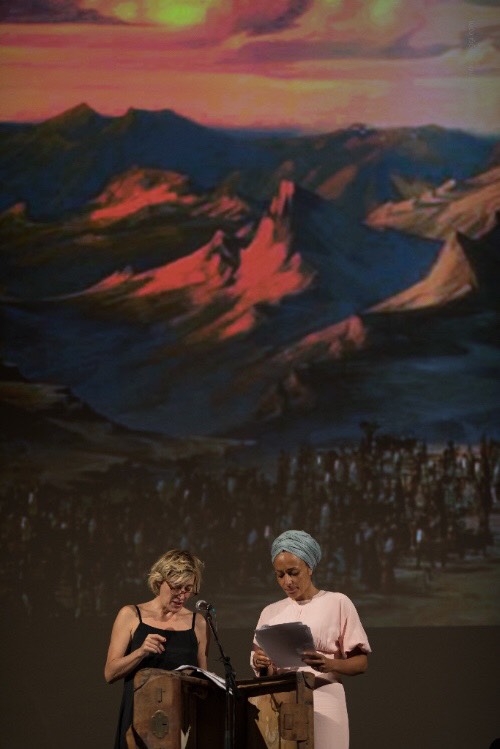

There were daily rides from Santa Maddalena to Florence. In the lobby of a city hotel for guest authors, I met Juan Gabriel Vásquez, the Colombian novelist who inquired about the state of Turkey. “Oh, let’s talk about books,” I said. Minutes later, Zadie Smith appeared at the entrance, and after a quick hello, disappeared into the staircase. Volker Schlöndorff came to the mansion for dinner with his wife and daughter who apparently grew up in the same village with Santa Maddalena. After dessert, the conversation circled around “The Empty Suitcase,” a performance Schlöndorff was scheduled to stage the next day at the Odeon Theatre. The German director, who has long owned a house near Santa Maddalena, assigned numerous texts (from the Odyssey to Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West) to a group of writers including Smith, Rahimi, and Vásquez, about immigration and the state of the downtrodden. To the background tune of chirps by crickets, Schlöndorff and baronessa, both perfectionists, elaborated on details.

Hisham Matar came the following day, passionately describing the horrors of the Grenfell Tower, located on the same street with his Notting Hill house. On the bumpy road to Florence, he asked me about the political situation in Turkey; in response, I told him about this great book I had been reading for the past week (The Red Haired Woman, the soon to be published in English novel by Turkish Nobelist Orhan Pamuk, a previous visitor of Santa Maddalena, I later learned). Land Rovers, packed with Pulitzer, Goncourt, and Booker winners, continued to shuttle between the silent grounds of Santa Maddalena and the tourist occupied streets of Florence, with views of travelers eating gelato in the background.

Inside the terrace of Palazzo Strozzi, Edmund White was chatting with Édouard Louis about The End of Eddy and his new book, The History of Violence, a contender for this year’s Premio Gregor von Rezzori. The prize, given to a work of fiction, is judged by baronessa and a group of her trusted friends. The sun was ruthless in its intensity, the wanderers of the city too eager to see all the things that surrounded them, and only a few seemed to take notice of the great authors wandering around their flag-carrying tour guides. László Krasznahorkai materialized the following day and chatted about how he loved Florence for all the works it hosts by Fra Angelico, for whom we share passion. On the other side of the street, in a small coffee, Mathias Énard sat chatting with his dear friend Atiq, who advised Énard to follow his Goncourt winning Compass with a book of non-fiction. (Atiq had written another novel after his award, a decision he ended up regretting; “the post-Goncourt expectation destroys you,” he mused. “Just write a book on books, and wait a few years for the new novel.”) Énard said this was excellent advice.

At night I returned from the crowded streets of Florence to my silent room at the Tower, its walls decorated with edicts by Ottoman sultans and their portraits, and engravings of Istanbul. Baronessa’s parents had been Istanbulites, working as official bankers for Ottoman sultans, and were forced to leave their glorious mansion by the Bosphorus during the mass killings of Ottoman Armenians in early 20th century, escaping first to Syria and then to Capri. In the darkness of the Oriental room, I listened to the distant sounds of bats and howling dogs, imagining the adventures of the Koceoglu family which I decided to investigate in detail upon my return to the city.

After Énard was announced as the winner of this year’s prize, the court of writers disbanded, following a late night drinking party at the main house. The baronessa’s new guest, Michael Cunningham, arrived the next week and for a while, the center of conversational gravity shifted from Paris to New York. There were affectionate lunchtime anecdotes about Barbara Epstein and Robert Silvers, dear friends of both Beatrice and Edmund White, and words of dismay about America’s ignorant commander-in-chief. Before going to sleep, Cunningham and I listened to Max Richter’s Three Worlds: Music from Woolf and I remembered the final scene of The Hours but kept silent.

Atiq left the Tower on the last day of June, as did Cunningham and White. Now Santa Maddalena was almost deserted but for Beatrice, me, and her staff. By the time Colm Tóibín arrived, I was the Tower’s sole resident. Baronessa seemed happy with her two guests, and for the rainy weather that finally arrived during a dry season for her town.

I spent my last day at Santa Maddalena behind the stone table, listening to music and smoking a rollie cigarette, under the shadow of the Tower. A cold wind blew from the distant mountains, and apart from that all was silent at Santa Maddalena. On my first day here, Andy had warned me that the fireflies would be gone after a few weeks — enjoy them while you can, he had said. They were indeed gone now and the place was stark dark but for the light of my iPhone which functioned as a digital candle in this timeless place. I thought about Turkey and the little apartment where I live in Istanbul, and my trip back home. The only thing the light illuminated were my hands. Before heading back to the Tower, I realized that they were the only thing that mattered, at the end of the day, and that I could still work for a few more hours.