You’re a man in the Middle Ages. You live in Rome, where employment options are few: farming; smithing; carving gargoyles for the cathedral; warring; becoming a monk so you don’t have to war. As a monk you can write prayers over and over again on sheets of paper made from skinned animals, or you can sit in the crypt and watch dead monks slowly putrefy.

Putridariums are no big deal. An underground room — wine-cellar-cool — is ringed by benches with holes cut in them, sometimes with armrests separating the holes. Like toilets, yes, or nice wingback chairs that could double as toilets. When a monk dies, you prop him up on the bench, carefully positioned so the fluids slowly leaching out of him will be funneled away by the ditch below. Regular burials take up space; after a man goes through this months-long defleshification, his bones get tossed in a communal sarcophagus. No muss, no fuss.

You’re a woman in the 21st century. You have a putridarium fetish. There’s apparently only one surviving set of crypt toilets in Rome, in the basement of Sant’Andrea delle Fratte, halfway between the Trevi Fountain and the Spanish Steps, so you make a pilgrimage there. Friday, 5:30 pm: a mass is in session. The sanctuary’s closed to tourists; they know you’re not Catholic. There are no signs for a crypt. It’s possible “putridariums” are a hoax.

Sitting in a putridarium is like watching a tree grow. Nothing happens, but the nothingness is massive. If you turn away (for a week) and turn back, a cheek will have sunk a centimeter more; a wound in the side will carry a few more larvae. The eyeball eventually pops. Your job is just to sit and watch, be bored, contemplate your boredom. At the next monk meeting, you’ll have to report back about the state of the corpses, and any revelations you’ve had about the meaning of mortality. So far you’ve come up with: you die, and then you keep dying.

You go back to Sant’Andrea delle Fratte the following day; there’s another mass. You’re not so easily swayed, and pretend to be devout in the back row, lip-syncing the “Ave Maria.” After, you assault the berobed organist.

“C’è una cripta?” you ask.

He smiles. “Sì, sì,” he says, “but is not possible.”

“Che?”

“Is not possible. Danger!” he smiles again.

“C’è un putridarium?”

He chuckles, his flesh underneath the cassock jiggling with life. “Yes, danger! Danger! Come with me.”

You trot behind him as he rounds the altar and points toward a table, below which a small grate in the floor covers a hole with a set of stone stairs descending into darkness.

“La cripta,” he says, laughing. “Not possible. Danger!”

If you were a mouse, you could squeeze through the grate. If you were a monkey, you could lift off the grate and scamper down the stairs. If you were a dead monk, you’re probably already down there, wondering where your watcher went.

You fall asleep at the job. Once you get used to the tender squelch of bile, keeping a putridarium is as mind-numbing as manning a tollbooth. Fewer cars, fewer quarters, less light, same smell. You wait for a sign of God’s tendresse. You wait for the wet kiss of the Holy Spirit. You wait for a woman to shout down the centuries at you: “Are you real? Is this something that really happened?”

You cannot see a putridarium in Rome — danger! — but there’s one in Naples, so you take the train. Underneath Santa Maria della Sanità, you break away from your tour group and rub your hands luxuriously, perversely, over the stone toilets. In the doorway, a man watches you. You imagine what it would be like to fall in love, whether that’s the thing that would thrust you into immortality, like Christ.

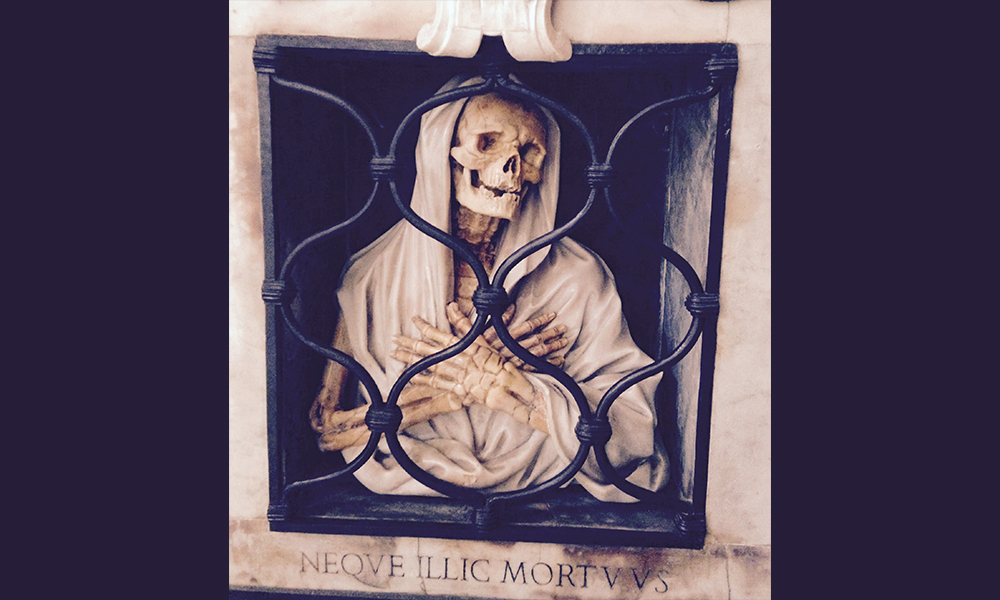

“Eternal life,” says the man, “has nothing to do with love.” When he steps forward, you can see the bones of his body, smooth as marble, impermeable now to time. “Living is fast, thank god, and loving is even faster.”

Katy Simpson Smith was born and raised in Jackson, Mississippi. She is the author of We Have Raised All of You: Motherhood in the South, 1750-1835, and the novels The Story of Land and Sea and Free Men. Her novel The Everlasting is forthcoming in March 2020. She lives in New Orleans, and currently serves as the Eudora Welty Chair for Southern Literature at Millsaps College.