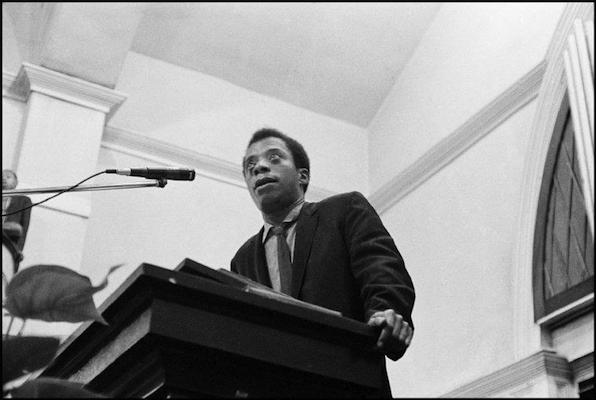

On October 16, 1963, James Baldwin delivered a speech to a group of teachers entitled “The Negro Child — His Self-Image,” which was later that year published in the Saturday Review as “A Talk to Teachers.” This was a year of great turbulence and strife as the fight for Civil Rights was being waged and a toll was being exacted on Black lives, young and old. On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his now iconic “I Have a Dream” speech, in front of more than a quarter of a million people gathered at the March on Washington. A few months before that, on June 12, 1963, Medgar Evers, pioneering civil rights leader and field secretary for the Mississippi chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), was murdered outside his home. And just a month before Baldwin’s talk, on September 15, 1963, four young Black girls were brutally murdered when the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, a frequent gathering site for civil rights meetings, was bombed. Baldwin, outraged by the cruel theft of these young girls’ lives, was also deeply concerned by what he viewed as a lack of broad “public uproar,” outside the Black community. And though he was not a teacher himself, he seemed to harbor a desperate hope that sounding a warning to those who shape young minds in classrooms across the country might be a way forward.

Baldwin opens his remarks, leaving no ambiguity about the crisis. “Let’s begin by saying that we are living through a very dangerous time … We are in a revolutionary situation, no matter how unpopular that word has become in this country. The society in which we live is desperately menaced, not by Krushchev, but from within.” He goes on to explain that, “What is upsetting the country is a sense of its own identity.”

Fifty-four years later, as we continue to reel from the impact of the election of Donald J. Trump as the 45th president and contemplate the “menacing” forces at work that made his election and his regressive campaign and policies possible, Baldwin’s words ring just as true. We are a deeply divided nation. Each week, the President and his administration find new ways to roll back civil rights protections for marginalized populations. And correspondingly, there continues to be an alarming uptick in hate crimes and instances of xenophobic harassment. Disproving that all progress made on civil rights is irreversible, our current socio-political climate reflects some of the essence of Baldwin’s observations of that turbulent era. “The political level in this country now, on the part of people who should know better, is abysmal.”

All manner of theories has been put forth by political pundits as to how the country descended into its current socio-political state, — some of the same pundits who inaccurately predicted the outcome of the election. Ultimately, to truly move forward as a nation, we must embrace shared ideals shaped by the crucible of a true and shared understanding of our nation’s history, an understanding that acknowledges not just our triumphant moments, but moments when we fell gravely short of upholding these ideals. And to arrive at this shared understanding of our nation’s true history, we must revisit our classrooms, where many of us first learned about American history, albeit a version which often was incomplete and incongruent. We must follow the trail of the red ink of revisionist history that fills many of our textbooks, classrooms, and consequently, our own understanding of our national identity.

Baldwin’s talk is so prescient of our current situation because of his unerringly perceptive understanding of how some of our country’s most entrenched ills are rooted in our inability to grapple with our true history, as well as our lack of meaningful progress on this front over the last several decades. Baldwin asks the gathering of teachers to imagine the impact of a paradigm shift in teaching American history. “If, for example, one managed to change the curriculum in all the schools so that Negroes learned more about themselves and their real contributions to this culture, you would be liberating not only Negroes, you’d be liberating white people who know nothing about their own history. And the reason is that if you are compelled to lie about one aspect of anybody’s history, you must lie about it all. If you have to lie about my role here, if you have to pretend that I hoed all that cotton just because I love you, then you have done something to yourself.”

However, despite Baldwin’s plea, many obstacles continue to prevent us from teaching and learning history in a meaningful way. “History Class and the Fictions About Race in America,” published in the Atlantic in 2015, details these myriad issues. The article explains that when it comes to history teachers, according to a 2012 report by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences focused on high school educators, 34 percent of history teachers had not majored in history or received certification to teach it, and points to lax and varied licensing policies and requirements from state to state. It goes on to cite another report by the National History Education Clearinghouse which showed that only a small percentage of states require college course hours in history for certification, and no states require a major or minor in history for teachers. The article points to a 2013 Gallup Poll that reveals that few Americans “valued” their history classes, and quotes a Carnegie Corporation report on the consequences of this: “students who receive effective education in social studies are more likely to vote, four times more likely to volunteer and work on community issues, and are generally more confident in their ability to communicate ideas with their elected representatives.”

James W. Loewen, the author of the 1995 book, Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong, observes that many history teachers use textbooks as a “crutch.” There have been several examples of inadequate and problematic content in textbooks and educational materials, but one of the most egregious examples recently involved textbook giant McGraw-Hill. In October 2015, a controversy unfolded when it was revealed that a McGraw-Hill world geography textbook explained immigration patterns for the Southeast corridor of the United States with a caption that stated: “The Atlantic Slave Trade between the 1500s and 1800s brought millions of workers from Africa to the southern United States to work on agricultural plantations.” McGraw-Hill was blasted, and rightly so, for so blatantly mischaracterizing slaves as willing “workers,” and forced capture and migration as immigration. But while this was a particularly glaring error, it’s not certain that errors like this one are all that rare. The Atlantic article noted a National Clearinghouse on History Education brief reviewing four elementary and middle-school textbooks which found that they “left out or misordered the cause and consequence of historical events and frequently failed to highlight main ideas.” If one is not taught the causes and consequences of a historical event or social issue, what historical lesson has been gleaned, what truth has been conveyed? These factual errors are not only betrayals of our youth by our education system, but impediments to achieving a true and shared understanding of our history and national identity. And can we build our future if we can’t reconcile our past?

How do substantive factual and contextual “errors” like the one in the McGraw-Hill textbook happen and how do they find their way into textbooks throughout a state and throughout the country? First, there is the often-noted fact that the publishing industry, including its editorial staff, is woefully undiverse (79% to 89% white, varies by source of survey data). However, while this might elucidate how history books reflect an incomplete or biased version of history, this doesn’t fully explain egregious factual errors or mischaracterizations. Sometimes, these “errors” reflect successful attempts to infuse curriculums with regressive ideologies or agendas. For example, in 2010, the Texas school board passed a ban on books with “anti-Christian, pro-Islamic slant(s).” Similarly, in January 2013, Arizona instituted a ban on the use of the Mexican-American studies curriculum used in Tucson high schools. And most recently, in March of this year, a state representative of Arkansas introduced legislation to prohibit the inclusion of books and materials by A People’s History of the United States author Howard Zinn within Arkansas public school curriculum. Meanwhile, textbook publishers like McGraw-Hill are eager to win contracts for large state public schools systems, of which Texas is amongst the largest and most influential, and are at the very least indirectly influenced to draft content for their textbooks in a way that is perceived as inoffensive and uncontroversial to these states’ textbook adoption bodies. Ultimately, all these issues and influences jockey with actual facts and the true context of history in classrooms across the nation, but especially in classrooms in “red” states.

However, it’s not just conservative white Americans who are looking to make American classrooms the sites for their revisionist history. In January of 2016, California’s State Board of Education requested input for its History-Social Science Framework curriculum and was besieged by controversial and contradictory public input for the South Asia component of the Framework. Pro-Hindu and India-centric organizations, including the Hindu American Foundation and the Uberoi Foundation were pushing for revisions to the Framework including replacing certain references to “South Asia” with “India,” and revising descriptions and characterizations of India’s caste system to be more tied to social and economic class rather than Hindu doctrine and practices. These groups went so far as to say that the Framework’s depiction of caste was anti-Hindu and could be stigmatic to California’s Hindu students. Meanwhile, a loose coalition of organizations representing broader South Asian interests, including Sikhs, Muslims, and Dalits, as well as an inter-institution South Asia Faculty Group, sought to push back against what they viewed as pro-Hindu and India-centric revisions, characterizing them as both revisionist and reductive history, even creating a Twitter campaign: #DontEraseOurHistory. The California State Board of Education body ultimately rejected most of the Pro-Hindu, and India-centric proposed revisions, however the controversy illustrates once again that the American classroom has become a battlefield for those who seek to revise history. But it also makes evident this battle is not just between white and minority Americans over their respective roles in American history, but also within marginalized populations, grappling with their own divided and contested histories.

Beyond expressing his deep concerns about the long-term sociopolitical impact of being a nation unwilling to grapple with its true and whole history in the classroom, in his speech, James Baldwin also expresses his thoughts on the core purpose of education in society. “The purpose of education finally, is to create in a person the ability to look at the world for himself, to make his own decisions, to say to himself this is black or this is white…” Baldwin acknowledges that, “what societies, really, ideally want is a citizenry which will simply obey the rules of society,” yet he warns that, “if a society succeeds in this, that society is about to perish.” And he notes that this is the paradox of education within a fraught social framework. Baldwin concludes, “The obligation of anyone who thinks of himself as responsible is to examine society and try to change it and to fight it — at no matter what risk. This is the only hope society has. This is the only way societies change.”

A true and meaningful education, Baldwin suggests, empowers students to not only examine fraught aspects of their society but also their role within the system. Students of color are subjected to inequitable accounts of history in the classroom, minimizing the contributions of their respective communities, but also face inequities in their lives outside the classroom. Baldwin expresses his hopes for the student of color:

I would try to make him know that just as American history is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it, so is the world larger, more daring, more beautiful and more terrible, but principally larger — and that it belongs to him. I would teach him that he doesn’t have to be bound by the expediencies of any given administration, any given policy, any given morality; that he has the right and the necessity to examine everything.

Meanwhile, when it comes to white students, he fears the harm also caused to them by internalizing inequitable historical accounts in and out of the classroom, thwarting their understanding of themselves. “And a price is demanded to liberate all those white children — some of them near forty — who have never grown up, and who never will grow up, because they have no sense of their identity.”

With the election of President Trump, we are left to contemplate not just how we got here, but whether this marks the beginning of a stark new reality or the inevitable continuation of our nation’s history. But if we seek to alter our course, we must know from whence we came. Baldwin concluded his speech delivered to teachers during the midst of the Civil Rights movement by saying the following, and 54 years later, his words echo, not as a history lesson, but as a vision for our future. “America is not the world and if America is going to become a nation, she must find a way — and this child must help her to find a way to use the tremendous potential and tremendous energy which this child represents. If this country does not find a way to use that energy, it will be destroyed by that energy.”