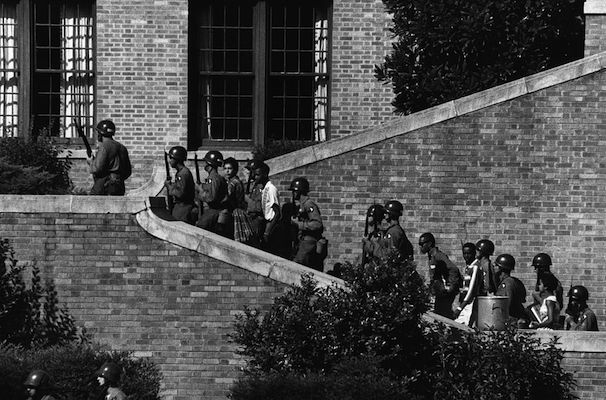

The U.S. recently celebrated the 60th anniversary of the Little Rock Arkansas Central High School’s integration. The commemoration included reflections on the turbulence of the civil rights era and memorialized how Little Rock became a flashpoint in the struggle for racial equality. While many acknowledge progress in race relations, data suggests that decades after Brown v. Board of Education, public schools are still largely segregated.

Twenty years ago I performed a full-length ballet about the Little Rock Nine in which I played a role based on a white woman snarling at Elizabeth Eckford in a famous Francis Miller photograph. I was a young dancer and this opportunity provided me with my first opportunity to consider whiteness, privilege, access, and racism within a creative process.

It may not be intuitive to connect dance with the pursuit of racial justice, but given the continued disparity in economic opportunities between white and black people in America as well as perceptions of increased racial tension across the country, artists should consider their roles in moving the dialogue forward. Many artists do this through their work and activism, but too often we rely on the self-congratulatory attitude that art has a long-standing tradition of embracing pluralistic orientations and providing a platform for marginalized voices as represented by figures who continue to challenge socially constructed boundaries of gender, sexuality, ability, class, and race.

In recent years there has been increased conversation about systemic racism in concert dance and the general marginalization of black dancers. Nowhere has this conversation sparked more debate than in the ballet world. Ballet is a 15th century art form that emerged from the courts of Western Europe and was codified by Louis XIV in France. Choreographic innovation and stylistic changes marked the emergence of neoclassical ballet in the modern era, but for the most part, ballet training and classical performances have remained nearly unchanged for 400 years.

Ballet is a spectacle performed in opulent theaters with full live orchestras. Set designs are grand and costuming is traditionally rich. A handmade tutu, itself a piece of art, can be worth thousands of dollars. Ballet is also historically and stubbornly white. Many people love ballet because of the traditions, but the reality is that the traditions often keep black artists on the margins, signaling racism and white supremacist ideologies embedded within the art form. It’s worthwhile to note that two years after American Ballet Theater’s Misty Copeland was the first black woman in the company’s history promoted to principal, a scan of elite American ballet company rosters continues to show a largely racially homogenous landscape.

It is useful to apply the first tenet of a Critical Race Theory framework to an analysis of ballet, using education as a metaphor, because this tenet emphasizes the normalization of racism. The microaggressions born of that normalization persist even when overt displays of racism are no longer considered acceptable. Why, for example do we continue to costume dancers of color in “American” or “European” pink tights? In ballet, a prevailing assumption that a black body is physiologically unsuited to ballet fits almost exactly with long-standing racist principles that continue to impact black students in education; namely, that black students are intellectually inferior. The expenses associated with rigorous dance training and lack of black dancer representation in elite ballet companies also matches the experience of many black students who struggle to afford a quality education and don’t see enough people of color represented in leadership positions.

Some professional ballet programs are attempting to increase racial diversity and to amplify the voices of black dancers. American Ballet Theatre’s Project Plie is an initiative launched in 2013 to “diversify America’s ballet companies” by training and supporting ballet students from underserved communities, and Gaynor Minden, a respected pointe shoe maker, recently launched a line of shoes to match black dancers’ skin tones.

These markers of progress also demand critique, caution, and reflection. There is danger in believing that the past 60 years have seen a transformation of racial attitudes, in that years from now the professional ballet landscape could end up looking like the Arkansas public school system does today. If we consider pioneering law professor Derrick Bell’s concept of racial realism, even when arts program leaders state an explicit desire to pursue social justice, they are operating within such a fundamentally flawed system that genuine progress towards equity may be as fantastical as Act II of Swan Lake.