This is the last in a series of episode-by-episode reflections on Orphan Black season 5 (preview; episode 1 ; episode 2; episode 3; episode 4; episode 5; episode 6; episode 7; episode 8; episode 9). These pieces do not provide thorough plot summaries but do include spoilers; they assume readers have already been viewers. Responses via Twitter continue to be very welcome, and thanks to everyone for reading! Finally, please keep an eye out for an interview with Orphan Black co-creator Graeme Manson and science and story consultant Cosima Herter — coming soon to the LARB main site.

¤

From a certain angle, I’m a white male heterosexual whose life has been heavily shaped by evangelical Christianity.

That religious group voted for Donald Trump at a rate of four to one. I hear straight white males went the same way.

Why do I care about Orphan Black?

At the outset, my interest was only distantly related to religion or politics. I’ve explained in these pieces how productive is the show’s tension among biological inheritance, environment/culture, and individual agency. And by now it is clear to many that this Canadian series links incredible acting with daring writing and quality special effects, all with a small fraction of the budget enjoyed by Game of Thrones.

In previous reflections, I’ve expressed my appreciation for how the show critiques both fundamentalism and scientism. Both ideologies seek to assimilate real science, short-circuiting reason in the name of performed certainty. Orphan Black’s exposés range from frontal attacks on the cultic elements of the Proletheans and Neolutionists to satiric moments at Alison’s church and her community theatre. Epistemological fiction has long thrived in these modes, from widely recognized novels like Sinclair Lewis’s Elmer Gantry and Arrowsmith and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Maddaddam trilogy to lesser-known gems like Flannery O’Connor’s short stories and Craig Thompson’s graphic novel Blankets. There is similar power in films like The Big Kahuna (1999), Doubt (2008), and Spotlight (2015).

Ultimately, though, I think what really made me a fan of Orphan Black was the depth and variety with which the show represents the nature of love. The series finale gestures repeatedly to that commitment: the excerpt from Helena’s memoir, one last Cophine kiss, signs of Sarah embracing her mother’s call to “be still.” From a perspective influenced by feminist, queer, and liberation theologies as well as postsecular theory, Orphan Black is significant not only for rejecting religion that pretends certainty in the face of heartache, but also for modeling risk-taking faith, sober hope, and unassuming love, very often from the least pious sources. To be clear, I do not at all mean that it is “really” a Christian show (or the mouthpiece for any other religious tradition or ideology), but merely that it resonates far more deeply with the self-giving love of Gandhi and Mother Teresa than with many things done in Jesus’s name.

Let me explain a bit more. Every few years, I teach a course on the Hebrew and Greek scriptures in a public university setting, and without fail many students are shocked to hear Jesus’s harsh words for many of the devout. The religious experts in the gospels are concerned with ritual, doctrine, appearances, and hierarchy; he is all about presence, especially unstructured time with women, the poor, and the disabled. He applies the golden rule and they say, “What are you talking about? When did we ever see you hungry or thirsty or homeless or shivering or sick or in prison and didn’t help?” Again and again, the response is something like this: “Whenever you failed to do one of these things to someone who was being overlooked or ignored, that was me” (Matthew 25: 44-45, The Message). Or to adapt Cosima’s terms a couple millennia later, Your individualist religion isn’t enough. Quit ignoring the community around you. You have to love all of us.

Sadly, few American evangelicals are likely to appreciate how the penetrating love of Orphan Black harmonizes with that of their messiah. Imagine how Alison’s beloved neighbor Aynsley might respond if she were resurrected into a new life in the US South or Midwest, went to a more intensely Bible-thumping church, and someone proposed she watch the show. Well, first, it’s totally potty-mouthed and violent, and there’s sex on kitchen counters, and I just think that kind of thing only belongs on TV when we’re talking about who’s going to be president, OK? And the main characters are what, a murderer who thinks she’s an angel, a housewife who challenges her husband’s authority, this poor grad student deluded by academic elitism and clearly confused about her sexuality … and a drug dealer who can’t take responsibility for her daughter? You actually expect me to watch this?

I’m being sarcastic, but also serious: this white male heterosexual with a pre-doctoral seminary degree thinks so highly of Orphan Black partly because it powerfully challenges the hypocrisy that regularly characterizes one of the U.S.’s largest voting blocks. Yet it does so without unnecessarily condemning whole categories of people. Fittingly, given its commitment to challenging genetic determinism, it also defies cultural determinism. One moment it uncovers a nun’s cruel depravity; the next it entrusts another nun with an urgent plea for help. One moment a scientist reduces people to lab rats; the next another scientist fights back. I think this attentiveness to the potential good and evil across identity categories has much to do with the show’s success.

Without question, a large cross-section of its audience has found enormous encouragement in the way it dignifies female and LGBTQ characters, and last week I argued that the series treats the Leda clones’ experiences as inherently queer. But what about Orphan Black’s portrayal of men? In its 50th episode, Helena finally names her babies after two “real men,” Arthur Bell and Donnie Hendrix. Each is critical to Helena in his own way: Donnie developed a deep bond with the most instinctive, unfiltered sestra during her time living in the Hendrix home, while Art served as her backbone and cheerleader while she gave birth. Yes, these are supporting characters, but contra critical suggestions a couple years ago that Orphan Black might be subverting audience expectations for gender roles by making its male characters superficial, Art and Donnie are extensively developed dramatis personae. We may be left to imagine some parts of their stories, like the implication when Art arrives at Alison’s home that he has adopted Charlotte as a second daughter, caring no more about her skin color than Helena did about her impromptu midwife’s. But many parts are substantially fleshed out, like Donnie’s adaptation to the new Alison.

When his wife returns from her time alone in California, she has undertaken a dramatic change (even if her objection about the clones’ skin color in the finale suggests that it will necessarily be gradual). Donnie received no warning about the new, purple-haired Alison, her determination to stop micromanaging him, or her interest in shifting from obsessive craftiness to unscripted musicality. His reactions are about as open-minded as one could hope, if also cautious: who is this woman who doesn’t care if a painting sits one inch further left or right? Yet late in episode ten, we see him getting the hang of it. The scene in which he peels off his shirt and starts a mock striptease routine for Alison will delight fans of season three’s underwear twerking, but it matters for more than its comedic value. It’s one more reminder of how the show has overturned stereotypical treatments of the female body, turning back a consumerist gaze on the men who perpetuate it. (Incidentally, I think it cements the link between this biotech thriller and Eleonore Pourriat’s brilliant 2010 short, Oppressed Majority.)

In other words, Orphan Black’s male characters are not superficial, but they are sometimes subjected to the same evaluation usually reserved for women in swimsuit calendars. Donnie’s dance for Alison reverses the typical act of objectification, but without such a gaze. She is amused, but she is with him, not consuming him. This is an act of love, performed in good humor and with significant humility on the part of both the character and the actor. What it recalls for me, in fact, is not just the bedroom dance scene two seasons earlier, but the boldness with which a scantily clad Felix has often attacked his paintings. Again, the courage of both character and actor here are indictments of the exploitation so common to both the male and the heterosexual gaze. Like Jordan Gavaris’s and Kristian Bruun’s performances across this show’s five seasons, Felix’s artwork is a gauntlet tossed at the feet of patriarchy and homophobia.

To conclude, for now: Orphan Black invites us to change our lives. Its finale offers solace that when standing up to abuse is costly, and even when we run out of obvious enemies but still “don’t know how to be happy,” we are not alone. For those who do their best to resist some of the many structural injustices built into our culture, this show has been a breath of fresh air. For those who try to make faith justify exploitation, though, Orphan Black is more like an oxygen tank to the face.

¤

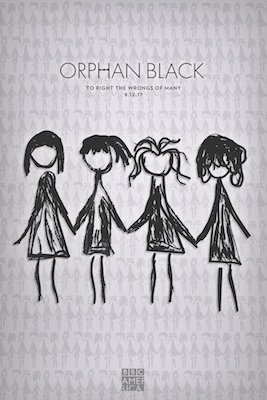

Orphan Black’s final season (10 weekly episodes) began Saturday, June 10, at 10/9c on BBC AMERICA.