Sasha Abramsky will be reading from his book on Thursday, October 1 at 7 pm at Book Soup Bookstore, 8818 Sunset Blvd. West Hollywood, CA 90069

During 1968 and 1969 I spent a year in London. I was supposed to be studying politics and sociology, but I spent more time at anti-war rallies and protests, at folk-music clubs and concerts, writing articles, and traveling around England and Europe, than I did in class. On a whim, however, I decided to take a course in Jewish history at University College. The catalog indicted that the course would be taught by a professor named Chimen Abramsky, whom I had not heard of before.

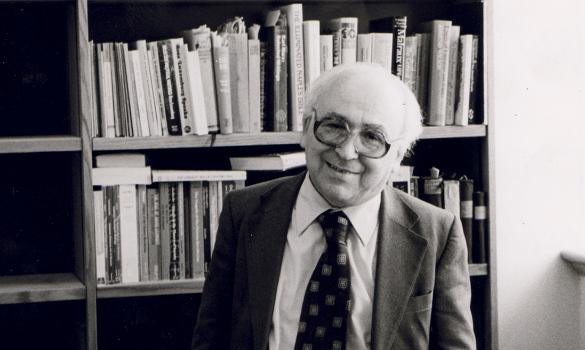

Despite my general indifference to academic matters, I rarely missed a session of Abramsky’s course, which met in a tiny classroom. Abramsky was in his mid-50s but to me he appeared much older — perhaps because I was only 20, but perhaps also because he had an Old World look about him. He spoke in a thick Russian-Yiddish accent, which required students to listen carefully to his lectures, which he often delivered while sitting in a chair, dressed in a rumpled suit and tie. Abramsky was a tiny man who seemed quirky, eccentric, impish, and brilliant.

I remember the aura more than the specific content of the course. I was not educated enough in Jewish history, or history in general, to appreciate what he had to offer. I should have taken some more basic Jewish history courses — or read about it on my own — before venturing into this class. Intimidated by his erudition and embarrassed by my own ignorance, I unfortunately didn’t bother to talk with him after class or to learn anything about him or his life outside the classroom. Still, I was mesmerized by his presence, almost as if he was a performance artist.

A few years ago, at a conference of activists and academics, I met Sasha Abramsky, a British writer, transplanted to the United States, who has authored several excellent books, including Inside Obama’s Brain and The American Way of Poverty: How the Other Half Still Lives. I asked Sasha if he was related to the professor I had taken a course with decades earlier. It turned out that he is Chimen’s grandson, and he told me about his grandfather’s fascinating life. From Sasha I learned that Chimen (pronounced “Shimon”) was an extraordinary historian and bibliophile, a world-renowned student of Marxism as well as Jewish history, and the center of a global network of scholars and activists.

Shortly after Chimen’s death in 2010, Sasha penned a wonderfully warm and evocative recollection of his grandfather in the British newspaper, The Guardian. Now he has expanded that essay into a book, The House of Twenty Thousand Books, which brings his grandparents and their world to life. Published last year in England, it has just been released in the United States by New York Review Books. Abramsky has also produced a five-minute video that is worth watching on its own and will surely whet your appetite to read the book.

Chimen Abramsky was born in Minsk in 1916, the son of Yehezkel Abramsky, an esteemed Orthodox rabbinic scholar. Yehezkel arranged for Chimen to be schooled by private tutors at home, where he learned Yiddish, Hebrew, and Russian. In 1929, Stalin’s police arrested Yehezkel in Moscow and sent him to Siberia for treason, although his real crime was his opposition to the regime’s persecution of Jews. Thanks to a lobbying campaign by Jews around the world, Yehezkel was released, and in 1932 moved his family to England, where he became a prominent rabbi.

Chimen had no interest following in his father’s religious footsteps, but he absorbed his father’s love of books and scholarship. Arriving in London during the Depression, he took English lessons at Pitman College and was quickly drawn to the city’s circle of secular Jewish immigrant intellectuals, artists, and activists, as well as the radical students at the London School of Economics. Thus began his lifetime love affair with the study of Jewish history and culture as well as Marx, Marxism, and socialism.

In 1936, Abramsky went to Palestine to attend Hebrew University, where he became deeply involved in socialist politics. The campus ideological battleground was so intense that one day Chimen was beaten up by Yitzhak Shamir, then a leader of the right-wing Irgun faction and later Israel’s prime minister.

Abramsky returned to London in 1939 to visit his parents but was trapped by World War II and unable to return to Israel. He found a job at Shapiro, Vallentine & Company, London’s oldest Jewish bookshop. In 1940 he married the owner’s daughter, Miriam Nirenstein, and both became active members of the British Communist Party. He joined the CP in 1941 after the Nazis invaded Russia in June 1941, and became a leader of the CP’s large Jewish wing and editor of its publication, the Jewish Clarion. Miram left the CP in 1956 (after the Soviet invasion of Hungary), but Chimen remained a member for another two years, finally acknowledging the atrocities that left many leftists disillusioned with Communism.

Although Abramsky left the Communist Party, he never left the left. Moreover, his left-wing views didn’t thwart his remarkable entrepreneurial skills. The bookstore provided him with an opportunity to acquire a personal library of 20,000 volumes, primarily books on socialism and Judaism. His collection included first editions of Spinoza and Descartes, books that belonged to Leon Trotsky, manuscripts and letters by Voltaire and Marx, and even Marx’s membership card in the First International. He developed a global network of book collectors and, with a keen eye for a good deal and a remarkable ability to authenticate and judge the value of a book, made a reasonable living in the book business. Sotheby’s hired him as a consultant on rare books. He played an important role in the rescue of several Torah scrolls in Czechoslovakia that had been confiscated by the Nazis.

He may have enjoyed the travel and the wheeling and dealing but at heart Abramsky was a scholar. While he thrived as a bookseller and manuscript expert, he pursued his scholarly activities on his own, having no degrees or institutional affiliation. That changed after some noted British academics — including E.H. Carr, James Joll, and Isaiah Berlin — encouraged Abramsky to teach. After his book, Karl Marx and the British Labour Movement (co-authored with Henry Collins) came out in 1965, he was invited, through Berlin, to teach at Oxford. The next year, at age 50, he was invited to assume a newly-created lectureship in modern Jewish history at University College-London (UCL), which is where I encountered him in that small classroom. In 1974, he became head of the UCL’s department of Hebrew and Jewish studies, keeping the position until he retired in 1983. Twice he accepted invitations to teach in the United States, holding visiting professorships at Brandeis and Stanford.

He was widely influential through his writings, his mentorship of generations of scholars, and his ability to bring people together at dinners and meetings at his home. His friends included some of the world’s leading left-wing historians, including Christopher Hill, Eric Hobsbawm, and E.P. Thompson. In 1989, his students and colleagues published Jewish History: Essays in Honour of Chimen Abramsky, a reflection of his impact and inspiration. In 2012, a donor established the Professor Chimen Abramsky Scholarship for undergraduate students at the Department of Hebrew and Jewish Studies at University College-London.

The House of Twenty Thousand Books is part history (about his grandparents’ background and their social, political, and intellectual milieu) and part memoir (about how Sasha absorbed that world of Marxism and matzo balls). He describes the Abramsky home on Hill Way in London (not far from Highgate Cemetery, where Karl Marx is buried) as an ongoing salon that attracted socialists and Jewish intellectuals who came to eat, exchange ideas, enjoy each other’s company, and examine Abramsky’s huge collection of rare books, which filled every room and staircase in the house.

Abramsky was both generous and stingy about sharing his remarkable collection of books. He allowed scholars and fellow bibliophiles to visit the house to examine his books, but only those who Abramsky considered serious enough to merit entry in his working library. Although each room was dedicated to books on a different subject, his “system” was quite disorganized and he lacked the time, money, and will to turn the chaos into order and to adequately protect some of the rarest and most valuable books from the elements.

To retrieve his grandfather’s story, Sasha had to excavate the book collection, review the writings of Chimen, his correspondents, and other scholars, and interview family members as well as his grandparents’ friends and colleagues. He writes with both love and respect, an understandable nostalgia, and with sympathy, if not total agreement, with his grandfather’s intellectual and political preoccupations. His grandmother, an accomplished social worker and political activist, gets less attention than she deserves. Abramsky mostly focuses on her cooking and homemaking skills, the hostess at the endless gatherings of family, friends and colleagues from around the world. Although his grandparents were secular radicals, they kept a kosher home, a legacy of his upbringing and his unwillingness to completely alienate his father, the strictly religious rabbi.

The House of Twenty Thousand Books tells the story of a world that no longer exists. I missed my opportunity to get to know Chimen Abramsky personally when I had the chance. But now others will get to know this extraordinary man through the eyes of his grandson.

Peter Dreier teaches Politics and chairs the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College. His most recent book is The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame (Nation Books, 2012).