Last month, Stanford University announced its plan to remove from campus most references to Junipero Serra, the Spanish Franciscan priest who founded nine Catholic missions in California between 1769 and 1784.

The decision was not unexpected, given recent national opposition to statues memorializing figures from America’s violent past, even in California. But I have mixed feelings about the removal of Serra’s name. The underlying politics seem more reactionary than progressive. Junipero Serra was no saint, although he was in fact canonized, amidst controversy, by Pope Francis in 2015, as the first Hispanic saint in the United States.

By removing the name of a Catholic Spanish Californian and replacing it with a Protestant English-speaking figure — Jane Stanford — the university threatens to further the dominant national narrative that English is the language of American history. As much as I support the policy of honoring women, the erasure of Serra’s name means less public attention to the Spanish-speaking foundations of the United States at a moment when debates about Hispanic immigration and citizenship are at the forefront.

Many Americans outside of California have little understanding of the role Spanish explorers and missionaries had in settling the western part of the continent. While Serra biographer Gregory Orfalea asserts that Serra is “virtually a household name in California, where all fourth graders are required to study him and the missions,” American history textbooks generally minimize the nation’s Spanish-speaking colonial past. Nor do more populist histories correct this slight: Serra’s name does not even appear in Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States (1980), Paul Johnson’s A History of the American People (1997), or even Jill Lepore’s new, nearly 1000-page These Truths: The History of the United States (2018).

It is certainly true, as the Advisory Committee on Renaming Junipero Serra Features states, that “the mission system subjected Native Americans to great violence and, together with other colonial activities, had devastating effects on California’s Native American tribes and communities” and that Serra “was a zealous proponent of the mission system and its leader in California.”

And as Benjamin Madley describes in An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873 (Yale UP 2016), native Californians were seen by missionaries as “pagans and gente sin razón, or people without reason,” to be transformed “into Catholic workers by replacing indigenous religious, cultures, and traditions with Hispanic ones.” Spanish soldiers preyed on Native women and Serra endeavored — but regularly failed — to protect them.

But on the Atlantic coast, what founding American figure isn’t equally implicated in the destruction of native culture even if most lived and wrote long after native populations on the Atlantic coast were decimated, destroyed, and driven west? What if in the 1750s Benjamin Franklin had somehow found himself on the other side of the continent? Recently reading Orfelea’s Journey to the Sun: Junipero Serra’s Dream and the Founding of California (2014), I saw Serra as a kind of Spanish Franklin, playing the role of influencer, community builder, and power broker during the exact same years that Franklin was influencing, building, and brokering on the East.

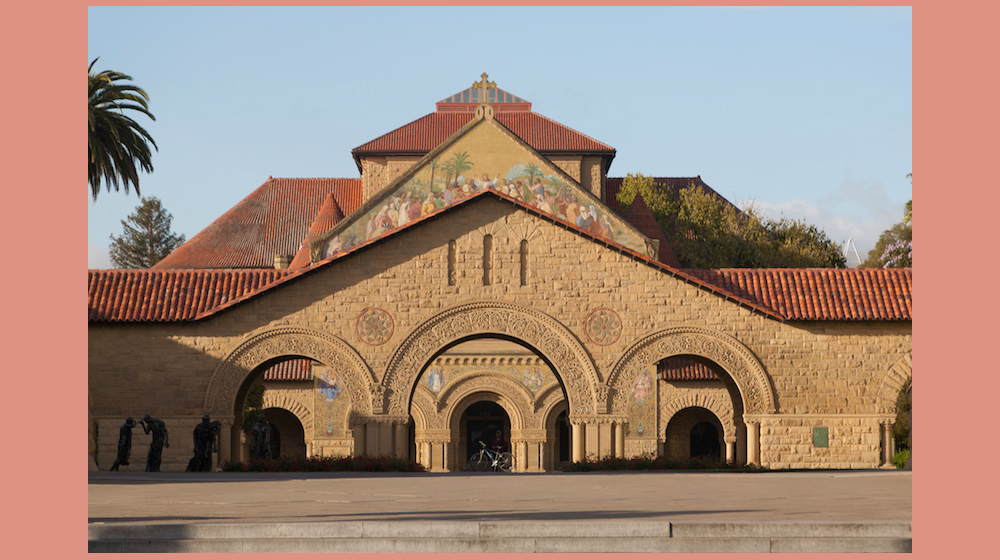

The witty and energetic Junipero Serra (1713-1784) was born in Europe, joined the Franciscan order in his twenties and worked as a university professor before volunteering to become a missionary in Mexico in his thirties. Serra was so successful in establishing mission churches in the 1750s that he was sent to Baja on the Pacific coast and subsequently north to California to establish missions and baptize native communities from San Diego to Monterey. It was on the basis of Serra’s importance as a founding father of California that Stanford named so many campus features after him.

The witty and energetic Ben Franklin (1706-1790) arrived in Philadelphia, in 1723, after most of the native Delaware and Shawnee population had been killed or urged West by gunpoint or bribery. For three decades Franklin had a relatively conflict-free stage to establish himself as a printer, scientist, and community builder. But an uprising in 1755 and 1756, in the context of the French and Indian wars, required military action. Franklin’s duty, as he describes in his Autobiography, was to “take charge of our North-western frontier, which was infested by the enemy, and provide for the defense of the inhabitants by raising troops and building a line of forts.” While the 560 armed men under Franklin’s command saw no direct action, he describes deadly skirmishes with casualties on both sides all around him.

In short, one of these two men went into battle against Native Americans and it was not Junipero Serra.

The Stanford Advisory Committee acknowledges that larger structural forces were more to blame for the devastation of native communities and cultures than Junipero Serra himself: “Historical references indicate that he combined piety, self-sacrifice, a love for Native Americans, and a religious passion for their salvation with strict and punitive paternalism, sometimes moderated by significant acts of leniency.”

Meanwhile Walter Isaacson, in his highly praised biography, all but ignores Franklin’s role as an armed combatant. “Franklin enjoyed his stint as a frontier commander,” Isaacson writes, focusing on Franklin’s efforts to get militiamen to go to worship services and his interest in the marriage customs of nearby Moravians. “After seven weeks on the frontier, Franklin returned to Philadelphia.”

So while the California Mission system was devastating to native culture and that the Spanish military presence was genocidal, perhaps Serra’s life and work ought to be evaluated in comparison to the Colonial-era Native American experience on the Atlantic coast. The devastation of native communities by English speaking colonists was arguably more brutal.

Accordingly, I was particularly disappointed in Jill Lepore’s omission of Serra, given her scholarship on the Indian Wars of New England and on Jane Franklin, Benjamin’s sister.

Erasing Serra’s name because of the broader narrative of Spanish cruelty toward indigenous people in the New World lessens English responsibility for Native American genocide. The Stanford committee might note how anti-Spanish sentiment was deployed a century ago by Stephen Austin, the “founder” of Anglo-American Texas (and whose name still graces universities and office buildings today), to describe “a war of barbarism and of despotic principles, waged by the mongrel Spanish-Indian and Negro race, against civilization and the Anglo-American race.”

As the historian Tony Horowitz described twelve years ago in an article for The New York Times, “Immigration — and the Curse of the Black Legend,” erasing the Spanish history of America is a matter of “national amnesia” that is “glaring and supremely paradoxical at a moment when politicians warn of the threat posed to our culture and identity by an invasion of immigrants from across the Mexican border.”

The genocide of Native Americans is a collective guilt that is shared intersectionally, from the Jamestown settlers to Calamity Jane to the African American Buffalo Soldiers, now honored annually at West Point. Perhaps Stanford might reconsider its decision and ask: whose politics is being served by the erasure of Junipero Serra’s name and the privileging of English language history?