In the 10 years since its release, much has been made of The National’s Boxer as a “grower” album. This record — the fourth offering by the band — elevated the group to rock-stardom while at the same time serving as a subtle, poignant bridge from Alligator (2005) to High Violet (2010).

This term — “grower” — is both meant and taken as a compliment. The term itself is used to describe an album that needs multiple listens before it can be fully appreciated. In his initial review of Boxer, Stephen M. Deusner referenced the word as a sign of the “good will” of fans of the band. Recently, Ryan Leas also lauded Boxer as a “grower,” and added such phrases as “This was the beginning of the National…” and “This was the start of the National…”

All this is well and good and accurate. But the danger of viewing Boxer as important to the band’s development is that we will stop listening to it. It will become a prelude to the main event, and nothing more. If we call Boxer a “grower” and leave it at that, then, after a few initial listens, we assume that we know its tricks, its subtleties, its delights – and we move on to High Violet, Trouble Will Find Me, and, soon enough, Sleep Well Beast. It’s rather like someone who skims T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” and says, “Well, yes, that’s quite a nice poem. I can see how he could then write ‘The Waste Land.’” Such a person would not be wrong, of course. But they would be missing the point of “Prufrock” (and, probably, “The Waste Land”).

So what is the point of “Prufrock”? And why should you re-listen to Boxer when Father John Misty and Future seem intent on releasing new material every two weeks? Why, with such a plethora of options before you, should you go backwards and listen to the 2007 musings of M. Berninger & Co.?

The answer lies not with importance or critical-to-survival-in-the-Trump-age or even unadulterated originality. No, the answer arrives via a simple Emily Dickinson quote: “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off,” she once wrote in a letter, “I know that is poetry.”

I know that indie-rock is not poetry, per se. But substitute any of your loves/passions/hobbies/interests for that final word, and see if the definition doesn’t hold.

Boxer has, time and again over the past 10 years, made me feel, physically, as if the top of my head had been blown off. This is not hyperbole. It is exceptional art doing what exceptional art does.

¤

Based in Brooklyn, The National is an indie-rock band best known for its lead singer, Matt Berninger, whose deep voice and wry, brooding lyrics trod steadily along over the dueling Dessner bros.’ guitar play, which is in turn driven by drummer Bryan Devendorf, whose drums do not provide a baseline so much as the occasional kick in the pants. Since Boxer’s release, The National has grown steadily from a niche indie-rock band to a now-famous and aging-appropriately indie-rock band of the type that sells out old Masonic temples. For those of you unfamiliar with this particular genre of music, just take my word for it that their rise in popularity has been tremendous.

Since we’ve already gone to the trouble of summoning J. A. Prufrock from his primordial abyss, let’s keep him around, as he may help us pin down just what that as-yet-undisclosed quality in Boxer is that blows the tops of our heads off.

For anyone familiar with “Prufrock,” there should be a moment of tonal recognition between Berninger’s self-conscious urban malaise and Prufrock’s “overwhelming question.” For those unfamiliar with Eliot’s poem, allow me to recommend it as a prime evocation of that certain quality of day-to-day social anxiety that can paralyze your average Joe/Alfred/Prufrock.

A few comparisons are in order.

First, from Eliot: “Should I, after tea and cakes and ices, / Have the strength to force the moment to its crisis?” Tell me that these lines, when paired with Devendorf’s off-kilter drumming or Sufjan Stevens’s elegant piano, could not have belonged on Boxer. If those lines sounded familiar, consider now these lyrics from “Racing Like a Pro,” the 10th song on Boxer: “Sometimes you get up and bake a cake or something, / Sometimes you stay in bed. / Sometimes you go, ‘La Dee Da Dee Da Dee Da Da, / Until your eyes roll back into your head.”

This is not a moment of pure coincidence regarding certain baked goods. It’s a real attempt by two separate men, writing in two distinct times, to grapple with the terror of growing up in a 20th century Western upper-class milieu.

Nor is this the only time such similarities occur. When Berninger’s speaker passes his friends in the dark “under silvery, silvery Citibank lights,” this harrowing nighttime scene shares an emotional register with Prufrock’s ambivalent desire to go into “certain half-deserted streets, / The muttering retreats / Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels…” Or, again, who could not imagine Prufrock lamenting, “Ada, I can hear the sound of your laugh through the wall.”

Boxer is not the same as Prufrock,” and Matt Berninger is not the next T.S. Eliot. My hope is to provide you with some context for Berninger’s wry, solemn lyrics, as well as those muttering drumbeats that underlie the entire album. Put plainly, what “Prufrock” and Boxer share is a concern with how to live amidst the anxiety, pain, and ennui of daily adult life. “Prufrock” does not provide an answer to that problem; whether Boxer does needs further examination.

¤

Another reason Boxer has become associated with the term “grower” is the radical popularity of “Fake Empire,” the opening cut of the album. Famously, an instrumental version of the song was featured in one of Barack Obama’s campaign videos during the 2008 election cycle. The piano’s polyrhythmic lilt is at once comforting and disconcerting, and has made the song one of the band’s most recognizable to date. Indeed, perhaps the most notable strength of “Fake Empire” is that, with all of its hype and ubiquity, the song refuses to grow worn out, stale, tired. In other words, “Fake Empire” has been overplayed, and yet we continue to listen to it.

Few songs have this quality. And while I’m certain there are many reasons for the song’s unfailing quality, I’ll offer just one: “Fake Empire” offers itself as a portrait of a specific man, in a specific time and place, with whom millions of listeners have, for the past 10 years, continued to identify.

This man is not Matt Berninger. Certainly, he is made up of Berninger’s steady, sing-speak lyrics — but that is only half of what we see. The other half is the music undulating underneath the lyrics. “Fake Empire” offers a person in crisis. We hear the words he’s saying, but the music — the unsteady piano, those troubled drum patterns — suggest that the words are not the whole story. There is chaos beneath the calm surface, and we must make a choice. Will we listen to the words the man speaks or the troubled noises his subconscious makes?

¤

Though Boxer is a solemn album, it is not morose. Again, from a different angle: Boxer is dark, but it is not menacing, dangerous, or concerned with the occult. These distinctions can be tricky, so here is C.S. Lewis, in his “Preface to Paradise Lost,” explaining the difference between the Middle English word solempne and our word solemn:

Like solemn it [solempne] implies the opposite of what is familiar, free and easy, or ordinary. But unlike solemn it does not suggest gloom, oppression, or austerity […] A great mass by Mozart or Beethoven is as much a solemnity in its hilarious gloria as in its poignant crucifixus est. Feasts are, in this sense, more solemn than fasts.

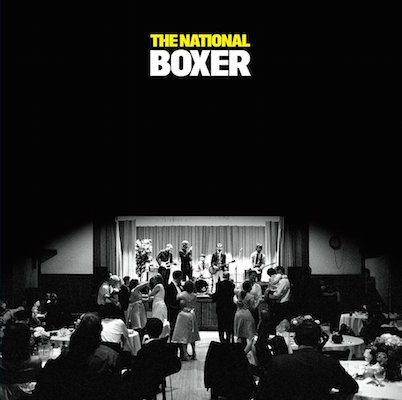

Taken this way, Boxer opens up its delights before us. The stakes are high, yes, but the presence of solemnity does not damn the album to defeatism. As with the photo on the album’s cover, Boxer asserts that a dark scene may be just that –— but it may also be as harmless as the dimly-lit dance floor of a wedding reception.

This solemnity is the real magic of Boxer. Throughout the 12 songs, it offers scene after scene of “another un-innocent elegant fall into the un-magnificent lives of adults” (“Mistaken for Strangers.”) And while, on the surface, this “fall” might seem Miltonic in its significance, Boxer demands that we listen more thoughtfully than that. And when we do, our second listen finds that, taken one at a time, these descriptors — “un-innocent”; “elegant”; “un-magnificent” — are not so terrifying after all. For in Boxer no series of days, nights, or weeks is ever simply good or bad. Boxer resists the urge to label with such simplicity. Instead, it asserts that our lives may be “un-innocent” (indeed, they will be), but they can also be “elegant.”

This crucial ambivalence is what makes Boxer’s solemnity so critical to the success of the project. You cannot feign solemnity with a wink or scathing satire. It requires — almost by definition — sincerity. Such an approach, especially in popular, indie-rock music, is under extreme attack, and has been for the last decade. Indeed, a brief look around the genre finds artists like Father John Misty and Arcade Fire, both of whom offer such postmodern, ironic offerings as Father John Misty’s recent album Pure Comedy and Arcade Fire’s mock-annotated, self-referential music video for “Creature Comfort.”

Listening to Boxer today refutes the ironic approach. It may sustain for the moment, but, after a decade, the jokes will wear thin. One cannot help but agree with David Foster Wallace that “irony’s gone from liberating to enslaving.” Boxer rejects irony, and offers instead a solemn, sincere attempt to respond to the problems it encounters.

Certainly, there are moments of cool dispassion. But these are far overshadowed by instances of such un-cool sincerity that our initial impulse may be to turn away in cheek-reddening embarrassment. “Whatever went away, I’ll get it over now / I’ll get money, I’ll get funny again,” promises Berninger on “Start A War.” The appeal is heartbreaking in its desperation. Similarly, on “Slow Show,” Berninger admits, “You know I dreamed about you / For 29 years before I saw you. / I missed you for 29 years.” If these lyrics come under fire for their sincerity, perhaps such criticism says more about our current moment’s fear of exposure — of being honest about our own insecurities — than it does about Berninger’s lyricism.

And so we arrive at Boxer’s final gift. On this record, the members of The National walk squarely into the thicket of postmodern, adult worry — and, from the midst of that mess of thorns and “Citibank lights,” they relay to us what they have found in precise, unadorned songs. What they find is not always pretty, but it has, for the last 10 years, taken the top of my head off.