“Truth. It’s vital to democracy. No alternatives, just facts. Get up to 40% of the Times subscription of your choice.” The New York Times has been running this advertisement since Trump took office, and it says it all: not just about the state of liberal democracy, but also about its limits.

On the one hand, the media’s campaign for truth certainly is vital to democracy: it reasserts the commitment to sustaining alive whatever remains of America’s capacity for rational public deliberation. Without it, liberal politics will wane and die. But we should also notice with suspicion just how eager news outlets have been to declare a holy epistemological war. The present crusade in defense of facts represses much deeper anxieties about truth and politics; ones that concern not just Trump, but the forces making him possible in the first place.

“Take care of freedom, and truth will take care of itself.” Richard Rorty liked repeating this slogan to capture the essence of liberal politics. The idea is to radicalize Jeffersonian toleration, or Enlightenment state neutrality: just as the state ought not impose a religion on its citizens, it has no business promoting a specific conception of the Good. Just as politics must be freed from the authority of God, it must be liberated from the authority of truth: not merely factual truth — this is just the point — but truth understood as some metaphysical conception that could ground universal norms. While America’s liberal media is fighting for facts, American liberalism has rejected truth much more comprehensively.

The present crisis of liberalism is especially complex because once truth is excluded from politics, patriotism quickly replaces it as the anchor of public norms. That is, instead of drawing on universalist metaphysical grounds — say, human nature — liberals can only vindicate their position by reference to who they are. Speaking with Rorty, they justify norms by reference to something “local and ethnocentric”; their “national pride, their own community and culture.” For such liberals, what counts as politically acceptable or gets excluded as obscene can only be vindicated by reference to the “body of shared belief which determines the reference of the word ‘we’.”

For years, Rorty’s patriotic we-liberalism has informed the rejection of America’s so-called “identity liberalism.” Identity liberals, the argument goes, have given up on the patriotic locution “we Americans” or “we the people” as an anchor of politics. As a result, instead of promoting pragmatic political agendas that could answer to the urgent needs of America’s middle class, they retreat to a spectator’s armchair: to sophisticated philosophy departments, deconstructing American society into an infinite celebration of difference. In Achieving Our Country, a once-infamous treatise that today gets quoted and re-quoted as a rediscovered oracle, Rorty urged the left to ditch identity liberalism and reclaim a Rooseveltean patriotic politics: otherwise, “something will crack”; Americans will “start looking around for a strongman to vote for – someone willing to assure them that, once he is elected, the smug bureaucrats, tricky lawyers, overpaid bond salesmen, and postmodernist professors will no longer be calling the shots.” Most readers who have tweeted this now-famous Prophetic Rorty Quote overlooked that it is not at all Rorty’s. He brings it from Edward Luttwak.

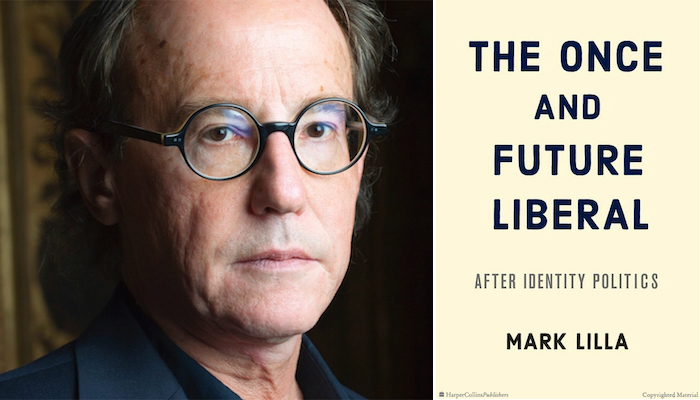

Mark Lilla’s The Once and Future Liberal, extended from his controversial New York Times Op-Ed on the end of identity liberalism, never mentions Rorty by name. In itself, this is nothing to complain about; Lilla masterfully sets a dialogue in this short book with a whole pantheon of authors that he does not mention, including, other than Rorty, Foucault, Butler, Schmitt, Honneth and Houellebecq, to name but a few. But in Rorty’s case things are different: anyone who has read Rorty and not just Luttwak would have to wonder what advance The Once and Future Liberal offers beyond Achieving Our Country. Or more interestingly: what answers if any Lilla could provide to the political-conceptual mess that has entangled Rorty’s post-identity we-liberalism at least since the nineties.

According to Lilla, American political history in the last century can be told as the rise and fall of two political “dispensations,” each providing its own “catechism” and inspiring a different vision of “America’s destiny.” First, a Rooseveltean era, stretching from the thirties’ New Deal to the Civil Rights movement in the late sixties: it promoted a political agenda based on citizenship, solidarity and collective duty to protect each other’ “fundamental rights.” Second, a Reaganite era, consisting not in liberal but in libertarian politics. Undoing everything that Roosevelt had been about, it stressed individualism over solidarity and entrepreneurship over citizenship or collective action. Fundamentally anti-political, it is only appropriate that this libertarian era would now come to a close with an “opportunistic, unprincipled populist.”

Liberals did not spend the last forty years developing an alternative vision for America’s “shared destiny.” Instead, they joined Reagan’s decomposition of America into anti-political “elementary particles,” turning liberal politics itself into a stage for “pseudo-political” drama where action has been replaced by personal “self-expression.” This “narcissistic” approach could not but alienate the large majority of American citizens. Winning elections, however, is about commonality, not difference. Wittingly or not (“there is a mystery at the core of every suicide”), identity liberals thereby handed the country over to Trump.

Anyone familiar with current sentiments on America’s left-liberal circles must admit that this is a story to which one should, to the very least, lend an ear. A striking example of the identity predicament in whose grip we find ourselves is the controversy that erupted last March over “Open Casket,” a painting by the artist Dana Schutz. Depicting the mutilated body of Emmett Till, an African American child who was lynched by white men in 1955 Mississippi, the painting was displayed in New York’s Whitney Biennial and sparked intense protest. Schutz is white, and has been accused of exploiting “Black pain” for her art. The work’s “subject matter,” a petition contended, is “not Schutz’s; white free speech and white creative freedom have been founded on the constraint of others, and are not natural rights.” Clearly, identity liberalism has driven American liberals into a very illiberal corner. An analogous position in Germany would suggest that Gerhard Richter’s abstract depictions of Auschwitz-Birkenau should be destroyed as anti-Semitic appropriation of Jewish suffering.

Open Casket has since then been displayed with Schutz’s written explanation: she cannot “know” what it is like to be “Black in America,” but she does “know what it is like to be a mother” — and “Emmett was Mamie Till-Mobley’s only son.” In other words, Schutz decided to subscribe to the identity politics of her critics — she could have added her name to their petition just as well. Assuming that art’s function is to transgress — undermine what we know in order to enable an experience of what we can’t — the painting has been through Schutz’s explanation successfully destroyed.

More specifically: by writing on the painting what the author, given who she is, can or cannot know, identity liberals have reduced art back to the facts. This is damaging, because art is supposed to overcome a cheap factual conception of truth: transcend the unsatisfactory alternative between facts and alternative facts; allow us to touch an experience irreducible to factual knowledge that’s indispensible for meaningful political life.

The only way to salvage Schutz’s remarkable painting from her explanation is to insist that the author, like God, is dead; that artists have no authority over the truth that’s expressed in their creation. But within the horizon of identity liberalism, the author is anything but dead: everything seems to be about the author. It is not too much of a stretch to suggest that identity liberalism is only pseudo-political because it undermines art by binding it to what an artist has the right to know.

Lilla doesn’t comment on “Open Casket,” but he correctly diagnoses the politics behind it as a “damning” miscalculation. “In a democracy, the only way to meaningfully defend [minorities]” is to “win elections,” he writes. In order to do that, one will have to build commonalties — speak to Americans as Americans. Identity liberalism “does just the opposite,” leaving young African Americans and other exposed groups that liberals profess to care about more rather than less vulnerable.

At least one author has responded to Lilla’s original Times Op-Ed by dismissing him as a “white supremacist.” Reactions of this sort have only served to reinforce his position, expressed in the book, that liberals who are focused on identity have become obsessed with the purity of propositions and not interested enough in their truth. Lilla’s multiple critics on the left would do well to notice that this white supremacist’s main argument, when translated into political action, is a call on the Democratic Party to backpedal from Clinton to Sanders, who is hardly insensitive to racial and gender injustice.

But if we do take Lilla’s challenge seriously, deeper questions arise about the alternative politics that he offers. The Once and Future Liberal prescribes civic liberalism that seems very much like Rorty’s patriotic variety: there is “no liberal politics,” we are told, “without a sense of we”; the only answer to the consummation of Reaganism through Trump’s demagogy is a recourse to “something that we all share but which has nothing to do with our identities” — this isn’t human nature, but “citizenship”. Undermining the “universal democratic we on which solidarity can be built,” Lilla complains, liberals have been “unmaking rather than making citizens.” It is necessary to return from “me” to “we,” he insists.

Lilla’s attachment to radical we-liberalism becomes perhaps the clearest in his attack on liberals’ “legalistic” approach to politics. “Most foolishly,” he writes, liberals grew “increasingly reliant on the courts to circumvent the legislative process when it failed to deliver what they wanted.” Rather than “building consensus,” they preferred presenting their case as “a matter of absolute legal right.” Working by this method, instead of convincing the American “demos,” the only people liberals had to convince are the “judges” assigned to their case.

This rebuttal of ACLU and its sister organizations is, in fact, covert anti-constitutionalism. Lilla here de facto subscribes to a voluntarist interpretation of liberalism — preferring the will of the American people, the “we,” to the prescribed principles that were supposed to bind it. In this light, when this book speaks of American “national pride,” it prefers the demos collectively respecting the national anthem to the United States Constitution. “We,” Lilla writes at some point, “is where everything begins.”

This latter proposition is the book’s main premise, and it is also its main liability. Because liberalism has replaced universal metaphysics by a non-universal ‘we’, the distinction between identity- and patriotic liberalism has actually become not so sharp. This distinction wasn’t watertight already in Rorty’s time; but it has been finally reduced ad absurdum by the rise of Trump in American politics. If we are to learn anything at all from this absurd, it is that patriotic liberalism is but a species of identity liberalism: not of women, blacks, L.G.B.T or Muslims, but of those who can start the political debate by asserting “we Americans.”

In other words, ‘we’ is not where everything begins; it is where everything ends. Political progress in America has always been achieved through the struggle — even the civil war — over who would utter ‘we’ successfully. And the struggle goes on: insofar as it only has the current “we Americans” to fall back on as anchor, nothing in this patriotic locution could distinguish a progressive sounding “Achieving Our Country” from the reactionary “Make America Great Again.”

Lilla seems to be at least bothered by these complications, for he repeatedly modifies the words ‘citizen’ and ‘we’ by the adjective ‘universal’; and, in two irritated footnotes, he dismisses the question of who counts as a citizen as a “sign of how polluted our political discourse has become.” Polluted or not, these are the questions haunting the book. The reference of the word ‘we’ is never universal; patriotic politics is not cosmopolitan politics. By the same token, ‘universal citizenship’ is a contradiction in terms. In short, liberalism is not humanism: having dissociated truth from politics, it can lay no claim to universality. If Lilla’s promotion of a universal patriotic we is not a noble lie, then it is an attempt to enjoy the fruits of metaphysics without assuming the appropriate responsibilities.

At times, Lilla’s rhetoric suggests that he would be open to embrace his metaphysical commitments. For example, when he writes that politics is not about “speaking truth to power” but about “seizing power to defend the truth.” But if this claim is meant seriously, it contradicts everything that the book is about, suggesting that ‘we’ should be dispensed with in favor of some prior truth — presumably, some metaphysical conception of the good, or a universalist conception of natural right. In that case, the book prescribes not a return from “me” to “we”, as Lilla prefers to present it; but from “we” to truth – it thereby takes a step into a horizon beyond liberalism. The once and future liberal may not be much of a liberal after all.

An Afterword about the Book’s Dedication:

Lilla’s attacks on “legalism” and leftist “narcissist” pseudo-politics would have a familiar ring to Israeli readers from the writings of the publicist Gadi Taub. Just three weeks ago, Taub attacked in Haaretz the “legalization” of Israeli democracy, by which he meant human rights activists’ tendency to “transfer political questions” to the “legal realm.” In another recent Haaretz op-ed, Taub mocked Israeli leftists for conducting politics as a form of personal “therapy,” preferring their own self-expression to genuine political activity. The similarities to Lilla’s position are not coincidental: The Once and Future Liberal is dedicated not only to Lilla’s wife and daughter, but also to his friend Gadi Taub, who “years ago” urged him to “write a book something like this one.” It would be interesting to see whether Lilla thinks that his position can be translated from the American context to the Israeli one. Taub has certainly undertaken such a translation job, but this cannot be done in good faith. Whereas Lilla’s position consists in stressing the neutrality of citizenship as the essence of liberal politics – and as the means to overcome narcissist identity liberalism – Taub’s Zionism consists in denying just that. Unlike the U.S., Israel does not purport to be a neutral liberal democracy: it is a Jewish state, of the Jewish People—not an Israeli one belonging to its citizens as such. If Lilla insisted on his neutral citizenship principle in the Israeli context, an honest Taub would actually mock him as a post-Zionist, narcissist leftist. Instead, holding fast to Zionism’s official identity politics, Taub pretends to apply Lilla’s civic liberalism in attacking the Israeli left.