I was running when the stranger leaned in, in the final 600 meters of a cross country race on my home course. He was yelling at the woman with whom I’d been in staggered lockstep for two and a half miles, and who had just now pulled two steps ahead. I’d been dazing, dreaming, falling away. “You’ll remember this moment for the rest of your life!” he screamed, though not at me.

There’s a parallel scene in Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein, a book we know better by other terms. Victor Frankenstein, after his creature’s series of crimes, has vowed to follow his creation north until they meet in “mortal conflict”; the creature, throughout the months that follow, remains ever just out of reach. I’ve always found the asymptotic quality of their chase chilling — this game designed, by definition, to continue for as long as Frankenstein and his creation remain alive.

My situation shared something with this experience. On this particular day, I had been racing “out of my head,” as one expression goes: racing well beyond a level of exertion I’d ever experienced and despite any rational evidence that what I was doing made sense. My head tilt, always present, now canted far to the right; my right foot kept coming in to knock the inside of my left calf; my bladder gave with every stride. Every runner, in every race, goes through something called a “stopping moment” — a moment when you imagine how nice it would be just to walk off the course. I was reaching mine. This was enough because it was too much.

¤

When have we hit the lowest point we can attain? And is pain something we can remember, much less share? I think about these questions nowadays when the distances imposed among us feel painful, and the stasis required by isolation feels, often, like too much. I think, too, about how literature meditates on these conundrums, and how my own transitions between running and writing have always felt seamless: from aspiring professional runner to English professor; from thinking as I run, to writing down those thoughts.

On paper, however, these pursuits seem so opposed — running, of the body; writing, of the mind. Pain, too, can feel contradictory, both isolating and communal, something that draws me inward, and also something that, in the context of running, helped dissipate my shyness and bring me friends. My closest prior relationships, I realized once I started running, had been with fictional protagonists, figures who could love me as a reflection of my mind. Twenty-four years later, when our cross-country course record (my rival’s) finally fell, I’d tell a newspaper reporter as much: “to race [her] was to race myself.”

Victor Frankenstein knows something about this kind of pursuit. In Frankenstein, a focus on movement pervades the novel, with the creation first pursuing the scientist throughout his apartments, the scientist on the run. And yet, even in these scenes it’s as if the thing Victor flees is also an anchor that will only let him range so far, in a daemonic corruption of the compass conceit so masterfully employed by John Donne. Frankenstein, “unable to endure the aspect of the being [he] had created,” rushes out of his laboratory but only to his bedchamber, and, after a bit of pacing, settles down for a nap. He is soon interrupted by the creature, and in response he moves, but again only partially, “taking refuge in the courtyard belonging to the house which [he] inhabited,” where he will pass the night tracing a radius around the scene and creature he wishes to forget. When, at dawn, the porter lets him out onto the streets, he exits but continues to circle the scene of the crime, such that he can soon stumble into his best friend from childhood, Clerval, and return with him to the scene of creation, his lab.

I make a joke of these behaviors when I teach Shelley, though I’m also sympathetic to Victor, here. As a long-time track competitor, I appreciate the irony of running for miles and miles in a circle, finishing quite literally at the place I began. Nowadays, hampered by old running injuries, I pace through my mornings on a backyard elliptical machine, watching replays from my favorite Olympic track events. Yet I’ve moved forward somehow, staying still. My machine running reminds me of my beloved laps in a now-closed pool; the track sessions that replaced my long runs when the fact of being a single mom meant that to run miles I had to orbit the infield where my children ranged; or the cross country running, cheered on by my family, that I did so much of as a young adult. Even there, I’d cover miles and miles to end up at my starting point. I always ran toward some consciousness of others; I always ran to come back home.

¤

The other book I can’t stop thinking about these days feels, at first blush, like the polar opposite of the pursuit scene from Frankenstein, or the memory of race day that keeps running through my head. “I’m trapped in a Beckett play,” I keep repeating to friends. My set is minimalist, my days indistinguishable, and the sun rises and sets (it keeps doing that at least) while little shifts. “Pancakes?” I’ll say one morning to my now home-schooled boys; “Cheerios?!” I’ll announce gamely, for variety and with great inflection, on the next. They seem relatively peaceful about the stasis; my dog, too, stares at me calmly from her chair. But while I’m trying to find the novelty in small changes, my zen-like focus is disturbed by the hope that our situation is temporary and I needn’t leave my remembered reality completely behind. I’m not living so much as waiting, and waiting jars painfully with my desire for movement, progress, pursuit.

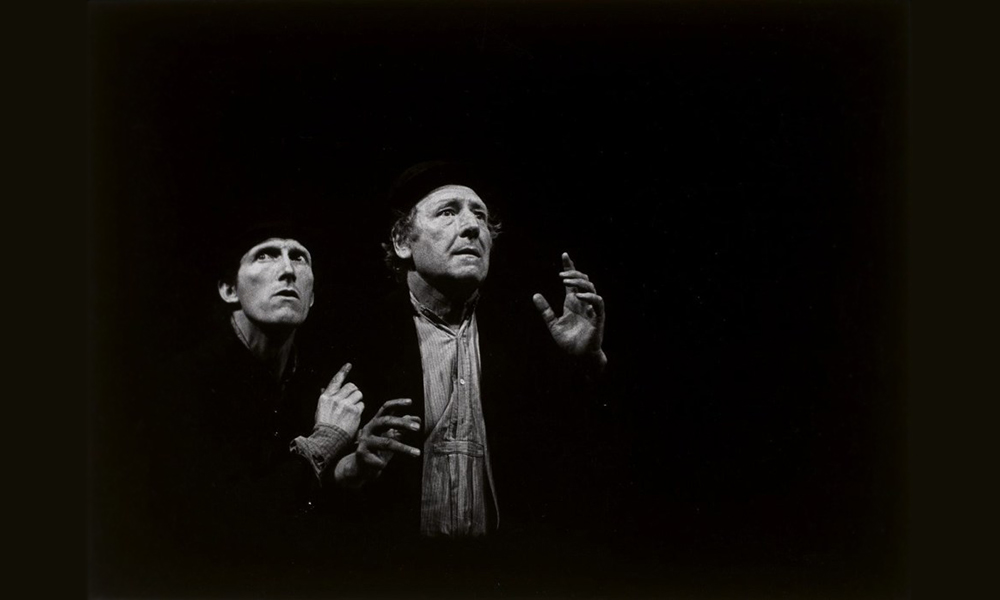

Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot has also been described as “a threnody of hope.” Featuring two protagonists who spend their time fixed nearly in place, their actions and purpose governed by an external figure who never appears, the play frames its titular “waiting” as a product of “hope deceived and deferred” but never fully quenched. When I re-read the play recently, the celebratory message in this description felt misplaced. Hope seems torturous to these two men — something that they’d be better off not having, something that blinds and binds them to their current status of neglect. Instead of models of human resilience, Vladimir and Estragon seem dupes who set themselves up to be overlooked. Hope doesn’t keep them moving forward; it prevents them from moving on.

I’m not alone in my prickly response. When Waiting for Godot was first performed in the 1950s, it created confusion, even ire. American viewers, less familiar than their European counterparts with theater of the absurd, believed they had been subject to a “hoax.” “The play concerns two tramps who inform each other and the audience at the outset that they smell,” wrote the American critic Marna Mannes. “It takes place in what appears to be the town dump, with a blasted tree rising out of a welter of rusting junk including plumbing parts. They talk gibberish to each other and to two ‘symbolic’ maniacs for several hours, their dialogue punctuated every few minutes by such remarks as ‘What are we waiting for?’ ‘Nothing is happening,’ and ‘Let’s hang ourselves.’ The last was a good suggestion, unhappily discarded.” Billed somewhat unfortunately in the US as “the laugh sensation of two continents,” the play inspired a “mass exodus” in Miami soon after the curtain rose. Attendance had apparently come to feel like duress. Why wait around, like Vladimir and Estragon, to get the joke?

Re-reading the story of these early failures makes me think about why we do sit still to read a book, watch a movie, watch a play — why a runner like me is equally happy to sit for hours and write. It also makes me consider why not all the early productions of Waiting for Godot failed. Indeed, a 1957 performance of the play at San Quentin fixed inmates to their seats. As one reviewer describes it, the watching prisoners, initially disgruntled, “listened and looked two minutes too long — and stayed. Left at the end. All shook.” Rick Cluchey, an inmate too dangerous to be released from his cell to see the production, and who merely heard the play broadcast, recalls that, “The thing that everyone in San Quentin understood about Beckett, while the rest of the world had trouble catching up, was what it meant to be in the face of it.” In the words of Cluchey, the play “caused [a] stirring.” In the face of captivity, suffering, stasis, something within the inmates — moved.

¤

To feel powerless, with time and agency stripped away: my children understand Beckett, too. “Time feels interminable when you are a child,” a friend reminded me, and the way children spend their time is often dictated from on high. To fill their few unscripted hours, children will make meaning out of space; I’ve seen mine find entertainment in boxes, blank paper, each other, air. And yet: “I’ve been here for so long,” said my five-year old the other day, after half an hour in the park. “Shall we go?” I asked, twitching, ready. They do not move.

Children also have trouble with empathy, a fact that makes me wonder how much childhood hurts. “Hurts! He wants to know if it hurts!” Estragon objects at the beginning of Beckett’s play. “No one ever suffers but you,” Vladimir responds. “I don’t count.” Victor Frankenstein is similarly self-absorbed, spending the novel asserting that his misery outweighs that experienced by others. All the protagonists considered here are childish in this regard. “How would you feel if…!,” I often mutter fiercely at my youngest, in response to some injury he has inflicted on his brother, trying to get him with words to enter an altered feeling state. His ability to answer my question is always hampered by some prior wrong, physical or emotional, that has been inflicted upon him. All he knows are those infinite realms of what he feels now.

And yet. I have two boys, just as there are two protagonists in Waiting for Godot, who circle each other like Frankenstein and his creature, their radius stretching just more tightly than the one that carried Victor to the North Pole. “He draws him after him,” states one Beckett stage direction. “We can still part, if you think it would be better,” suggests Vladimir; “it’s not worth while now,” Estragon responds. I’ve seen my oldest make himself a “private room,” only to design a sign inviting his brother in. I’ve seen my youngest curled under the crook of the other’s arm. They hurt each other constantly: wrestling, hitting, yelling, tears. They appear to me often to be physically linked.

Do we chase each other in the hope that we are not alone?

¤

I ran, I think, for the same reasons that I read. Lonely children are also often avid readers, and distance runners are a similar breed. We are creatures of introversion, experts in delayed gratification, fantasy, endurance. Like Frankenstein, we substitute physical pain for mental anguish, a sleight of hand that keeps our inner demons at bay. The “loneliness of the long-distance runner” notwithstanding, I wonder if the condition pre-empts the cause: if lonely people seek out running to reframe a pre-existing struggle as a choice.

And yet, some of my strongest friendships have been forged over running, just as they have been forged over books.

In the aftermath of my race, when friends and teammates applauded, I would feel slightly abashed. “You looked so strong!” they said. But I knew for much of the race I had been running automatically, drawn beyond a pace I wanted to be running because I felt connected to the woman I chased. I remember my surge, when it came, as feeling beyond my control, something perhaps mandated by that stranger on the sidelines, and something which I was fighting with every fiber of my thinking mind. I remember feeling almost angry as I watched myself close the space between myself and my competitor, from two steps, to one step, until I pulled ahead.

The only way I can explain my reaction is that the stranger reminded me I wasn’t the only one suffering out there; he took me out of my own head. How little in some ways I knew her; how vivid she remains. All that remained before me now was a stretch of grass. “What do you do when you fall far from help?” Vladimir asks the interloping tramp Pozzo. “We wait until we can get up,” he answers, “Then we go on.” But I could hear her just behind me, hurting, pushing me as she had pulled me before. We can never really outrun the presence of others; we are always, in some sense, going on. I told myself that once I finished, I could stop.