As a junior faculty member with a Humanities appointment, and especially as one who studies migration, it feels like I encounter the word “crisis” on a weekly, if not daily, basis. Journalists love the word “crisis.” Higher education publications bombard us with crisis-oriented rhetoric to describe changes in Humanities enrollment and in employment opportunities across the country. My research consistently reinforces for me that world leaders and politicians have convinced the public that we are currently facing a global migrant crisis. That phrase has become a household utterance even though most people can’t tell you why or what it means.

I contend that stories are what the Humanities have to offer the public and their elected officials as we contemplate our role in the lives and futures of displaced people.

So what do stories have to do with refugees?

Although the United States and countless other global powers are reducing their national quotas for the resettlement of refugees and asylum-seekers, the cultural appetite for the stories of refugees is increasing. Novels and short stories by members of refugee communities who have overcome tragedy and lived to pen their tales continue to appear on bookstands, best-seller lists, and in independent book stores. In the face of sensationalized media discourse on the global migrant crisis, it is the role of literature and culture, whether autobiographical or fictionalized, to remind us that our conversations about a “crisis” are about the lived realities of people, who love and live just like we do, but who are unlucky enough to find themselves in a conflict zone.

At the beginning of October 2019, The New Humanitarian ran a public scholarship op-ed article by Benjamin Thomas White, “Talk of ‘unprecedented’ numbers of refugees is wrong – and dangerous.” This piece seems to have been written in response, in part, to recent sensationalist news claiming that the number of displaced people is at a historical high. As White explains, these claims are unfounded. In addition to asserting that these headlines are misleading at best and false information at worst, however, White also points out that the oversimplification of discourse surrounding displaced peoples likely leads to the international panic that labels it a “crisis.” He writes:

Talking about the unprecedented scale of current displacement reduces the complexity of many different displacements, with many different causes, to a single and impossibly huge “crisis.” This is likely to make members of the public, or politicians, less able to understand and contextualize specific displacements, and less able to imagine smaller-scale but more practicable solutions. And it reduces millions of different individual lives to this one big number, 70.8 million. This is a problem, because you can’t feel sympathy for a statistic. By abstracting individual humans out of the picture, stressing the “record number” of displaced people risks decreasing, not increasing, public sympathy and support.

In other words, the language of “crisis” causes the public to feel resignation that people facing displacement could be resettled successfully and transforms individuals with lives that started well before they became displaced into a kind of invasive swarm; the language of “crisis” robs situations of their specificity and people of their humanity.

Benjamin Thomas White’s arguments are international in scope, but also apply directly to the phenomenon we are presently witnessing in the United States. Donald Kerwin, Executive Director of the Center for Migration Studies in New York, recently published an essay that focuses on the United States and Trump administrations, specifically. He addresses the historical precedent, in which the United States was an international leader in the resettlement of displaced populations in the aftermath of World War II and the Vietnam War.

He urges us to note, however, that the tides have changed:

Yet although the United States remains the largest donor to the United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees, the Trump administration has sought to steer the country in a different direction. The United States now seems poised to become the global leader in refugee responsibility shunning and of exclusionary nationalist states, whose leaders the president regularly praises, fetes and seems to emulate.

Among the policy changes Kerwin outlines, we find the September 26th President’s annual Report to Congress on Proposed Refugee Admissions for the Fiscal Year 2020, which provides for the admission of 18,000 refugees, the lowest number in the history of the US Refugee Admissions Program. (For an overview of how the Refugee Admissions Program operates, see the CMS’s 2018 Executive Summary.) Notably, this number is lower than the quotas the country set for 2002 and 2003, in the aftermath of 9/11.

Despite declining political support for refugee resettlement programs, refugee “must-read” lists proliferate the internet. The titles that appear on these lists vary widely and include both retellings of stories that are decades old (but have taken on new meaning due to global affairs) and critical examinations of contemporary political situations. It could be argued that publishing houses want to influence public opinion on the topic and, thus, are publishing more books that put the humanity back into refugee statistics. However, the mainstream publishing industry is notorious for evaluating manuscripts strictly for audience and sales potential, which I take to be an indication that these books are already selling and resonating with the general public. (See, for example, the Penguin Random House list, “Excellent Books to Understand the Refugee Experience,” which claims to promote “compassion and empathy” for the world’s refugee population.)

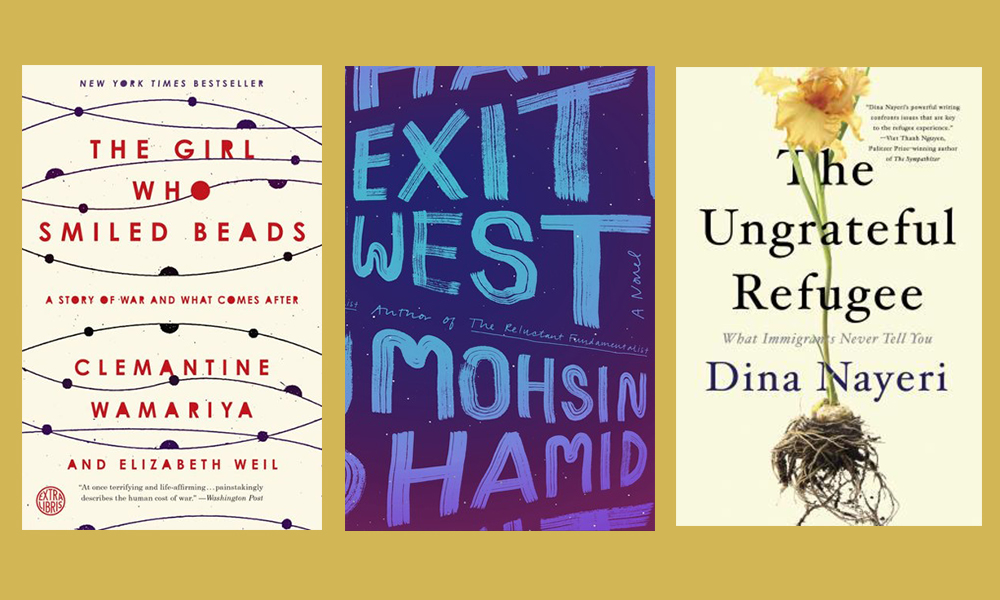

Perhaps one of the most salient contemporary examples of refugee literature is Clemantine Wamariya’s The Girl Who Smiled Beads: A Story of War and What Comes After, released in 2018. Wamariya’s memoir captures her flight from the Rwandan genocide in 1994 and escape to refugee camps before finally being resettled in the United States. American awareness of the Rwandan genocide did not crystallize until the release of Hotel Rwanda in 2004, which is about the time the American public also learned that our government was aware of the genocide and chose not to intervene (see The Guardian’s article on the declassification of government documents). In retrospect, most Americans recognize the Rwandan genocide as a tragedy. Wamariya’s memoir, a contemporary retelling of a story associated with this particular historical moment, helps readers make connections between past and present.

A second example, Mohsin Hamid’s 2017 novel, Exit West, serves a slightly different purpose. The novel feels like a magical realist narration of the fate of two lovers, doomed by civil war and international inaction to a life of struggle and loss. The novel begins in an unnamed city that is likely meant to stand in for Damascus or another metropolis affected by conflict in Syria. It combines the topic of asylum-seeking with a powerful love story and calls on readers to remember that displaced people have families, feel pain, and struggle with difficult decisions just like everyone else. Perhaps these are the ingredients that propelled the book to the top of The New York Times’ list of 10 Best Books of 2017.

Recently, I had the pleasure of meeting Dina Nayeri at a reading hosted by Brazos Bookstore in Houston, Texas. Her book, The Ungrateful Refugee (published earlier this year), is another example of the demand for refugee literature. Nayeri’s writing assembles the experiences of refugees she has met and interviewed — à la ethnography — with her own story and memories of living in a refugee camp. The end result is a curated, collective memory piece that throws into question what it means to be a refugee and how it alters the contours of someone’s life. During the Q&A session that followed, I was struck by Nayeri’s comments that seemed to imply non-refugees view refugees as fragile; she explained that what refugees often need most is not to feel sheltered or protected but rather to feel useful. She reminded the audience of the power of asking someone for a favor, so that they can be of service to someone else. Her book conveys many of these simple life-lessons that when viewed collectively give us a fuller perspective on the struggles confronted by the 70.8 million people wrapped up in a statistic.

Each of these titles represents a nuanced version of the growing genre of refugee literature, which seems to be captivating audiences despite changes in policy that could otherwise be read as indicative of declining support for refugee resettlement. These voices are examples of how the Humanities have the power to put the human back into the statistics that flash across our television news programs — the individuals who make up the “crisis” are each a Clemantine Wamariya, a pair of lovers like those imagined by Mohsin Hamid, or a person currently struggling with the waiting-game that is refugee resettlement, like those portrayed by Dina Nayeri.

A handful of smaller organizations, such as non-profit literary magazines and publishers, have also taken up the mantle of giving readers contact with a population that might otherwise remain nameless and faceless. Perhaps the most salient example is World Literature Today, published at the University of Oklahoma. The editors at WLT choose to address the topic consistently. For example, the autumn issue 2019 recently featured an interview with Monique Truong, a Vietnamese refugee who arrived to the United States in 1975, and a second, deeply-moving interview with Craig Santos Perez. In the latter of these two Perez describes the relationship between his poem, “Teething Borders,” and evolving policies along the US-Mexico border. Perez calls for a more “tender country” by highlighting “the violent reasons why people are driven from their homes” and underscoring “the fact that half of the refugee population are children.”

McSweeney’s, an independent book publisher based in San Francisco, published Refugee Hotel, a mix of photographs and narratives, that capture the live experiences of refugees on American soil, in 2012. The powerful book seems to anticipate many of the conversations we are having surrounding asylum-seeking in American today. The collection includes testimonial-style interviews with people who describe how it is they came to live here and what their first day in the US was like. McSweeney’s also releases what they term a Quarterly Concern. Issue 52 is In Their Faces A Landmark: Stories of Movement and Displacement, which contains seventeen shorts by seventeen authors with unique stories; the overall effect of the collection is that it highlights the vast array of experiences that somehow also contain universal themes.

There is no lack of American interest in the stories of individuals or families who risk everything to flee persecution and start their lives over. The trend is visible across registers of writing and publishing. Our changing government policies are not reflective of the public’s empathy for people whose goal is survival. Why are the policies changing? Perhaps the answer boils down to leadership that is out of touch, but my suspicion is that we have also grown desensitized to the fact that when we are talking about refugees, we are talking about people and not numbers. The Humanities — an entire discipline dedicated to studying humans and to put them back into scholarly inquiry — might just be the solution to this problem set.

I don’t know if the global migrant crisis will ever offer a compelling argument that we should reevaluate our assessment of the value of the Humanities in our education system, but I do believe that the Humanities hold a special place in the project of reducing the language of crisis and getting back to nuance in our problem-solving.