This is the second in a series of episode-by-episode reflections on Orphan Black season 5 (see the preview article here and episode 1 response here). These pieces do not recap plots but do include spoilers; they assume readers have already been viewers. I will also use this chance to thank BBC America for advance access, but also to note that upon each essay’s submission, I have not watched beyond the relevant episode (surprises await all of us!). Finally, as before, please don’t hesitate to extend the conversation in the comments or via Twitter.

¤

“You’re gonna have to let go.”

Sarah is dreaming as Orphan Black season five episode two begins, but her daughter’s words illuminate both the path ahead and the one already traveled. Most obviously, Sarah will soon be asked to let go of her daughter, with Kira choosing the seeming stability of life with “Auntie Rachel” over another flight into the unknown with her true family. But I want to focus on a second significance of Kira’s words in this episode: Sarah must also let MK make a far less revocable choice, one that leads directly to her death.

How do we deal with such losses, even when they are voluntary sacrifices aimed at protecting others? Most of us tend to hold on for dear life. Let your daughter depart with a woman who has previously kidnapped her, who has demonstrated so little capacity for love? Leave your sister, even one you only barely knew, in the awareness she is about to confront a known murderer with little more than a poor disguise and a kitchen knife? No, thank you.

Orphan Black says differently. The show has never pretended its clone sestras always make wise or admirable choices (see: “Compacters, Kitchen Sink”). But it has also repeatedly granted these women the space to make mistakes and to learn from them: trial and error, then try, try again. Unlike signing up with Dyad, being part of Clone Club does not rely on legal contracts. Certainly, there has often been sibling pressure — time to step up and pretend to be me, sestra! — but if you slam closed your laptop on a videoconference or try to party yourself into oblivion, the relationship isn’t over.

Admittedly, before MK’s final scene, Sarah diverts to Felix’s loft and seeks to change her sestra’s mind, even as Ferdinand draws nearer and the clock ticks on her escape plans with Kira. But the conversation is two-way. Sarah listens even as she seeks to persuade; she accedes to MK’s insistence on trading clothes even as she tries to imagine another way. Once convinced that her sestra’s resolve is firm, Sarah regretfully lets go.

Of course the immediate result is horrible. Ferdinand epitomizes the spoiled child, the narcissist, the man who seeks titillation rather than affection. But even as fans lament MK’s death, we should consider the alternative that Orphan Black rejects. In the larger context of MK’s and Sarah’s stories, it would have been hugely dissonant for Sarah to have pressed her way any further. It makes no sense to claim to love someone without granting her a truly independent agency. There is no Code of Clone Ethics, but if there were, it would prohibit coercion. That is left to Dyad, Topside, and Neolution.

Even the exceptional moments prove this rule. Rewind to season four, episode four, and remember how “the girl in the shadows” nearly killed Ferdinand, a scene that season five has now skillfully inverted. Earlier, MK drew Ferdinand to Beth’s apartment, enticed him onto a booby-trapped chair, drained his offshore accounts, and would have left him to an explosive end. But Sarah and Mrs. S intervened, saving Ferdinand not out of altruism, but for his potential usefulness.

That was a devastating moment for MK. She had likely looked forward not only to destroying Ferdinand, but also Beth’s apartment, the scene of an abandonment MK could never fully understand. Especially when we ponder her backstory as Veera Suominen via Heli Kennedy’s canonical Helsinki comic books, MK becomes a young woman desperate for friendship. That medium has Veera acknowledge the unique struggles that come with Asperger Syndrome (reclassified since 2013 as autism spectrum disorder), a detail the show never makes explicit, but which certainly fits MK’s speech patterns, social hesitations, and gifts for rapidly synthesizing enormous amounts of data. In short, we must realize that when MK lost Niki, her friend in Helsinki, Beth took on similar significance, making Beth’s choice to die doubly painful.

Like Sarah arriving at Felix’s apartment in season five, MK tried to interrupt Beth just before her fatal trip to the train station. Beth’s response to MK’s desire to help in that moment now sounds painfully familiar: “You can’t. It’s over. We’re done. I’m done. I screwed it up. We can’t fight this anymore, Mika.” Then, after a pause, more quietly: “You need to drop all this. Go back into hiding. Drink iced tea, play video games, whatever. Just stay hidden.” And in a whisper, with a hug: “Watch the others for me.” There is still a note of hope within this apparent capitulation, just as there is when MK tells Sarah that she must fight for something even bigger than Kira’s safety.

In season five, MK is exhausted, just like Beth was. She has nothing more to give. When Sarah urges, “you’re not giving up,” MK responds, “I told you, I’m too tired, Sarah. I’ve been running my whole life.” Unlike MK’s hurt confusion in response to Beth, however, Sarah begins to understand. It might help that this is not their first such conversation; Sarah had her way when her intervention saved the man who is now moments from killing MK. Previously, Sarah had insisted, “I want revenge too, but we’re not going to do it like this”; this time, she lets go. There is still deep regret — both characters “wish it could have been different for us” — but Sarah also respects MK’s wishes and the sacrifice she believes herself to be making for Kira.

Even in its painfulness, this move defies everything about Ferdinand. Once he realizes that it is Veera in his grasp, not Sarah, his perversion reaches a new low. Fully aware that he is enacting the same “revenge fantasies” he accused MK of desiring in Beth’s apartment, he simultaneously “finish[es] Helsinki” and pours out the rage of a jilted lover. In this state of double consciousness, Ferdinand rejects (but thereby underlines) one of Orphan Black’s foundational theses, that love is antithetical to use. Contra the show’s refreshing epigenetic emphasis on the differences that exceed biological inheritance, he embodies the worst kind of genetic determinism. Ferdinand would blur Rachel and MK back into a single objectified organism, one good for only two purposes: sex and violence.

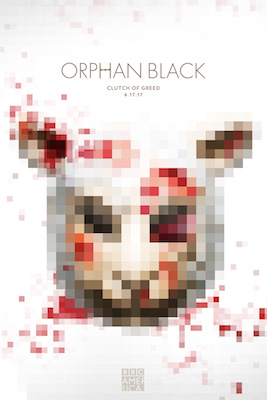

Two more thoughts in stepping back from “Clutch of Greed,” a title that perfectly describes Ferdinand’s desperation. First, as he thrice screams “you hurt me” at the Rachel he pretends is under his heel, he is also the foil for everything the show teaches about how to grieve. This has long been one of Orphan Black’s strengths: confronting pain rather than fleeing it, acting on loss rather than passively succumbing. Think of Paul’s face as he looks at Sarah for the last time and as the grenade falls from his lap. Remember the defiance of Kendall Malone: “No tears, Cosima. These shites aren’t worth the salt.” Even when there are no moves left on the board, the show demonstrates the possibility of owning one’s circumstances, of being defeated but not broken.

Lastly, let’s hold onto Mika’s other parting gift, her insights about one P.T. Westmoreland. As indicated last week, I believe Orphan Black is preparing to expose once more the dark underbelly of Neolution, the violent costs of its eugenic vision. The show’s sophistication makes it capable of both honoring Darwin and challenging those who would artificially accelerate the tortoise of natural selection without carefully counting the cost. This is what Mika finds most crucial to share with Sarah in their last seconds together: “It’s Westmoreland, his story is the key to all of this. But it doesn’t add up. Where did he build his power? What is he doing with it? He’s hard to trace, hidden deep. I’ve been trying to find him. New privacy networks, cryptocurrency marketplaces. There’s no data. There’s not enough data. We need more data.”

We do need more data. Yet Orphan Black has taught us that information alone is insufficient. Knowledge is invaluable, but we also need sheer intuition, leaps of faith in our sestras. Leaps that include finding the courage to let them go — then to live in their light.

¤

Orphan Black’s final season (ten weekly episodes) began Saturday, June 10, at 10/9c on BBC AMERICA. Click here to read the episode three reflection.