By Mark Sarvas

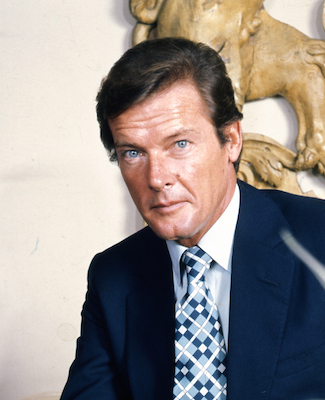

Roger Moore, who died this week at the age of 89 and played James Bond seven times, went head to head in 1983 against … another James Bond.

That summer saw the near simultaneous release of both the execrable Octopussy (Moore’s penultimate turn as 007) and the less-dreadful Never Say Never Again, which returned Sean Connery to the role that made him an international superstar. As far as the box office was concerned, the newer Bond got the better of that exchange. It may have been the only time the perennially underrated Moore triumphed over Connery.

Just as the rock world divides between Beatles people and Stones people, the world of James Bond divides between Connery people and Moore people, and the choice allows us to generalize about the chooser. The familiar broad strokes are: Connery was the tougher, truer Bond; 007 as Ian Fleming had intended. Moore was a bit of comic lightweight, not without charm but lacking gravitas, wisecracking in his predecessor’s long shadow. The other Bonds fall conveniently on either side of this fault line; Timothy Dalton and Daniel Craig can be considered Connery’s heirs, whereas Pierce Brosnan more or less follows in Moore’s tasseled footsteps.

My own allegiances are more complicated and began forming on a summer evening in 1973, when my Hungarian immigrant father — with whom I shared very little — dragged me out to the neighborhood movie theatre to see a film he was convinced I would love. My nine-year-old self was spellbound from the opening frames, as I watched a tall man walk across the screen, framed by a gun barrel. The man suddenly stopped, spun to face us, gun in hand, and fired. A red wash crept down the screen and I was forever altered. By the time Paul McCartney and Wings finished singing “Live and Let Die,” my initiation was complete. (A little bonus-level Bond trivia: Live and Let Die is the only film in which Bond does not appear at all in the pre-credits sequence, the producers shrewdly drawing out the reveal of the newly anointed Moore.)

Although that night in the theater was more than 40 years ago, I still see it with astonishing clarity. I returned to that same theatre at least three times that summer to relive the movie, to lose myself in this fantastic world. Looking back, the appeal is easy to see. I was a short kid, unathletic, picked on, unpopular. Here was this gliding, tall, refined hero. Women loved him, men feared him and he always, always knew just what to say. As a pre-teen, I sported a plastic Walther PPK, frequently confiscated by my teachers, and I practiced a plummy English accent until I had it down cold.

I saw every Bond film on opening day after that. For years, it was the one ritual my father and I shared. And it was Moore’s Bond that formed my sense of the character. An undiscerning 21 year old, I even liked the snow-surfing opening of A View to a Kill, which appalls me now. I dutifully caught up on the Connery Bonds, many via the ABC Sunday Night Movie, others in second runs in the theaters. I knew I was supposed to like those movies better but as a teenager I was shamefully drawn to “my” Bond. Sean Connery was my father’s Bond (Dad was born in 1927, the same year as Moore), and though he thought the Moore flicks were great fun, he was adamant that Connery was the only true Bond. When I took him to see Casino Royale in 2005, I asked him what he thought. He shrugged and said, “I prefer my Bond.” Perhaps this is the universal response to 007. We all prefer our Bond. We never forget our first.

There’s something inescapable about Moore’s Bond for me. He’s wrongly dismissed as a lightweight. He may have preferred to lean on his easy charm but he could also bring it with the big dogs. His 1973 Bond is already fully formed, and although he wobbles a bit throughout the rushed follow-up The Man With The Golden Gun, his turn in 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me is widely regarded as his finest, the perfect mix of charm and danger. It’s the movie that gives us the underwater car, pyramids and nuclear submarines, but you had me at the Union Jack parachute.

After that came the widely-derided Moonraker, the producers’ attempt to cash in on the Star Wars craze, and it tips dangerously into the absurd but two moments stand out. Bond is nearly killed by a centrifuge run amok, only to be rescued by, yes, Doctor Holly Goodhead. When the bad guys come for Bond, he usually fends them off with a straightening of the tie, a brushing off of the sleeve, a pun that makes us groan. But this one hurts, and Moore stumbles out, refusing her assistance and eschewing the usual quip. It’s a humanizing moment amid the comic book excess, one that Fleming might have recognized.

At another moment in the film, Bond is out strolling the grounds with the villain of the piece, Hugo Drax. They are pheasant hunting and Drax, a wonderfully silky Michael Lonsdale, encourages Bond to have go. Bond fires at a bird and misses and Drax cannot contain his gloating, until an hidden assassin drops from the trees, felled by Bond’s shot. Because, as we know, Bond never misses. “As you said,” Moore says, handing the weapon back to Drax, “such good sport.” Oftentimes, the quips are dreadfully corny and call for the overly self-aware delivery Moore made his trademark. But this one’s a good line and his delivery is low key, spot-on; dare I say, Connery-esque?

It’s a popular point in the Connery v. Moore argument to observe that Connery was truer to what Bond’s creator had in mind. But Fleming gave Bond an after-the-fact biography that aligned more with Connery’s following the success of the first two films. For all that, whereas one can more easily see a young Roger Moore getting chucked out of Eton at twelve (as Fleming describes in You Only Live Twice, for “alleged trouble with one of the boys’ maids”), it’s harder to imagine the rough-hewn Connery getting in to begin with. But even before Moore holstered his PPK, the films had left the world of the novels far behind. Though Fleming delighted in outsized villains and women with questionable names, the fact that Bond was an assassin, a cold-blooded killer, remained front and center.

By the 1970s, Bond was more of a gentleman killer, and Moore’s films came to define what a generation associated with 007. Every second or third summer, we expected charm, we expected breathtaking locations and big budget action set pieces, we expected not always funny quips (to groan was the point), we expected timely gadgets.

If that legacy has been supplanted by Daniel Craig’s dour, existential Bond, it cannot be fully erased. The Moore Bonds are joyful, globetrotting spectacles before Bond got a terminal case of the downs. Unlike Connery, whose relationship to his alter ego was fraught, Moore clearly loved every moment of being 007, and his delight is palpable in the films. (Perhaps it’s not a coincidence that a similar delight can be detected in Brosnan’s underrated Bond, whereas Craig infamously said he’d rather “slash my wrists” than return to the role.) One cannot imagine Sir Roger saying, as Connery told Playboy in 1965 at the very height of international Bondmania, “Bond’s been good to me, so I shouldn’t knock him, but I’m fed up to here with the whole Bond bit.” Moore was thrilled with his lot (he titled his 2014 memoir One Lucky Bastard) and in nearly every between-takes photo from the 70s and 80s, his huge grin and even huger cigar are inescapable.

The Bond series has always been canny about reboots, returning to basics just as things threatened to go too wildly over the top. One of Moore’s best turns as Bond follows Moonraker, the stripped down 1981 For Your Eyes Only, in which Bond is bruised, beaten and bloodied. It’s a strong gritty turn but he’s already looking a bit long in the tooth here. (He was the oldest actor to play Bond, 46 when he assumed the role.) In this youth obsessed age, we’re unlikely to see any other actor maintain such a long reign at MI6; Brosnan lasted only four films, and Craig is probably close to finishing out with five though the London bookies keep that an open question.

It’s true some moments are best forgotten: the ridiculous clown suit in Octopussy. The aforementioned pre-titles sequence of A View to a Kill. Well, pretty much all of A View to a Kill. The embarrassing sexism and the dated pop cultural references. Loving Bond can feel like something you need to apologize for, and the brief against the Moore years is a solid one, hard to argue with. The ham-fisted Blaxploitation cash-in of Live and Let Die is redeemed largely by Yaphet Kotto’s brilliant and mercurial Mr. Big.

But Roger Moore remains, for me, a wide-lapelled icon of the 1970s and of my youth, as distinctive and memorable as the AMC Pacer he flips so casually in The Man with the Golden Gun. And every few years, I sit in a movie theater on opening night, my nine-year-old heart racing as I wait for a familiar gun barrel to scroll across the screen. If it feels like a betrayal to confess my ultimate Connery preference (something I reluctantly conceded in my 30s), I still note that the one-sheet for Live and Let Die is the poster I hang in my home.