On January 3, 1889, in the throes of a manic episode, Friedrich Nietzsche left his lodgings in Turin, walked a short distance across a nearby square, and then halted. Seeing a horse being flogged by its owner, he threw himself towards the animal and embraced it. Breaking into tears, he slumped to the floor. He was almost arrested for disturbing the peace, but was rescued by his landlord and was taken back home and to bed. The remaining 11 years of his life were spent under care, and under the spell of profound madness.

So goes the story of Nietzsche’s collapse in Turin, at least as far as conventional wisdom has it. The above is a fairly uncontroversial telling of the episode, which is generally considered an important one within his intellectual history: it marks a definitive moment, between great philosopher and broken mind. Biographers and historians tend to place particular emphasis on the role of the horse; it appears in nearly all scholarly tellings of Nietzsche’s life, and surfaces and resurfaces across literature such as narrator’s anecdotes in Milan Kundera’s Unbearable Lightness of Being. The episode also inspired a 2011 film, The Turin Horse. Strange, then, that there is actually very little evidence that there ever was such a horse. And stranger still that the episode seems to have been torn from the pages of a writer revered by Nietzsche: Fyodor Dostoevsky.

The passage in question occurs early on in Dostoevsky’s great work Crime and Punishment. Raskolnikov, who will imminently butcher two old ladies with an axe, is anxiously laid up in bed. In a scene that foreshadows the guilt-ridden and hallucinatory fits that will plague him after the murder takes place, he falls into a disturbing dream. Raskolnikov sees himself as a young boy, walking through a provincial town with his father. Outside a pub, a drunken rabble surrounds a weary old horse, hitched to a weighty cartload that it cannot possibly pull. To the delight of the cheering mob, the horse is beaten by its owner (“so brutally, so brutally, sometimes even across the eyes and muzzle”). Men climb into the cart to weigh it down further, and the owner continues to whip and to shout “Gee-up!” When someone speaks up against the violence, he merely yells “My property, my property!”

Raskolnikov, in the voice of a child, pleads with the men to stop. Crying, he runs forward and looks the horse directly in the eye, and in doing so, is caught by a lash from the whip. As the cruelty escalates and the horse collapses, it becomes clear that it will die. Raskolnikov throws his arms around the bloodied muzzle and kisses it around the eyes, calling in vain for the barbarism to stop. His father scoops him up and drags him away from the horse, against his will, and suddenly Raskolnikov awakes, cold and sweating. He understands the significance of the dream, and understands that he himself was at once the child, the flogged horse, and the man with the whip. Nevertheless, he rises, dresses, and prepares to commit murder.

The horse episode held special significance for Dostoevsky, originating, as it did, in his own life experiences. In his diaries, under an entry relating to the “Russian Society for the Protection of Animals,” Dostoevsky offers an illustration of the manner in which our relation to animals reflects our ethical relation to other humans. He recalls that at age 15, he, his father, and his brother were journeying on the road when they saw a man in military uniform, having freshly swallowed down a glass of vodka, return to a cab and immediately and senselessly set about beating his driver around the back of the head. The cabbie, in turn, mercilessly begins to flog his horses with a “terrible fist”: “the coachman, who could barely hold on because of the blows, kept lashing the horses every second like one gone mad; and at last his blows made the horses fly off as if possessed.” The young Dostoevsky’s own cabbie, shaking his head at the scene, tells him that this was quite usual, and that “the lad, perhaps, that very day will beat his young wife: ‘At least I’ll take it out on you.’” Dostoevsky serves this up as a stark example of how violence breeds violence, and injustice breeds injustice. The horse story is, for him, “something that very graphically demonstrated the link between a cause and its effect. Every blow that rained down on the animal was the direct result of every blow that fell on the man.”

Throughout the 1866 composition of Crime and Punishment, the horse story was always intended to serve as part of Raskolnikov’s intellectual development; indeed, in Dostoevsky’s notebooks of the period, he attempts to find a place for the horse story no less than six times in the structure of the novel. By the writing of the novel, when Dostoevsky was 44 years old, he came to view the story as a formative memory: “My first personal insult, the horse, the courier.” Fittingly, then, a similar episode resurfaces in Dostoevsky’s final novel The Brothers Karamazov, in the chapter “Rebellion.” In that work, a story is told of a horse that cannot pull its cartload; the owner “beats it, beats it savagely, beats it at last not knowing what he is doing in the intoxication of cruelty, thrashes it mercilessly over and over again.” We are told that the story is “peculiarly Russian.” Surprisingly, we also discover that these words are adapted from “lines from Nekrasov” — a reference to the poem “O pogode” (“About the Weather”) by Nikolai Nekrasov, in which a “hideously lean” horse is beaten to death in front of a laughing mob.

Nekrasov’s poem was composed after Crime and Punishment — therefore Dostoevsky’s own horse seems real enough, even though he would later draw on another writer’s image of a beaten animal. But was Nietzsche’s horse not also Dostoevsky’s? Nietzsche was 44 years old in when he suffered a collapse in Turin — coincidentally the same age as Dostoevsky had been when he wrote Crime and Punishment. He had been living a transitory existence for some years, having all but excluded himself from positions at German universities due to his irreligious thought and his provocative writings. In Turin his hosts were the Fino family, and in their house, in the extraordinarily productive year leading up to the famous incident with a horse, Nietzsche wrote what are remembered as some of his greatest works. But the year was also marked by his increasingly erratic behavior; he would sing and play for hours at a piano, often tunelessly; he would, allegedly, dance boisterously in the nude around his room; the Finos even discovered torn and discarded money in his waste-paper basket. In the view of his landlord, the professor was showing worrying signs of mental decline.

The truth is we know very little about what occurred on that fateful January day in 1889. Undoubtedly Nietzsche was found in the street, and there are multiple firsthand accounts that detail Nietzsche’s subsequent mental decline and his spell in a mental asylum shortly after. But there is only a single source that brings a horse into the picture. It comes from an interview with the landlord, conducted by an anonymous journalist after Nietzsche’s death in 1900 — 11 years after his walk through Turin. The report reads:

One day when Mr. Fino was walking along the nearby Via Po — one of the main streets of Turin — he saw a group of people drawing near and in their midst were two municipal guards accompanying “the professor.” As soon as Nietzsche saw Fino he threw himself into his arms, and Fino easily obtained his release from the guards, who said that they found that foreigner outside the university gates, clinging tightly to the neck of a horse and refusing to let it go.

The story of the Turin horse was thus told 11 years after the event it purports to describe, by an unnamed reporter, who recounts a version of events spoken to Nietzsche’s landlord by an equally nameless police officer. The narrative is thirdhand hearsay in its sole original form.

None of this, of course, has stopped the story being told. Here is a selection of excerpts from five of the more well-known accounts of Nietzsche’s life:

“On 3 January 1889 or thereabouts he tearfully embraced a mistreated nag in the street.”

“With a cry he flung himself across the square and threw his arms about the animal’s neck. Then he lost consciousness and slid to the ground, still clasping the tormented horse.”

“Nietzsche threw his arms around the horse’s neck, tears streaming from his eyes, and then collapsed onto the ground.”

“As Nietzsche fell on the pavement, he threw his arms around the neck of a mare that had just been flogged by a coachman.”

“Nietzsche had just left his lodgings when he saw a cab-driver beating a horse in the Piazza Carlo Alberto. Tearfully, the philosopher flung his arms around the animal’s neck, and then collapsed.”

Given the circumstances, it is easy to imagine that Nietzsche may well have been weeping — thus the addition of his tears to many of the versions seems broadly permissible. But note that there is no coachman whatsoever in Fino’s version of events, and that the very suggestion that the horse might have been suffering at the hands of anyone has trickled into the narrative during its retelling. (Fino doesn’t actually mention a collapse either, but letters circulating amongst Nietzsche’s friends at the time make it clear that a fall took place.) The central image of his life that has proven so tenacious, that of the weeping Nietzsche embracing a horse, is perhaps the most difficult to prove.

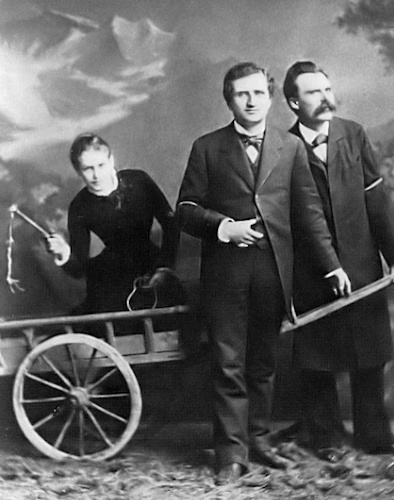

There are several reasons why this story might have become so ingrained in the popular understanding of Nietzsche. For one, he provides his own links between his pre-madness biography and the works of Dostoevsky. Less than a year before the incident, he wrote, in Twilight of the Idols, that Dostoevsky was “the only psychologist, incidentally, from whom I had something to learn.” The lesson Nietzsche took from Dostoevsky was that criminals represent strong minds under sickness — he must surely have been thinking of Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment. And around the same time, Nietzsche was having his own dreams of horses. He details one in a letter of 1888: “winter landscape. An old coachman with an expression of the most brutal cynicism, harder than the surrounding winter, urinates on his horse. The horse, poor, ravaged creature, looks around, thankful, very thankful.” Nietzsche tells his correspondent that the repulsive dream nearly stirred him to tears. Perhaps Nietzsche did have horses on his mind when he stepped into the square on that January morning, and was drawn by some impulse towards one. Perhaps the sight of a horse being flogged really did raise in him the image of Dostoevsky’s pitiful nag, and he felt a peculiar compulsion to complete the scene. Or maybe it is Nietzsche’s students and scholars who have flooded the gaps in Fino’s account, and found literature in the life of the philosopher.

This is an idea that is especially tantalizing. It has been convincingly argued that Nietzsche’s works amount to a philosophy of aestheticism — that he commands us to live life as one would write literature. He writes, for instance, in The Gay Science, that “One thing is needful. — To ‘give style’ to one’s character — a great and rare art!” If Nietzsche advises, above all, that we should cultivate our lives and our selves as we would create a work of art, what might it mean for his own life to so neatly replicate a literary work? And how interesting, for philosophers, that this particular act of mimesis marked his departure from sanity. In 1888 he had written Ecce Homo, a philosophical work resembling biography, subtitled “How One Becomes What One Is.” Might it be that, in embracing a horse in the manner of Raskolnikov, he was writing one last chapter to his life and work?

There is also the fact of the symbolic potency of the horse. For Dostoevsky, in Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov, as well as in some of his own life experiences, the horses represented the shallows of human cruelty, but also the depths of empathy. (I am reminded of lines from William Blake’s “Auguries of Innocence”: “A Horse misused upon the Road / Calls to Heaven for Human blood”.) If you are capable of loving, and of feeling and sharing the pain of a creature as pitiful as a horse, then surely only love for mankind can follow. It might be tempting to over-emphasize the role of Nietzsche’s horse in his life precisely because we feel forced to read it as a focal point of compassion. Nietzsche, who directed his philosophy against Schopenhauer’s conceptions of pity and empathy, would appear to be bearing witness to the cracks in his own reasoning if he himself, in a moment of radical pathos, is brought trembling and weeping to his knees by a beaten nag. (It is hard to say whether it helps or hinders the thesis of compassion that Nietzsche, in his final years of madness, was supposed to have unendingly repeated a few terse phrases, including “I do not like horses.”) It is tantalizing for his readers to imagine that, by embracing a horse, he was ending his career as a philosopher and writer as a spectacular failure — he was confessing, not in words but in action, that we cannot slip so easily out of the confines of compassion. “Human,” he might say; “All too human.”

Milan Kundera, in a late chapter of The Unbearable Lightness of Being, seems to opt for this interpretation of the episode when he writes that “Nietzsche was trying to apologize to the horse for Descartes.” Where the philosopher René Descartes claimed that animals are effectively soulless machines, existing only for the use and benefit of mankind, Nietzsche, thinks Kundera, came to re-soul the horse — to see in it affinity with his own being. Nietzsche’s readers who share this view seem to want to believe he threw his arms around that horse, in part because it can be seen as a final flourish to complete his life’s writings (and the writing of his life), but in part because it seems so fatally to contradict large areas of his thought. True or not, it is now part of how we understand his life, and it is now a rock, easily thrown by his critics, which might knock down those structures of his thinking we find might less palatable today. Certainly, anyone tempted to interpret the story of the Turin horse as a story about understanding others will find fuel in lines Nietzsche had written that same year, about another overburdened equine: “Can an ass be tragic? — Perishing under a load you can neither bear nor shed?…The case of the philosopher.” The ass and the philosopher, united in their failure to bear a load — the unbearable heaviness of being.