In an age of eroding privacy, many of us may wonder why we are so willing to share our most private details with the rest of the world. The common wisdom is that Silicon Valley taught us how to promote ourselves and taught us to eschew privacy. After all, we often blame social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for making us into a nation of self-revealing narcissists. But while social media facilitates this behavior, it is not solely responsible for it. Silicon Valley is the culmination, but not the origin of our obsession with self-presentation.

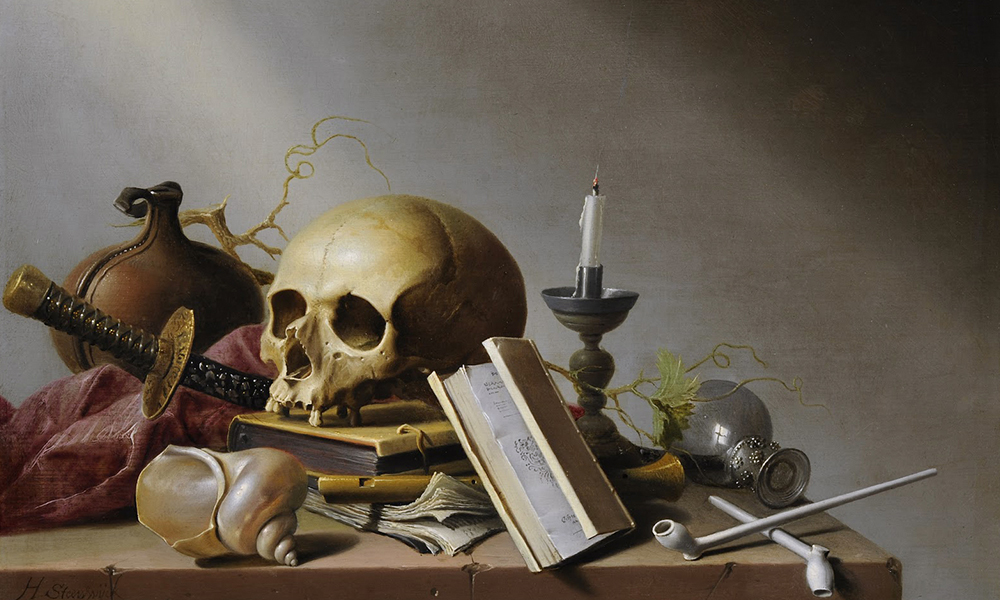

To understand how the national preoccupation with self-presentation took root, one needs to go back two centuries. For men and woman living in the 18th and 19th centuries, our cavalier exhibitionism would have felt foreign. Most believed that it was pointless and wrong to be proud of one’s achievements or possessions, since the grave would, sooner rather than later, steal those things back from you. Connecticut preacher Solomon Williams explained this to his congregation in 1752: “Our Days on Earth are as a Shadow … it is a vain Life. A Shadow is a thin airy Image, which has no Substance in it; … It flies from you, and runs away as fast as you pursue it.” Because life was itself vain, colonial preachers counseled humility. As Williams put it, “we should live in an humble sense of our meanness …” In today’s world, however, such advice seems out of tempo with the times.

The shift in disposition from William’s day to our own is the result of two hundred years of technological change and capitalist growth. The development of the postal service and low postage rates in the 19th century encouraged letter writing and taught Americans to talk about themselves in ways they had previously resisted. As a letter writing manual of the time gently advised: “The friendly letter is the very place for egotism.” The invention of photography in 1839 also served to awaken people’s sense of self as well as the nascent desire to express that self. For colonial Americans, a painted portrait was something only the affluent could afford. But by the late 19th century, a small photograph cost only 25 cents, and as a result, Americans of all races and classes were flocking to photography studios to have their picture taken. Finally, mirrors, which had been scarce in colonial times, became ubiquitous in middle-class households by the late 19th century, further amplifying Americans’ growing sense of self and how that self might appear to others.

These technologies did not immediately or completely banish older worries about vanity and the transience of life. Indeed, many hoped these new tools might be morally improving. For instance, early commentators on photography believed the camera would eliminate vanity, for unlike portrait painters, who might flatter their subjects, the camera was more honest, and showed all of one’s flaws. Some also patronized photography studios precisely because they realized life was short. Grieving families frequently had photographs taken of their recently deceased kin, so much so that historians estimate that in the 1840s and 1850s there were more photos of dead children than living ones. And many photographers capitalized on this belief, urging their customers to “Secure the shadow, while the substance yet remains …”

Yet while Victorians carried these older notions of vanity in their heads, strictures on the behavior were loosening. With photography, Americans became accustomed to studying their own images. And with the spread of the postal service they filled the mails with letters and photos telling friends and family of their recent doings. These were the ancestors of Facebook and Instagram posts. With the growth of consumer capitalism in the early 20th century, the idea of sinful vanity declined further. To spur consumption, advertisers appealed directly to people’s egotism and pride. In 1914, for example, one clothier ran an ad asking, “Has your real vanity been tickled lately?” Also epitomizing this shift was the emergence of the word “vanity mirror,” which seemed to legitimize preening and perfecting one’s self-presentation.

As a result, Americans over the course of the 20th century gradually became accustomed to celebrating themselves in word and image, and sharing that self with others. Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, then, did not create these trends; they have merely amplified them.

For the last eight years, we’ve been studying such emotional transitions, trying to understand how technologies — from the telegraph to Twitter — have reshaped Americans’ emotional lives over the past two centuries. We’ve read the diaries and letters of 19th- and 20th-century Americans and interviewed 21st-century men and women living through the technological revolutions of our own day. And many of them have told us how their heightened sense of self has led them to think about promoting and marketing their identities, and increased their willingness to divulge intimate details about themselves to others. Indeed, some of the younger people we talked with told us it was essential to their social life to do so.

Yet in spite of technology and consumer capitalism, we are still vaguely aware of vanity’s older meaning. We police people who we think are taking too many selfies. We mock the duck face. And we’re uneasy about those, like our president, who have excessive self-regard. However, the words that we use to frame this concern have changed. Where pride and vanity were all the currency in Solomon William’s day, today we increasingly describe chronic selfie posters as narcissistic (a term that was not invented until the late 19th century). To be sure this new word still has a negative ring to it. But it emerged from the field of psychology rather than from religion. It pathologizes pride rather than condemning it as a sin. Sometimes too we use the word over-sharer, or frame critiques in terms of privacy. We don’t condemn people for sharing and celebrating their accomplishments; instead, we merely worry about them being careless about where they do this. As a result, the existential dimensions of vanity, and its ability to remind us that we’re mortal and that the human condition is limited, are generally lost to modern-day Americans.

In the age of surveillance capitalism, it is rapidly becoming a truism that the details from our private lives are fueling the fire in Silicon Valley. It is also true that the Valley gained access to this fuel as a result of technologies that amplify our desire to share every last detail of ourselves. But the tech companies did not manufacture that desire out of thin air. It was handed to them by a long history of technological change that fundamentally reshaped how we feel about self-expression and vanity.

Luke Fernandez and Susan J. Matt are authors of Bored, Lonely, Angry, Stupid: Changing Feelings about Technology, from the Telegraph to Twitter (Harvard University Press, 2019).

Photo: “Vanitas” by Harmen Steenwijck c. 1640.