I rejoiced last June when the Librarian of Congress, Carla Hayden, announced her appointment of Joy Harjo as our new Poet Laureate. In a recent review of Jennifer Reeser’s Indigenous, I had stated that “[t]he enduring indigenous poet of the early 21st century is almost certain to be Joy Harjo.”

My pleasure, however, did not last long. When I read the full press release, I saw that it referred to Harjo as “the first Native American poet to serve in that position.” I became anxiously confused because, in my review of the Reeser book, I had also written:

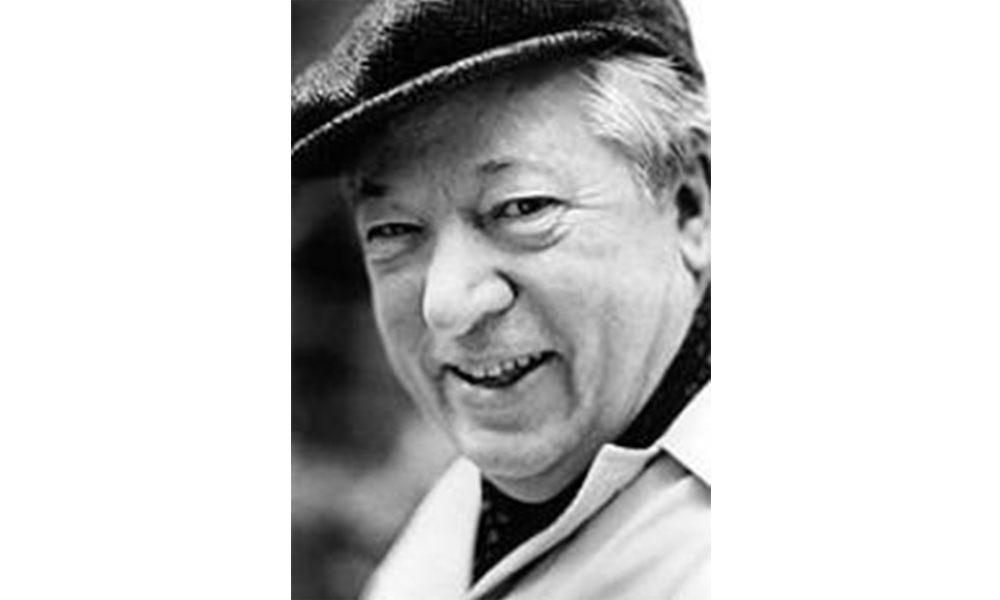

The first widely celebrated indigenous American poet was William Jay Smith (1918-2015), a brilliant and charming Rhodes Scholar who served as Poet Laureate of the United States from 1968-1970. Smith primarily wrote and translated highly polished and often very funny formal verse for both adults and children.

Had I made a mistake? I calmed down when I checked two reliable sources known for their fact checking, the Poetry Foundation and The New York Times, which both identified Smith as Native American. I became even calmer when I discovered, with some help from friends at Eratosphere, an online poetry workshop and discussion group, that the Library of Congress had itself identified Smith as “of European and Choctaw ancestry.”

I felt an obligation to notify the Library promptly, which I did. The first contact person had never heard of Smith and transferred me to another person who had not heard of Smith. That person took my name and number, but did not call back.

I raised the inconsistency with some vigor on Twitter, and my tweet received some attention. As the result of an inquiry by the PBS NewsHour to the Library, I learned that the Library did not intend to correct its press release. I then followed up with the Library’s communications office, which summarily stated that it did not consider Smith to be a Native American and asked me to send future questions in writing.

My promptly submitted questions were:

1) Has the Library of Congress decided that William Jay Smith is not a Native American? If not, will the Harjo press release be corrected?

2) If so, what was the standard for this decision, what was the evidence that supported it, and who made the decision?

3) If so, was this decision made before the Harjo announcement or afterwards?

4) Are you aware that for 15 years the Library of Congress website has described Smith as being “of European and Choctaw ancestry”?

The following Tuesday I received a response from the Library’s acting head of communications — a response that ignored three of my questions and responded only partially to the first question in this fashion:

William Jay Smith was a former Consultant in Poetry at the library from 1968-1970. In his memoir he refers to the possibility he had some Choctaw ancestry. Based on our research, however, he does not appear to have been an enrolled member of a Choctaw nation.

This description of Smith’s memoir, Army Brat (1980), is grossly misleading. In it, he does far more than refer to “the possibility that he had some Choctaw ancestry.” He specifically claims to be a descendant of a head of the Choctaw Nation, Chief Moshulatubbee, who signed treaties with the United States in 1816, 1820, and 1830. Indeed, he lays out in detail his reasons for believing that his great-great-grandmother, Rebecca Williams, was the daughter of Moshulatubbee.

The Library’s statement referring to tribal membership also conveniently omitted the fact that Smith politely, but forcefully, argued that the Department of the Interior committed miscarriages of justice a century ago by denying tribal membership to at least two family members. The Interior Department of the early 20th century saw no need to expand its count of Native Americans, and that attitude tainted their adjudications. In one case, Smith asserted, Interior denied a relative’s claim by relying on an alternate spelling of Moshulatubbee to conclude that the chief never existed. In the other case he argued that Interior denied a relative’s claim based on a visual inspection of the physical features of the claimant.

Tribal membership as the standard for ethnicity is a recent phenomenon, and was not the standard during Smith’s lifetime. The Library of Congress cavalierly disrespected the memory of its former Poet Laureate (the “Consultant in Poetry” title was upgraded to “Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry” in 1986) by retroactively imposing that requirement.

Almost surely the communications department believed that it could tough its way out of the mess it created based on the fact that so many Americans believe — falsely, but in good faith — that they have Native American heritage. Such issues are often resolvable, though, and I decided to try to resolve the question of William Jay Smith’s heritage by hiring an expert in Native American genealogy, Dr. William T. Cross.

Dr. Cross’s research confirmed that everything William Jay Smith claimed about his Choctaw heritage was correct. Rebecca Moshulatubbee King was the oldest daughter of Chief Moshulatubbee and married Samuel Jake Williams. One of their seven daughters, Catherine Permilia Williams, married Samuel Roswell Campster in 1850, and then gave birth to George Washington Campster in 1863. In 1913 George Washington Campster’s daughter, Georgia Ella Campster, married William Jay Smith Sr., the father of our Poet Laureate.

Standards for tribal nation membership vary, but the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma simply requires lineal descent for membership, so William Jay Smith would have been fully eligible for membership if he had applied. There can be no doubt about Smith’s good faith in claiming that he was part Choctaw; at that time the benefits of such a claim would not offset the prejudices that it would generate. Nonetheless, the future Poet Laureate enthusiastically embraced his Choctaw heritage at an early age; it filtered into his poetry at least as early as the 1950s, when in “A Trip Across America” he repeated these lines:

Riding the powerful polished rails

Over abandoned Indian trails…

More than four decades later, he would do much more.

Perhaps Smith’s most important contribution to American poetry and society was The Cherokee Lottery: A Sequence of Poems (2000), a book which Harold Bloom called “his masterwork; taut, harrowing, eloquent, and profoundly memorable.” It is the book that brought the epic tragedy of “The Trail of Tears” from shameful obscurity into our national consciousness, a contribution for which Smith has never received adequate recognition.

Now as they march us

to the west,

we abandon our dead

along the way —

with no red pole,

no dark grape vine

to mark their graves —

and only our tear

to seal our trail.

Proper recognition for William Jay Smith, a decent and talented man who was a direct descendant of a historically significant Choctaw chief, should be the outcome of this sad episode at the Library of Congress. Carla Hayden should ask Joy Harjo for help in developing a conference to examine and celebrate William Jay Smith’s legacy — his children’s poetry, his “light” and “serious” verse, his translations from many languages, as well as the many influences of The Cherokee Lottery.

All of the proceedings of that conference should be added to the Library’s website so that the public can learn about the great poet that the Library of Congress forgot.

A.M. Juster (@amjuster on Twitter) is a poet, translator, and critic whose work has appeared in Poetry, The Hudson Review, The Paris Review, Rattle, and many other journals. His tenth book, Wonder and Wrath, will be published in early 2021 by Paul Dry Books.

Photo credit: Robert Turney.